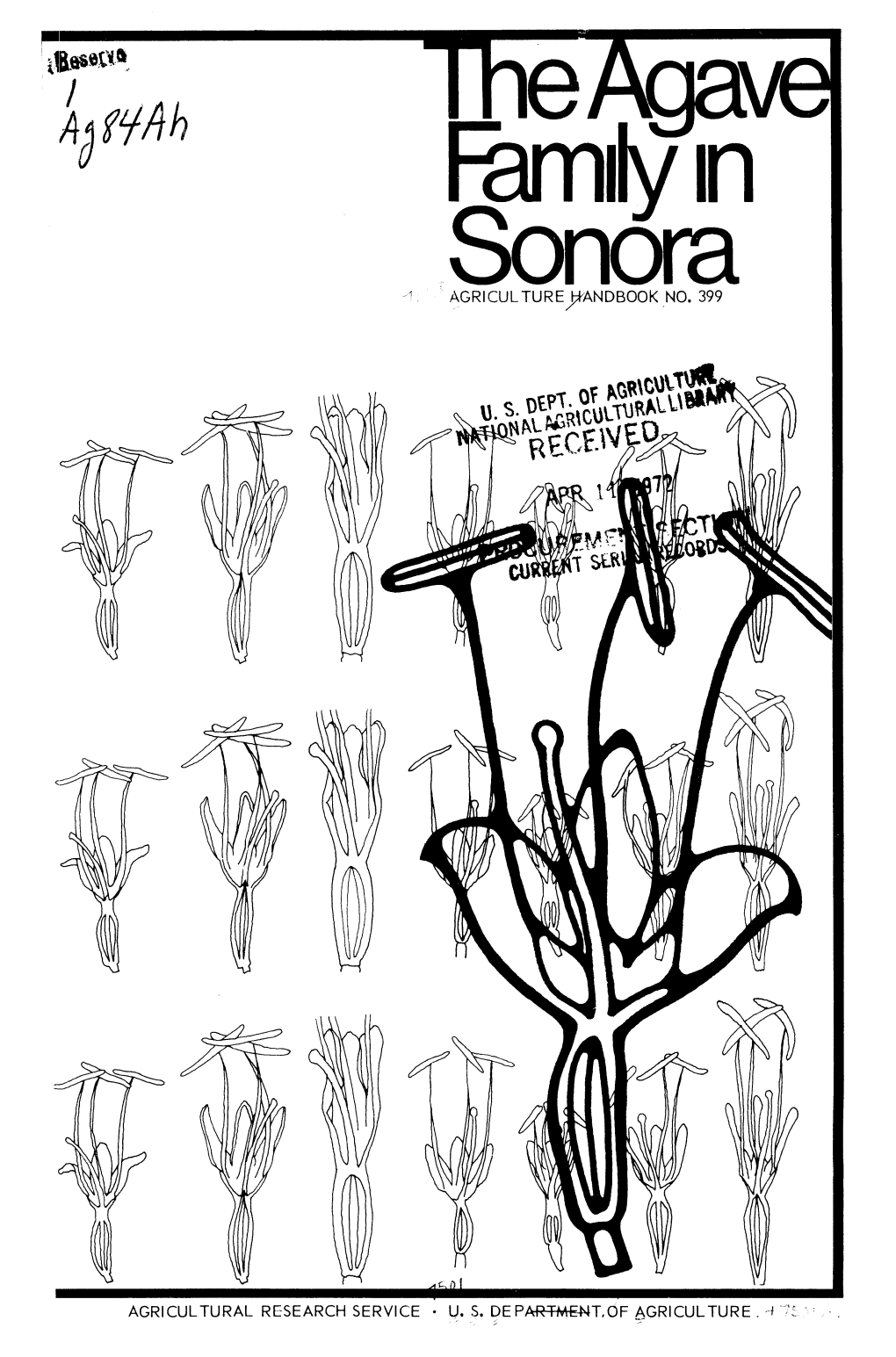

THE AGAVE FAMILY in SONORA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arizona Game and Fish Department Heritage Data Management System

