Zealandia: Earth’S Hidden Continent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hikurangi Plateau: Crustal Structure, Rifted Formation, and Gondwana Subduction History

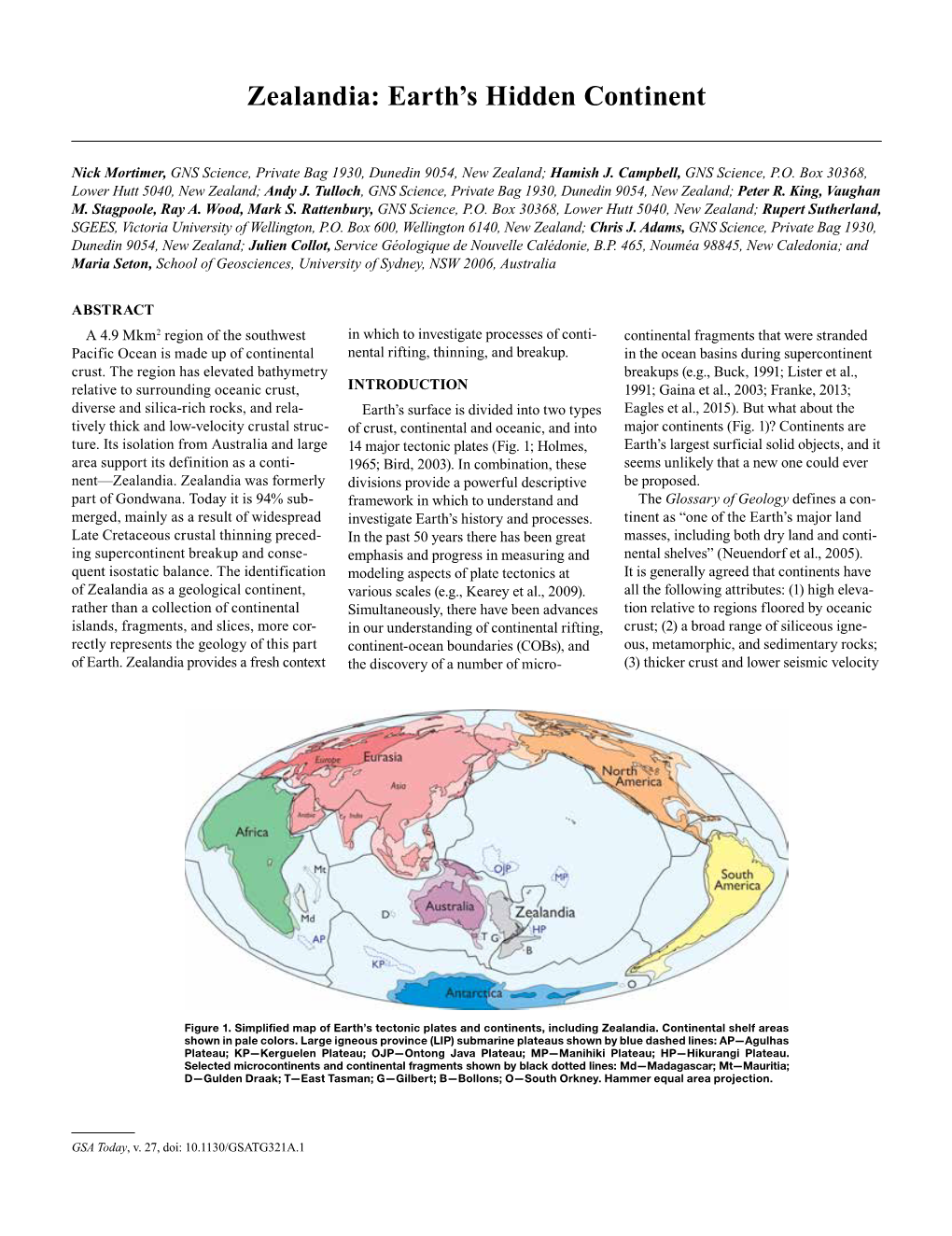

Article Geochemistry 3 Volume 9, Number 7 Geophysics 3 July 2008 Q07004, doi:10.1029/2007GC001855 GeosystemsG G ISSN: 1525-2027 AN ELECTRONIC JOURNAL OF THE EARTH SCIENCES Published by AGU and the Geochemical Society Click Here for Full Article Hikurangi Plateau: Crustal structure, rifted formation, and Gondwana subduction history Bryan Davy Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, P.O. Box 30368, Lower Hutt, New Zealand ([email protected]) Kaj Hoernle IFM-GEOMAR, Wischhofstraße 1-3, D-24148 Kiel, Germany Reinhard Werner Tethys Geoconsulting GmbH, Wischhofstraße 1-3, D-24148 Kiel, Germany [1] Seismic reflection profiles across the Hikurangi Plateau Large Igneous Province and adjacent margins reveal the faulted volcanic basement and overlying Mesozoic-Cenozoic sedimentary units as well as the structure of the paleoconvergent Gondwana margin at the southern plateau limit. The Hikurangi Plateau crust can be traced 50–100 km southward beneath the Chatham Rise where subduction cessation timing and geometry are interpreted to be variable along the margin. A model fit of the Hikurangi Plateau back against the Manihiki Plateau aligns the Manihiki Scarp with the eastern margin of the Rekohu Embayment. Extensional and rotated block faults which formed during the breakup of the combined Manihiki- Hikurangi plateau are interpreted in seismic sections of the Hikurangi Plateau basement. Guyots and ridge- like seamounts which are widely scattered across the Hikurangi Plateau are interpreted to have formed at 99–89 Ma immediately following Hikurangi Plateau jamming of the Gondwana convergent margin at 100 Ma. Volcanism from this period cannot be separately resolved in the seismic reflection data from basement volcanism; hence seamount formation during Manihiki-Hikurangi Plateau emplacement and breakup (125–120 Ma) cannot be ruled out. -

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Geologic Storage Formation Classification: Understanding Its Importance and Impacts on CCS Opportunities in the United States

