Lakshmi Bandlamudi EV Ramakrishnan Editors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![The Legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8445/the-legend-marthanda-varma-1-c-parthiban-sarathi-1-ii-m-a-history-scott-christian-college-autonomous-nagercoil-488445.webp)

The Legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil

ISSN (Online) 2456 -1304 International Journal of Science, Engineering and Management (IJSEM) Vol 2, Issue 12, December 2017 The legend Marthanda Varma [1] C.Parthiban Sarathi [1] II M.A History, Scott Christian College(Autonomous), Nagercoil. Abstract:-- Marthanda Varma the founder of modern Travancore. He was born in 1705. Anizham Tirunal Marthanda Varma rule of Travancore in 1929. Marthanda Varma headquarters in Kalkulam. Marthanda Varma very important policy in Blood and Iron policy. Marthanda Varma reorganised the financial department the palace of Padmanabhapuram was improved and several new buildings. There was improvement of communication following the opening of new Roads and canals. Irrigation works like the ponmana and puthen dams. Marthanda Varma rulling period very important war in Battle of Colachel. The As the Dutch military team captain Eustachius De Lannoy and our soldiers surrendered in Travancore king. Marthanda Varma asked Dutch captain Delannoy to work for the Travancore army Delannoy accepted to take service under the maharaja Delannoy trained with European style of military drill and tactics. Commander in chief of the Travancore military, locally called as valia kapitaan. This king period Padmanabhaswamy temple in Ottakkal mandapam built in Marthanda Varma. The king decided to donate his recalm to Sri Padmanabha and thereafter rule as the deity's vice regent the dedication took place on January 3, 1750 and thereafter he was referred to as Padmanabhadasa Thrippadidanam. The legend king Marthanda Varma 7 July 1758 is dead. Keywords:-- Marthanda Varma, Battle of Colachel, Dutch military captain Delannoy INTRODUCTION English and the Dutch and would have completely quelled the rebels but for the timidity and weakness of his uncle the Anizham Tirunal Marthanda Varma was a ruler of the king who completed him to desist. -

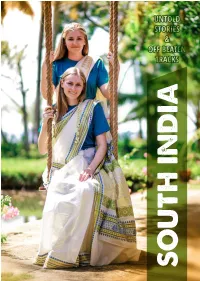

Community Oriented Storytelling Brochure

TABLE OF CONTENTS Kerala Experience -14 N/15 D 05 - 07 South India Lifescapes (Tamilnadu - Kerala - Karnataka) -18 N/19 D 08 - 10 Dravidian Routes (Exclusive Tamilnadu) -13 N/14 D 11 - 12 Brief South (Tamilnadu & Kerala) - 13 N/14 D 12 - 14 Deccan Circuit (Karnataka - Goa - Mumbai) -13 N/14 D 14 - 16 Tiger Trail (Western Ghats) - 13 N/14 D 16 - 18 Active Extension (Trekking Tour) - 04 N/05 D 18 - 19 River Nila Experience (North Kerala) -14 N/15 D 20 - 24 Short Stories - Short Experience Programs 25 School Stories - Cochin, Kerala 25 Village Life Stories - Poothotta, Kerala 25 Cochin Royal Heritage Trail - Thripunithura, Kerala 26 Cultural Immersion (Kathakali) - Cochin, Kerala 26 Mattancherry Chronicles - Cochin, Kerala 26 - 27 Pepper Trails - Cochin, Kerala 27 Village Life Stories - Manakkodam, Kerala 27 Breakfast Trail - Manakkodam, Kerala 27 Rani's Kitchen - Alleppey, Kerala 28 Tribal Stories - Marayoor, Kerala 28 Tea Trail - Munnar, Kerala 28 Meet The Nairs - Trichur, Kerala 28 - 29 Royal Family Experience - Nilambur, Kerala 29 Royal cuisine stories at Turmerica - Wayanad, Kerala 29 Tribal Cooking stories - Wayanad, Kerala 29 - 30 Madras Chronicles - Chennai, Tamilnadu 30 Meet The Franco - Tamils - Pondicherry 30 Along the River Kaveri - Tanjore Village Stories - Tanjore, Tamilnadu 30 - 31 Arts & Crafts of Tanjore - Tanjore, Tamilnadu 31 03 SOUTH INDIA A different world of Life Stories, Culture & Cuisine Travel a Dream Travel is about listening to stories - stories of the experience the beautiful part of our Country - South & making up of a country, a region, culture and its people. At Western India. Our showcased programs are only pilot ones Keralavoyages, we help you to listen to the local stories and or travelled by one of our travelers but if you have a different the life around. -