ARIZONA GAME AND FISH DEPARTMENT HERITAGE DATA MANAGEMENT SYSTEM Plant Abstract Element Code: PMAGA010N2 Data Sensitivity: YES CLASSIFICATION, NOMENCLATURE, DESCRIPTION, RANGE NAME: Agave schottii var. treleasei (Toumey) Kearney & Peebles COMMON NAME: Trelease Agave, Schott Agave, Trelease Shindagger, Trelease’s century plant SYNONYMS: Agave treleasei Toumey FAMILY: Agavaceae AUTHOR, PLACE OF PUBLICATION: Agave schottii var. treleasei (Toumey) T.H. Kearney, and R.H. Peebles, Jour. Wash. Acad. Sciences 29(11): 474. 1939. Agave treleasei Toumey, Annual Rep. Missouri Bot. Gard. 12: 75-76, pl. 32-33. 1901. TYPE LOCALITY: USA: Arizona: Pima County: Castle Rock, SW slope of Santa Catalina Mt. TYPE SPECIMEN: HT: Toumey s.n. (“in herb. Toumey”); possibly IT at: ARIZ, MO, US. “Present location of specimen unknown” (Phillips and Hodgson 1991). What appears to be an isotype found at MO (Hodgson, 1995). TAXONOMIC UNIQUENESS: The variety treleasei is 1 of 2 in the species Agave schottii; the other is var. schottii. In North America, the species schottii is 1 of 34 in the genus Agave. There are more than 200 species recognized from the southern USA to northern South America, and throughout the Caribbean. The variety treleasei is very rare and poorly known. In the Santa Catalina Mountains, it is possibly a polyploid form of schottii, or another case of hybridization between A. chrysantha or A. palmeri and A. schottii var. schottii (Hodgson 1987 Pers. Comm.). Formerly, a population in the Ajo Mountains was thought to be a disjunct population of var. treleasi, but through genetic testing, it was determined to be of hybrid origin between Agave s. -

Publications by David Lack

Publications by David Lack Books 1934 The Birds of Cambridgeshire. Cambridge Bird Club, Cambridge. 1943 The Life of the Robin. Witherby, London. 4th edn. (revised) 1965. 1947 Darwin's Finches. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Harper Torch book paperback edn. 1961. Japanese edn. 1974. 1950 Robin Redbreast. Oxford University Press, Oxford. 1954 The Natural Regulation of Animal Numbers. Clarendon Press, Oxford. Paperback edn. 1970. Russian edn. 1957. 1956 Swifts in a Tower. Methuen, London. 1957 Evolutionary Theory and Christian Belief. Methuen, London. Reprinted with new chapter 1961. 1965 Enjoying Ornithology. Methuen, London. 1966 Population Studies of Birds. Clarendon Press, Oxford. 1968 Ecological Adaptations for Breeding in Birds. Methuen, London. 1971 Ecological Isolation in Birds. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford and Edinburgh. 1974 Evolution Illustrated by Waterfowl. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford and Edinburgh. 1976 Island Biology. fllustrated by the Land birds of Jamaica. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford and Edinburgh. Papers 1930 Double -brooding of the Nightjar. Br. Birds, 23, 242 - 244. 1930 Some diurnal observations on the Night jar. Land. Nat., 1930, pp. 47-55. 1930 Spring migration, 1930, at the Cambridge Sewage Farm. Br. Birds, 24, 145 -154. 1931 Coleoptera on St. Kilda in 1931.Entomologists' Monthly Mag., 47, 1 -4. 1931 Observations at sewage farms and reservoirs, 1930: Migration at Cambridge, autumn, 1930.Br. Birds, 24,280-282. 1932 Some breeding habits of the European Nightjar. Ibis, (13) 2, 266-284. 1932 Birds of Bear Island. Bull. Br. Omith. Qub, 53,64-69. 1932 With John Buchan and T. H. Harrisson. The early autumn migration at St. Kildain 193l.Scott.Nat., 1932,pp.1-8. -

