Midsouth Entomologist 5: 39-53 ISSN: 1936-6019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information Sheet Flightless Carcass Beetles

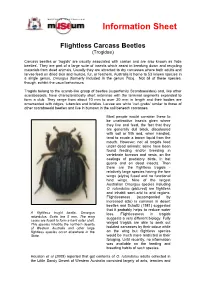

Information Sheet Flightless Carcass Beetles (Trogidae) Carcass beetles or ‘trogids’ are usually associated with carrion and are also known as ‘hide beetles’. They are part of a large suite of insects which assist in breaking down and recycling materials from dead animals. Usually they are attracted to dry carcasses where both adults and larvae feed on dried skin and muscle, fur, or feathers. Australia is home to 53 known species in a single genus, Omorgus (formerly included in the genus Trox). Not all of these species, though, exhibit the usual behaviours. Trogids belong to the scarablike group of beetles (superfamily Scarabaeoidea) and, like other scarabaeoids, have characteristically short antennae with the terminal segments expanded to form a club. They range from about 10 mm to over 30 mm in length and their bodies are ornamented with ridges, tubercles and bristles. Larvae are white ‘curlgrubs’ similar to those of other scarabaeoid beetles and live in burrows in the soil beneath carcasses. Most people would consider these to be unattractive insects given where they live and feed, the fact that they are generally dull black, discoloured with soil or filth and, when handled, tend to exude a brown liquid from the mouth. However, not all trogids feed under dead animals: some have been found feeding and/or breeding in vertebrate burrows and nests, on the castings of predatory birds, in bat guano and on dead insects. Then there are the flightless trogids relatively large species having the fore wings (elytra) fused and no functional hind wings. Nine of the largest Australian Omorgus species including O. -

Beetle Appreciation Diversity and Classification of Common Beetle Families Christopher E

Beetle Appreciation Diversity and Classification of Common Beetle Families Christopher E. Carlton Louisiana State Arthropod Museum Coleoptera Families Everyone Should Know (Checklist) Suborder Adephaga Suborder Polyphaga, cont. •Carabidae Superfamily Scarabaeoidea •Dytiscidae •Lucanidae •Gyrinidae •Passalidae Suborder Polyphaga •Scarabaeidae Superfamily Staphylinoidea Superfamily Buprestoidea •Ptiliidae •Buprestidae •Silphidae Superfamily Byrroidea •Staphylinidae •Heteroceridae Superfamily Hydrophiloidea •Dryopidae •Hydrophilidae •Elmidae •Histeridae Superfamily Elateroidea •Elateridae Coleoptera Families Everyone Should Know (Checklist, cont.) Suborder Polyphaga, cont. Suborder Polyphaga, cont. Superfamily Cantharoidea Superfamily Cucujoidea •Lycidae •Nitidulidae •Cantharidae •Silvanidae •Lampyridae •Cucujidae Superfamily Bostrichoidea •Erotylidae •Dermestidae •Coccinellidae Bostrichidae Superfamily Tenebrionoidea •Anobiidae •Tenebrionidae Superfamily Cleroidea •Mordellidae •Cleridae •Meloidae •Anthicidae Coleoptera Families Everyone Should Know (Checklist, cont.) Suborder Polyphaga, cont. Superfamily Chrysomeloidea •Chrysomelidae •Cerambycidae Superfamily Curculionoidea •Brentidae •Curculionidae Total: 35 families of 131 in the U.S. Suborder Adephaga Family Carabidae “Ground and Tiger Beetles” Terrestrial predators or herbivores (few). 2600 N. A. spp. Suborder Adephaga Family Dytiscidae “Predacious diving beetles” Adults and larvae aquatic predators. 500 N. A. spp. Suborder Adephaga Family Gyrindae “Whirligig beetles” Aquatic, on water -