MARTHANDAVARMA – the Legend of Modern Travancore

International Journal of Research ISSN NO:2236-6124 MARTHANDAVARMA – The Legend of Modern Travancore Sharmila Prasad R. Ph.D. Research Scholar (Reg. No.1035/2014) Research Department of History, Alagappa Government Arts College, Karaikkudi – 630 003. Tamil Nadu, India. (Affiliated to Alagappa University, Karaikudi – 630003, Tamil Nadu, India.) Dr. C. Lawrance Assistant Professor (Research Supervisor) Research Department of History, Alagappa Government Arts College, Karaikkudi – 630 003. Tamil Nadu, India. (Affiliated to Alagappa University, Karaikudi – 630003, Tamil Nadu, India.) ----------------------------- ABSTRACT The Travancore, erstwhile Hindu feudal kingdom, is one of the most scenic and charming portions of India. The term Travancore is the anglicized form of Thiruvithamkodu which means 'the abode of prosperity'. It derived its name from the word Thiruvithamcode, its one- time capital. Anizham Thirunal Marthandavarma was the King of Travancore from 1729 A.D until his death in 1758 A.D. The accession of Marthandavarma to the throne marked the commencement of a new era in the annals of the administrative past of Travancore. Within a few years of his accession, he was able to put down the over mighty subjects and restore peace and order throughout his country. Later, he waged continuous wars against several of his northern neighbours and conquered them. These struggles with his enemies did not prevent him from establishing an effective administration and undertaking several nation-building activities. King Marthandavarma was the only Indian king to beat the European army at the Battle of Colachel against the Dutch. For administrative convenience, Marthandavarma re-organised all departments. He followed Blood and Iron policy in uniting the Travancore kingdom. -

40Th Annual General Body Meeting Held on 14Th July 2018

Vol. XXII | No. 3 | July - August 2018 40th Annual General Body Meeting held on 14th July 2018 Newly elected Office Bearers of KMPA R. Gopakumar Biju Jose Raju N. Kutty Shajimon C.A. D. Manmohan Shenoy K. Madhusoodhanan T.F. James President Hon. Gen. Secretary Treasurer Joint Secretary VP, Central VP, South VP, North Print Miracle Vol. XXII No. 3 RNI Reg. No. 65957/96 The Official Journal of Kerala Master Printers Association July - August 2018 Editor : S. Saji The Flood Experience - a KMPA perspective Editorial Board : Rajesh G. 06 R. Haridas The floods that ravaged Kerala affected lakhs of people in the Ajith Jose C. State. The printing fraternity suffered huge losses. Yeldho K. George Raju N. Kutty narrates his journey to the flood affected areas. Associate Editor : Mukundan Menon Flood of misery 14 Office Bearers of KMPA The government has pegged the value of losses at 24,200 President : R. Gopakumar crores of rupees, nearly 24 percent of the amount the state had General Secretary : Biju Jose spent for the entire year, says Mukundan Menon in his report Treasurer : Raju N. Kutty Immediate Past President : S. Saji 16 40th Annual General Body Meeting Joint Secretary : Shajimon C.A. AGM of KMPA held on 14th July, 2018. Immediate Past Co-ordinator : O. Venugopal President S. Saji highlighted his team’s achievements during Vice Presidents the speech. Central : D. Manmohan Shenoy North : T.F. James Rowing with the Tidal Waves of Printing 21 South : K. Madhusoodhanan The ‘54 Divasathe Aattakkathakal’ was the biggest book brought out by this printing unit. -

Library Details the Library Has Separate Reference Section/ Journals Section and Reading Room : Yes

ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST’S COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, NEDUMKUNNAM Library Details The Library has separate reference section/ Journals section and reading room : Yes Number of books in the library : 8681 Total number of educational Journals/ periodicals being subscribed : 23 Number of encyclopaedias available in the library : 170 Number of books available in the reference section of the library : 1077 Seating capacity of the reading room of the library : 75 Books added in Last quarter Number of books in the library : 73 Total number of educational Journals/ periodicals being subscribed : 1 Number of books available in the reference section of the library : 9 Library Stock Register ACC_NO BOOK_NAME AUTHOR 1 Freedom At Midnight Collins, Larry & Lapierre, Dominique 2 Culture And Civilisation Of Ancient India In Historical Outline Kosambi,D.D. 3 Teaching Of History: A Practical Approach Aggarwal, J. C. 4 Teaching Of History:a Practical Approach Aggarwal,j.c. 5 School Inspection Ststem:a Modern Approach Singhal, R. P. 6 Teaching Of Social Studies : A Practical Approach Aggarwal, J. C. 7 Teaching Of Social Studies: A Practical Approach Aggarwal, J. C. 8 School Inspection System: A Modern Approach Aggarwal, J. C. 9 Fundamentals Of Classroom Teaching Taiwa, Adedison A. 10 Introduction To Statistical Methods Gupta, C. B. & Gupta, Vijay 11 Textbook Of Botany Vol.2 Pandey, S. N. & Others 12 Textbook Of Botany. Vol 1 Pandey, S. N. & Trivedi, P. S. 13 Textbook Of Botany. Vol.3 Pandey, S. N. & Chadha A. 14 Principles Of Education Venkateswaran, S. 15 National Policy On Education: An Overview Ram, Atma & Sharma, K. D. -

Kunchan Nambiar - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Kunchan Nambiar - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Kunchan Nambiar(1705 – 1770) Kunchan Nambiar was an early Malayalam language poet, performer, satirist and the inventor of local art form Ottamtullal. He is often considered as the master of Malayalam satirist poetry. Kunchan Nambiar spent his early childhood at Killikkurussimangalam, his boyhood at Kudamalur and youth at Ambalappuzha. In 1748 he moved to the court of King Marttanda Varma of Travancore Kingdom and later to the court of his successor Dharma Raja. He had already written several of his works before leaving Aluva. Scholars like Mani Madhava Cakyar have the opinion that he and the Sanskrit poet Rama Panivada are the same. ("Panivada" means "Nambiar" in Sanskrit). Nambiar's poetry lacks the high seriousness such as we find in Ezhuthachan. The difference here is significant. The two are complementary. Just as Kilipattu seems to express the total personality of a writer like Ezhuthachan, the Thullal brings out the characteristic features of the personality of Nambiar. Between them they cover the entire spectrum of humanity, the entire gamut of human emotions. No other Kilipattu has come anywhere near Ezhuthachan's Ramayanam and Mahabharatam, no other Thullal composition is ever likely to equal the best of Nambiar's compositions. <b> Literary Career </b> The chief contribution of Kunchan Nambiar is the popularization of a performing art known as Tullal. The word literally means "dance", but under this name Nambiar devised a new style of verse narration with a little background music and dance-like swinging movement to wean the people away from the Cakyar Kuttu, which was the art form popular till then. -

Lakshmi Bandlamudi E.V. Ramakrishnan Editors Pluralism

Lakshmi Bandlamudi E.V. Ramakrishnan Editors Bakhtinian Explorations of Indian Culture Pluralism, Dogma and Dialogue Through History Bakhtinian Explorations of Indian Culture [email protected] Lakshmi Bandlamudi • E.V. Ramakrishnan Editors Bakhtinian Explorations of Indian Culture Pluralism, Dogma and Dialogue Through History 123 [email protected] Editors Lakshmi Bandlamudi E.V. Ramakrishnan Department of Psychology School of Language, Literature and Culture LaGuardia Community College Studies New York, NY Central University of Gujarat USA Gandhinagar, Gujarat India ISBN 978-981-10-6312-1 ISBN 978-981-10-6313-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6313-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017949132 © Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2018 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

EN002 Malayalam Literature and the Bhakti Movement (0 Credits)