2015 Annual Spring Meeting Macey Center New Mexico Tech Socorro, NM

New Mexico Geological Society Proceedings Volume 2015 Annual Spring Meeting Macey Center New Mexico Tech Socorro, NM NEW MEXICO GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2015 SPRING MEETING Friday, April 24, 2015 Macey Center NM Tech Campus Socorro, New Mexico 87801 NMGS EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE President: Mary Dowse Vice President: David Ennis Treasurer: Matthew Heizler Secretary: Susan Lucas Kamat Past President: Virginia McLemore 2015 SPRING MEETING COMMITTEE General Chair: Matthew Heizler Technical Program Chair: Peter Fawcett Registration Chair: Connie Apache ON-SITE REGISTRATION Connie Apache WEB SUPPORT Adam Read ORAL SESSION CHAIRS Peter Fawcett, Matt Zimmerer, Lewis Land, Spencer Lucas, Matt Heizler Session 1: Theme Session - Session 2: Volcanology and Paleoclimate: Is the Past the Key to Proterozoic Tectonics: the Future? Auditorium: 8:45 AM - 10:45 AM Galena Room: 8:45 AM - 10:45 AM Chair: Peter Fawcett Chair: Matthew Zimmerer GLOBAL ICE AGES, REGIONAL TECTONISM U-PB GEOCHRONOLOGY OF ASH FALL TUFFS AND LATE PALEOZOIC SEDIMENTATION IN IN THE MCRAE FORMATION (UPPER NEW MEXICO CRETACEOUS), SOUTH-CENTRAL NEW MEXICO — Spencer G. Lucas and Karl Krainer — Greg Mack, Jeffrey M. Amato, and Garland 8:45 AM - 9:00 AM R. Upchurch 8:45 AM - 9:00 AM URANIUM ISOTOPE EVIDENCE FOR PERVASIVE TIMING, GEOCHEMISTRY, AND DISTRIBUTION MARINE ANOXIA DURING THE LATE OF MAGMATISM IN THE RIO GRANDE RIFT ORDOVICIAN MASS EXTINCTION. — Rediet Abera, Brad Sion, Jolante van Wijk, — Rickey W Bartlett, Maya Elrick, Yemane Gary Axen, Dan Koning, Richard Chamberlin, Asmerom, Viorel Atudorei, and Victor Polyak Evan Gragg, Kyle Murray, and Jeff Dobbins 9:00 AM - 9:15 AM 9:00 AM - 9:15 AM FAUNAL AND FLORAL DYNAMICS DURING THE N-S EXTENSION AND BIMODAL MAGMATISM EARLY PALEOCENE: THE RECORD FROM THE DURING EARLY RIO GRANDE RIFTING: SAN JUAN BASIN, NEW MEXICO INSIGHTS FROM E-W STRIKING DIKES AT — Thomas E. -

Pima County Plant List (2020) Common Name Exotic? Source

Pima County Plant List (2020) Common Name Exotic? Source McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abies concolor var. concolor White fir Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abies lasiocarpa var. arizonica Corkbark fir Devender, T. R. (2005) Abronia villosa Hariy sand verbena McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abutilon abutiloides Shrubby Indian mallow Devender, T. R. (2005) Abutilon berlandieri Berlandier Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon incanum Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abutilon malacum Yellow Indian mallow Devender, T. R. (2005) Abutilon mollicomum Sonoran Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon palmeri Palmer Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon parishii Pima Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Abutilon parvulum Dwarf Indian mallow Herbarium; ASU Vascular Plant Herbarium Abutilon pringlei McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Abutilon reventum Yellow flower Indian mallow Herbarium; ASU Vascular Plant Herbarium McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia angustissima Whiteball acacia Devender, T. R. (2005); DBGH McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia constricta Whitethorn acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia greggii Catclaw acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) Acacia millefolia Santa Rita acacia McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia neovernicosa Chihuahuan whitethorn acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Acalypha lindheimeri Shrubby copperleaf Herbarium Acalypha neomexicana New Mexico copperleaf McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acalypha ostryaefolia McLaughlin, S. (1992) Acalypha pringlei McLaughlin, S. (1992) Acamptopappus McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Rayless goldenhead sphaerocephalus Herbarium Acer glabrum Douglas maple McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acer grandidentatum Sugar maple McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acer negundo Ashleaf maple McLaughlin, S. -