10 Arthropods and Corpses

Arthropods and Corpses 207 10 Arthropods and Corpses Mark Benecke, PhD CONTENTS INTRODUCTION HISTORY AND EARLY CASEWORK WOUND ARTIFACTS AND UNUSUAL FINDINGS EXEMPLARY CASES: NEGLECT OF ELDERLY PERSONS AND CHILDREN COLLECTION OF ARTHROPOD EVIDENCE DNA FORENSIC ENTOMOTOXICOLOGY FURTHER ARTIFACTS CAUSED BY ARTHROPODS REFERENCES SUMMARY The determination of the colonization interval of a corpse (“postmortem interval”) has been the major topic of forensic entomologists since the 19th century. The method is based on the link of developmental stages of arthropods, especially of blowfly larvae, to their age. The major advantage against the standard methods for the determination of the early postmortem interval (by the classical forensic pathological methods such as body temperature, post- mortem lividity and rigidity, and chemical investigations) is that arthropods can represent an accurate measure even in later stages of the postmortem in- terval when the classical forensic pathological methods fail. Apart from esti- mating the colonization interval, there are numerous other ways to use From: Forensic Pathology Reviews, Vol. 2 Edited by: M. Tsokos © Humana Press Inc., Totowa, NJ 207 208 Benecke arthropods as forensic evidence. Recently, artifacts produced by arthropods as well as the proof of neglect of elderly persons and children have become a special focus of interest. This chapter deals with the broad range of possible applications of entomology, including case examples and practical guidelines that relate to history, classical applications, DNA typing, blood-spatter arti- facts, estimation of the postmortem interval, cases of neglect, and entomotoxicology. Special reference is given to different arthropod species as an investigative and criminalistic tool. Key Words: Arthropod evidence; forensic science; blowflies; beetles; colonization interval; postmortem interval; neglect of the elderly; neglect of children; decomposition; DNA typing; entomotoxicology. -

Southampton French Quarter 1382 Specialist Report Download E9: Mineralised and Waterlogged Fly Pupae, and Other Insects and Arthropods

Southampton French Quarter SOU1382 Specialist Report Download E9 Southampton French Quarter 1382 Specialist Report Download E9: Mineralised and waterlogged fly pupae, and other insects and arthropods By David Smith Methods In addition to samples processed specifically for the analysis of insect remains, insect and arthropod remains, particularly mineralised pupae and puparia, were also contained in the material sampled and processed for plant macrofossil analysis. These were sorted out from archaeobotanical flots and heavy residues fractions by Dr. Wendy Smith (Oxford Archaeology) and relevant insect remains were examined under a low-power binocular microscope by Dr. David Smith. The system for ‘intensive scanning’ of faunas as outlined by Kenward et al. (1985) was followed. The Coleoptera (beetles) present were identified by direct comparison to the Gorham and Girling Collections of British Coleoptera. The dipterous (fly) puparia were identified using the drawings in K.G.V. Smith (1973, 1989) and, where possible, by direct comparison to specimens identified by Peter Skidmore. Results The insect and arthropod taxa recovered are listed in Table 1. The taxonomy used for the Coleoptera (beetles) follows that of Lucht (1987). The numbers of individual insects present is estimated using the following scale: + = 1-2 individuals ++ = 2-5 individuals +++ = 5-10 individuals ++++ = 10-20 individuals +++++ = 20- 100individuals +++++++ = more than 100 individuals Discussion The insect and arthropod faunas from these samples were often preserved by mineralisation with any organic material being replaced. This did make the identification of some of the fly pupae, where some external features were missing, problematic. The exceptions to this were samples 108 (from a Post Medieval pit), 143 (from a High Medieval pit) and 146 (from an Anglo-Norman well) where the material was partially preserved by waterlogging. -

The Beetle Fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and Distribution

INSECTA MUNDI, Vol. 20, No. 3-4, September-December, 2006 165 The beetle fauna of Dominica, Lesser Antilles (Insecta: Coleoptera): Diversity and distribution Stewart B. Peck Department of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6, Canada stewart_peck@carleton. ca Abstract. The beetle fauna of the island of Dominica is summarized. It is presently known to contain 269 genera, and 361 species (in 42 families), of which 347 are named at a species level. Of these, 62 species are endemic to the island. The other naturally occurring species number 262, and another 23 species are of such wide distribution that they have probably been accidentally introduced and distributed, at least in part, by human activities. Undoubtedly, the actual numbers of species on Dominica are many times higher than now reported. This highlights the poor level of knowledge of the beetles of Dominica and the Lesser Antilles in general. Of the species known to occur elsewhere, the largest numbers are shared with neighboring Guadeloupe (201), and then with South America (126), Puerto Rico (113), Cuba (107), and Mexico-Central America (108). The Antillean island chain probably represents the main avenue of natural overwater dispersal via intermediate stepping-stone islands. The distributional patterns of the species shared with Dominica and elsewhere in the Caribbean suggest stages in a dynamic taxon cycle of species origin, range expansion, distribution contraction, and re-speciation. Introduction windward (eastern) side (with an average of 250 mm of rain annually). Rainfall is heavy and varies season- The islands of the West Indies are increasingly ally, with the dry season from mid-January to mid- recognized as a hotspot for species biodiversity June and the rainy season from mid-June to mid- (Myers et al. -

