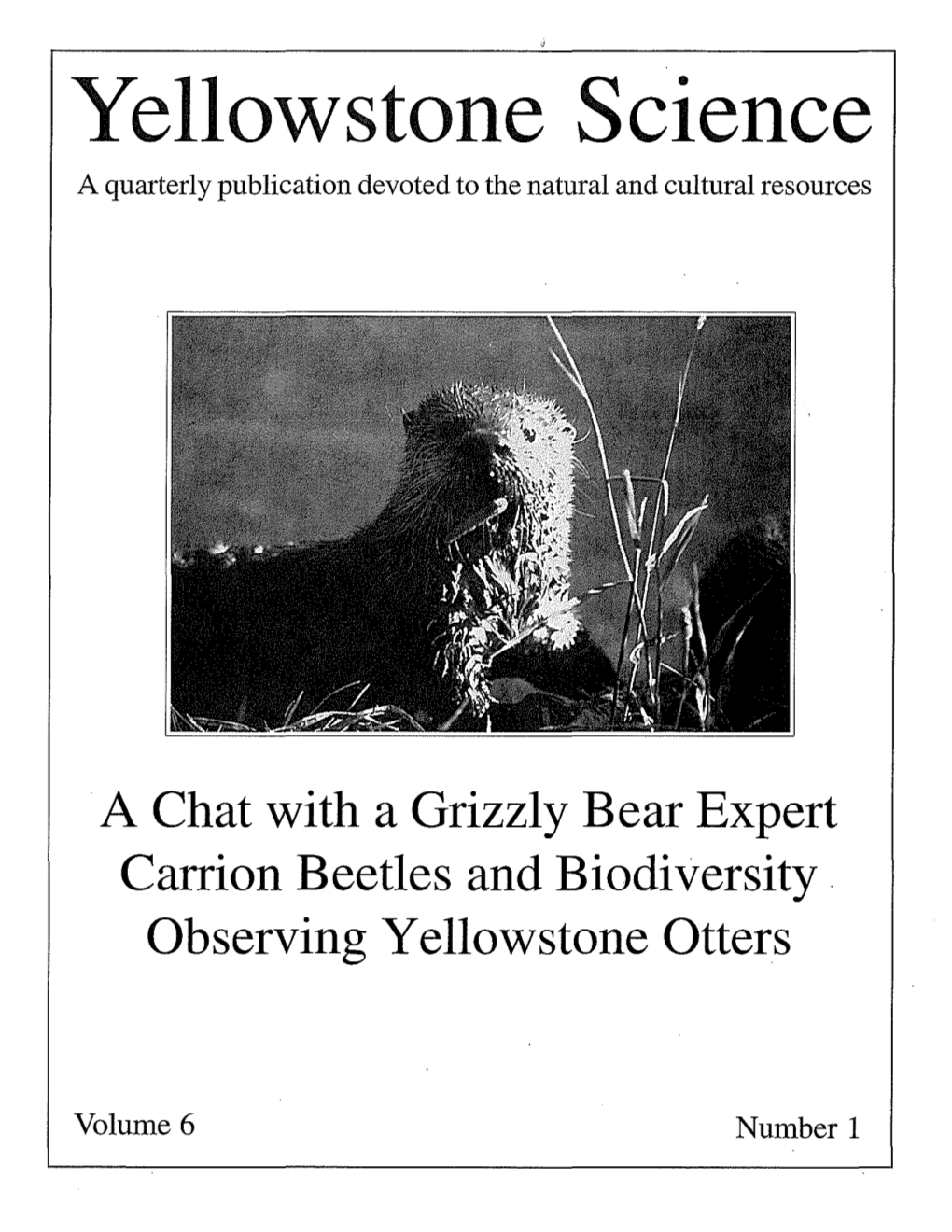

Yellowstone Science a Quarterly Publication Devoted to the Natural and Cultural Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Catalogue of Coleoptera Specimens with Potential Forensic Interest in the Goulandris Natural History Museum Collection