BEST PRACTICES for: Geologic Storage Formation Classification: Understanding Its Importance and Impacts on CCS Opportunities in the United States First Edition Disclaimer This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference therein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed therein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. Cover Photos—Credits for images shown on the cover are noted with the corresponding figures within this document. Geologic Storage Formation Classification: Understanding Its Importance and Impacts on CCS Opportunities in the United States September 2010 National Energy Technology Laboratory www.netl.doe.gov DOE/NETL-2010/1420 Table of Contents Table of Contents 5 Table of Contents Executive Summary ____________________________________________________________________________ 10 1.0 Introduction and Background -

Two Contrasting Phanerozoic Orogenic Systems Revealed by Hafnium Isotope Data William J

ARTICLES PUBLISHED ONLINE: 17 APRIL 2011 | DOI: 10.1038/NGEO1127 Two contrasting Phanerozoic orogenic systems revealed by hafnium isotope data William J. Collins1*(, Elena A. Belousova2, Anthony I. S. Kemp1 and J. Brendan Murphy3 Two fundamentally different orogenic systems have existed on Earth throughout the Phanerozoic. Circum-Pacific accretionary orogens are the external orogenic system formed around the Pacific rim, where oceanic lithosphere semicontinuously subducts beneath continental lithosphere. In contrast, the internal orogenic system is found in Europe and Asia as the collage of collisional mountain belts, formed during the collision between continental crustal fragments. External orogenic systems form at the boundary of large underlying mantle convection cells, whereas internal orogens form within one supercell. Here we present a compilation of hafnium isotope data from zircon minerals collected from orogens worldwide. We find that the range of hafnium isotope signatures for the external orogenic system narrows and trends towards more radiogenic compositions since 550 Myr ago. By contrast, the range of signatures from the internal orogenic system broadens since 550 Myr ago. We suggest that for the external system, the lower crust and lithospheric mantle beneath the overriding continent is removed during subduction and replaced by newly formed crust, which generates the radiogenic hafnium signature when remelted. For the internal orogenic system, the lower crust and lithospheric mantle is instead eventually replaced by more continental lithosphere from a collided continental fragment. Our suggested model provides a simple basis for unravelling the global geodynamic evolution of the ancient Earth. resent-day orogens of contrasting character can be reduced to which probably began by the Early Ordovician12, and the Early two types on Earth, dominantly accretionary or dominantly Paleozoic accretionary orogens in the easternmost Altaids of Pcollisional, because only the latter are associated with Wilson Asia13. -

