A Sociolinguistic Survey of the Mambay Language Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linguapax Review 2010 Linguapax Review 2010

LINGUAPAX REVIEW 2010 MATERIALS / 6 / MATERIALS Col·lecció Materials, 6 Linguapax Review 2010 Linguapax Review 2010 Col·lecció Materials, 6 Primera edició: febrer de 2011 Editat per: Amb el suport de : Coordinació editorial: Josep Cru i Lachman Khubchandani Traduccions a l’anglès: Kari Friedenson i Victoria Pounce Revisió dels textos originals en anglès: Kari Friedenson Revisió dels textos originals en francès: Alain Hidoine Disseny i maquetació: Monflorit Eddicions i Assessoraments, sl. ISBN: 978-84-15057-12-3 Els continguts d’aquesta publicació estan subjectes a una llicència de Reconeixe- ment-No comercial-Compartir 2.5 de Creative Commons. Se’n permet còpia, dis- tribució i comunicació pública sense ús comercial, sempre que se’n citi l’autoria i la distribució de les possibles obres derivades es faci amb una llicència igual a la que regula l’obra original. La llicència completa es pot consultar a: «http://creativecom- mons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/es/deed.ca» LINGUAPAX REVIEW 2010 Centre UNESCO de Catalunya Barcelona, 2011 4 CONTENTS PRESENTATION Miquel Àngel Essomba 6 FOREWORD Josep Cru 8 1. THE HISTORY OF LINGUAPAX 1.1 Materials for a history of Linguapax 11 Fèlix Martí 1.2 The beginnings of Linguapax 14 Miquel Siguan 1.3 Les débuts du projet Linguapax et sa mise en place 17 au siège de l’UNESCO Joseph Poth 1.4 FIPLV and Linguapax: A Quasi-autobiographical 23 Account Denis Cunningham 1.5 Defending linguistic and cultural diversity 36 1.5 La defensa de la diversitat lingüística i cultural Fèlix Martí 2. GLIMPSES INTO THE WORLD’S LANGUAGES TODAY 2.1 Living together in a multilingual world. -

November 2011 EPIGRAPH

République du Cameroun Republic of Cameroon Paix-travail-patrie Peace-Work-Fatherland Ministère de l’Emploi et de la Ministry of Employment and Formation Professionnelle Vocational Training INSTITUT DE TRADUCTION INSTITUTE OF TRANSLATION ET D’INTERPRETATION AND INTERPRETATION (ISTI) AN APPRAISAL OF THE ENGLISH VERSION OF « FEMMES D’IMPACT : LES 50 DES CINQUANTENAIRES » : A LEXICO-SEMANTIC ANALYSIS A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of a Vocational Certificate in Translation Studies Submitted by AYAMBA AGBOR CLEMENTINE B. A. (Hons) English and French University of Buea SUPERVISOR: Dr UBANAKO VALENTINE Lecturer University of Yaounde I November 2011 EPIGRAPH « Les écrivains produisent une littérature nationale mais les traducteurs rendent la littérature universelle. » (Jose Saramago) i DEDICATION To all my loved ones ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Immense thanks goes to my supervisor, Dr Ubanako, who took out time from his very busy schedule to read through this work, propose salient guiding points and also left his personal library open to me. I am also indebted to my lecturers and classmates at ISTI who have been warm and friendly during this two-year programme, which is one of the reasons I felt at home at the institution. I am grateful to IRONDEL for granting me the interview during which I obtained all necessary information concerning their document and for letting me have the book at a very moderate price. Some mistakes in this work may not have been corrected without the help of Mr. Ngeh Deris whose proofreading aided the researcher in rectifying some errors. I also thank my parents, Mr. -

Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit?

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1| Jan-Feb-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.003 Research Article Options for a National Culture Symbol of Cameroon: Can the Bamenda Grassfields Traditional Dress Fit? Venantius Kum NGWOH Ph.D* Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Buea, Cameroon Abstract: The national symbols of Cameroon like flag, anthem, coat of arms and seal do not Article History in any way reveal her cultural background because of the political inclination of these signs. Received: 14.01.2020 In global sporting events and gatherings like World Cup and international conferences Accepted: 28.12.2020 respectively, participants who appear in traditional costume usually easily reveal their Published: 17.02.2020 nationalities. The Ghanaian Kente, Kenyan Kitenge, Nigerian Yoruba outfit, Moroccan Journal homepage: Djellaba or Indian Dhoti serve as national cultural insignia of their respective countries. The https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs reason why Cameroon is referred in tourist circles as a cultural mosaic is that she harbours numerous strands of culture including indigenous, Gaullist or Francophone and Anglo- Quick Response Code Saxon or Anglophone. Although aspects of indigenous culture, which have been grouped into four spheres, namely Fang-Beti, Grassfields, Sawa and Sudano-Sahelian, are dotted all over the country in multiple ways, Cameroon cannot still boast of a national culture emblem. The purpose of this article is to define the major components of a Cameroonian national culture and further identify which of them can be used as an acceptable domestic cultural device. -

