The Struggle in Defense of Baikal: the Shift of Values and Disposition of Forces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

Problems of Reforming of Housing and Communal Services of Cities of Irkutsk Region in the 1990S

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 4 (2016 9) 923-939 ~ ~ ~ УДК 908.647.63.3 Problems of Reforming of Housing and Communal Services of Cities of Irkutsk Region in the 1990s Tatiana P. Urozhaeva* Irkutsk State University 1 Karl Marks Str., Irkutsk, 664003, Russia Received 24.10.2015, received in revised form 14.01.2016, accepted 24.03.2016 The aim of the article is the analysis of main trends and implications reforms in housing and communal services of cities of Irkutsk region in the first post-Soviet decade. The subject of research is the reform of housing and communal services, which provided a radical change from the planning and administrative methods of regulation of the housing sector to market mechanisms. The study tested hypothesized that the attempts of state authorities to entrust the accumulated problems in the industry on municipalities in isolation from the reform of public utilities, domestic service etc., and, most importantly, empowerment of local government in the pricing and quality of public services, and are unable to lead to the desired results. In the course of writing were used research methods of social phenomena in historical perspective, analyzes a variety of information sources and literature. The benefits of this study in studied publications in local, regional and central periodicals, monographs and articles, as well as statistical materials. The article concludes that the formation of the mechanisms of the sphere housing and communal services occurred in the conditions of hard budget constraints, there was a constant search of balance in the cost of housing between the population and the budget. -

Waterbirds of Lake Baikal, Eastern Siberia, Russia

FORKTAIL 25 (2009): 13–70 Waterbirds of Lake Baikal, eastern Siberia, Russia JIŘÍ MLÍKOVSKÝ Lake Baikal lies in eastern Siberia, Russia. Due to its huge size, its waterbird fauna is still insufficiently known in spite of a long history of relevant research and the efforts of local and visiting ornithologists and birdwatchers. Overall, 137 waterbird species have been recorded at Lake Baikal since 1800, with records of five further species considered not acceptable, and one species recorded only prior to 1800. Only 50 species currently breed at Lake Baikal, while another 11 species bred there in the past or were recorded as occasional breeders. Only three species of conservation importance (all Near Threatened) currently breed or regularly migrate at Lake Baikal: Asian Dowitcher Limnodromus semipalmatus, Black-tailed Godwit Limosa limosa and Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata. INTRODUCTION In the course of past centuries water levels in LB fluctuated considerably (Galaziy 1967, 1972), but the Lake Baikal (hereafter ‘LB’) is the largest lake in Siberia effects on the local avifauna have not been documented. and one of the largest in the world. Avifaunal lists of the Since the 1950s, the water level in LB has been regulated broader LB area have been published by Gagina (1958c, by the Irkutsk Dam. The resulting seasonal fluctuations 1960b,c, 1961, 1962b, 1965, 1968, 1988), Dorzhiyev of water levels significantly influence the distribution and (1990), Bold et al. (1991), Dorzhiyev and Yelayev (1999) breeding success of waterbirds (Skryabin 1965, 1967a, and Popov (2004b), but the waterbird fauna has not 1995b, Skryabin and Tolchin 1975, Lipin et al. -

Final Report

SIBERIA SAR Imaging for Boreal Ecology and Radar Interferometry Applications EC ENVIRONMENT AND CLIMATE PROGRAMM THEME 3: SPACE TECHNIQUES APPLIED TO ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING AREA 3.3: CENTER FOR EARTH OBSERVATION Final Report SIBERIA SAR IMAGING FOR BOREAL ECOLOGY AND RADAR INTERFEROMETRY APPLICATIONS List of Partners: Country DE FR UK FI SE AT RU CH Teams 2 1 3 1 1 1 3 1 June 2001 1 The responsibility for the contents of this document rests with the Friedrich-Schiller- University (FSU) Jena, Germany. Copyright rests with FSU and the individual consortium partners. All representation or reproduction done without the consent of FSU is illegal, with the exception of the consortium partners, the Customers, and the European Commission. This report describes the work done during the full period of the SIBERIA project (August 1998 to December 2000). SIBERIA is financed through the 4th Framework Programme of the European Commission, Environment and Climate, Area 3.3: Centre for Earth Observations. Contract No.: ENV4-CT97-0743-SIBERIA Project Co-ordination: Remote Sensing Unit, Institute for Geography, Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena, Germany. Authors: J. Baker, H. Balzter, M. Davidson, L. Eriksson, D. Gaveau, M. Gluck, A. Holz, A. Luckman, U. Marschalk, I. McCallum, S. Nilsson, A. Öskog, S. Quegan, Y. Rauste, A. Roth, C. Schmullius, A. Shvidenko, K. Tansey, T. Le Toan, J. Vietmeier, W. Wagner, U. Wegmüller, A. Wiesmann, J. J. Yu. Edited by C. Schmullius, FSU Jena. 2 Table of contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................................... 7 1 OBJECTIVES OF THE PROJECT............................................................................................................ 8 1.1 THE RUSSIAN FOREST SECTOR AND THE NEED FOR ACCURATE MAPS ................................................... -

