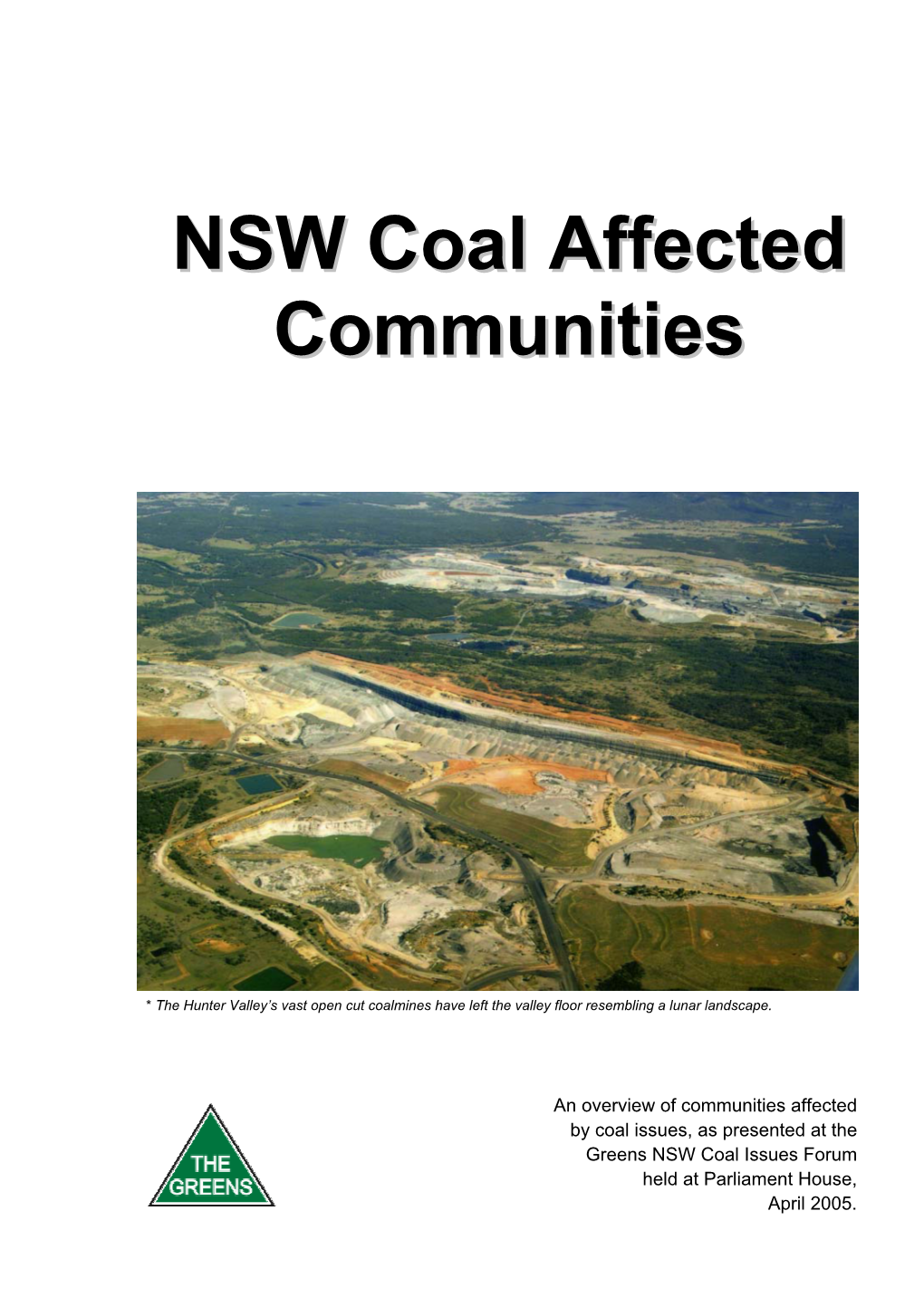

NSW Coal Affected Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Native Vegetation of the Nattai and Bargo Reserves

