Development from Below

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael R. Hogan West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Hogan, Michael R., "“Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8264. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8264 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael Robert Hogan Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Robert M. -

Windhoek, Namibia Casenote

Transforming Urban Transport – The Role of Political Leadership TUT-POL Sub-Saharan Africa Final Report October 2019 Case Note: Windhoek, Namibia Lead Author: Henna Mahmood Harvard University Graduate School of Design 1 Acknowledgments This research was conducted with the support of the Volvo Foundation for Research and Education. Principal Investigator: Diane Davis Senior Research Associate: Lily Song Research Coordinator: Devanne Brookins Research Assistants: Asad Jan, Stefano Trevisan, Henna Mahmood, Sarah Zou 2 WINDHOEK, NAMIBIA NAMIBIA Population: 2,533,224 (as of July 2018) Population Growth Rate: 1.91% (2018) Median Age: 21.4 GDP: USD$29.6 billion (2017 est.) GDP Per Capita: USD$11,200 (2017 est.) City of Intervention: Windhoek Urban Population: 50% of total population (2018) Urbanization Rate: 4.2% annual rate of change (2015- 2020 est.) Land Area: 910,768 sq km Total Roadways: 48,327 km (2014) Source: CIA Factbook I. POLITICS & GOVERNANCE A. Multi-Scalar Governance Following a 25-year war, Namibia gained independence from South Africa in 1990 under the rule of the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO). Since then, SWAPO has held the presidency, prime minister’s office, the national assembly, and most local and regional councils by a large majority. While opposition parties are active (there are over ten groups), they remain weak and fragmented, with most significant political differences negotiated within SWAPO. The constitution and other legislation dating to the early 1990s emphasize the role of regional and local councils – and since 1998, the government has been engaged in efforts to support decentralization of power.1 However, all levels are connected by SWAPO (through common membership), so power remains effectively centralized. -

The Visual Archive of Colonialism: Germany and Namibia

Photo-essay The Visual Archive of Colonialism: Germany and Namibia George Steinmetz and Julia Hell Colonial memories and images occupy a paradoxi- cal place in Germany. This is due in part to the peculiarities of German colo- nial history, but it also reflects another aspect of German exceptionalism — the legacy of Nazism and the Holocaust. In recent years German colonialism in Southwest Africa (Namibia) has been widely discussed, especially with respect to the attempted extermination of the Ovaherero people in 1904. For reasons explored in this article, these discussions of Germany’s involvement in Southwest Africa have created new and unexpected discursive connections that are reshap- ing colonial memories in both Germany and Namibia. One possible outcome could be a belated decolonization of the landscape of colonial memory in both countries. Postwar Germany was long preoccupied with its National Socialist prehistory; the German colonial past has only started to come into focus more recently.1 The years 2004 – 5 saw numerous commemorative events around the centenary of the 1904 German genocide of the Namibian Ovaherero people and the completion of the controversial Berlin Holocaust Memorial. On one level this is mere coinci- dence. At the same time, there is an increasing entanglement of these two central political topics. But little research has been done on the visual archive of German colonialism, in contrast to the extensive studies made of the public circulation of Thanks to Johannes von Moltke for helping us with the research into the November 2004 von Trotha – Maherero meeting. 1. For a discussion of the ways in which the formerly divided country’s Nazi past was thematized anew after 1989, see Julia Hell and Johannes von Moltke, “Unification Effects: Imaginary Land- scapes of the Berlin Republic,” in “The Cultural Logics of the Berlin Republic,” ed. -

Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location

Revisiting the Windhoek Old Location Henning Melber1 Abstract The Windhoek Old Location refers to what had been the South West African capital’s Main Lo- cation for the majority of black and so-called Colored people from the early 20th century until 1960. Their forced removal to the newly established township Katutura, initiated during the late 1950s, provoked resistance, popular demonstrations and escalated into violent clashes between the residents and the police. These resulted in the killing and wounding of many people on 10 December 1959. The Old Location since became a synonym for African unity in the face of the divisions imposed by apartheid. Based on hitherto unpublished archival documents, this article contributes to a not yet exist- ing social history of the Old Location during the 1950s. It reconstructs aspects of the daily life among the residents in at that time the biggest urban settlement among the colonized majority in South West Africa. It revisits and portraits a community, which among former residents evokes positive memories compared with the imposed new life in Katutura and thereby also contributed to a post-colonial heroic narrative, which integrates the resistance in the Old Location into the patriotic history of the anti-colonial liberation movement in government since Independence. O Lord, help us who roam about. Help us who have been placed in Africa and have no dwelling place of our own. Give us back a dwelling place.2 The Old Location was the Main Location for most of the so-called non-white residents of Wind- hoek from the early 20th century until 1960, while a much smaller location also existed until 1961 in Klein Windhoek. -

A University of Sussex Phd Thesis Available Online Via Sussex

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details The German colonial settler press in Africa, 1898-1916: a web of identities, spaces and infrastructure. Corinna Schäfer Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex September 2017 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: Summary As the first comprehensive work on the German colonial settler newspapers in Africa between 1898 and 1916, this research project explores the development of the settler press, its networks and infrastructure, its contribution to the construction of identities, as well as to the imagination and creation of colonial space. Special attention is given to the newspapers’ relation to Africans, to other imperial powers, and to the German homeland. The research contributes to the understanding of the history of the colonisers and their societies of origin, as well as to the history of the places and people colonised. -

Namibia After 26 Years

On the other side of the picture are elements in the police and to devote their energies instead to making the force who are not neutral, or are trigger-happy, or are country ungovernable. Such lessons are more easily both. They may well be covert rightwingers trying to learnt than forgotten. Ungovernability down there, where sabotage reform. Other rightwingers seem set on making the necklace lies in wait for non-conformists, and the the mining town of Welkom a no-go area for Blacks. They incentive to learn has been largely lost, presents the ANC may not stop there. with a major problem. For Mr De Klerk it certainly makes his task of persuading Whites to accept a future in a non- More disturbing than any of this has been the resurrection racial democracy a thousand times more difficult. of the dreaded "necklace", surely one of the most despicable and dehumanising methods over conceived So what has to be done if what is threatening to become a for dealing with people you think might not be on your lost generation is to be saved, and if something like the side. The leaders of the liberation movement who failed, Namibian miracle is to be made to happen here? for whatever reason, to put a stop to this ghastly practice when it first reared its head amongst their supporters all People need to be given something they feel is important those years ago, may well live to rue that day. Only and constructive to do. What better than building a new Desmond Tutu and a few other brave individuals ever society? risked their own lives to stop it. -

People, Cattle and Land - Transformations of Pastoral Society

People, Cattle and Land - Transformations of Pastoral Society Michael Bollig and Jan-Bart Gewald Everybody living in Namibia, travelling to the country or working in it has an idea as to who the Herero are. In Germany, where most of this book has been compiled and edited, the Herero have entered the public lore of German colonialism alongside the East African askari of German imperial songs. However, what is remembered about the Herero is the alleged racial pride and conservatism of the Herero, cherished in the mythico-histories of the German colonial experiment, but not the atrocities committed by German forces against Herero in a vicious genocidal war. Notions of Herero, their tradition and their identity abound. These are solid and ostensibly more homogeneous than visions of other groups. No travel guide without photographs of Herero women displaying their out-of-time victorian dresses and Herero men wearing highly decorated uniforms and proudly riding their horses at parades. These images leave little doubt that Herero identity can be captured in photography, in contrast to other population groups in Namibia. Without a doubt, the sight of massed ranks of marching Herero men and women dressed in scarlet and khaki, make for excellent photographic opportunities. Indeed, the populär image of the Herero at present appears to depend entirely upon these impressive displays. Yet obviously there is more to the Herero than mere picture post-cards. Herero have not been passive targets of colonial and present-day global image- creators. They contributed actively to the formulation of these images and have played on them in order to achieve political aims and create internal conformity and cohesion. -

The Transformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2009 The Transformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia Katherine Caufield Arnold College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Arnold, Katherine Caufield, "The rT ansformation of the Lutheran Church in Namibia" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 251. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/251 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Introduction Although we kept the fire alive, I well remember somebody telling me once, “We have been waiting for the coming of our Lord. But He is not coming. So we will wait forever for the liberation of Namibia.” I told him, “For sure, the Lord will come, and Namibia will be free.” -Pastor Zephania Kameeta, 1989 On June 30, 1971, risking persecution and death, the African leaders of the two largest Lutheran churches in Namibia1 issued a scathing “Open Letter” to the Prime Minister of South Africa, condemning both South Africa’s illegal occupation of Namibia and its implementation of a vicious apartheid system. It was the first time a church in Namibia had come out publicly against the South African government, and after the publication of the “Open Letter,” Anglican and Roman Catholic churches in Namibia reacted with solidarity. -

S/87%' 6 August 1968 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH

UNITED NATIO Distr . GENERA1 S/87%' 6 August 1968 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH LETTER DATED 5 AUGTJST 1968 FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED NATIONS COUNCIL FOR NAMIBIA ADDRESSED TO 'THE PRESIDENT OF THE SECURITY COUNCIL I have the honour to bring to your attention a message received by the Secretary-General from Mr, Clemens Kapuuo of Windhoek, Namibia, on 24 July lsi'48, stating that non-white Namibians were being forcibly removed from their homes in Windhoek to the new segregated area of Katutura, and requesting the Secretary- General to convene a meeting of the Security Council to consider the matter. According to the message, the deadline for their removal is 31 August 1968, after which date they would not be allowed to continue to live in their present areas of residence. On the same date the Secretary-General transmitted the message in a letter to the United Nations Council for Namibia as he felt that the Council might wish to give the matter urgent attention. A copy of the letter is attached herewith (annex I). The Council considered the matter at its 34th and 35th meetings, held on 25 July 1968 and 5 August 1968 respectively. According to information available to the Council (annex II), the question of the removal of non-whites from their homes in Windhoek to the segregated area 0-P IChtutura first arose in 1959 and was the subject of General Assembly resolution 1567 (XV) of 18 December 1960. At the aforementioned meetings, the Council concluded that the recent actions of the South African Government constitute further evidence of South Africa's continuing defiance of the authority of the United Nations and a further violation of General Assembly resolutions 2145 (XXI), 2248 (S-V), 2325 (XXII) and 2372 (XXII). -

Die Dagboek Van Hendrik Witbooi

Die dagboek van Hendrik Witbooi Kaptein van die Witbooi-Hottentotte 1884-1905 Hendrik Witbooi bron Hendrik Witbooi, Die dagboek van Hendrik Witbooi, Kaptein van die Witbooi-Hottentotte 1884-1905. The Van Riebeeck Society, Cape Town 1929 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/witb002dagb01_01/colofon.php © 2014 dbnl t.o I HOTTENTOT-KAPTEINS. Die drie middelstes is (van links af) Samuel Isaak, Hendrik Witbooi en Isaak Witbooi. Hendrik Witbooi, Die dagboek van Hendrik Witbooi iii Chief events in the life of Hendrik Witbooi. 1884: HENDRIK WITBOOI succeeded his father, Moses, as captain of the Witbooi Hottentots at Gibeon. In the same year he commenced a war against the Hereros which lasted for 8 years. 1892: Concluded peace and returned to his stronghold at Hoornkrans, in the Rehoboth district. 12th April, 1893: Hoornkrans attacked and captured by Major von Francois. Witbooi and his warriors escaped. 15th Sept., 1894: Witbooi surrendered to Governor Leutwein in the Naukluft Mountains. He promised to live peaceably and abandon his warlike and marauding ways. 1894 to 1904: Lived peaceably at Gibeon. On occasions he assisted the German troops against other native tribes. 1904: Broke his promises and agreements and resumed hostilities against the white people in a most treacherous way. 29th Oct., 1905: Wounded in action near Vaalgras (northern part of Keetmanshoop district) and succumbed to these wounds some days later. Hendrik Witbooi, Die dagboek van Hendrik Witbooi vii Introduction. Hendrik Witbooi. This introduction was written by Mr. Gustav Voigts, one of the members of the S.W.A. Scientific Society. He is one of the oldest and most respected inhabitants of South-West Africa. -

