17 Croft & Leiper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flora.Sa.Gov.Au/Jabg

JOURNAL of the ADELAIDE BOTANIC GARDENS AN OPEN ACCESS JOURNAL FOR AUSTRALIAN SYSTEMATIC BOTANY flora.sa.gov.au/jabg Published by the STATE HERBARIUM OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA on behalf of the BOARD OF THE BOTANIC GARDENS AND STATE HERBARIUM © Board of the Botanic Gardens and State Herbarium, Adelaide, South Australia © Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Government of South Australia All rights reserved State Herbarium of South Australia PO Box 2732 Kent Town SA 5071 Australia © 2012 Board of the Botanic Gardens & State Herbarium, Government of South Australia J. Adelaide Bot. Gard. 25 (2012) 71–96 © 2012 Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Govt of South Australia Notes on Hibbertia (Dilleniaceae) 8. Seven new species, a new combination and four new subspecies from subgen. Hemistemma, mainly from the central coast of New South Wales H.R. Toelkena & R.T. Millerb a State Herbarium of South Australia, DENR Science Resource Centre, P.O. Box 2732, Kent Town, South Australia 5071 E-mail: [email protected] b 13 Park Road, Bulli, New South Wales 2516 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Increased collections from the Hibbertia-rich vicinity of Sydney, New South Wales, prompted a survey of rarer species to publicise the need for more information ahead of the rapid urban spread. Many of these species were previously misunderstood or are listed as rare and endangered. Thirteen new taxa (in bold) are described and discussed in context with the following seventeen taxa within seven different species groups: 1. H. acicularis group: H. woronorana Toelken; 2. H. humifusa group: H. -

6 Day Lake Mungo Tour Itinerary

I T I N E R A R Y 6 Day Lake Mungo & Outback New South Wales Adventure Get set for some adventure on this epic road trip through Outback New South Wales. Travel in a small group of maximum 8 like minded guests, visit the legendary Lake Mungo National Park and experience the Walls of China, home of the 40000 year old Mungo Man. Enjoy amazing country hospitality and incredible Outback Pubs on this 6 day iconic tour departing Sydney. Inclusions Highly qualified and knowledgeable guide All entry fees including a 30 minute scenic joy flight over Lake Mungo Travel in luxury air-conditioned vehicles All touring Breakfast, lunch and dinner each night, (excluding breakfast on day one and Pick up and drop off from Sydney dinner on day 6) location Comprehensive commentary Exclusions Alcoholic & non alcoholic beverages Gratuities Travel insurance (highly recommended) Souvenirs Additional activities not mentioned Snacks Pick Up 7am - Harrington Street entrance of the Four Seasons Hotel, Sydney. Return 6pm, Day 6 - Harrington Street entrance of the Four Seasons Hotel, Sydney. Alternative arrangements can be made a time of booking for additional pick up locations including home address pickups. Legend B: Breakfast L: Lunch D: Dinner Australian Luxury Escapes | 1 Itinerary: Day 1 Sydney to Hay L, D Depart Sydney early this morning crossing the Blue Mountains and heading North West towards the township of Bathurst, Australia’s oldest inland town. We have some time to stop for a coffee and wander up the main street before rejoining the vehicle. Continue west now to the town of Cowra. -

Macropod Herpesviruses Dec 2013

Herpesviruses and macropods Fact sheet Introductory statement Despite the widespread distribution of herpesviruses across a large range of macropod species there is a lack of detailed knowledge about these viruses and the effects they have on their hosts. While they have been associated with significant mortality events infections are usually benign, producing no or minimal clinical effects in their adapted hosts. With increasing emphasis being placed on captive breeding, reintroduction and translocation programs there is a greater likelihood that these viruses will be introduced into naïve macropod populations. The effects and implications of this type of viral movement are unclear. Aetiology Herpesviruses are enveloped DNA viruses that range in size from 120 to 250nm. The family Herpesviridae is divided into three subfamilies. Alphaherpesviruses have a moderately wide host range, rapid growth, lyse infected cells and have the capacity to establish latent infections primarily, but not exclusively, in nerve ganglia. Betaherpesviruses have a more restricted host range, a long replicative cycle, the capacity to cause infected cells to enlarge and the ability to form latent infections in secretory glands, lymphoreticular tissue, kidneys and other tissues. Gammaherpesviruses have a narrow host range, replicate in lymphoid cells, may induce neoplasia in infected cells and form latent infections in lymphoid tissue (Lachlan and Dubovi 2011, Roizman and Pellet 2001). There have been five herpesvirus species isolated from macropods, three alphaherpesviruses termed Macropodid Herpesvirus 1 (MaHV1), Macropodid Herpesvirus 2 (MaHV2), and Macropodid Herpesvirus 4 (MaHV4) and two gammaherpesviruses including Macropodid Herpesvirus 3 (MaHV3), and a currently unclassified novel gammaherpesvirus detected in swamp wallabies (Wallabia bicolor) (Callinan and Kefford 1981, Finnie et al. -