The Native Vegetation of the Nattai and Bargo Reserves Project funded under the Central Directorate Parks and Wildlife Division Biodiversity Data Priorities Program Conservation Assessment and Data Unit Conservation Programs and Planning Branch, Metropolitan Environmental Protection and Regulation Division Department of Environment and Conservation ACKNOWLEDGMENTS CADU (Central) Manager Special thanks to: Julie Ravallion Nattai NP Area staff for providing general assistance as well as their knowledge of the CADU (Central) Bioregional Data Group area, especially: Raf Pedroza and Adrian Coordinator Johnstone. Daniel Connolly Citation CADU (Central) Flora Project Officer DEC (2004) The Native Vegetation of the Nattai Nathan Kearnes and Bargo Reserves. Unpublished Report. Department of Environment and Conservation, CADU (Central) GIS, Data Management and Hurstville. Database Coordinator This report was funded by the Central Peter Ewin Directorate Parks and Wildlife Division, Biodiversity Survey Priorities Program. Logistics and Survey Planning All photographs are held by DEC. To obtain a Nathan Kearnes copy please contact the Bioregional Data Group Coordinator, DEC Hurstville Field Surveyors David Thomas Cover Photos Teresa James Nathan Kearnes Feature Photo (Daniel Connolly) Daniel Connolly White-striped Freetail-bat (Michael Todd), Rock Peter Ewin Plate-Heath Mallee (DEC) Black Crevice-skink (David O’Connor) Aerial Photo Interpretation Tall Moist Blue Gum Forest (DEC) Ian Roberts (Nattai and Bargo, this report; Rainforest (DEC) Woronora, 2003; Western Sydney, 1999) Short-beaked Echidna (D. O’Connor) Bob Wilson (Warragamba, 2003) Grey Gum (Daniel Connolly) Pintech (Pty Ltd) Red-crowned Toadlet (Dave Hunter) Data Analysis ISBN 07313 6851 7 Nathan Kearnes Daniel Connolly Report Writing and Map Production Nathan Kearnes Daniel Connolly EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report describes the distribution and composition of the native vegetation within and immediately surrounding Nattai National Park, Nattai State Conservation Area and Bargo State Conservation Area. -

Tahmoor Colliery - Longwalls 28 to 30

REPORT: BUILT HERITAGE MANAGEMENT PLAN GLENCORE: Tahmoor Colliery - Longwalls 28 to 30 Management Plan for Potential Impacts to Built Heritage © MSEC MARCH 2014 | REPORT NUMBER: MSEC646-13 | REVISION A AUTHORISATION OF MANAGEMENT PLAN Authorised on behalf of Tahmoor Colliery: Name: Signature: Position: Date: DOCUMENT REGISTER Date Report No. Rev Comments Dec-10 MSEC446-13 A Draft for review Feb-11 MSEC446-13 B Final plan Dec-12 MSEC567-13 A Updated for Longwall 27 to include Tahmoor House Feb-14 MSEC646-13 A Updated for Longwalls 28 to 30 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Management Plan was prepared with the assistance of Tahmoor Colliery, Niche Environment and Heritage, Biosis Research and John Matheson & Associates. References:- Biosis, (2009). Tahmoor Colliery – Longwalls 27-30, Impacts of Subsidence on Cultural Heritage. Biosis Research, May 2009. JMA, (2012). 27 Remembrance Drive, Tahmoor Structural Inspection Report, John Matheson & Associates, Report No. 0194, Rev. 1, July 2012. MSEC, (2009). Tahmoor Colliery Longwalls 27 to 30 - The Prediction of Subsidence Parameters and the Assessment of Mine Subsidence Impacts on Natural Features and Items of Surface Infrastructure due to mining Longwalls 27 to 30 at Tahmoor Colliery in support of the SMP Application. Mine Subsidence Engineering Consultants, Report No. MSEC355, Revision B, July 2009. MSEC, (2013). Tahmoor Colliery Longwalls 29 and 30 – The Effects of the Proposed Modified Commencing Ends of Longwalls 29 and 30 at Tahmoor Colliery on the Subsidence Predictions and Impact Assessments. Mine Subsidence Engineering Consultants, Report No. MSEC645, 2013. MSEC, (2013b). Tahmoor House Monitoring Reports during the mining of Longwall 27, Report Series MSEC620. Niche, (2012). Heritage Assessment of Tahmoor House, Niche Environment and Heritage, Project No. -