The Transportation of Soviet Energy Resources

FINAL REPORT T O NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE : The Transportation of Soviet Energy Resources AUTHOR : Matthew J . Sagers and Milford Green CONTRACTOR : Weber State College . Sagers and Milford B . Green PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : Matthew J COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 628-2 DATE : January 198 5 The work leading to this report was supported in whole or in part from funds provided by the National Council for Sovie t and East European Researoh . EXECUTIV E SUMMARY Soviet energy resources are the largest in the world, ye t energy problems have not bypassed the USSR . A major aspect o f current Soviet energy difficulties lies in the problem of tran- sporting energy . This is because of the USSR's large size (one - sixth of the world's land surface) and the spatial disparit y between energy resources and demand . A key dichotomy exist s between the industrialized and densely settled " Europea n " portio n of the USSR and the thinly populated, but energy-rich, easter n portion (Siberia) . Most of the demand for energy originates i n the European portion, as it contains 5-80% of the Soviet popula- tion, industry, and social infrastructure . In contrast, th e Siberian portion contains only about 10% of the Soviet popula- tion, but almost 90% of the country's energy resources . This study attempts to analyze the transportation of Sovie t energy resources . The purpose is to determine the general pat - tern of movement for each of the main forme of energy (gas, crud e petroleum, refined products, coal, and electricity), to identif y constraints in the transportation system that inhibit efficien t flows, and to evaluate the prospects for future developments , based upon this analysis of the system . -

Annual Report 2009 Oao Irkutskenergo

ANNUAL REPORT 2009OAO IRKUTSKENERGO 11 ANNUAL REPORT 2009 OAO IRKUTSKENERGO Irkutsk г. Иркутск 2 ABBreViations ARIS Business process modelling methodology and software MIRBIS Moscow International Higher Business School ASKIB Automated Treasury Based Budget Management and Control System LV Low Voltage BHPP Bratskaya Hydroelectric Power Plant UDCC of Siberia United Dispatch Control Centre BM Balancing Market OREM Wholesale Electric power Market GDP Gross Domestic Product IPSS Incorporated Power System of Siberia HV High Voltage MPE Maximum Permissible Emission GS Guaranteeing Supplier MPD Maximum Permissible Discharge GPB OAO Gazprombank D&E Design and Exploration F&L Fuel and lubricants EIP Efficiency improvement programs HPP hydroelectric power plant RC Regulated long-term contracts for electric power BCPC Bilateral contract for power and capacity UDCC United Dispatch Control Centre AR Accounts Receivable DAM Day-ahead market SAC Subsidiaries and affiliated companies NRBC Non-regulated bilateral contract VMI Voluntary medical insurance NRECC Non-regulated electric power and capacity contracts EBWD Eniseysk Basin Water Directorate ANNUAL REPORT 2009OAO IRKUTSKENERGO 33 MV Medium voltage HUC Housing and utility companies SO UES System Operator of the Unified Energy System ASW ash and slag waste PIS Performance Indicator System EB Executive Board ES Enterprise Standard CSS Commodity stocks and supplies IESK OOO Irkutsk Grid Company CPOP Comprehensive production optimization program CCN Corporate computer network TPP Thermal Power Plant CPS -