ENTOMOLOGIA HELLENICA Vol. 25, 2016 A catalogue of Coleoptera specimens with potential forensic interest in the Goulandris Natural History Museum collection Dimaki Maria Goulandris Natural History Museum, 100 Othonos St. 14562 Kifissia, Greece Anagnou-Veroniki Maria Makariou 13, 15343 Aghia Paraskevi (Athens), Greece Tylianakis Jason Zoology Department, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch, New Zealand http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/eh.11549 Copyright © 2017 Maria Dimaki, Maria Anagnou- Veroniki, Jason Tylianakis To cite this article: Dimaki, M., Anagnou-Veroniki, M., & Tylianakis, J. (2016). A catalogue of Coleoptera specimens with potential forensic interest in the Goulandris Natural History Museum collection. ENTOMOLOGIA HELLENICA, 25(2), 31-38. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/eh.11549 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 27/12/2018 06:22:38 | ENTOMOLOGIA HELLENICA 25 (2016): 31-38 Received 15 March 2016 Accepted 12 December 2016 Available online 3 February 2017 A catalogue of Coleoptera specimens with potential forensic interest in the Goulandris Natural History Museum collection MARIA DIMAKI1’*, MARIA ANAGNOU-VERONIKI2 AND JASON TYLIANAKIS3 1Goulandris Natural History Museum, 100 Othonos St. 14562 Kifissia, Greece 2Makariou 13, 15343 Aghia Paraskevi (Athens), Greece 3Zoology Department, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch, New Zealand ABSTRACT This paper presents a catalogue of the Coleoptera specimens in the Goulandris Natural History Museum collection that have potential forensic interest. Forensic entomology can help to estimate the time elapsed since death by studying the necrophagous insects collected on a cadaver and its surroundings. In this paper forty eight species (369 specimens) are listed that belong to seven families: Silphidae (3 species), Staphylinidae (6 species), Histeridae (11 species), Anobiidae (4 species), Cleridae (6 species), Dermestidae (14 species), and Nitidulidae (4 species). -

Coleoptera Species of Forensic Importance from Brazil: an Updated List

G Model RBE-49; No. of Pages 11 ARTICLE IN PRESS Revista Brasileira de Entomologia xxx (2015) xxx–xxx REVISTA BRASILEIRA DE Entomologia A Journal on Insect Diversity and Evolution w ww.rbentomologia.com Systematics, Morphology and Biogeography Coleoptera species of forensic importance from Brazil: an updated list a,∗ a b Lúcia Massutti de Almeida , Rodrigo César Corrêa , Paschoal Coelho Grossi a Laboratório de Sistemática e Bioecologia de Coleoptera, Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil b Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Recife, PE, Brazil a b s t r a c t a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: A list of the Coleoptera of importance from Brazil, based on published records was compiled. The checklist Received 21 May 2015 contains 345 species of 16 families allocated to 16 states of the country. In addition, three species of two Accepted 14 August 2015 families are registered for the first time. The fauna of Coleoptera of forensic importance is still not entirely Available online xxx known and future collection efforts and taxonomic reviews could increase the number of known species Associate Editor: Rodrigo Krüger considerably in the near future. © 2015 Published by Elsevier Editora Ltda. on behalf of Sociedade Brasileira de Entomologia. This is an Keywords: Beetles open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license Cleridae (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Dermestidae Forensic entomology Silphidae Introduction behaviour are needed before their importance can be fully under- stood (see Midgley et al., 2010). The diversity of Coleoptera and The development of forensic entomology in Brazil was well the lack of taxonomic studies have direct effect in how the beetles reported by Pujol-Luz et al. -

Insecta: Coleoptera: Leiodidae: Cholevinae), with a Description of Sciaphyes Shestakovi Sp.N