This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached Copy Is Furnished to the Author for Internal Non-Commerci

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/authorsrights Author's personal copy Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 71 (2014) 149–156 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A multi-locus molecular phylogeny for Australia’s iconic Jacky Dragon (Agamidae: Amphibolurus muricatus): Phylogeographic structure along the Great Dividing Range of south-eastern Australia ⇑ Mitzy Pepper a, , Marco D. Barquero b, Martin J. Whiting b, J. Scott Keogh a a Division of Evolution, Ecology and Genetics, Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia b Department of Biological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia article info abstract Article history: Jacky dragons (Amphibolurus muricatus) are ubiquitous in south-eastern Australia and were one of the Received 25 June 2013 -

Gibraltar Range Parks and Reserves

GIBRALTAR RANGE GROUP OF PARKS (Incorporating Barool, Capoompeta, Gibraltar Range, Nymboida and Washpool National Parks and Nymboida and Washpool State Conservation Areas) PLAN OF MANAGEMENT NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service Part of the Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) February 2005 This plan of management was adopted by the Minister for the Environment on 8 February 2005. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This draft plan of management was prepared by the Northern Directorate Planning Group with assistance from staff of the Glen Innes East and Clarence South Areas of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. The contributions of the Northern Tablelands and North Coast Regional Advisory Committees are greatly appreciated. Cover photograph: Coombadjha Creek, Washpool National Park. © Department of Environment and Conservation (NSW) 2005: Use permitted with appropriate acknowledgment. ISBN 0 7313 6861 4 i FOREWORD The Gibraltar Range Group of Parks includes Barool, Capoompeta, Gibraltar Range, Nymboida and Washpool National Parks and Nymboida and Washpool State Conservation Areas. These five national parks and two state conservation areas are located on the Gibraltar Range half way between Glen Innes and Grafton, and are transected by the Gwydir Highway. They are considered together in this plan because they are largely contiguous and have similar management issues. The Gibraltar Range Group of Parks encompasses some of the most diverse and least disturbed forested country in New South Wales. The Parks contain a stunning landscape of granite boulders, expansive rainforests, tall trees, steep gorges, clear waters and magnificent scenery over wilderness forests. Approximately one third of the area is included on the World Heritage list as part of the Central Eastern Rainforest Reserves of Australia (CERRA). -

Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to Questions on Notice Environment Portfolio

Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications Legislation Committee Answers to questions on notice Environment portfolio Question No: 3 Hearing: Additional Estimates Outcome: Outcome 1 Programme: Biodiversity Conservation Division (BCD) Topic: Threatened Species Commissioner Hansard Page: N/A Question Date: 24 February 2016 Question Type: Written Senator Waters asked: The department has noted that more than $131 million has been committed to projects in support of threatened species – identifying 273 Green Army Projects, 88 20 Million Trees projects, 92 Landcare Grants (http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/3be28db4-0b66-4aef-9991- 2a2f83d4ab22/files/tsc-report-dec2015.pdf) 1. Can the department provide an itemised list of these projects, including title, location, description and amount funded? Answer: Please refer to below table for itemised lists of projects addressing threatened species outcomes, including title, location, description and amount funded. INFORMATION ON PROJECTS WITH THREATENED SPECIES OUTCOMES The following projects were identified by the funding applicant as having threatened species outcomes and were assessed against the criteria for the respective programme round. Funding is for a broad range of activities, not only threatened species conservation activities. Figures provided for the Green Army are approximate and are calculated on the 2015-16 indexed figure of $176,732. Some of the funding is provided in partnership with State & Territory Governments. Additional projects may be approved under the Natinoal Environmental Science programme and the Nest to Ocean turtle Protection Programme up to the value of the programme allocation These project lists reflect projects and funding originally approved. Not all projects will proceed to completion. -