Sustainable Urban Transport Master Plan City of Windhoek

Sustainable Urban Transport Master Plan City of Windhoek Final - Main Report 1 Master Plan of City of Windhoek including Rehoboth, Okahandja and Hosea Kutako International Airport The responsibility of the project and its implementation lies with the Ministry of Works and Transport and the City of Windhoek Project Team: 1. Ministry of Works and Transport Cedric Limbo Consultancy services provided by Angeline Simana- Paulo Damien Mabengo Chris Fikunawa 2. City of Windhoek Ludwig Narib George Mujiwa Mayumbelo Clarence Rupingena Browny Mutrifa Horst Lisse Adam Eiseb 3. Polytechnic of Namibia 4. GIZ in consortium with Prof. Dr. Heinrich Semar Frederik Strompen Gregor Schmorl Immanuel Shipanga 5. Consulting Team Dipl.-Volksw. Angelika Zwicky Dr. Kenneth Odero Dr. Niklas Sieber James Scheepers Jaco de Vries Adri van de Wetering Dr. Carsten Schürmann, Prof. Dr. Werner Rothengatter Roloef Wittink Dipl.-Ing. Olaf Scholtz-Knobloch Dr. Carsten Simonis Editors: Fatima Heidersbach, Frederik Strompen Contact: Cedric Limbo Ministry of Works and Transport Head Office Building 6719 Bell St Snyman Circle Windhoek Clarence Rupingena City of Windhoek Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH P.O Box 8016 Windhoek,Namibia, www.sutp.org Cover photo: F Strompen, Young Designers Advertising Layout: Frederik Strompen Windhoek, 15/05/2013 2 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 15 1.1. Purpose ........................................................................................................................................ -

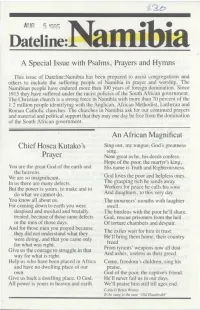

A Special Issue with Psalms, Prayers and Hymns Chief Hosea Kutako 'S

A Special Issue with Psalms, Prayers and Hymns This issue of Dateline:Namibia has been prepared to assist congregations and others to include the suffering people of Namibia in prayer and worship. The Namibian people have endured more than 100 years of foreign domination. Since 1915 they have suffered under the racist policies of the South African government. The Christian church is a strong force in Namibia with more than 70 percent of the 1.2 miUion people identifying with the Anglican. African Methodist. Lutheran and Roman Catholic churches. The churches in Namibia ask for our continued prayers and material and political support that they may one day be free from the domination of the South African government. An African Magnificat Chief Hosea Kutako 's Sing out. my tongue. God ·s greatness sing. Prayer None great a'i he, his deeds confess. Hope of the poor. the martyr's king. You are the great God of the earth and His name is Truth and Righteousness. the heavens. We are so insignificant. God loves the poor and helpless ones. In us there are many defects. The grasping rich he sends away. But the power is yours, to make and to Workers for peace he calls his sons do what we cannot do. And daughters, to this very day. You know all about us. The mourners' mouths with laughter For coming down to earth you were swell. despised and mocked and brutaUy The burdens with the poor he'll share. treated, because of those same defects God, rescue prisoners from the hell in the men of those days.