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Arthropod Systematics and Phylogeny Jahr/Year: 2011 Band/Volume: 69 Autor(en)/Author(s): Fresneda Javier, Grebennikov Vasily V., Ribera Ignacio Artikel/Article: The phylogenetic and geographic limits of Leptodirini (Insecta: Coleoptera: Leiodidae: Cholevinae), with a description of Sciaphyes shestakovi sp.n. from the Russian Far East 99-123 Arthropod Systematics & Phylogeny 99 69 (2) 99 –123 © Museum für Tierkunde Dresden, eISSN 1864-8312, 21.07.2011 The phylogenetic and geographic limits of Leptodirini (Insecta: Coleoptera: Leiodidae: Cholevinae), with a description of Sciaphyes shestakovi sp. n. from the Russian Far East JAVIER FRESNEDA 1, 2, VASILY V. GREBENNIKOV 3 & IGNACIO RIBERA 4, * 1 Ca de Massa, 25526 Llesp, Lleida, Spain 2 Museu de Ciències Naturals (Zoologia), Passeig Picasso s/n, 08003 Barcelona, Spain [[email protected]] 3 Ottawa Plant Laboratory, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 960 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0C6, Canada [[email protected]] 4 Institut de Biologia Evolutiva (CSIC-UPF), Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta, 37 – 49, 08003 Barcelona, Spain [[email protected]] * Corresponding author Received 26.iv.2011, accepted 27.v.2011. Published online at www.arthropod-systematics.de on 21.vii.2011. > Abstract The tribe Leptodirini of the beetle family Leiodidae is one of the most diverse radiations of cave animals, with a distribution centred north of the Mediterranean basin from the Iberian Peninsula to Iran. Six genera outside this core area, most notably Platycholeus Horn, 1880 in the western United States and others in East Asia, have been assumed to be related to Lepto- dirini. -

Local and Landscape Effects on Carrion-Associated Rove Beetle (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae) Communities in German Forests

insects Article Local and Landscape Effects on Carrion-Associated Rove Beetle (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae) Communities in German Forests Sandra Weithmann 1,* , Jonas Kuppler 1 , Gregor Degasperi 2, Sandra Steiger 3 , Manfred Ayasse 1 and Christian von Hoermann 4 1 Institute of Evolutionary Ecology and Conservation Genomics, University of Ulm, 89069 Ulm, Germany; [email protected] (J.K.); [email protected] (M.A.) 2 Richard-Wagnerstraße 9, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] 3 Department of Evolutionary Animal Ecology, University of Bayreuth, 95447 Bayreuth, Germany; [email protected] 4 Department of Conservation and Research, Bavarian Forest National Park, 94481 Grafenau, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 21 November 2020; Published: 24 November 2020 Simple Summary: Increasing forest management practices by humans are threatening inherent insect biodiversity and thus important ecosystem services provided by them. One insect group which reacts sensitively to habitat changes are the rove beetles contributing to the maintenance of an undisturbed insect succession during decomposition by mainly hunting fly maggots. However, little is known about carrion-associated rove beetles due to poor taxonomic knowledge. In our study, we unveiled the human-induced and environmental drivers that modify rove beetle communities on vertebrate cadavers. At German forest sites selected by a gradient of management intensity, we contributed to the understanding of the rove beetle-mediated decomposition process. One main result is that an increasing human impact in forests changes rove beetle communities by promoting generalist and more open-habitat species coping with low structural heterogeneity, whereas species like Philonthus decorus get lost. -

The Beetle Fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and Distribution