Newsletter No.100

AssociationAustralian of NativeSocieties Plants for Growing Society (Australia)Australian IncPlants Ref No. ISSN 0725-8755 Newsletter No. 100 – February 2015 GSG Vic Programme 2015 GSG SE Qld Programme 2015 Leader: Neil Marriott Meetings are usually held on the last Sunday 693 Panrock Reservoir Rd, Stawell, Vic. 3380 of the even months. We meet for a communal p 03 5356 2404 or 0458 177 989 morning tea at 9.30am after which the meetings e [email protected] commence at 10.00am. Visitors are always welcome. For more information or to check venues Contact Neil for queries about program for the etc please contact Bryson Easton on 0402 242 180 year. Any members who would like to visit the or Noreen Baxter on (07) 3871 3932 as changes official collection, obtain cutting material or seed, can occur. assist in its maintenance, and stay in our cottage for a few days are invited to contact Neil. Sunday, 22 February Venue: Home of Gail and Adrian Wockner, 5 Horizon Drive, Highfields Qld 4352 Time: 9:30am for 10am meeting Newsletter No. 100 No. Newsletter GSG NSW Programme 2015 Monday, 27 April For details contact Peter Olde 02 4659 6598. Venue: Mt Coot-tha Botanic Garden – meeting in the picnic sheds where road becomes two way 9:30am for 10am meeting Special thanks to the Victorian and New South Wales Time: chapters for this edition of the newsletter. Queensland Topic: Review of the Grevillea Gardens members, please note deadlines on back page for Note the change to Monday is so that members the following newsletter. -

National Recovery Plan for the Stuttering Frog Mixophyes Balbus

National Recovery Plan for the Stuttering Frog Mixophyes balbus David Hunter and Graeme Gillespie Prepared by David Hunter and Graeme Gillespie (Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria). Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) Melbourne, October 2011. © State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2010 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. ISBN 978-1-74242-369-2 (online) This is a Recovery Plan prepared under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, with the assistance of funding provided by the Australian Government. This Recovery Plan has been developed with the involvement and cooperation of a range of stakeholders, but individual stakeholders have not necessarily committed to undertaking specific actions. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds may be subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved. Proposed actions may be subject to modification over the life of the plan due to changes in knowledge. Disclaimer: This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence that may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. An electronic version of this document is available on the Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts website www.environment.gov.au For more information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre 136 186 Citation: Hunter, D. -

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin Animals and Habitat the Basin Supports a Diverse Range of Plants and the Murray–Darling Basin Is Australia’S Largest Animals

The Murray–Darling Basin Basin animals and habitat The Basin supports a diverse range of plants and The Murray–Darling Basin is Australia’s largest animals. Over 350 species of birds (35 endangered), and most diverse river system — a place of great 100 species of lizards, 53 frogs and 46 snakes national significance with many important social, have been recorded — many of them found only in economic and environmental values. Australia. The Basin dominates the landscape of eastern At least 34 bird species depend upon wetlands in 1. 2. 6. Australia, covering over one million square the Basin for breeding. The Macquarie Marshes and kilometres — about 14% of the country — Hume Dam at 7% capacity in 2007 (left) and 100% capactiy in 2011 (right) Narran Lakes are vital habitats for colonial nesting including parts of New South Wales, Victoria, waterbirds (including straw-necked ibis, herons, Queensland and South Australia, and all of the cormorants and spoonbills). Sites such as these Australian Capital Territory. Australia’s three A highly variable river system regularly support more than 20,000 waterbirds and, longest rivers — the Darling, the Murray and the when in flood, over 500,000 birds have been seen. Australia is the driest inhabited continent on earth, Murrumbidgee — run through the Basin. Fifteen species of frogs also occur in the Macquarie and despite having one of the world’s largest Marshes, including the striped and ornate burrowing The Basin is best known as ‘Australia’s food catchments, river flows in the Murray–Darling Basin frogs, the waterholding frog and crucifix toad. bowl’, producing around one-third of the are among the lowest in the world. -