Playing Jigsaw with Large Igneous Provinces a Plate Tectonic

PUBLICATIONS Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems RESEARCH ARTICLE Playing jigsaw with Large Igneous Provinces—A plate tectonic 10.1002/2015GC006036 reconstruction of Ontong Java Nui, West Pacific Key Points: Katharina Hochmuth1, Karsten Gohl1, and Gabriele Uenzelmann-Neben1 New plate kinematic reconstruction of the western Pacific during the 1Alfred-Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum fur€ Polar- und Meeresforschung, Bremerhaven, Germany Cretaceous Detailed breakup scenario of the ‘‘Super’’-Large Igneous Province Abstract The three largest Large Igneous Provinces (LIP) of the western Pacific—Ontong Java, Manihiki, Ontong Java Nui Ontong Java Nui ‘‘Super’’-Large and Hikurangi Plateaus—were emplaced during the Cretaceous Normal Superchron and show strong simi- Igneous Province as result of larities in their geochemistry and petrology. The plate tectonic relationship between those LIPs, herein plume-ridge interaction referred to as Ontong Java Nui, is uncertain, but a joined emplacement was proposed by Taylor (2006). Since this hypothesis is still highly debated and struggles to explain features such as the strong differences Correspondence to: in crustal thickness between the different plateaus, we revisited the joined emplacement of Ontong Java K. Hochmuth, [email protected] Nui in light of new data from the Manihiki Plateau. By evaluating seismic refraction/wide-angle reflection data along with seismic reflection records of the margins of the proposed ‘‘Super’’-LIP, a detailed scenario Citation: for the emplacement and the initial phase of breakup has been developed. The LIP is a result of an interac- Hochmuth, K., K. Gohl, and tion of the arriving plume head with the Phoenix-Pacific spreading ridge in the Early Cretaceous. The G. -

Neoproterozoic Glaciations in a Revised Global Palaeogeography from the Breakup of Rodinia to the Assembly of Gondwanaland

Sedimentary Geology 294 (2013) 219–232 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Sedimentary Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/sedgeo Invited review Neoproterozoic glaciations in a revised global palaeogeography from the breakup of Rodinia to the assembly of Gondwanaland Zheng-Xiang Li a,b,⁎, David A.D. Evans b, Galen P. Halverson c,d a ARC Centre of Excellence for Core to Crust Fluid Systems (CCFS) and The Institute for Geoscience Research (TIGeR), Department of Applied Geology, Curtin University, GPO Box U1987, Perth, WA 6845, Australia b Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520-8109, USA c Earth & Planetary Sciences/GEOTOP, McGill University, 3450 University St., Montreal, Quebec H3A0E8, Canada d Tectonics, Resources and Exploration (TRaX), School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia article info abstract Article history: This review paper presents a set of revised global palaeogeographic maps for the 825–540 Ma interval using Received 6 January 2013 the latest palaeomagnetic data, along with lithological information for Neoproterozoic sedimentary basins. Received in revised form 24 May 2013 These maps form the basis for an examination of the relationships between known glacial deposits, Accepted 28 May 2013 palaeolatitude, positions of continental rifting, relative sea-level changes, and major global tectonic events Available online 5 June 2013 such as supercontinent assembly, breakup and superplume events. This analysis reveals several fundamental ’ Editor: J. Knight palaeogeographic features that will help inform and constrain models for Earth s climatic and geodynamic evolution during the Neoproterozoic. First, glacial deposits at or near sea level appear to extend from high Keywords: latitudes into the deep tropics for all three Neoproterozoic ice ages (Sturtian, Marinoan and Gaskiers), al- Neoproterozoic though the Gaskiers interval remains very poorly constrained in both palaeomagnetic data and global Rodinia lithostratigraphic correlations. -