INSECTA MUNDI, Vol. 20, No. 3-4, September-December, 2006 165 The beetle fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and distribution Stewart B. Peck Department of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6, Canada stewart_peck@carleton. ca Abstract. The beetle fauna of the island of Dominica is summarized. It is presently known to contain 269 genera, and 361 species (in 42 families), of which 347 are named at a species level. Of these, 62 species are endemic to the island. The other naturally occurring species number 262, and another 23 species are of such wide distribution that they have probably been accidentally introduced and distributed, at least in part, by human activities. Undoubtedly, the actual numbers of species on Dominica are many times higher than now reported. This highlights the poor level of knowledge of the beetles of Dominica and the Lesser Antilles in general. Of the species known to occur elsewhere, the largest numbers are shared with neighboring Guadeloupe (201), and then with South America (126), Puerto Rico (113), Cuba (107), and Mexico-Central America (108). The Antillean island chain probably represents the main avenue of natural overwater dispersal via intermediate stepping-stone islands. The distributional patterns of the species shared with Dominica and elsewhere in the Caribbean suggest stages in a dynamic taxon cycle of species origin, range expansion, distribution contraction, and re-speciation. Introduction windward (eastern) side (with an average of 250 mm of rain annually). Rainfall is heavy and varies season- The islands of the West Indies are increasingly ally, with the dry season from mid-January to mid- recognized as a hotspot for species biodiversity June and the rainy season from mid-June to mid- (Myers et al. -

A Baseline Invertebrate Survey of the Knepp Estate - 2015

A baseline invertebrate survey of the Knepp Estate - 2015 Graeme Lyons May 2016 1 Contents Page Summary...................................................................................... 3 Introduction.................................................................................. 5 Methodologies............................................................................... 15 Results....................................................................................... 17 Conclusions................................................................................... 44 Management recommendations........................................................... 51 References & bibliography................................................................. 53 Acknowledgements.......................................................................... 55 Appendices.................................................................................... 55 Front cover: One of the southern fields showing dominance by Common Fleabane. 2 0 – Summary The Knepp Wildlands Project is a large rewilding project where natural processes predominate. Large grazing herbivores drive the ecology of the site and can have a profound impact on invertebrates, both positive and negative. This survey was commissioned in order to assess the site’s invertebrate assemblage in a standardised and repeatable way both internally between fields and sections and temporally between years. Eight fields were selected across the estate with two in the north, two in the central block -

Midsouth Entomologist 5: 39-53 ISSN: 1936-6019

Midsouth Entomologist 5: 39-53 ISSN: 1936-6019 www.midsouthentomologist.org.msstate.edu Research Article Insect Succession on Pig Carrion in North-Central Mississippi J. Goddard,1* D. Fleming,2 J. L. Seltzer,3 S. Anderson,4 C. Chesnut,5 M. Cook,6 E. L. Davis,7 B. Lyle,8 S. Miller,9 E.A. Sansevere,10 and W. Schubert11 1Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, Entomology, and Plant Pathology, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, MS 39762, e-mail: [email protected] 2-11Students of EPP 4990/6990, “Forensic Entomology,” Mississippi State University, Spring 2012. 2272 Pellum Rd., Starkville, MS 39759, [email protected] 33636 Blackjack Rd., Starkville, MS 39759, [email protected] 4673 Conehatta St., Marion, MS 39342, [email protected] 52358 Hwy 182 West, Starkville, MS 39759, [email protected] 6101 Sandalwood Dr., Madison, MS 39110, [email protected] 72809 Hwy 80 East, Vicksburg, MS 39180, [email protected] 850102 Jonesboro Rd., Aberdeen, MS 39730, [email protected] 91067 Old West Point Rd., Starkville, MS 39759, [email protected] 10559 Sabine St., Memphis, TN 38117, [email protected] 11221 Oakwood Dr., Byhalia, MS 38611, [email protected] Received: 17-V-2012 Accepted: 16-VII-2012 Abstract: A freshly-euthanized 90 kg Yucatan mini pig, Sus scrofa domesticus, was placed outdoors on 21March 2012, at the Mississippi State University South Farm and two teams of students from the Forensic Entomology class were assigned to take daily (weekends excluded) environmental measurements and insect collections at each stage of decomposition until the end of the semester (42 days). Assessment of data from the pig revealed a successional pattern similar to that previously published – fresh, bloat, active decay, and advanced decay stages (the pig specimen never fully entered a dry stage before the semester ended). -