Platypus Collins, L.R

AUSTRALIAN MAMMALS BIOLOGY AND CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT Stephen Jackson © CSIRO 2003 All rights reserved. Except under the conditions described in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, duplicating or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Contact CSIRO PUBLISHING for all permission requests. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Jackson, Stephen M. Australian mammals: Biology and captive management Bibliography. ISBN 0 643 06635 7. 1. Mammals – Australia. 2. Captive mammals. I. Title. 599.0994 Available from CSIRO PUBLISHING 150 Oxford Street (PO Box 1139) Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia Telephone: +61 3 9662 7666 Local call: 1300 788 000 (Australia only) Fax: +61 3 9662 7555 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.publish.csiro.au Cover photos courtesy Stephen Jackson, Esther Beaton and Nick Alexander Set in Minion and Optima Cover and text design by James Kelly Typeset by Desktop Concepts Pty Ltd Printed in Australia by Ligare REFERENCES reserved. Chapter 1 – Platypus Collins, L.R. (1973) Monotremes and Marsupials: A Reference for Zoological Institutions. Smithsonian Institution Press, rights Austin, M.A. (1997) A Practical Guide to the Successful Washington. All Handrearing of Tasmanian Marsupials. Regal Publications, Collins, G.H., Whittington, R.J. & Canfield, P.J. (1986) Melbourne. Theileria ornithorhynchi Mackerras, 1959 in the platypus, 2003. Beaven, M. (1997) Hand rearing of a juvenile platypus. Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw). Journal of Wildlife Proceedings of the ASZK/ARAZPA Conference. 16–20 March. -

Annual Report 2001-2002 (PDF

2001 2002 Annual report NSW national Parks & Wildlife service Published by NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service PO Box 1967, Hurstville 2220 Copyright © National Parks and Wildlife Service 2002 ISSN 0158-0965 Coordinator: Christine Sultana Editor: Catherine Munro Design and layout: Harley & Jones design Printed by: Agency Printing Front cover photos (from top left): Sturt National Park (G Robertson/NPWS); Bouddi National Park (J Winter/NPWS); Banksias, Gibraltar Range National Park Copies of this report are available from the National Parks Centre, (P Green/NPWS); Launch of Backyard Buddies program (NPWS); Pacific black duck 102 George St, The Rocks, Sydney, phone 1300 361 967; or (P Green); Beyers Cottage, Hill End Historic Site (G Ashley/NPWS). NPWS Mail Order, PO Box 1967, Hurstville 2220, phone: 9585 6533. Back cover photos (from left): Python tree, Gossia bidwillii (P Green); Repatriation of Aboriginal remains, La Perouse (C Bento/Australian Museum); This report can also be downloaded from the NPWS website: Rainforest, Nightcap National Park (P Green/NPWS); Northern banjo frog (J Little). www.npws.nsw.gov.au Inside front cover: Sturt National Park (G Robertson/NPWS). Annual report 2001-2002 NPWS mission G Robertson/NPWS NSW national Parks & Wildlife service 2 Contents Director-General’s foreword 6 3Conservation management 43 Working with Aboriginal communities 44 Overview Joint management of national parks 44 Mission statement 8 Aboriginal heritage 46 Role and functions 8 Outside the reserve system 47 Customers, partners and stakeholders -