FF Directory

Directory WFF (World Flora Fauna Program) - Updated 30 November 2012 Directory WorldWide Flora & Fauna - Updated 30 November 2012 Release 2012.06 - by IK1GPG Massimo Balsamo & I5FLN Luciano Fusari Reference Name DXCC Continent Country FF Category 1SFF-001 Spratly 1S AS Spratly Archipelago 3AFF-001 Réserve du Larvotto 3A EU Monaco 3AFF-002 Tombant à corail des Spélugues 3A EU Monaco 3BFF-001 Black River Gorges 3B8 AF Mauritius I. 3BFF-002 Agalega is. 3B6 AF Agalega Is. & St.Brandon I. 3BFF-003 Saint Brandon Isls. (aka Cargados Carajos Isls.) 3B7 AF Agalega Is. & St.Brandon I. 3BFF-004 Rodrigues is. 3B9 AF Rodriguez I. 3CFF-001 Monte-Rayses 3C AF Equatorial Guinea 3CFF-002 Pico-Santa-Isabel 3C AF Equatorial Guinea 3D2FF-001 Conway Reef 3D2 OC Conway Reef 3D2FF-002 Rotuma I. 3D2 OC Conway Reef 3DAFF-001 Mlilvane 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3DAFF-002 Mlavula 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3DAFF-003 Malolotja 3DA0 AF Swaziland 3VFF-001 Bou-Hedma 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-002 Boukornine 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-003 Chambi 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-004 El-Feidja 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-005 Ichkeul 3V AF Tunisia National Park, UNESCO-World Heritage 3VFF-006 Zembraand Zembretta 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-007 Kouriates Nature Reserve 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-008 Iles de Djerba 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-009 Sidi Toui 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-010 Tabarka 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-011 Ain Chrichira 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-012 Aina Zana 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-013 des Iles Kneiss 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-014 Serj 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-015 Djebel Bouramli 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-016 Djebel Khroufa 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-017 Djebel Touati 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-018 Etella Natural 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-019 Grotte de Chauve souris d'El Haouaria 3V AF Tunisia National Park, UNESCO-World Heritage 3VFF-020 Ile Chikly 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-021 Kechem el Kelb 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-022 Lac de Tunis 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-023 Majen Djebel Chitane 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-024 Sebkhat Kelbia 3V AF Tunisia 3VFF-025 Tourbière de Dar. -

South Eastern

! ! ! Mount Davies SCA Abercrombie KCR Warragamba-SilverdaleKemps Creek NR Gulguer NR !! South Eastern NSW - Koala Records ! # Burragorang SCA Lea#coc#k #R###P Cobbitty # #### # ! Blue Mountains NP ! ##G#e#org#e#s# #R##iver NP Bendick Murrell NP ### #### Razorback NR Abercrombie River SCA ! ###### ### #### Koorawatha NR Kanangra-Boyd NP Oakdale ! ! ############ # # # Keverstone NPNuggetty SCA William Howe #R####P########## ##### # ! ! ############ ## ## Abercrombie River NP The Oaks ########### # # ### ## Nattai SCA ! ####### # ### ## # Illunie NR ########### # #R#oyal #N#P Dananbilla NR Yerranderie SCA ############### #! Picton ############Hea#thco#t#e NP Gillindich NR Thirlmere #### # ! ! ## Ga!r#awa#rra SCA Bubalahla NR ! #### # Thirlmere Lak!es NP D!#h#a#rawal# SCA # Helensburgh Wiarborough NR ! ##Wilto#n# # ###!#! Young Nattai NP Buxton # !### # # ##! ! Gungewalla NR ! ## # # # Dh#arawal NR Boorowa Thalaba SCA Wombeyan KCR B#a#rgo ## ! Bargo SCA !## ## # Young NR Mares Forest NPWollondilly River NR #!##### I#llawarra Esc#arpment SCA # ## ## # Joadja NR Bargo! Rive##r SC##A##### Y!## ## # ! A ##Y#err#i#nb#ool # !W # #### # GH #C##olo Vale## # Crookwell H I # ### #### Wollongong ! E ###!## ## # # # # Bangadilly NP UM ###! Upper# Ne##pe#an SCA ! H Bow##ral # ## ###### ! # #### Murrumburrah(Harden) Berri#!ma ## ##### ! Back Arm NRTarlo River NPKerrawary NR ## ## Avondale Cecil Ho#skin#s# NR# ! Five Islands NR ILLA ##### !# W ######A#Y AR RA HIGH##W### # Moss# Vale Macquarie Pass NP # ! ! # ! Macquarie Pass SCA Narrangarril NR Bundanoon -

