Lakshmi Bandlamudi E.V. Ramakrishnan Editors Pluralism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![The Legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8445/the-legend-marthanda-varma-1-c-parthiban-sarathi-1-ii-m-a-history-scott-christian-college-autonomous-nagercoil-488445.webp)

The Legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil

ISSN (Online) 2456 -1304 International Journal of Science, Engineering and Management (IJSEM) Vol 2, Issue 12, December 2017 The legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil. Abstract:-- Marthanda Varma the founder of modern Travancore. He was born in 1705. Anizham Tirunal Marthanda Varma rule of Travancore in 1929. Marthanda Varma headquarters in Kalkulam. Marthanda Varma very important policy in Blood and Iron policy. Marthanda Varma reorganised the financial department the palace of Padmanabhapuram was improved and several new buildings. There was improvement of communication following the opening of new Roads and canals. Irrigation works like the ponmana and puthen dams. Marthanda Varma rulling period very important war in Battle of Colachel. The As the Dutch military team captain Eustachius De Lannoy and our soldiers surrendered in Travancore king. Marthanda Varma asked Dutch captain Delannoy to work for the Travancore army Delannoy accepted to take service under the maharaja Delannoy trained with European style of military drill and tactics. Commander in chief of the Travancore military, locally called as valia kapitaan. This king period Padmanabhaswamy temple in Ottakkal mandapam built in Marthanda Varma. The king decided to donate his recalm to Sri Padmanabha and thereafter rule as the deity's vice regent the dedication took place on January 3, 1750 and thereafter he was referred to as Padmanabhadasa Thrippadidanam. The legend king Marthanda Varma 7 July 1758 is dead. Keywords:-- Marthanda Varma, Battle of Colachel, Dutch military captain Delannoy INTRODUCTION English and the Dutch and would have completely quelled the rebels but for the timidity and weakness of his uncle the Anizham Tirunal Marthanda Varma was a ruler of the king who completed him to desist. -

Download Manual for Neolithic Childhood. Art in a False Present, C. 1930 PDF / 948 Kb

A01 The Crisis B18 Children’s Sergei Eisenstein (of Everything) Drawings and Max Ernst A02 Picture Atlas the Questions T. Lux Feininger Projects of the of Origins Julio González 1920sNeolithic (Propyläen B19 The ChildhoodS/O John Heartfield Kunstgeschichte, Function Florence Henri Orbis Pictus, B20 Pornophilia Barbara Hepworth Kulturen der B21 Occultism Hannah Höch ArtErde, Das inBild, aB22 False Automatism, Present,Heinrich Hoerle and Handbuch Dream, Halluci Harry O. Hoyt der Kunstwissen nation, Hypnosis Valentine Hugo schaft) B23c. Image 1930 Space of Paul Klee A03 Art Historical Biology Germaine Krull Images of His B24 Artistic Research: Fernand Léger tory and World Ethnology, Helen Levitt Art Stories Archaeology, Eli Lotar A04 From Ethnolo Physics Len Lye gical Art History B25 Gesture– André Masson to the New “a flash in slow Joan Miró Ethnographic motion through Max von Moos Museums centuries of Rolf Nesch A05 Models of evolution”: Sergei Solomon Nikritin Tempo rality Eisenstein’s Richard Oelze A06 Functions of the Method Wolfgang Paalen “Primitive” B26 The Expedition Jean Painlevé A07 The Art of the as a Medium of Alexandra Povòrina “Primitives” the AvantGarde Jean Renoir A08 The Precise (Dakar–Djibouti GastonLouis Roux Conditionality and Subsequent Franz Wilhelm of Art Missions) Seiwert A09 Carl Einstein, B27 Ethnology of the Kurt Seligmann “Handbuch der White Man? Kalifala Sidibé Kunst” B28 Theories of Fas Jindřich Štyrský A10 “The Ethnologi cism in France Toyen cal Study of Art”: B29 Fascist Anti Raoul Ubac African Sculpture Primitivism: Frits Van den Berghe A11 Archaeology as a “Degenerate Paule Vézelay Media Event Art,” 1937 Wols A12 Prehistory in the B30 Braque/ Catherine Yarrow Abyss of Time Einstein: World A13 The Prehistory Condensation C33 The “Exposition of Art: Rock B31 The Two Lives coloniale inter Drawings and of Myth nationale” and Cave Painting B32 UrCommunism, the AntiColo A14 The Paleolithic/ Expenditure, nialist Impulse Neolithic Age: Proletarianization C34 Afromodernism Mankind’s and “Self Childhood? James L. -