EN002 Malayalam Literature and the Bhakti Movement (0 Credits) Course overview: This course will make the Ph D students familiar with the origin of Malayalam Literature and the growth and development of the Bhakti Movement in Malayalam. It will expose them to the major Bhakti poets and their works. Course outcomes: CO1: Expose the students to the origin and development of Malayalam Literature CO2: Make them familiar with the Bhakti poets of different eras starting from the ancient to the modern era. CO3: Develop a critical awareness and an aesthetic appreciation of Bhakti poetry in Malayalam Syllabus Unit1: The origin and devolpment of Malayalam Literature: Bhakti Prasthanam in Kerala, Pattu Sahityam, Manipravalam, Gadha, Kilippattu, Vanchippattu, Mapila pattu and Attakkadha. Unit 2: The Triumvirates of Bhakti Movement in Kerala: Ezhuthachan, Cherusseri Namboodiri, Kunchan Nambiar. Unit 3: Ezhuthachan and the Bhakti Movement in Kerala Ezhuthachan and Bhakti Movement; Social and Cultural background, Kilippattu -origin and characteristics, Ezhuthachan's Contribution to language & Literature. Adhyatma Ramayanam, Bharatam, other works attributed to him, Harinama Keerthanam and Bhagavatam Unit 4: Other Bhakti Poets of Kerala Poontanam, Vilvamangalam, Melpattur Narayana Bhattathiripaad, Thunchathu Ezhuthachan, Kumaran Asaan Unit 5: Modern Bhakti triumvirates of Kerala: Kumaran Asan, Uloor S Parameswara Iyer, Vallathol Narayana Menon Reference Books: A short History of Malayalam language and literature- S.K Nayar. A short History of Malayalam language and literature- S.K Nayar. Ulloor : Kerala Sahitya Charitram Vol. II & III 2. Geroge K.M. (Ed.): Sahitya Charitram Prastarangaliloode 3. Krishnnapillai. N: Karialiyude Katha 4. Leelavati. M.: Malayala Kavitha Sahitya Charitram 5. Evoor Parameswaran :-Nambiyarum Tullal Sahityavum 6. -

Download Book

TEXT FLY WITH IN THE BOOK ONLY W > U3 m<OU-166775 >m >E JO 7J z^9 xco =; _i > 1 3-6-75--10,000. UNIVERSITY LIBRARY f * * ^ 4- No. A- P | <Z Accession No. 6 3 7 2. y O, . /I Title z/i' ^ /e^tTe This b-mk sh ) ilri b: returned on or before the date last marked below. THE ART OF KATHAKALI By GAYANACHARYA AVINASH C. PANDEYA With a Foreword by GURU GOPI NATH Introduction by His HIGHNESS MAHARANA SHREE VIJAYADEVJI RANA MAHARAJA SAHEB OF DHARAMPUR (SURAT) 1961 KITABISTAN ALLAHABAD First Published in 1943 pccond Edition 1961 PUBLISHED BY K1TABISTAN, ALLAHABAD ( INDIA) PRINTED AT THE SAMMELAN MUDRANALAYA, PRAYAO TO MY MOTHER FOREWORD IN making a critical study of the art and dance of Kathakaji, the ancient dance-drama of Kerala, Gayanacharya Avinash C. Pand6ya has produced this comprehensive book of an unparalleled nature. I feel no less pleasure than great honour that I am invi- ted to express a few words on it. So far none has dealt with this subject in any language so elaborately and so systematically as this young authority on Indian music and dancing has. He has presented the entire technical subtlety in a lucid style making it to rank as the first book on Kathakali literature, dance and art. Its authenticity as the first today and the first tomorrow shall ever guide all dancers, students, commentators and contemporaries of all ages. The book deals with the origin of Kathakali, its art and dance, rasas and costume and make-up, and gestural code; and makes wide study on the origin of Mudrds their permutation and combi- nation. -