Reconstruction of Historical Riverine Sediment Production on The

Anthropocene 21 (2018) 1–15 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Anthropocene journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ancene Reconstruction of historical riverine sediment production on the goldfields of Victoria, Australia a, a b c c Peter Davies *, Susan Lawrence , Jodi Turnbull , Ian Rutherfurd , James Grove , d e f Ewen Silvester , Darren Baldwin , Mark Macklin a Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University, Bundoora, Victoria, 3086, Australia b Ochre Imprints, 331 Johnston Street, Abbotsford, Victoria, 3067, Australia c School of Geography, Faculty of Science, University of Melbourne, 22 Bouverie Street, Melbourne, Victoria, 3001, Australia d Department of Ecology, Environment and Evolution, School of Life Sciences, College of Science, Health and Engineering, La Trobe University, Wodonga, Victoria, Australia e School of Environmental Sciences, Charles Sturt University, Thurgoon, NSW, 2640, Australia f School of Geography & Lincoln Centre for Water and Planetary Health, College of Science, University of Lincoln, Lincoln, Lincolnshire LN6 7TS, United Kingdom A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: fi fi Received 20 July 2017 A signi cant but previously unquanti ed factor in anthropogenic change in Australian rivers was the release Received in revised form 20 November 2017 of large volumes of sediment produced by gold mining in the 19th century. This material, known historically Accepted 22 November 2017 as ‘sludge’, rapidly entered waterways adjacent to mining areas and caused major environmental damage. Available online 1 December 2017 We interrogate detailed historical records from the colony of Victoria spanning the period 1859 to 1891 to reconstruct the temporal and spatial distribution of sediment volumes released by mining activity. -

Regional Comparison of Impacts from Seven Australian Coal Mine Wastewater Discharges on Downstream River Sediment Chemistry, Sydney Basin, New South Wales Australia

American Journal of Water Science and Engineering 2019; 5(2): 37-46 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajwse doi: 10.11648/j.ajwse.20190502.11 ISSN: 2575-1867 (Print); ISSN: 2575-1875 (Online) Regional Comparison of Impacts from Seven Australian Coal Mine Wastewater Discharges on Downstream River Sediment Chemistry, Sydney Basin, New south Wales Australia Nakia Belmer*, Ian Alexander Wright School of Science and Health, Sydney, Western Sydney University, New South Wales, Australia Email address: *Corresponding author To cite this article: Nakia Belmer, Ian Alexander Wright. Regional Comparison of Impacts from Seven Australian Coal Mine Wastewater Discharges on Downstream River Sediment Chemistry, Sydney Basin, New south Wales Australia. American Journal of Water Science and Engineering. Vol. 5, No. 2, 2019, pp. 37-46. doi: 10.11648/j.ajwse.20190502.11 Received: April 19, 2019; Accepted: May 29, 2019; Published: June 12, 2019 Abstract: This study investigates the accumulation of licensed and regulated coal mine wastewater pollutants from seven coal mines on each mines respective receiving waterways river sediments. Results from this study shows that the coal mine wastewater pollutants are accumulating within river sediments downstream of the coal mine wastewater inflows at varying levels often greater than the ANZECC guidelines for sediment and often above reference condition sediment concentrations. This is of great concern as these pollutants will likely continue to persist in the river sediment and eventually become legacy pollutants. Coal mine wastewater discharges in New South Wales are regulated by the New South Wales Environmental Protection Authority [NSW EPA] and environmental protection of receiving waterways is implemented through Environmental Protection Licenses. -

Impacts of Longwall Coal Mining on the Environment in New South Wales

IMPACTS OF LONGWALL COAL MINING ON THE ENVIRONMENT IN NEW SOUTH WALES Total Environment Centre PO Box A176 www.tec.org.au Sydney South 1235 Ph: 02 9261 3437 January 2007 Fax: 02 9261 3990 Email: [email protected] CONTENTS 01 OVERVIEW 3 02 BACKGROUND 5 2.1 Definition 5 2.2 The Longwall Mining Industry in New South Wales 6 2.3 Longwall Mines & Production in New South Wales 2.4 Policy Framework for Longwall Mining 6 2.5 Longwall Mining as a Key Threatening Process 7 03 DAMAGE OCCURRING AS A RESULT OF LONGWALL MINING 9 3.1 Damage to the Environment 9 3.2 Southern Coalfield Impacts 11 3.3 Western Coalfield Impacts 13 3.4 Hunter Coalfield Impacts 15 3.5 Newcastle Coalfield Impacts 15 04 LONGWALL MINING IN WATER CATCHMENTS 17 05 OTHER EMERGING THREATS 19 5.1 Longwall Mining near National Parks 19 5.2 Longwall Mining under the Liverpool Plains 19 5.3 Longwall Top Coal Caving 20 06 REMEDIATION & MONITORING 21 6.1 Avoidance 21 6.2 Amelioration 22 6.3 Rehabilitation 22 6.4 Monitoring 23 07 KEY ISSUES AND RECOMMENDATIONS 24 7.1 The Approvals Process 24 7.2 Buffer Zones 26 7.3 Southern Coalfields Inquiry 27 08 APPENDIX – EDO ADVICE 27 EDO Drafting Instructions for Legislation on Longwall Mining 09 REFERENCES 35 We are grateful for the support of John Holt in the production of this report and for the graphic design by Steven Granger. Cover Image: The now dry riverbed of Waratah Rivulet, cracked, uplifted and drained by longwall mining in 2006. -