PCD LAGDO.Pdf

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix – Travail – Patrie Peace-Work-Fatherland ********* *********** MINISTERE DE L’ADMINISTRATION MINISTRY OF TERRITORIAL TERRITORIALE ET DE LA ADMINISTRATION DECENTRALISATION AND DECENTRALISATION *********** *********** REGION DU NORD NORTH REGION *********** *********** DEPARTEMENT DE LA BENOUE BENUE DIVISION *********** *********** COMMUNE DE LAGDO LADGO COUNCIL *********** *********** PLAN COMMUNAL DE DEVELOPPEMENT D E L A G D O PLANIFICATION COMMUNALE AVEC L’APPUI DU PNDP juin 2015 Programme National de Développement Participatif (PNDP)-Cellule Régionale de Coordination du Nord -Tél : 22 27 10 70 / 98 49 89 91 – E Mail : [email protected]– Site Web : www.pndp.org g i SOMMAIRE SOMMAIRE ......................................................................................................................................................... ii RESUME DU PCD ................................................................................................................................................ vi LISTE DES ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................... vii LISTE DES TABLEAUX ......................................................................................................................................... xii LISTE DES PHOTOS ........................................................................................................................................... xiii LISTE DES CARTES -

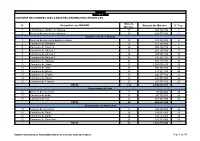

De 40 MINMAP Région Du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES

MINMAP Région du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° Page Marchés 1 Communauté Urbaine de Garoua 11 847 894 350 3 2 Services déconcentrés régionaux 20 528 977 000 4 Département de la Bénoué 3 Services déconcentrés départementaux 10 283 500 000 6 4 Commune de Barndaké 13 376 238 000 7 5 Commune de Bascheo 16 305 482 770 8 6 Commune de Garoua 1 11 201 187 000 9 7 Commune de Garoua 2 26 498 592 344 10 8 Commune de Garoua 3 22 735 201 727 12 9 Commune de Gashiga 21 353 419 404 14 10 Commune de Lagdo 21 2 026 560 930 16 11 Commune de Pitoa 18 360 777 700 18 12 Commune de Bibémi 18 371 277 700 20 13 Commune de Dembo 11 300 277 700 21 14 Commune de Ngong 12 235 778 000 22 15 Commune de Touroua 15 187 777 700 23 TOTAL 214 6 236 070 975 Département du Faro 16 Services déconcentrés 5 96 500 000 25 17 Commune de Beka 15 230 778 000 25 18 Commune de Poli 22 481 554 000 26 TOTAL 42 808 832 000 Département du Mayo-Louti 19 Services déconcentrés 6 196 000 000 28 20 Commune de Figuil 16 328 512 000 28 21 Commune de Guider 28 534 529 000 30 22 Commune de Mayo Oulo 24 331 278 000 32 TOTAL 74 1 390 319 000 MINMAP / DIVISION DE LA PROGRAMMATION ET DU SUIVI DES MARCHES PUBLICS Page 1 de 40 MINMAP Région du Nord SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de N° Désignation des MO/MOD Montant des Marchés N° Page Marchés Département du Mayo-Rey 23 Services déconcentrés 7 152 900 000 35 24 Commune de Madingring 14 163 778 000 35 24 Commune de Rey Bouba -