A Vegetation Map of Carlsbad Caverns National Park, New Mexico 1

______________________________________________________________________________ A Vegetation Map of Carlsbad Caverns National Park, New Mexico ______________________________________________________________________________ 2003 A Vegetation Map of Carlsbad Caverns National Park, New Mexico 1 Esteban Muldavin, Paul Neville, Paul Arbetan, Yvonne Chauvin, Amanda Browder, and Teri Neville2 ABSTRACT A vegetation classification and high resolution vegetation map was developed for Carlsbad Caverns National Park, New Mexico to support natural resources management, particularly fire management and rare species habitat analysis. The classification and map were based on 400 field plots collected between 1999 and 2002. The vegetation communities of Carlsbad Caverns NP are diverse. They range from desert shrublands and semi-grasslands of the lowland basins and foothills up through montane grasslands, shrublands, and woodlands of the highest elevations. Using various multivariate statistical tools, we identified 85 plant associations for the park, many of them unique in the Southwest. The vegetation map was developed using a combination of automated digital processing (supervised classifications) and direct image interpretation of high-resolution satellite imagery (Landsat Thematic Mapper and IKONOS). The map is composed of 34 map units derived from the vegetation classification, and is designed to facilitate ecologically based natural resources management at a 1:24,000 scale with 0.5 ha minimum map unit size (NPS national standard). Along with an overview of the vegetation ecology of the park in the context of the classification, descriptions of the composition and distribution of each map unit are provided. The map was delivered both in hard copy and in digital form as part of a geographic information system (GIS) compatible with that used in the park. -

An Ethnographicsurvey

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 186 Anthropological Papers, No. 65 THE WARIHIO INDIANS OF SONORA-CHIHUAHUA: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC SURVEY By Howard Scott Gentry 61 623-738—63- CONTENTS PAGE Preface 65 Introduction 69 Informants and acknowledgments 69 Nominal note 71 Peoples of the Rio Mayo and Warihio distribution 73 Habitat 78 Arroyos 78 Canyon features 79 Hills 79 Cliffs 80 Sierra features - 80 Plants utilized 82 Cultivated plants 82 Wild plants 89 Root and herbage foods 89 Seed foods 92 Fruits 94 Construction and fuel 96 Medicinal and miscellaneous uses 99 Use of animals 105 Domestic animals 105 Wild animals and methods of capture 106 Division of labor 108 Shelter 109 Granaries 110 Storage caves 111 Elevated structures 112 Substructures 112 Furnishings and tools 112 Handiwork 113 Pottery 113 The oUa 114 The small bowl 115 Firing 115 Weaving 115 Woodwork 116 Rope work 117 Petroglyphs 117 Transportation 118 Dress and ornament 119 Games 120 Social institutions 120 Marriage 120 The selyeme 121 Birth 122 Warihio names 123 Burial 124 63 64 CONTENTS PAGE Ceremony 125 Tuwuri 128 Pascola 131 The concluding ceremony 132 Myths 133 Creation myth 133 Myth of San Jose 134 The cross myth 134 Tales of his fathers 135 Fighting days 135 History of Tu\\njri 135 Songs of Juan Campa 136 Song of Emiliano Bourbon 136 Metamorphosis in animals 136 The Carbunco 136 Story of Juan Antonio Chapapoa 136 Social customs, ceremonial groups, and extraneous influences 137 Summary and conclusions 141 References cited 143 ILLUSTEATIONS PLATES (All plates follow p. 144) 28. a, Juan Campa and Warihio boy. -

Chromatid Abnormalities in Meiosis: a Brief Review and a Case Study in the Genus Agave (Asparagales, Asparagaceae)