Specified Protected Matters Impact Profiles (Including Risk Assessment)

Appendix F Specified Protected Matters impact profiles (including risk assessment) Roads and Maritime Services EPBC Act Strategic Assessment – Strategic Assessment Report 1. FA1 - Wetland-dependent fauna Species included (common name, scientific name) Listing SPRAT ID Australasian Bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus) Endangered 1001 Oxleyan Pygmy Perch (Nannoperca oxleyana) Endangered 64468 Blue Mountains Water Skink (Eulamprus leuraensis) Endangered 59199 Yellow-spotted Tree Frog/Yellow-spotted Bell Frog (Litoria castanea) Endangered 1848 Giant Burrowing Frog (Heleioporus australicus) Vulnerable 1973 Booroolong Frog (Litoria booroolongensis) Endangered 1844 Littlejohns Tree Frog (Litoria littlejohni) Vulnerable 64733 1.1 Wetland-dependent fauna description Item Summary Description Found in the waters, riparian vegetation and associated wetland vegetation of a diversity of freshwater wetland habitats. B. poiciloptilus is a large, stocky, thick-necked heron-like bird with camouflage-like plumage growing up to 66-76 cm with a wingspan of 1050-1180 cm and feeds on freshwater crustacean, fish, insects, snakes, leaves and fruit. N. oxleyana is light brown to olive coloured freshwater fish with mottling and three to four patchy, dark brown bars extending from head to tail and a whitish belly growing up to 35-60 mm. This is a mobile species that is often observed individually or in pairs and sometimes in small groups but does not form schools and feed on aquatic insects and their larvae (Allen, 1989; McDowall, 1996). E. leuraensis is an insectivorous, medium-sized lizard growing to approximately 20 cm in length. This species has a relatively dark brown/black body when compared to other Eulamprus spp. Also has narrow yellow/bronze to white stripes along its length to beginning of the tail and continuing along the tail as a series of spots (LeBreton, 1996; Cogger, 2000). -

Biodiversity Offset Strategy ALBION PARK RAIL BYPASS

Biodiversity Assessment Report Albion Park Rail Bypass 5726 Final V2.1 B-VII Biodiversity Assessment Report Albion Park Rail Bypass APPENDIX C CREDIT PROFILE As of 15/02/2017 Proposal ID for the assessment: 0035/2017/4182MP Version 1 (Calculator version 4) Assessment type: ‘Major Project’. 5726 Final V2.1 C-I Biodiversity Assessment Report Albion Park Rail Bypass 5726 Final V2.1 C-II Biodiversity Assessment Report Albion Park Rail Bypass 5726 Final V2.1 C-III Biodiversity Assessment Report Albion Park Rail Bypass 5726 Final V2.1 C-IV Biodiversity Assessment Report Albion Park Rail Bypass APPENDIX D SEARS The project is considered State Significant Infrastructure and requires assessment under Part 5.1 of the EP&A Act. Biodiversity factors were assessed in an EIS, as per the Secretary Environmental Assessment Requirements (SEARs) for environmental impact assessment. The Final SEARs was provided by the Department of Planning and Environment on 18 March 2015. 5726 Final V2.1 D-I Biodiversity Assessment Report Albion Park Rail Bypass 5726 Final V2.1 D-II Biodiversity Assessment Report Albion Park Rail Bypass 5726 Final V2.1 D-III Biodiversity Assessment Report Albion Park Rail Bypass 5726 Final V2.1 D-IV Biodiversity Assessment Report Albion Park Rail Bypass 5726 Final V2.1 D-V Biodiversity Assessment Report Albion Park Rail Bypass 5726 Final V2.1 D-VI Biodiversity Assessment Report Albion Park Rail Bypass 5726 Final V2.1 D-VII Biodiversity Assessment Report Albion Park Rail Bypass 5726 Final V2.1 D-VIII Biodiversity Assessment Report Albion Park Rail Bypass APPENDIX E THREATENED SPECIES EVALUATIONS The following evaluation has been carried out for each listed entity of relevance to the project.