Cameroon : Adamawa, East and North Rgeions

CAMEROON : ADAMAWA, EAST AND NORTH RGEIONS 11° E 12° E 13° E 14° E N 1125° E 16° E Hossere Gaval Mayo Kewe Palpal Dew atan Hossere Mayo Kelvoun Hossere HDossere OuIro M aArday MARE Go mbe Trabahohoy Mayo Bokwa Melendem Vinjegel Kelvoun Pandoual Ourlang Mayo Palia Dam assay Birdif Hossere Hosere Hossere Madama CHARI-BAGUIRMI Mbirdif Zaga Taldam Mubi Hosere Ndoudjem Hossere Mordoy Madama Matalao Hosere Gordom BORNO Matalao Goboum Mou Mayo Mou Baday Korehel Hossere Tongom Ndujem Hossere Seleguere Paha Goboum Hossere Mokoy Diam Ibbi Moukoy Melem lem Doubouvoum Mayo Alouki Mayo Palia Loum as Marma MAYO KANI Mayo Nelma Mayo Zevene Njefi Nelma Dja-Lingo Birdi Harma Mayo Djifi Hosere Galao Hossere Birdi Beli Bili Mandama Galao Bokong Babarkin Deba Madama DabaGalaou Hossere Goudak Hosere Geling Dirtehe Biri Massabey Geling Hosere Hossere Banam Mokorvong Gueleng Goudak Far-North Makirve Dirtcha Hwoli Ts adaksok Gueling Boko Bourwoy Tawan Tawan N 1 Talak Matafal Kouodja Mouga Goudjougoudjou MasabayMassabay Boko Irguilang Bedeve Gimoulounga Bili Douroum Irngileng Mayo Kapta Hakirvia Mougoulounga Hosere Talak Komboum Sobre Bourhoy Mayo Malwey Matafat Hossere Hwoli Hossere Woli Barkao Gande Watchama Guimoulounga Vinde Yola Bourwoy Mokorvong Kapta Hosere Mouga Mouena Mayo Oulo Hossere Bangay Dirbass Dirbas Kousm adouma Malwei Boulou Gandarma Boutouza Mouna Goungourga Mayo Douroum Ouro Saday Djouvoure MAYO DANAY Dum o Bougouma Bangai Houloum Mayo Gottokoun Galbanki Houmbal Moda Goude Tarnbaga Madara Mayo Bozki Bokzi Bangei Holoum Pri TiraHosere Tira -

Multilingual Cameroon

GOTHENBURG AFRICANA INFORMAL SERIES – NO 7 ______________________________________________________ Multilingual Cameroon Policy, Practice, Problems and Solutions by Tove Rosendal DEPARTMENT OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN LANGUAGES 2008 2 Contents List of tables ..................................................................................................................... 4 List of figures ................................................................................................................... 4 Abbreviations ................................................................................................................... 5 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 9 2. Focus, methodology and earlier studies ................................................................. 11 3. Language policy in Cameroon – historical overview............................................. 13 3.1 Pre-independence period ................................................................................ 13 3.2 Post-independence period............................................................................... 13 4. The languages of Cameroon................................................................................... 14 4.1 The national languages of Cameroon - an overview ...................................... 14 4.1.1 The language families of Cameroon....................................................... 16 4.1.2 Languages of wider distribution............................................................ -

Central Africa, 2021 Region of Africa

Quickworld Entity Report Central Africa, 2021 Region of Africa Quickworld Factoid Name : Central Africa Status : Region of Africa Land Area : 7,215,000 sq km - 2,786,000 sq mi Political Entities Sovereign Countries (19) Angola Burundi Cameroon Central African Republic Chad Congo (DR) Congo (Republic) Equatorial Guinea Gabon Libya Malawi Niger Nigeria Rwanda South Sudan Sudan Tanzania Uganda Zambia International Organizations Worldwide Organizations (3) Commonwealth of Nations La Francophonie United Nations Organization Continental Organizations (1) African Union Conflicts and Disputes Internal Conflicts and Secessions (1) Lybian Civil War Territorial Disputes (1) Sudan-South Sudan Border Disputes Languages Language Families (9) Bihari languages Central Sudanic languages Chadic languages English-based creoles and pidgins French-based creoles and pidgins Manobo languages Portuguese-based creoles and pidgins Prakrit languages Songhai languages © 2019 Quickworld Inc. Page 1 of 7 Quickworld Inc assumes no responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions in the content of this document. The information contained in this document is provided on an "as is" basis with no guarantees of completeness, accuracy, usefulness or timeliness. Quickworld Entity Report Central Africa, 2021 Region of Africa Languages (485) Abar Acoli Adhola Aghem Ajumbu Aka Aka Akoose Akum Akwa Alur Amba language Ambele Amdang Áncá Assangori Atong language Awing Baali Babango Babanki Bada Bafaw-Balong Bafia Bakaka Bakoko Bakole Bala Balo Baloi Bambili-Bambui Bamukumbit -