Language Follows Labour: Nikolai Marr's Materialist Palaeontology Of

https://doi.org/10.37050/ci-20_06 ELENA VOGMAN Language Follows Labour Nikolai Marr’s Materialist Palaeontology of Speech CITE AS: Elena Vogman, ‘Language Follows Labour: Nikolai Marr’s Mater- ialist Palaeontology of Speech’, in Materialism and Politics, ed. by Bernardo Bianchi, Emilie Filion-Donato, Marlon Miguel, and Ayşe Yuva, Cultural Inquiry, 20 (Berlin: ICI Berlin Press, 2021), pp. 113–32 <https://doi.org/10.37050/ci-20_06> RIGHTS STATEMENT: Materialism and Politics, ed. by Bernardo Bi- © by the author(s) anchi, Emilie Filion-Donato, Marlon Miguel, and Ayşe Yuva, Cultural Inquiry, 20 (Berlin: Except for images or otherwise noted, this publication is licensed ICI Berlin Press, 2021), pp. 113–32 under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 Interna- tional License. ABSTRACT: This chapter invites the reader to rediscover Nikolai Marr’s scientific work, which is situated at the intersection of archaeology, lin- guistics, and anthropological language theory. Marr’s linguistic mod- els, which Sergei Eisenstein compared to a reading of Joyce’s Ulysses, underwent however multiple waves of critique. His heterodox mater- ialism, originating in an archaeological vision of history and leading to a speculative ‘palaeontology of speech’, reveals a complex vision of time, one traversed by ‘survivals’ and anachronisms. KEYWORDS: palaeontology; gesture; survival; linear speech; material culture; linguistic theory; materialism; historiography; social conflict; Benjamin, Walter; Marr, Nikolai The ICI Berlin Repository is a multi-disciplinary open access archive for the dissemination of scientific research documents related to the ICI Berlin, whether they are originally published by ICI Berlin or elsewhere. Unless noted otherwise, the documents are made available under a Creative Commons Attribution- ShareAlike 4.o International License, which means that you are free to share and adapt the material, provided you give appropriate credit, indicate any changes, and distribute under the same license. -

Mother Tongue: Linguistic Nationalism and the Cult of Translation in Postcommunist Armenia

University of California, Berkeley MOTHER TONGUE: LINGUISTIC NATIONALISM AND THE CULT OF TRANSLATION IN POSTCOMMUNIST ARMENIA Levon Hm. Abrahamian Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Working Paper Series This PDF document preserves the page numbering of the printed version for accuracy of citation. When viewed with Acrobat Reader, the printed page numbers will not correspond with the electronic numbering. The Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies (BPS) is a leading center for graduate training on the Soviet Union and its successor states in the United States. Founded in 1983 as part of a nationwide effort to reinvigorate the field, BPSs mission has been to train a new cohort of scholars and professionals in both cross-disciplinary social science methodology and theory as well as the history, languages, and cultures of the former Soviet Union; to carry out an innovative program of scholarly research and publication on the Soviet Union and its successor states; and to undertake an active public outreach program for the local community, other national and international academic centers, and the U.S. and other governments. Berkeley Program in Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies University of California, Berkeley Institute of Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies 260 Stephens Hall #2304 Berkeley, California 94720-2304 Tel: (510) 643-6737 [email protected] http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~bsp/ MOTHER TONGUE: LINGUISTIC NATIONALISM AND THE CULT OF TRANSLATION IN POSTCOMMUNIST ARMENIA Levon Hm. Abrahamian Summer 1998 Levon Abrahamian is a Professor of Anthropology and head of the project Transfor- mations of Identity in Armenia in the 20th Century at the Institute of Ethnography of Yer- evan State University. -

Bringing Methodology to the Fore: the Anglo-Georgian Expedition to Nokalakevi Paul Everill, Nikoloz Antidze, Davit Lomitashvili, Nikoloz Murgulia