Chapter 10 Chromatid Abnormalities in Meiosis: A Brief Review and a Case Study in the Genus Agave (Asparagales, Asparagaceae) Benjamín Rodríguez‐Garay Additional information is available at the end of the chapter http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.68974 Abstract The genus Agave is distributed in the tropical and subtropical areas of the world and represents a large group of succulent plants, with about 200 taxa from 136 species, and its center of origin is probably limited to Mexico. It is divided into two subgenera: Littaea and Agave based on the architecture of the inflorescence; the subgenus Littaea has a spicate or racemose inflorescence, while plants of the subgenus Agave have a paniculate inflorescence with flowers in umbellate clusters on lateral branches. As the main conclusion of this study, a hypothesis rises from the described observations: frying pan‐shaped chromosomes are formed by sister chromatid exchanges and a premature kinetochore movement in prophase II, which are meiotic aberrations that exist in these phylogenetic distant species, Agave stricta and A. angustifolia since ancient times in their evolution, and this may be due to genes that are prone to act under diverse kinds of environmental stress. Keywords: tequila, mescal, chromatid cohesion, centromere, inversion heterorozygosity, kinetochore 1. Introduction The genus Agave is distributed in the tropical and subtropical areas of the world and repre‐ sents a large group of succulent plants, with about 200 taxa from 136 species, and its center of origin is probably limited to Mexico [1]. It is divided into two subgenera: Littaea and Agave based on the architecture of the inflorescence; the subgenus Littaea has a spicate or racemose © 2017 The Author(s). -

PC23 Doc. 29.1 (Rev

Original language: English PC23 Doc. 29.1 (Rev. 1) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________ Twenty-third meeting of the Plants Committee Geneva (Switzerland), 22 and 24-27 July 2017 Species specific matters Maintenance of the Appendices Periodic review of species included in Appendices I and II OVERVIEW OF SPECIES UNDER PERIODIC REVIEW 1. This document has been prepared by the Secretariat. 2. In Resolution Conf. 14.8 (Rev. CoP17) on Periodic review of species included in Appendices I and II, the Conference of the Parties agrees on a process and guidelines for the Animals and Plants Committees to undertake a periodic review of animal or plant species included in the CITES Appendices and in paragraph 6: DIRECTS the Secretariat to maintain a record of species selected for periodic review, including: species previously and currently reviewed, dates of relevant Committee documents, recommendations from the reviews, and any reports and associated documents. 3. Annex 1 shows the record of plant species selected for review between the 13th and 15th meetings of the Conference of the Parties (CoP13, Bangkok, 2004; CoP15, Doha, 2010). 4. The record of plant species to be reviewed between CoP15 and the 17th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (CoP17, Johannesburg, 2016) is shown in Annex 2. 5. At its 21th meeting (PC21; Veracruz, May 2014), the Plants Committee reviewed records of species selected for periodic review and made several recommendations concerning species under review which are reflected in the tables shown in Annexes 1 and 2. 6. Annex 3 shows the List of abbreviations of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and Annex 4 presents the list of ISO country codes. -

Ajo Peak to Tinajas Altas: a Flora of Southwestern Arizona

Felger, R.S., S. Rutman, and J. Malusa. 2014. Ajo Peak to Tinajas Altas: A flora of southwestern Arizona. Part 6. Poaceae – grass family. Phytoneuron 2014-35: 1–139. Published 17 March 2014. ISSN 2153 733X AJO PEAK TO TINAJAS ALTAS: A FLORA OF SOUTHWESTERN ARIZONA Part 6. POACEAE – GRASS FAMILY RICHARD STEPHEN FELGER Herbarium, University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 & Sky Island Alliance P.O. Box 41165, Tucson, Arizona 85717 *Author for correspondence: [email protected] SUSAN RUTMAN 90 West 10th Street Ajo, Arizona 85321 JIM MALUSA School of Natural Resources and the Environment University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 [email protected] ABSTRACT A floristic account is provided for the grass family as part of the vascular plant flora of the contiguous protected areas of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, and the Tinajas Altas Region in southwestern Arizona. This is the second largest family in the flora area after Asteraceae. A total of 97 taxa in 46 genera of grasses are included in this publication, which includes ones established and reproducing in the modern flora (86 taxa in 43 genera), some occurring at the margins of the flora area or no long known from the area, and ice age fossils. At least 28 taxa are known by fossils recovered from packrat middens, five of which have not been found in the modern flora: little barley ( Hordeum pusillum ), cliff muhly ( Muhlenbergia polycaulis ), Paspalum sp., mutton bluegrass ( Poa fendleriana ), and bulb panic grass ( Zuloagaea bulbosa ). Non-native grasses are represented by 27 species, or 28% of the modern grass flora. -

Repertorium Plantarum Succulentarum LIV (2003) Repertorium Plantarum Succulentarum LIV (2003)