Coleoptera Identifying the Beetles

6/17/2020 Coleoptera Identifying the Beetles Who we are: Matt Hamblin [email protected] Graduate of Kansas State University in Manhattan, KS. Bachelors of Science in Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Biology Minor in Entomology Began M.S. in Entomology Fall 2018 focusing on Entomology Education Who we are: Jacqueline Maille [email protected] Graduate of Kansas State University in Manhattan, KS with M.S. in Entomology. Austin Peay State University in Clarksville, TN with a Bachelors of Science in Biology, Minor Chemistry Began Ph.D. iin Entomology with KSU and USDA-SPIERU in Spring 2020 Focusing on Stored Product Pest Sensory Systems and Management 1 6/17/2020 Who we are: Isaac Fox [email protected] 2016 Kansas 4-H Entomology Award Winner Pest Scout at Arnold’s Greenhouse Distribution, Abundance and Diversity Global distribution Beetles account for ~25% of all life forms ~390,000 species worldwide What distinguishes a beetle? 1. Hard forewings called elytra 2. Mandibles move horizontally 3. Antennae with usually 11 or less segments exceptions (Cerambycidae Rhipiceridae) 4. Holometabolous 2 6/17/2020 Anatomy Taxonomically Important Features Amount of tarsi Tarsal spurs/ spines Antennae placement and features Elytra features Eyes Body Form Antennae Forms Filiform = thread-like Moniliform = beaded Serrate = sawtoothed Setaceous = bristle-like Lamellate = nested plates Pectinate = comb-like Plumose = long hairs Clavate = gradually clubbed Capitate = abruptly clubbed Aristate = pouch-like with one lateral bristle Nicrophilus americanus Silphidae, American Burying Beetle Counties with protected critical habitats: Montgomery, Elk, Chautauqua, and Wilson Red-tipped antennae, red pronotum The ecological services section, Kansas department of Wildlife, Parks, and Tourism 3 6/17/2020 Suborders Adephaga vs Polyphaga Families ~176 described families in the U.S. -

Superfamilies Tephritoidea and Sciomyzoidea (Dip- Tera: Brachycera) Kaj Winqvist & Jere Kahanpää

20 © Sahlbergia Vol. 12: 20–32, 2007 Checklist of Finnish flies: superfamilies Tephritoidea and Sciomyzoidea (Dip- tera: Brachycera) Kaj Winqvist & Jere Kahanpää Winqvist, K. & Kahanpää, J. 2007: Checklist of Finnish flies: superfamilies Tephritoidea and Sciomyzoidea (Diptera: Brachycera). — Sahlbergia 12:20-32, Helsinki, Finland, ISSN 1237-3273. Another part of the updated checklist of Finnish flies is presented. This part covers the families Lonchaeidae, Pallopteridae, Piophilidae, Platystomatidae, Tephritidae, Ulididae, Coelopidae, Dryomyzidae, Heterocheilidae, Phaeomyii- dae, Sciomyzidae and Sepsidae. Eight species are recorded from Finland for the first time. The following ten species have been erroneously reported from Finland and are here deleted from the Finnish checklist: Chaetolonchaea das- yops (Meigen, 1826), Earomyia crystallophila (Becker, 1895), Lonchaea hirti- ceps Zetterstedt, 1837, Lonchaea laticornis Meigen, 1826, Prochyliza lundbecki (Duda, 1924), Campiglossa achyrophori (Loew, 1869), Campiglossa irrorata (Fallén, 1814), Campiglossa tessellata (Loew, 1844), Dioxyna sororcula (Wie- demann, 1830) and Tephritis nigricauda (Loew, 1856). The Finnish records of Lonchaeidae: Lonchaea bruggeri Morge, Lonchaea contigua Collin, Lonchaea difficilis Hackman and Piophilidae: Allopiophila dudai (Frey) are considered dubious. The total number of species of Tephritoidea and Sciomyzoidea found from Finland is now 262. Kaj Winqvist, Zoological Museum, University of Turku, FI-20014 Turku, Finland. Email: [email protected] Jere Kahanpää, Finnish Environment Institute, P.O. Box 140, FI-00251 Helsinki, Finland. Email: kahanpaa@iki.fi Introduction new millennium there was no concentrated The last complete checklist of Finnish Dipte- Finnish effort to study just these particular ra was published in Hackman (1980a, 1980b). groups. Consequently, before our work the Recent checklists of Finnish species have level of knowledge on Finnish fauna in these been published for ‘lower Brachycera’ i.e. -