Bringing methodology to the fore: The Anglo-Georgian Expedition to Nokalakevi Paul Everill, Nikoloz Antidze, Davit Lomitashvili, Nikoloz Murgulia Abstract The Anglo-Georgian Expedition to Nokalakevi has been working in Samegrelo, Georgia, since 2001, building on the work carried out by archaeologists from the S. Janashia Museum since 1973. The expedition has trained nearly 250 Georgian and British students in modern archaeological methodology since 2001, and over that same period Georgia has changed enormously, both politically and in its approach to cultural heritage. This paper seeks to contextualise the recent contribution of British archaeological methodology to the rich history of archaeological work in Georgia, and to consider the emergence of a dynamic cultural heritage sector within Georgia since 2004. Introduction A small village in the predominantly rural, western Georgian region of Mingrelia (Samgrelo) hosts a surprising and spectacular historic site. A fortress supposedly established by Kuji, a semi-mythical ruler of west Georgia in the vein of the British King Arthur, provides the stage for the story of an alliance with King Parnavaz of east Georgia (Iberia) and the overthrow of Hellenistic overlords. As a result Nokalakevi has become a potent political symbol of a united, independent Georgia and a backdrop to presidential campaign launches. Known as Tsikhegoji in the Mingrelian dialect, meaning Fortress/ Castle of Kuji, the Byzantine name Archaeopolis (old city) mirrors the literal meaning of the Georgian name, Nokalakevi – ruins where a town was – in suggesting that, even when the Laz and their Byzantine allies fortified the site in the 4th, 5th and 6th centuries AD, the ruins of the Hellenistic period town may have still been visible. -

Sex, Lies, and Red Tape: Ideological and Political Barriers in Soviet Translation of Cold War American Satire, 1964-1988

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2015-07-10 Sex, Lies, and Red Tape: Ideological and Political Barriers in Soviet Translation of Cold War American Satire, 1964-1988 Khmelnitsky, Michael Khmelnitsky, M. (2015). Sex, Lies, and Red Tape: Ideological and Political Barriers in Soviet Translation of Cold War American Satire, 1964-1988 (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/27766 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/2348 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca Allegorie der Übersetzung (2015) Michael G. Khmelnitsky acrylic on canvas (30.4 cm x 30.4 cm) The private collection of Dr. Hollie Adams. M. G. Khmelnitsky ALLEGORY OF TRANSLATION IB №281 A 00276 Sent to typesetting 17.II.15. Signed for printing 20.II.15. Format 12x12. Linen canvas. Order №14. Print run 1. Price 3,119 r. 3 k. Publishing House «Soiuzmedkot» Calgary UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Sex, Lies, and Red Tape: Ideological and Political Barriers in Soviet Translation of Cold War American Satire, 1964-1988 by Michael Khmelnitsky A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA JULY, 2015 © Michael Khmelnitsky 2015 Abstract My thesis investigates the various ideological and political forces that placed pressures on cultural producers, specifically translators in the U.S.S.R., during the Era of Stagnation (1964- 1988). -

Community Oriented Storytelling Brochure

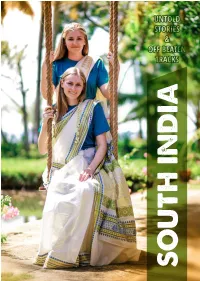

TABLE OF CONTENTS Kerala Experience -14 N/15 D 05 - 07 South India Lifescapes (Tamilnadu - Kerala - Karnataka) -18 N/19 D 08 - 10 Dravidian Routes (Exclusive Tamilnadu) -13 N/14 D 11 - 12 Brief South (Tamilnadu & Kerala) - 13 N/14 D 12 - 14 Deccan Circuit (Karnataka - Goa - Mumbai) -13 N/14 D 14 - 16 Tiger Trail (Western Ghats) - 13 N/14 D 16 - 18 Active Extension (Trekking Tour) - 04 N/05 D 18 - 19 River Nila Experience (North Kerala) -14 N/15 D 20 - 24 Short Stories - Short Experience Programs 25 School Stories - Cochin, Kerala 25 Village Life Stories - Poothotta, Kerala 25 Cochin Royal Heritage Trail - Thripunithura, Kerala 26 Cultural Immersion (Kathakali) - Cochin, Kerala 26 Mattancherry Chronicles - Cochin, Kerala 26 - 27 Pepper Trails - Cochin, Kerala 27 Village Life Stories - Manakkodam, Kerala 27 Breakfast Trail - Manakkodam, Kerala 27 Rani's Kitchen - Alleppey, Kerala 28 Tribal Stories - Marayoor, Kerala 28 Tea Trail - Munnar, Kerala 28 Meet The Nairs - Trichur, Kerala 28 - 29 Royal Family Experience - Nilambur, Kerala 29 Royal cuisine stories at Turmerica - Wayanad, Kerala 29 Tribal Cooking stories - Wayanad, Kerala 29 - 30 Madras Chronicles - Chennai, Tamilnadu 30 Meet The Franco - Tamils - Pondicherry 30 Along the River Kaveri - Tanjore Village Stories - Tanjore, Tamilnadu 30 - 31 Arts & Crafts of Tanjore - Tanjore, Tamilnadu 31 03 SOUTH INDIA A different world of Life Stories, Culture & Cuisine Travel a Dream Travel is about listening to stories - stories of the experience the beautiful part of our Country - South & making up of a country, a region, culture and its people. At Western India. Our showcased programs are only pilot ones Keralavoyages, we help you to listen to the local stories and or travelled by one of our travelers but if you have a different the life around. -