Yellowstone Science Volume 6, Number 1

Yellowstone Science A quarterly publication devoted to the natural and cultural resources ·A Chat with a Grizzly Bear Expert Carrion Beetles and Biodiversity. Observing Yellowstone Otters Volume 6 Number I The Legacy of Research As we begin a new year for Yellowstone But scientific understanding comes big and small. Studies ofnon-charismatic Science (the journal and, more important, slowly, often with p_ainstaking effort. creatures and features are as vital to our the program), we might consider the As a graduate student I was cautioned understanding the ecosystem as those of value of the varied research undertaken that my goal should not be to save the megafauna. in and around the park. It is popular in world with my research, but to contrib For 24 years, Dick Knight studied some circles to criticize the money we ute a small piece of knowledge from a one ofYellowstone's most famous and our society, not just the National Park Ser particular time and place to just one dis controversial species. With ?, bluntness vice-spend on science. Even many of cipline. I recalled this advice as I spoke atypical of most government bureau us who work within a scientific discipline with Nathan Varley, who in this issue crats, he answered much of what we admit that the ever-present "we need shares results of his work on river otters, demanded to know about grizzly bears, more data" can be both a truthful state about his worry that he could not defini never seeking the mantel of fame or ment and an excuse for not taking a stand. -

Staphylinidae (Coleoptera) Associated to Cattle Dung in Campo Grande, MS, Brazil

October - December 2002 641 SCIENTIFIC NOTE Staphylinidae (Coleoptera) Associated to Cattle Dung in Campo Grande, MS, Brazil WILSON W. K OLLER1,2, ALBERTO GOMES1, SÉRGIO R. RODRIGUES3 AND JÚLIO MENDES 4 1Embrapa Gado de Corte, C. postal 154, CEP 79002-970, Campo Grande, MS 2 [email protected] 3Universidade Estadual de Mato Grosso do Sul - UEMS, Aquidauana, MS 4Universidade Federal de Uberlândia - UFU, Uberlândia, MG Neotropical Entomology 31(4):641-645 (2002) Staphylinidae (Coleoptera) Associados a Fezes Bovinas em Campo Grande, MS RESUMO - Este trabalho foi executado com o objetivo de determinar as espécies locais de estafilinídeos fimícolas, devido à importância destes predadores e ou parasitóides no controle natural de parasitos de bovinos associadas às fezes. Para tanto, massas fecais com 1, 2 e 3 dias de idade foram coletadas semanalmente em uma pastagem de Brachiaria decumbens Stapf, no período de maio de 1990 a abril de 1992. As fezes foram acondicionadas em baldes plásticos, opacos, com capacidade para 15 litros, contendo aberturas lateral e no topo, onde foram fixados frascos para a captura, por um período de 40 dias, dos besouros estafilinídeos presentes nas massas fecais. Após este período a massa fecal e o solo existente nos baldes eram examinados e os insetos remanescentes recolhidos. Foi coletado um total de 13.215 exemplares, pertencendo a 34 espécies e/ou morfo espécies. Foram observados os seguintes doze gêneros: Oxytelus (3 espécies; 70,1%); Falagria (1 sp.; 7,9); Aleochara (4 sp.; 5,8); Philonthus (3 sp.; 5,1); Atheta (2 sp.; 4,0); Cilea (2 sp.; 1,2); Neohypnus (1 sp.; 0,7); Lithocharis (1 sp.; 0,7); Heterothops (2 sp.; 0,6); Somoleptus (1 sp.; 0,08); Dibelonetes (1 sp.; 0,06) e, Dysanellus (1 sp.; 0,04). -

Deadwood and Saproxylic Beetle Diversity in Naturally Disturbed and Managed Spruce Forests in Nova Scotia