Countries and Continents of the World: a Visual Model

Countries and Continents of the World http://geology.com/world/world-map-clickable.gif By STF Members at The Crossroads School Africa Second largest continent on earth (30,065,000 Sq. Km) Most countries of any other continent Home to The Sahara, the largest desert in the world and The Nile, the longest river in the world The Sahara: covers 4,619,260 km2 The Nile: 6695 kilometers long There are over 1000 languages spoken in Africa http://www.ecdc-cari.org/countries/Africa_Map.gif North America Third largest continent on earth (24,256,000 Sq. Km) Composed of 23 countries Most North Americans speak French, Spanish, and English Only continent that has every kind of climate http://www.freeusandworldmaps.com/html/WorldRegions/WorldRegions.html Asia Largest continent in size and population (44,579,000 Sq. Km) Contains 47 countries Contains the world’s largest country, Russia, and the most populous country, China The Great Wall of China is the only man made structure that can be seen from space Home to Mt. Everest (on the border of Tibet and Nepal), the highest point on earth Mt. Everest is 29,028 ft. (8,848 m) tall http://craigwsmall.wordpress.com/2008/11/10/asia/ Europe Second smallest continent in the world (9,938,000 Sq. Km) Home to the smallest country (Vatican City State) There are no deserts in Europe Contains mineral resources: coal, petroleum, natural gas, copper, lead, and tin http://www.knowledgerush.com/wiki_image/b/bf/Europe-large.png Oceania/Australia Smallest continent on earth (7,687,000 Sq. -

Proterozoic East Gondwana: Supercontinent Assembly and Breakup Geological Society Special Publications Society Book Editors R

Proterozoic East Gondwana: Supercontinent Assembly and Breakup Geological Society Special Publications Society Book Editors R. J. PANKHURST (CHIEF EDITOR) P. DOYLE E J. GREGORY J. S. GRIFFITHS A. J. HARTLEY R. E. HOLDSWORTH A. C. MORTON N. S. ROBINS M. S. STOKER J. P. TURNER Special Publication reviewing procedures The Society makes every effort to ensure that the scientific and production quality of its books matches that of its journals. Since 1997, all book proposals have been refereed by specialist reviewers as well as by the Society's Books Editorial Committee. If the referees identify weaknesses in the proposal, these must be addressed before the proposal is accepted. Once the book is accepted, the Society has a team of Book Editors (listed above) who ensure that the volume editors follow strict guidelines on refereeing and quality control. We insist that individual papers can only be accepted after satis- factory review by two independent referees. The questions on the review forms are similar to those for Journal of the Geological Society. The referees' forms and comments must be available to the Society's Book Editors on request. Although many of the books result from meetings, the editors are expected to commission papers that were not pre- sented at the meeting to ensure that the book provides a balanced coverage of the subject. Being accepted for presentation at the meeting does not guarantee inclusion in the book. Geological Society Special Publications are included in the ISI Science Citation Index, but they do not have an impact factor, the latter being applicable only to journals. -

Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems – Processes and Practices in the High Seas Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems Processes and Practices in the High Seas

ISSN 2070-7010 FAO 595 FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE TECHNICAL PAPER 595 Vulnerable marine ecosystems – Processes and practices in the high seas Vulnerable marine ecosystems Processes and practices in the high seas This publication, Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems: processes and practices in the high seas, provides regional fisheries management bodies, States, and other interested parties with a summary of existing regional measures to protect vulnerable marine ecosystems from significant adverse impacts caused by deep-sea fisheries using bottom contact gears in the high seas. This publication compiles and summarizes information on the processes and practices of the regional fishery management bodies, with mandates to manage deep-sea fisheries in the high seas, to protect vulnerable marine ecosystems. ISBN 978-92-5-109340-5 ISSN 2070-7010 FAO 9 789251 093405 I5952E/2/03.17 Cover photo credits: Photo descriptions clockwise from top-left: Acanthagorgia spp., Paragorgia arborea, Vase sponges (images courtesy of Fisheries and Oceans, Canada); and Callogorgia spp. (image courtesy of Kirsty Kemp, the Zoological Society of London). FAO FISHERIES AND Vulnerable marine ecosystems AQUACULTURE TECHNICAL Processes and practices in the high seas PAPER 595 Edited by Anthony Thompson FAO Consultant Rome, Italy Jessica Sanders Fisheries Officer FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Rome, Italy Merete Tandstad Fisheries Resources Officer FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Rome, Italy Fabio Carocci Fishery Information Assistant FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Rome, Italy and Jessica Fuller FAO Consultant Rome, Italy FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2016 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Geology and Mineral Resources of the Northern Territory