Nikolai Marr's Critique of Indo-European Philology and the Subaltern Critique of Brahman Nationalism in Colonial India

This is a repository copy of Nikolai Marr’s Critique of Indo-European Philology and the Subaltern Critique of Brahman Nationalism in Colonial India. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/126702/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Brandist, C. (2018) Nikolai Marr’s Critique of Indo-European Philology and the Subaltern Critique of Brahman Nationalism in Colonial India. Interventions: international journal of postcolonial studies. ISSN 1369-801X https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2017.1421043 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Nikolai Marr’s Critique of Indo-European Philology and the Subaltern Critique of Brahman Nationalism in Colonial India. After a long period during which his works were regarded as little more than a cautionary tale about the usurpation of science by ideology, the controversial Georgian philologist and archaeologist Nikolai Iakovlevich Marr has made an unexpected reappearance on the intellectual scene. -

25 Years of Independence, Georgia's

Georgians may be rightfully proud of their ancient his- tory, but their modern state has just passed a stage of infancy. Approximately a quarter of century ago, Georgia started to build a new nation and a new state. The opening conditions were not promising. Under the civil wars, col- lapsing economic system and nonexistent public services not many people believed in viability of the Georgian state. Today, twenty five years later Georgia still faces multiple challenges: territorial, political, economic, social, etc. But on the balance, it is an accomplished state with fairly func- tional institutions, vibrant civil society, growing economy, a system of regional alliances and close cooperative relations with a number of international actors, European Union and NATO among them. How the progress was achieved, in which areas Georgia is more successful and what the greatest deficits are which it still faces and how to move forward are the questions this volume tries to answer. This book tries to reconstruct major tasks that the Georgian state was facing in the beginning, and then track success and failure in each of those areas till today. Thus, the authors of six chapters deal with nation-, state-, and democracy-building in Georgia as well as evolution of civil society, economic development, and last but not least, the role and place of Georgia in the new post-Cold-War interna- tional system. We very much hope that this volume will contribute to the debate about Georgia’s development. Since it is based on academic research, the authors tried to make it a good and useful read for anybody interested in all matters of Georgia. -

MARTHANDAVARMA – the Legend of Modern Travancore

International Journal of Research ISSN NO:2236-6124 MARTHANDAVARMA – The Legend of Modern Travancore Sharmila Prasad R. Ph.D. Research Scholar (Reg. No.1035/2014) Research Department of History, Alagappa Government Arts College, Karaikkudi – 630 003. Tamil Nadu, India. (Affiliated to Alagappa University, Karaikudi – 630003, Tamil Nadu, India.) Dr. C. Lawrance Assistant Professor (Research Supervisor) Research Department of History, Alagappa Government Arts College, Karaikkudi – 630 003. Tamil Nadu, India. (Affiliated to Alagappa University, Karaikudi – 630003, Tamil Nadu, India.) ----------------------------- ABSTRACT The Travancore, erstwhile Hindu feudal kingdom, is one of the most scenic and charming portions of India. The term Travancore is the anglicized form of Thiruvithamkodu which means 'the abode of prosperity'. It derived its name from the word Thiruvithamcode, its one- time capital. Anizham Thirunal Marthandavarma was the King of Travancore from 1729 A.D until his death in 1758 A.D. The accession of Marthandavarma to the throne marked the commencement of a new era in the annals of the administrative past of Travancore. Within a few years of his accession, he was able to put down the over mighty subjects and restore peace and order throughout his country. Later, he waged continuous wars against several of his northern neighbours and conquered them. These struggles with his enemies did not prevent him from establishing an effective administration and undertaking several nation-building activities. King Marthandavarma was the only Indian king to beat the European army at the Battle of Colachel against the Dutch. For administrative convenience, Marthandavarma re-organised all departments. He followed Blood and Iron policy in uniting the Travancore kingdom. -