BR IFIC N° 2663 Index/Indice

BR IFIC N° 2663 Index/Indice International Frequency Information Circular (Terrestrial Services) ITU - Radiocommunication Bureau Circular Internacional de Información sobre Frecuencias (Servicios Terrenales) UIT - Oficina de Radiocomunicaciones Circulaire Internationale d'Information sur les Fréquences (Services de Terre) UIT - Bureau des Radiocommunications Part 1 / Partie 1 / Parte 1 Date/Fecha 23.02.2010 Description of Columns Description des colonnes Descripción de columnas No. Sequential number Numéro séquenciel Número sequencial BR Id. BR identification number Numéro d'identification du BR Número de identificación de la BR Adm Notifying Administration Administration notificatrice Administración notificante 1A [MHz] Assigned frequency [MHz] Fréquence assignée [MHz] Frecuencia asignada [MHz] Name of the location of Nom de l'emplacement de Nombre del emplazamiento de 4A/5A transmitting / receiving station la station d'émission / réception estación transmisora / receptora 4B/5B Geographical area Zone géographique Zona geográfica 4C/5C Geographical coordinates Coordonnées géographiques Coordenadas geográficas 6A Class of station Classe de station Clase de estación Purpose of the notification: Objet de la notification: Propósito de la notificación: Intent ADD-addition MOD-modify ADD-ajouter MOD-modifier ADD-añadir MOD-modificar SUP-suppress W/D-withdraw SUP-supprimer W/D-retirer SUP-suprimir W/D-retirar No. BR Id Adm 1A [MHz] 4A/5A 4B/5B 4C/5C 6A Part Intent 1 109116729 ARG 7254.0000 SAN MIGUEL ARG 57W35'23'' 27S59'47'' FX 1 ADD 2 110005716 -

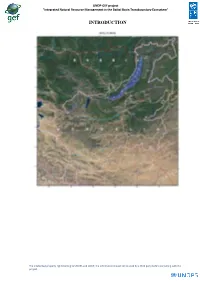

Introduction

UNDP-GEF project "Integrated Natural Resource Management in the Baikal Basin Transboundary Ecosystem" INTRODUCTION The intellectual property rights belong to UNOPS and UNDP, the information should not be used by a third party before consulting with the project. UNDP-GEF project "Integrated Natural Resource Management in the Baikal Basin Transboundary Ecosystem" The intellectual property rights belong to UNOPS and UNDP, the information should not be used by a third party before consulting with the project. UNDP-GEF project "Integrated Natural Resource Management in the Baikal Basin Transboundary Ecosystem" The intellectual property rights belong to UNOPS and UNDP, the information should not be used by a third party before consulting with the project. UNDP-GEF project "Integrated Natural Resource Management in the Baikal Basin Transboundary Ecosystem" The intellectual property rights belong to UNOPS and UNDP, the information should not be used by a third party before consulting with the project. UNDP-GEF project "Integrated Natural Resource Management in the Baikal Basin Transboundary Ecosystem" The intellectual property rights belong to UNOPS and UNDP, the information should not be used by a third party before consulting with the project. UNDP-GEF project "Integrated Natural Resource Management in the Baikal Basin Transboundary Ecosystem" NATURAL CONDITIONS OF FORMATION OF ECOLOGICAL SITUATION INTHELAKEBAIKALBASIN Explanatory notes for the geological map of the Baikal watershed basin Many features inherent in the geological structure of the territory of the watershed basin are due to the fact that the territory lies at the interface between the two main lithospheric plates of East Siberia, namely the old Siberian platform, and the younger Central-Asian mobile belt. -

Annual Report of SOGAZ Insurance Group

Annual Report of SOGAZ Insurance Group Annual Report of SOGAZ Insurance Group 2011 CONTENTS > A WORD FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ...................5 > A WORD FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE MANAGEMENT BOARD ....................6 01 > ABOUT SOGAZ INSURANCE GROUP ..............................................................8 Management .................................................................................................................................... 12 Position in the Insurance Market ................................................................................13 • Russian Insurance Market: 2011 Results .................................................................... 13 • Group Operation Results ......................................................................................... 16 02 > GROUP’S ACTIVITIES IN 2011 ........................................................................18 Insurance ...................................................................................................................20 • Property and Liability Insurance .................................................................................20 • Special Risk Insurance .............................................................................................24 • Personal Insurance .................................................................................................26 Sales Channel Development ....................................................................................................... 31 -