James N. Stanford, Ph.D. Professor and Chair Department of Linguistics Dartmouth College

James N. Stanford, Ph.D. Professor and Chair Department of Linguistics Dartmouth College Office and Postal Address: Contact: Department of Linguistics [email protected] HB 6220 - Anon. Hall room 218 (603)646-0099 Dartmouth College Hanover, NH 03755 ACADEMIC POSITIONS July 2019 to present: Chair of Dartmouth Department of Linguistics July 2020 to present: Professor of Linguistics, Dartmouth Editorial positions: Editorial Board, Language Variation and Change, 2015-present Associate Editor, Asia-Pacific Language Variation, 2015-present Associate Editor, Frontiers: Computational Sociolinguistics, 2018-present Editorial Advisory Committee, American Speech, 2018-2020 July 2014 to June 2020: Associate Professor of Linguistics, Dartmouth Winter 2013: Acting Chair of the Dartmouth Linguistics and Cognitive Science Program July 2008 to June 2014: Assistant Professor of Linguistics and Cognitive Science, Dartmouth Fall 2007-Spring 2008: Lecturer, Rice University Linguistics Department AWARDS AND FUNDING Dartmouth Dean of the Faculty Award for Outstanding Mentoring and Advising (2020) Karen E. Wetterhahn Award for Distinguished Creative or Scholarly Achievement (2014) PI, Scholarly Innovation and Advancement Award, Dartmouth College, $40,000 (2018-2020) Sociolinguistic exploration of a matrilineal/matrilocal society in rural southwest China PI, National Science Foundation grant with Kalina Newmark '11 and Nacole Walker '11 English dialect features of indigenous people in North America: A cross-continental investigation (2013-16), $87,679 -

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report

Cameroon Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Cameroon/2019 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights August 2019 2,300,000 • More than 118,000 people have benefited from UNICEF’s # of children in need of humanitarian assistance humanitarian assistance in the North-West and South-West 4,300,000 regions since January including 15,800 in August. # of people in need (Cameroon Humanitarian Needs Overview 2019) • The Rapid Response Mechanism (RRM) strategy, Displacement established in the South-West region in June, was extended 530,000 into the North-West region in which 1,640 people received # of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in the North- WASH kits and Long-Lasting Insecticidal Nets (LLINs) in West and South-West regions (OCHA Displacement Monitoring, July 2019) August. 372,854 # of IDPs and Returnees in the Far-North region • In August, 265,694 children in the Far-North region were (IOM Displacement Tracking Matrix 18, April 2019) vaccinated against poliomyelitis during the final round of 105,923 the vaccination campaign launched following the polio # of Nigerian Refugees in rural areas (UNHCR Fact Sheet, July 2019) outbreak in May. UNICEF Appeal 2019 • During the month of August, 3,087 children received US$ 39.3 million psychosocial support in the Far-North region. UNICEF’s Response with Partners Total funding Funds requirement received Sector Total UNICEF Total available 20% $ 4.5M Target Results* Target Results* Carry-over WASH: People provided with 374,758 33,152 75,000 20,181 $ 3.2 M access to appropriate sanitation 2019 funding Education: Number of boys and requirement: girls (3 to 17 years) affected by 363,300 2,415 217,980 0 $39.3 M crisis receiving learning materials Nutrition**: Number of children Funding gap aged 6-59 months with SAM 60,255 39,727 65,064 40,626 $ 31.6M admitted for treatment Child Protection: Children reached with psychosocial support 563,265 160,423 289,789 87,110 through child friendly/safe spaces C4D: Persons reached with key life- saving & behaviour change 385,000 431,034 messages *Total results are cumulative. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

The Evolution of Linguistic Diversity

The Evolution of Linguistic Diversity Daniel Nettle Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD University College London 1996 ProQuest Number: 10044366 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10044366 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the causes and consequences of diversity in human language. It is divided into three sections, each of which addresses a different aspect of the topic. The first section uses computer simulations to examine various mechanisms which may produce diversity in language: imperfect learning, geographical isolation, selection on the basis of social affiliation, and functional selection amongst linguistic variants. It is concluded that social and functional selection by speakers provide the main motive forces for the divergence of languages. The second section examines the factors influencing the geographical distribution of languages in the world. By far the most important is the ecological regime in which people live. Seasonal climates produce large ethnolinguistic groups because people form large networks of exchange to mitigate the subsistence risk to which they are exposed.