Geology and mineral resources of the Northern Territory Ahmad M and Munson TJ (compilers) Northern Territory Geological Survey Special Publication 5 Chapter 1: Introduction BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE: Ahmad M and Scrimgeour IR, 2013. Chapter 1: Introduction: in Ahmad M and Munson TJ (compilers). ‘Geology and mineral resources of the Northern Territory’. Northern Territory Geological Survey, Special Publication 5. Disclaimer While all care has been taken to ensure that information contained in this publication is true and correct at the time of publication, changes in circumstances after the time of publication may impact on the accuracy of its information. The Northern Territory of Australia gives no warranty or assurance, and makes no representation as to the accuracy of any information or advice contained in this publication, or that it is suitable for your intended use. You should not rely upon information in this publication for the purpose of making any serious business or investment decisions without obtaining independent and/or professional advice in relation to your particular situation. The Northern Territory of Australia disclaims any liability or responsibility or duty of care towards any person for loss or damage caused by any use of, or reliance on the information contained in this publication. Introduction Current as of January 2013 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION M Ahmad and IR Scrimgeour The Northern Territory of Australia covers an area of about Chapters 2 and 3 cover Territory-wide topics; they 1.35 million km 2 and comprises ninety 1:250 000-scale respectively describe the geological framework of the topographic mapsheets. First Edition geological mapping NT and summarise the major commodities. -

Campbell Plateau: a Major Control on the SW Pacific Sector of The

Ocean Sci. Discuss., doi:10.5194/os-2017-36, 2017 Manuscript under review for journal Ocean Sci. Discussion started: 15 May 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC-BY 3.0 License. Campbell Plateau: A major control on the SW Pacific sector of the Southern Ocean circulation. Aitana Forcén-Vázquez1,2, Michael J. M. Williams1, Melissa Bowen3, Lionel Carter2, and Helen Bostock1 1NIWA 2Victoria University of Wellington 3The University of Auckland Correspondence to: Aitana ([email protected]) Abstract. New Zealand’s subantarctic region is a dynamic oceanographic zone with the Subtropical Front (STF) to the north and the Subantarctic Front (SAF) to the south. Both the fronts and their associated currents are strongly influenced by topog- raphy: the South Island of New Zealand and the Chatham Rise for the STF, and Macquarie Ridge and Campbell Plateau for the SAF. Here for the first time we present a consistent picture across the subantarctic region of the relationships between front 5 positions, bathymetry and water mass structure using eight high resolution oceanographic sections that span the region. Our results show that the northwest side of Campbell Plateau is comparatively warm due to a southward extension of the STF over the plateau. The SAF is steered south and east by Macquarie Ridge and Campbell Plateau, with waters originating in the SAF also found north of the plateau in the Bounty Trough. Subantarctic Mode Water (SAMW) formation is confirmed to exist south of the plateau on the northern side of the SAF in winter, while on Campbell Plateau a deep reservoir persists into the following 10 autumn. -

Dynamic Subsidence of Eastern Australia During the Cretaceous

Gondwana Research 19 (2011) 372–383 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Gondwana Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gr Dynamic subsidence of Eastern Australia during the Cretaceous Kara J. Matthews a,⁎, Alina J. Hale a, Michael Gurnis b, R. Dietmar Müller a, Lydia DiCaprio a,c a EarthByte Group, School of Geosciences, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia b Seismological Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA c Now at: ExxonMobil Exploration Company, Houston, TX, USA article info abstract Article history: During the Early Cretaceous Australia's eastward passage over sinking subducted slabs induced widespread Received 16 February 2010 dynamic subsidence and formation of a large epeiric sea in the eastern interior. Despite evidence for Received in revised form 25 June 2010 convergence between Australia and the paleo-Pacific, the subduction zone location has been poorly Accepted 28 June 2010 constrained. Using coupled plate tectonic–mantle convection models, we test two end-member scenarios, Available online 13 July 2010 one with subduction directly east of Australia's reconstructed continental margin, and a second with subduction translated ~1000 km east, implying the existence of a back-arc basin. Our models incorporate a Keywords: Geodynamic modelling rheological model for the mantle and lithosphere, plate motions since 140 Ma and evolving plate boundaries. Subduction While mantle rheology affects the magnitude of surface vertical motions, timing of uplift and subsidence Australia depends on plate boundary geometries and kinematics. Computations with a proximal subduction zone Cretaceous result in accelerated basin subsidence occurring 20 Myr too early compared with tectonic subsidence Tectonic subsidence calculated from well data.