0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 Concatenated Blaesoxipha Alcedo Blaesoxipha

Blaesoxipha alcedo Blaesoxipha masculina 1.0001.000Calliphora maestrica DR084 Calliphora maestrica DR088 Lucilia cluvia FL017 1.0001.0000.5150.515Lucilia cluvia FL020 0.9970.997Lucilia cluvia FL025 0.6090.609Lucilia cluvia FL026 0.9880.988Lucilia cluvia PR147 Lucilia cluvia PR148 Lucilia coeruleiviridis FL013 0.7080.7080.1350.135Lucilia coeruleiviridis FL015 0.1100.110Lucilia coeruleiviridis FL023 0.8390.8390.1330.133Lucilia coeruleiviridis FL016 Lucilia coeruleiviridis FL024 0.3350.335 0.4650.465 0.3350.335Lucilia mexicana ME016 0.4650.465 1.0001.000Lucilia mexicana ME021 Lucilia mexicana ME020 0.9880.988 1.0001.0001.0001.000Lucilia eximia FL021 Lucilia eximia FL022 Lucilia sp CO027 1.0001.0000.3470.347Lucilia vulgata CO019 1.0001.000 1.0001.000Lucilia vulgata CO028 1.0001.000Lucilia vulgata CO025 Lucilia vulgata CO026 0.9590.959Lucilia eximia CO012 0.6080.608Lucilia eximia CO015 Lucilia eximia CO022 0.9690.969 0.4240.4240.3270.327 0.9690.969 1.0001.0000.3270.327Lucilia eximia CO023 0.9070.907Lucilia eximia ME005 0.9980.998 1.0001.000 Lucilia eximia ME007 Lucilia eximia CO013 1.0001.0000.3880.388Lucilia eximia SLU LA124 Lucilia eximia SLU LA127 0.8700.870Lucilia eximia DOM LA064 Lucilia eximia DOM LA065 0.7710.771 0.7710.771 1.0001.000Lucilia fayeae M079 0.9730.973Lucilia fayeae PR008 1.0001.000 0.9730.973 0.5120.512Lucilia fayeae PR023 0.9850.985Lucilia fayeae PR045 1.0001.000 Lucilia fayeae PR053 0.3310.331Lucilia retroversa CU007 0.9910.991 0.9350.935 1.0001.000Lucilia retroversa DR024 1.0001.000Lucilia retroversa DR123 0.9970.997 -

From an Easy Method to Computerized Species Determination

insects Article Connecting the Dots: From an Easy Method to Computerized Species Determination Senta Niederegger 1,*, Klaus-Peter Döge 2, Marcus Peter 2, Tobias Eickhölter 2 and Gita Mall 1 1 Institute of Legal Medicine, University Hospital Jena, Am Klinikum 1, 07747 Jena, Germany; [email protected] 2 Department of Electrical Engineering and Information Technology, University of Applied Sciences Jena, Carl-Zeiss-Promenade 2, 07745 Jena, Germany; [email protected] (K.-P.D.); [email protected] (M.P.); [email protected] (T.E.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-3641-9397130 Academic Editors: David Rivers and John R. Wallace Received: 8 March 2017; Accepted: 12 May 2017; Published: 18 May 2017 Abstract: Differences in growth rate of forensically important dipteran larvae make species determination an essential requisite for an accurate estimation of time since colonization of the body. Interspecific morphological similarities, however, complicate species determination. Muscle attachment site (MAS) patterns on the inside of the cuticula of fly larvae are species specific and grow proportionally with the animal. The patterns can therefore be used for species identification, as well as age estimation in forensically important dipteran larvae. Additionally, in species where determination has proven to be difficult—even when employing genetic methods—this easy and cheap method can be successfully applied. The method was validated for a number of Calliphoridae, as well as Sarcophagidae; for Piophilidae species, however, the method proved to be inapt. The aim of this article is to assess the utility of the MAS method for applications in forensic entomology. -