The Policy of Ethnic Enclosure in the Caucasus

Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………. iii INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………….. 1 Part I Ethnic Enclosure: Language, Myths and Ethnic Groups in the Soviet Union CHAPTER ONE: 1 Language, Ethnic Conflict and Ethnic Enclosure 11 1.1 Ethnic Group and Language …………………………………………….. 11 1.2 Language and Modernization ………………………………………… 15 1.3 Language in Ethnic Conflict ……………………………………………... 18 1.4 Ethnic Enclosure ……………………………………………………… 25 CHAPTER TWO: 2 Language Policy and the Soviet Ethno-Territorial Division 33 2.1 The Soviet Approaches to Nationality Policy…………………………… 33 2.2 Language Policy and Ethnic Identification in the Soviet Union………… 45 3 CHAPTER THREE: Language and the Construction of Ethnogenetic Myths in the Soviet Union 58 3.1 Historians and the Process of Myths Formation ………………………… 58 3.2 Cycles of Ethnogenetic Myths Formation in the USSR………………… 68 3.3 Myths and the Teaching of Local Histories in Schools of Soviet Autonomies………………………………………………………………… 71 Part II The Policy of Ethnic Enclosure in the Caucasus 4 CHAPTER FOUR: The Formation of Abkhazian and Georgian Ethnogenetic Myths 79 4.1 Previous Studies of the Georgian-Abkhazian Conflict …………………… 79 4.2 Languages in Abkhazia: A Linguistic Perspective……………………… 82 4.3 Russian Colonization of Abkhazia in the 19th Century and the Changes in Ethno-Demographic Composition of the Area ……………………… 87 4.4 Language and the Issue of Abkhazian Autonomy in the Democratic Republic of Georgia ……………………………………………………… 95 CHAPTER FIVE: 5 Language and Myths in Soviet Abkhazia (1921-1988) -

40Th Annual General Body Meeting Held on 14Th July 2018

Vol. XXII | No. 3 | July - August 2018 40th Annual General Body Meeting held on 14th July 2018 Newly elected Office Bearers of KMPA R. Gopakumar Biju Jose Raju N. Kutty Shajimon C.A. D. Manmohan Shenoy K. Madhusoodhanan T.F. James President Hon. Gen. Secretary Treasurer Joint Secretary VP, Central VP, South VP, North Print Miracle Vol. XXII No. 3 RNI Reg. No. 65957/96 The Official Journal of Kerala Master Printers Association July - August 2018 Editor : S. Saji The Flood Experience - a KMPA perspective Editorial Board : Rajesh G. 06 R. Haridas The floods that ravaged Kerala affected lakhs of people in the Ajith Jose C. State. The printing fraternity suffered huge losses. Yeldho K. George Raju N. Kutty narrates his journey to the flood affected areas. Associate Editor : Mukundan Menon Flood of misery 14 Office Bearers of KMPA The government has pegged the value of losses at 24,200 President : R. Gopakumar crores of rupees, nearly 24 percent of the amount the state had General Secretary : Biju Jose spent for the entire year, says Mukundan Menon in his report Treasurer : Raju N. Kutty Immediate Past President : S. Saji 16 40th Annual General Body Meeting Joint Secretary : Shajimon C.A. AGM of KMPA held on 14th July, 2018. Immediate Past Co-ordinator : O. Venugopal President S. Saji highlighted his team’s achievements during Vice Presidents the speech. Central : D. Manmohan Shenoy North : T.F. James Rowing with the Tidal Waves of Printing 21 South : K. Madhusoodhanan The ‘54 Divasathe Aattakkathakal’ was the biggest book brought out by this printing unit.