Factsheet: a Threatened Mammal Index for Australia

Science for Saving Species Research findings factsheet Project 3.1 Factsheet: A Threatened Mammal Index for Australia Research in brief How can the index be used? This project is developing a For the first time in Australia, an for threatened plants are currently Threatened Species Index (TSX) for index has been developed that being assembled. Australia which can assist policy- can provide reliable and rigorous These indices will allow Australian makers, conservation managers measures of trends across Australia’s governments, non-government and the public to understand how threatened species, or at least organisations, stakeholders and the some of the population trends a subset of them. In addition to community to better understand across Australia’s threatened communicating overall trends, the and report on which groups of species are changing over time. It indices can be interrogated and the threatened species are in decline by will inform policy and investment data downloaded via a web-app to bringing together monitoring data. decisions, and enable coherent allow trends for different taxonomic It will potentially enable us to better and transparent reporting on groups or regions to be explored relative changes in threatened understand the performance of and compared. So far, the index has species numbers at national, state high-level strategies and the return been populated with data for some and regional levels. Australia’s on investment in threatened species TSX is based on the Living Planet threatened and near-threatened birds recovery, and inform our priorities Index (www.livingplanetindex.org), and mammals, and monitoring data for investment. a method developed by World Wildlife Fund and the Zoological A Threatened Species Index for mammals in Australia Society of London. -

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Wildlife Parasitology in Australia: Past, Present and Future

CSIRO PUBLISHING Australian Journal of Zoology, 2018, 66, 286–305 Review https://doi.org/10.1071/ZO19017 Wildlife parasitology in Australia: past, present and future David M. Spratt A,C and Ian Beveridge B AAustralian National Wildlife Collection, National Research Collections Australia, CSIRO, GPO Box 1700, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia. BVeterinary Clinical Centre, Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences, University of Melbourne, Werribee, Vic. 3030, Australia. CCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Wildlife parasitology is a highly diverse area of research encompassing many fields including taxonomy, ecology, pathology and epidemiology, and with participants from extremely disparate scientific fields. In addition, the organisms studied are highly dissimilar, ranging from platyhelminths, nematodes and acanthocephalans to insects, arachnids, crustaceans and protists. This review of the parasites of wildlife in Australia highlights the advances made to date, focussing on the work, interests and major findings of researchers over the years and identifies current significant gaps that exist in our understanding. The review is divided into three sections covering protist, helminth and arthropod parasites. The challenge to document the diversity of parasites in Australia continues at a traditional level but the advent of molecular methods has heightened the significance of this issue. Modern methods are providing an avenue for major advances in documenting and restructuring the phylogeny of protistan parasites in particular, while facilitating the recognition of species complexes in helminth taxa previously defined by traditional morphological methods. The life cycles, ecology and general biology of most parasites of wildlife in Australia are extremely poorly understood. While the phylogenetic origins of the Australian vertebrate fauna are complex, so too are the likely origins of their parasites, which do not necessarily mirror those of their hosts. -

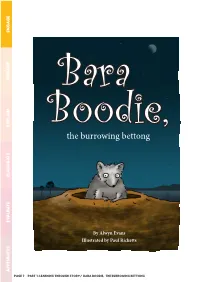

Bara-Boodie.Pdf

ENGAGE E EXPLOR Bara EXPLAIN Boodie, the burrowing bettong ELABORATE E EVALUAT By Alwyn Evans Illustrated by Paul Ricketts ENDICES P AP PAGE 7 PART 1: LEARNING THROUGH STORY / BARA BOODIE, THE BURROWING BETTONG ENGAGE EXPLORE EXPLAIN ELABORATE long, long time ago, boodies lived contentedly all over Australia, in all A sorts of places: from shady woodlands with grasses and shrubs, to wide sandy deserts. EVALUAT Actually my friend, they lived in almost any place they fancied. Bara Boodie and her family’s home was the Australian Western Desert, in E Martu people’s country. They lived in a large cosy nest under a quandong tree, with many friends and neighbours nearby. Actually my friend, boodies loved to make friends with everyone. AP P Bara Boodie, the burrowing bettong ENDICES PART 1: LEARNING THROUGH STORY / BARA BOODIE, THE BURROWING BETTONG PAGE 8 ENGAGE o make their nests snug, Bara’s dad, mum and aunties collected bundles T of spinifex and grasses. Scampering on all fours, they carried their bundles with their fat, prehensile tails, back to their nests. E Actually my friend, they used any soft EXPLOR things they found. As they were small animals, all the family fitted cosily into their nest. Bara was only about 28 centimetres long, and her two brothers weren’t much more. Her mother and aunties were shorter than her father who was 40 centimetres long. At night they slept, curled EXPLAIN up together, with their short-muzzled faces and small rounded ears tucked into their fur. Actually my friend, they looked like one great big, grey, furry ball.