VETERİNER HEKİMLER DERNEĞİ DERGİSİ Evaluation Of

Vet Hekim Der Derg 91 (1): 44-48, 2020 ISSN: 0377-6395 VETERİNER HEKİMLER DERNEĞİ DERGİSİ e-ISSN: 2651-4214 JOURNAL OF THE TURKISH VETERINARY MEDICAL SOCIETY Dergi ana sayfası: Journal homepage: http://derGipark.orG.tr/vetheder DOI: 10.33188/vetheder.555442 Araştırma Makalesi / Research Article Evaluation of relation With pet food and first record of Necrobia rufipes (De Geer, 1775) (Coleoptera: Cleridae) associated With pet clinic in Turkey Nafiye KOÇ 1, a*, Mert ARSLANBAŞ 1, b, Canberk TİFTİKÇİOĞLU 1, c, Ayşe ÇAKMAK 1, d, A. Serpil NALBANTOĞLU 1, e 1 Ankara University Faculty of Veterinary Medicine Department of Parasitology, 06110 TURKEY ORCID: 0000-0003-2944-9402 a, 0000-0002-9307-4441 b, 0000-0003-1828-1122 c, 0000-0003-2606-2413 d, 0000-0002-9670-7566 e MAKALE BILGISI: ABSTRACT: ARTICLE The purpose of this study is to report clinical infestations caused by Necrobia rufipes (N. rufipes), mainly related to INFORMATION: forensic entomology, in pet food. As a result of the evaluation of the infested materials which came to our laboratory within the scope of the study, clinical observations were made to understand the intensity of infestations in the region and Geliş / Received: to learn their origins. As a result, dry cat and dog foods were determined to be responsible for infestation. During the 18 Nisan 2019 observations, intense insect populations were found, especially in pet food bowl and bags. The related insects have caused considerable loss of product and significant economic damage in infested pouches. Reports on clinical infestations 18 April 2019 from N. rufipes are quite rare. -

Enhancing Forensic Entomology Applications: Identification and Ecology

Enhancing forensic entomology applications: identification and ecology A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in the Faculty of Arts and Science TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada © Copyright by Sarah Victoria Louise Langer 2017 Environmental and Life Sciences M.Sc. Graduate Program September 2017 ABSTRACT Enhancing forensic entomology applications: identification and ecology Sarah Victoria Louise Langer The purpose of this thesis is to enhance forensic entomology applications through identifications and ecological research with samples collected in collaboration with the OPP and RCMP across Canada. For this, we focus on blow flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) and present data collected from 2011-2013 from different terrestrial habitats to analyze morphology and species composition. Specifically, these data were used to: 1) enhance and simplify morphological identifications of two commonly caught forensically relevant species; Phormia regina and Protophormia terraenovae, using their frons-width to head- width ratio as an additional identifying feature where we found distinct measurements between species, and 2) to assess habitat specificity for urban and rural landscapes, and the scale of influence on species composition when comparing urban and rural habitats across all locations surveyed where we found an effect of urban habitat on blow fly species composition. These data help refine current forensic entomology applications by adding to the growing knowledge of distinguishing morphological features, and our understanding of habitat use by Canada’s blow fly species which may be used by other researchers or forensic practitioners. Keywords: Calliphoridae, Canada, Forensic Science, Morphology, Cytochrome Oxidase I, Distribution, Urban, Ecology, Entomology, Forensic Entomology ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “Blow flies are among the most familiar of insects. -

Terry Whitworth 3707 96Th ST E, Tacoma, WA 98446

Terry Whitworth 3707 96th ST E, Tacoma, WA 98446 Washington State University E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Published in Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington Vol. 108 (3), 2006, pp 689–725 Websites blowflies.net and birdblowfly.com KEYS TO THE GENERA AND SPECIES OF BLOW FLIES (DIPTERA: CALLIPHORIDAE) OF AMERICA, NORTH OF MEXICO UPDATES AND EDITS AS OF SPRING 2017 Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 Materials and Methods ................................................................................................... 5 Separating families ....................................................................................................... 10 Key to subfamilies and genera of Calliphoridae ........................................................... 13 See Table 1 for page number for each species Table 1. Species in order they are discussed and comparison of names used in the current paper with names used by Hall (1948). Whitworth (2006) Hall (1948) Page Number Calliphorinae (18 species) .......................................................................................... 16 Bellardia bayeri Onesia townsendi ................................................... 18 Bellardia vulgaris Onesia bisetosa .....................................................