Internationalization and Math

Internationalization and Math Test collection Made by ckepper • English • 2 articles • 156 pages Contents Internationalization 1. Arabic alphabet . 3 2. Bengali alphabet . 27 3. Chinese script styles . 47 4. Hebrew language . 54 5. Iotation . 76 6. Malayalam . 80 Math Formulas 7. Maxwell's equations . 102 8. Schrödinger equation . 122 Appendix 9. Article ourS ces and Contributors . 152 10. Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors . 154 Internationalization Arabic alphabet Arabic Alphabet Type Abjad Languages Arabic Time peri- 356 AD to the present od Egyptian • Proto-Sinaitic ◦ Phoenician Parent ▪ Aramaic systems ▪ Syriac ▪ Nabataean ▪ Arabic Al- phabet Arabic alphabet | Article 1 fo 2 3 َْ Direction Right-to-left األ ْب َج ِد َّية :The Arabic alphabet (Arabic ا ْل ُح ُروف al-ʾabjadīyah al-ʿarabīyah, or ا ْل َع َربِ َّية ISO ْ al-ḥurūf al-ʿarabīyah) or Arabic Arab, 160 ال َع َربِ َّية 15924 abjad is the Arabic script as it is codi- Unicode fied for writing Arabic. It is written Arabic alias from right to left in a cursive style and includes 28 letters. Most letters have • U+0600–U+06FF contextual letterforms. Arabic • U+0750–U+077F Originally, the alphabet was an abjad, Arabic Supplement with only consonants, but it is now con- • U+08A0–U+08FF sidered an "impure abjad". As with other Arabic Extended-A abjads, such as the Hebrew alphabet, • U+FB50–U+FDFF scribes later devised means of indicating Unicode Arabic Presentation vowel sounds by separate vowel diacrit- range Forms-A ics. • U+FE70–U+FEFF Arabic Presentation Consonants Forms-B • U+1EE00–U+1EEFF The basic Arabic alphabet contains 28 Arabic Mathematical letters. -

Indian Dalit Literature — a Reflection of Cultural Marginality

International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, Vol. 2, No. 4, December 2016 Indian Dalit Literature — A Reflection of Cultural Marginality Soumya Nair Anoop Kumar has become an identity to a segregated class of people like we Abstract—The paper attempts to trace the impact of Indian call Negroes/ Blacks in Afro-America, the Aborigines in Dalit Literature focusing on the question of Identity as well as Australia and the Maoris in New Zealand. This genre of Equality; cruelties by the subjugated group, exploitation of the literature can be a reconstruction of the past. Dalit literature untouchables, caste segregation, oppression by the dominant for a long time was ignored and not considered seriously in class, suppression of women turn out to be the subjects of this new genre of subaltern literature. The voiceless anger from the the mainstream literary genres. The fundamental human deep-rooted souls of the downtrodden weaker minds are clearly values like liberty, fraternity; equality, which can be the key depicted in the writings which are articulated as Poems, short factors of the Dalit literature, was a quest for identity in the stories, novels or essays along with their biographical accounts society. Dalitness was reputable with different ideology in many case. corresponding with Dalit consciousness, Dalit aesthetics, Dalit arts, Dalit revolution and so on. Index Terms—Identity, marginality, resistance, un-touchability. It persists as eternal in the attitudes of the voiced towards the voiceless. Never Dalits will be totally evacuated from the society. Dalits are like water. Water freeze and turn into ice I. INTRODUCTION and melt back to water again. -

Kerala Society and Culture: Ancient and Medieval

KERALA SOCIETY AND CULTURE: ANCIENT AND MEDIEVAL V SEMESTER B.A HISTORY: CORE COURSE (2014 Admission onwards) UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION 767 School of Distance Education UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION V SEMESTER B.A HISTORY: CORE COURSE KERALA SOCIETY AND CULTURE: ANCIENT AND MEDIEVAL Prepared by Sri: SUNILKUMAR.G ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY N.S.S. COLLEGE, MANJERI Scrutinised by Sri: Ashraf koyilothan Kandiyil Chairman, BOS- History (UG) Settings & Lay Out By : SDE: Computer Cell Kerala Society And Culture:Ancient And Medieval Page 2 School of Distance Education Module-I Kerala’s Physiographical Features and Early History of the Region Module-II Polity and Society in the Perumal Era Module-III Age of Naduvazhis ModuleIV Advent of Europeans Kerala Society And Culture:Ancient And Medieval Page 3 School of Distance Education Kerala Society And Culture:Ancient And Medieval Page 4 School of Distance Education Module-I Kerala’s Physiographical Features and Early History of the Region Geographical features Kerala has had the qualification of being an autonomous topographical and political element from the good old days. It’s one of a kind land position and unconventional physical elements have contributed Kerala with a particular singularity. The place where there is Kerala involves the slender waterfront strip limited by the Western Ghats on the east and the Arabian sea on the west in the southern part of the Indian subcontinent. Confusing as it may appear, this geological position has guaranteed, to some degree, its political and social disconnection from whatever remains of the nation furthermore encouraged its broad and dynamic contacts with the nations of the outside world.