World Bank Document

Report No. 25893-RU Russian Federation E-Learning Policy to Transform Russian Schools Public Disclosure Authorized April 29, 2003 Human Development Sector Unit Europe and Central Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EOUIVALENT (as of March 30,2003) Currency Unit = Ruble RUR US$1 = RUR 30.00 FISCAL YEAR January 1- December 31 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS E-Education Federal Program "Development of the Common Education Information Space for 2001-2006" E-Russia Federal Program "Electronic Russia for 2002-2010" FIE Federation of Internet Education HE Higher Education ICT(E) Information and Computer Technology (Education) IV(E) Initial Vocational (Education) MOE Ministry of Education NTF National Training Foundation OSI Open Society Institute PISA OECD Program for International Student Assessment TIMSS Third International Mathematics and Science Study Vice President: Johannes F. Linn Country Director: Julian F. Schweitzer Sector Director: Annette Dixon Sector Manager: Maureen McLaughlin Task Team Leader: Isak Froumin ii PREFACE Russia, in common with many other countries, is investing a significant part of its education budget in information and communication technologies (ICT) equipment for general secondary schools and initial vocational education. While international experience demonstrates that such initiatives may deliver significant educational and social benefits, investment in computer hardware raises a number of issues related to the purpose and projected outcomes of the use of ICT in schools. The goal of this report, which was prepared at the request of the Ministry of Education, is to look at the present state of affairs in the use of ICT in education and to propose and discuss possible policy options open to the Government in its continuing effort to orient the education system towards the global knowledge economy. -

BR IFIC N° 2653 Index/Indice

BR IFIC N° 2653 Index/Indice International Frequency Information Circular (Terrestrial Services) ITU - Radiocommunication Bureau Circular Internacional de Información sobre Frecuencias (Servicios Terrenales) UIT - Oficina de Radiocomunicaciones Circulaire Internationale d'Information sur les Fréquences (Services de Terre) UIT - Bureau des Radiocommunications Part 1 / Partie 1 / Parte 1 Date/Fecha 22.09.2009 Description of Columns Description des colonnes Descripción de columnas No. Sequential number Numéro séquenciel Número sequencial BR Id. BR identification number Numéro d'identification du BR Número de identificación de la BR Adm Notifying Administration Administration notificatrice Administración notificante 1A [MHz] Assigned frequency [MHz] Fréquence assignée [MHz] Frecuencia asignada [MHz] Name of the location of Nom de l'emplacement de Nombre del emplazamiento de 4A/5A transmitting / receiving station la station d'émission / réception estación transmisora / receptora 4B/5B Geographical area Zone géographique Zona geográfica 4C/5C Geographical coordinates Coordonnées géographiques Coordenadas geográficas 6A Class of station Classe de station Clase de estación Purpose of the notification: Objet de la notification: Propósito de la notificación: Intent ADD-addition MOD-modify ADD-ajouter MOD-modifier ADD-añadir MOD-modificar SUP-suppress W/D-withdraw SUP-supprimer W/D-retirer SUP-suprimir W/D-retirar No. BR Id Adm 1A [MHz] 4A/5A 4B/5B 4C/5C 6A Part Intent 1 109072175 ARG 408.7375 CHAJARI ARG 58W01'13'' 30S45'37'' FB 1 ADD 2 109072127 -

The Struggle in Defense of Baikal: the Shift of Values and Disposition of Forces

IRSR INTERNATIONAL REVIEW of SOCIAL RESEARCH Volume 1, Issue 3, October 2011, 33-51 International Review of Social Research The Struggle in Defense of Baikal: The Shift of Values and Disposition of Forces Oleg YANITSKY• Institute of Sociology, Russian Academy of Science Abstract: The paper is aimed at the analysis of evolution of values and disposition of forces involved in the long-term international conflict around the closure of the pulp and paper mill (P&PM) and the reconstruction of the company town of Baykalsk, both located near Lake Baikal, the biggest freshwater lake in the world. The conflict’s six phases are: construction and opening of the pulp and paper mill, P&PM (1967-84); the perestroika (1985-90); the collapse of the USSR (1991); the Russian financial crisis (1998); the struggle against the tracing of a transnational oil pipe-line near Baikal shore (2001-06); and the economic crisis (2008). In each phase, the activity of Russian environmentalists is considered under the following aspects: political opportunity structure, main actors, constituency, key values, forms of activity, kind of mobilization and resources for it, and the outcome of the struggle. The paper is focused on the evolution of the relationship between the state and the environmental movement. Keywords: disposition of forces, environmental movement (EM), mobilization, phases of conflict, political opportunity structure (POS), state, values, Russia. The Case occupies about 557,000 square km and contains about 23,000 cubickm What is the lake Baikal? It covers of water, which is about one fifth of 31,500 square km and is 636 km the world’s reserves of fresh surface- long, an average of 48 km wide, 79,4 water and over 80 percent of the fresh km at its widest point.