ISSN 0486-4271 IOS Repertorium Plantarum Succulentarum LIV (2003) Repertorium Plantarum Succulentarum LIV (2003) Index nominum novarum plantarum succulentarum anno MMIII editorum nec non bibliographia taxonomica ab U. Eggli et D. C. Zappi compositus. International Organization for Succulent Plant Study Internationale Organisation für Sukkulentenforschung December 2004 ISSN 0486-4271 Conventions used in Repertorium Plantarum Succulentarum — Repertorium Plantarum Succulentarum attempts to list, under separate headings, newly published names of succulent plants and relevant literature on the systematics of these plants, on an annual basis. New names noted after the issue for the relevant year has gone to press are included in later issues. Specialist periodical literature is scanned in full (as available at the libraries at ZSS and Z or received by the compilers). Also included is information supplied to the compilers direct. It is urgently requested that any reprints of papers not published in readily available botanical literature be sent to the compilers. — Validly published names are given in bold face type, accompanied by an indication of the nomenclatu- ral type (name or specimen dependent on rank), followed by the herbarium acronyms of the herbaria where the holotype and possible isotypes are said to be deposited (first acronym for holotype), accord- ing to Index Herbariorum, ed. 8 and supplements as published in Taxon. Invalid, illegitimate, or incor- rect names are given in italic type face. In either case a full bibliographic reference is given. For new combinations, the basionym is also listed. For invalid, illegitimate or incorrect names, the articles of the ICBN which have been contravened are indicated in brackets (note that the numbering of some regularly cited articles has changed in the Tokyo (1994) edition of ICBN). -

A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum Pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, Or Independent Domestication

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1v84t8z1 Journal KIVA, 83(4) ISSN 0023-1940 Authors Graham, AF Adams, KR Smith, SJ et al. Publication Date 2017-10-02 DOI 10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California KIVA Journal of Southwestern Anthropology and History ISSN: 0023-1940 (Print) 2051-6177 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ykiv20 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy To cite this article: Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy (2017): A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication, KIVA, DOI: 10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 View supplementary material Published online: 12 Oct 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ykiv20 Download by: [184.99.134.102] Date: 12 October 2017, At: 06:14 kiva, 2017, 1–29 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham1, Karen R. Adams2, Susan J. Smith3, and Terence M. -

Appendix B References

Final Tier 1 Environmental Impact Statement and Preliminary Section 4(f) Evaluation Appendix B, References July 2021 Federal Aid No. 999-M(161)S ADOT Project No. 999 SW 0 M5180 01P I-11 Corridor Final Tier 1 EIS Appendix B, References 1 This page intentionally left blank. July 2021 Project No. M5180 01P / Federal Aid No. 999-M(161)S I-11 Corridor Final Tier 1 EIS Appendix B, References 1 ADEQ. 2002. Groundwater Protection in Arizona: An Assessment of Groundwater Quality and 2 the Effectiveness of Groundwater Programs A.R.S. §49-249. Arizona Department of 3 Environmental Quality. 4 ADEQ. 2008. Ambient Groundwater Quality of the Pinal Active Management Area: A 2005-2006 5 Baseline Study. Open File Report 08-01. Arizona Department of Environmental Quality Water 6 Quality Division, Phoenix, Arizona. June 2008. 7 https://legacy.azdeq.gov/environ/water/assessment/download/pinal_ofr.pdf. 8 ADEQ. 2011. Arizona State Implementation Plan: Regional Haze Under Section 308 of the 9 Federal Regional Haze Rule. Air Quality Division, Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, 10 Phoenix, Arizona. January 2011. https://www.resolutionmineeis.us/documents/adeq-sip- 11 regional-haze-2011. 12 ADEQ. 2013a. Ambient Groundwater Quality of the Upper Hassayampa Basin: A 2003-2009 13 Baseline Study. Open File Report 13-03, Phoenix: Water Quality Division. 14 https://legacy.azdeq.gov/environ/water/assessment/download/upper_hassayampa.pdf. 15 ADEQ. 2013b. Arizona Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Fact Sheet: Construction 16 General Permit for Stormwater Discharges Associated with Construction Activity. Arizona 17 Department of Environmental Quality. June 3, 2013. 18 https://static.azdeq.gov/permits/azpdes/cgp_fact_sheet_2013.pdf.