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeysDeadwood 22: 309–340 and (2009) saproxylic beetle diversity in disturbed and managed spruce forests in Nova Scotia 309 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.22.144 RESEARCH ARTICLE www.pensoftonline.net/zookeys Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Deadwood and saproxylic beetle diversity in naturally disturbed and managed spruce forests in Nova Scotia DeLancey J. Bishop1,4, Christopher G. Majka2, Søren Bondrup-Nielsen3, Stewart B. Peck1 1 Department of Biology, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada 2 c/o Nova Scotia Museum, 1747 Summer St., Halifax, Nova Scotia Canada 3 Department of Biology, Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia, Canada 4 RR 5, Canning, Nova Scotia, Canada Corresponding author: Christopher G. Majka ([email protected]) Academic editor: Jan Klimaszewski | Received 26 March 2009 | Accepted 6 April 2009 | Published 28 September 2009 Citation: Bishop DJ, Majka CG, Bondrup-Nielsen S, Peck SB (2009) Deadwood and saproxylic beetle diversity in naturally disturbed and managed spruce forests in Nova Scotia In: Majka CG, Klimaszewski J (Eds) Biodiversity, Bio- systematics, and Ecology of Canadian Coleoptera II. ZooKeys 22: 309–340. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.22.144 Abstract Even-age industrial forestry practices may alter communities of native species. Th us, identifying coarse patterns of species diversity in industrial forests and understanding how and why these patterns diff er from those in naturally disturbed forests can play an essential role in attempts to modify forestry practices to minimize their impacts on native species. Th is study compares diversity patterns of deadwood habitat structure and saproxylic beetle species in spruce forests with natural disturbance histories (wind and fi re) and human disturbance histories (clearcutting and clearcutting with thinning). -

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, Version 2018-07-24

Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Species List, version 2018-07-24 Kenai National Wildlife Refuge biology staff July 24, 2018 2 Cover image: map of 16,213 georeferenced occurrence records included in the checklist. Contents Contents 3 Introduction 5 Purpose............................................................ 5 About the list......................................................... 5 Acknowledgments....................................................... 5 Native species 7 Vertebrates .......................................................... 7 Invertebrates ......................................................... 55 Vascular Plants........................................................ 91 Bryophytes ..........................................................164 Other Plants .........................................................171 Chromista...........................................................171 Fungi .............................................................173 Protozoans ..........................................................186 Non-native species 187 Vertebrates ..........................................................187 Invertebrates .........................................................187 Vascular Plants........................................................190 Extirpated species 207 Vertebrates ..........................................................207 Vascular Plants........................................................207 Change log 211 References 213 Index 215 3 Introduction Purpose to avoid implying -

Insects and Related Arthropods Associated with of Agriculture

USDA United States Department Insects and Related Arthropods Associated with of Agriculture Forest Service Greenleaf Manzanita in Montane Chaparral Pacific Southwest Communities of Northeastern California Research Station General Technical Report Michael A. Valenti George T. Ferrell Alan A. Berryman PSW-GTR- 167 Publisher: Pacific Southwest Research Station Albany, California Forest Service Mailing address: U.S. Department of Agriculture PO Box 245, Berkeley CA 9470 1 -0245 Abstract Valenti, Michael A.; Ferrell, George T.; Berryman, Alan A. 1997. Insects and related arthropods associated with greenleaf manzanita in montane chaparral communities of northeastern California. Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-167. Albany, CA: Pacific Southwest Research Station, Forest Service, U.S. Dept. Agriculture; 26 p. September 1997 Specimens representing 19 orders and 169 arthropod families (mostly insects) were collected from greenleaf manzanita brushfields in northeastern California and identified to species whenever possible. More than500 taxa below the family level wereinventoried, and each listing includes relative frequency of encounter, life stages collected, and dominant role in the greenleaf manzanita community. Specific host relationships are included for some predators and parasitoids. Herbivores, predators, and parasitoids comprised the majority (80 percent) of identified insects and related taxa. Retrieval Terms: Arctostaphylos patula, arthropods, California, insects, manzanita The Authors Michael A. Valenti is Forest Health Specialist, Delaware Department of Agriculture, 2320 S. DuPont Hwy, Dover, DE 19901-5515. George T. Ferrell is a retired Research Entomologist, Pacific Southwest Research Station, 2400 Washington Ave., Redding, CA 96001. Alan A. Berryman is Professor of Entomology, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-6382. All photographs were taken by Michael A. Valenti, except for Figure 2, which was taken by Amy H.