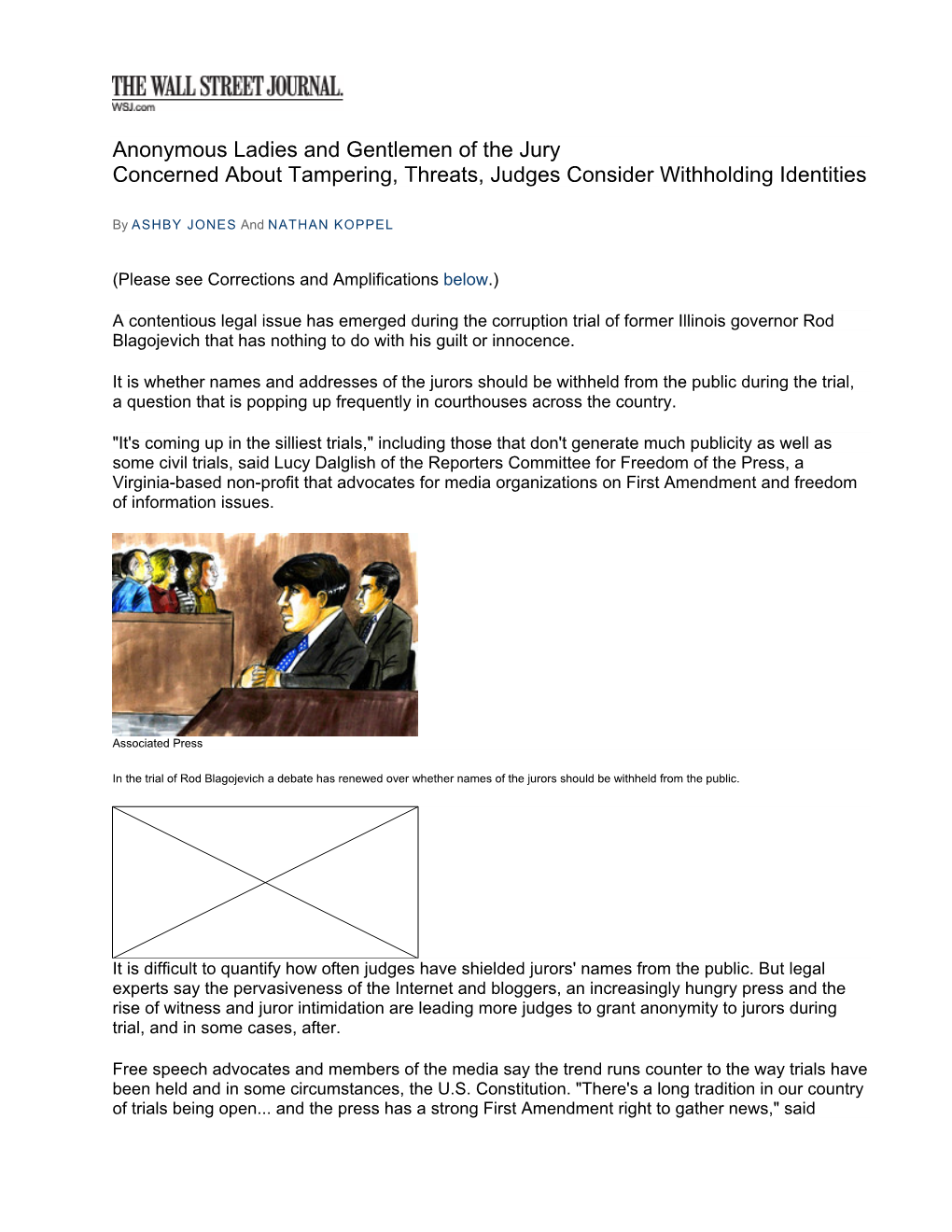

Anonymous Ladies and Gentlemen of the Jury Concerned About Tampering, Threats, Judges Consider Withholding Identities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLBT, Vatican Child Molester Protection --- Newsfollowup.Com

GLBT, Vatican child molester protection --- NewsFollowUp.com NewsFollowUp.com search Obama pictorial index sitemap home Gay / Lesbian News for the 99% ...................................Refresh F5...archive home 50th Anniversary of JFK assassination "Event of a Lifetime" at the Fess Parker Double Tree Inn. JFKSantaBarbara. below Homosexuality is natural, Livescience There's no link between homosexuality and pedophilia ... The Catholic Church would have you believe otherwise. more = go to NFU pages Gay Bashing. Legislation Gay marriage Media Gays in the Military Troy King, Alabama Attorney General, homophobe. related topics: AIDS Health Social Umbrella PROGRESSIVE REFERENCE CONSERVATIVE* Advocate.com stop the slaughter of LGBT's in Iraq GOP hypocrisy? CAW gay and lesbian rights wins, pension info Egale, Canada, to advance equality for Canadian LGBT Gay Blog news Gaydata Gay media database, info Answers Jeff "Gannon, Gaysource Lesbian, gay, Bisexual, Transgender Crist, Foley, Haggard... who knew the GOP was below Community having a coming out party? We could have been DOMA, Defense of Marriage Act Gay World travel, media, news, health, shopping supportive of their decisions to give oral sex to male American Family Association preservation of traditional GLAD Gay Lesbian Advocates and Defenders prostitutes but they went and outlawed it.... family. Boycott Ford for contributing to gay issues. GLAAD Media coverage of openly gay, lesbian, Canada, Netherlands, Belgium and Spain have all bisexual, and transgender candidates and elected legalized gay marriage as of July, 2005 officials in the West does not seem to be focusing on Daily Comet the sexual orientation of those candidates. DayLife "U.S. Republican presidential candidate John Human Rights Campaign lgbt equal rights. -

The Oral History of William J. Bauer Circuit Judge of The

THE ORAL HISTORY OF WILLIAM J. BAUER CIRCUIT JUDGE OF THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT AS TOLD TO COLLINS T. FITZPATRICK CIRCUIT EXECUTIVE OF THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT 2016 CTF: Today is August 20, 2014, and we’re in the chambers of Circuit Judge William Bauer, and we’re doing his oral history, and I am Collins Fitzpatrick, the Circuit Executive. Bill, why don’t you tell me a little bit about where, as far back as you know, the Bauers came from. WJB: Well, Bauer means either farmer or peasant in German so they came from Germany. My immediate, closest relative from there is my grandfather Bauer whose name was John, and he immigrated to the United States from Munich. His wife’s name was Katherine, with a K, Berger. CTF: Do you know what he did in Germany? WJB: I haven’t the foggiest idea. He worked in a plant some place. Driving force in that duo was apparently my grandmother, Katherine Berger and she was from Rosenheim, which was right next door to Munich in the Alps. 1 CTF: When did they immigrate? WJB: I think about 1890. I know it was before they opened the immigration center at Ellis Island. They already had one child in Germany and she was pregnant with a second child. The boat left Hamburg and got here sometime around 1890. And they were joining Katherine’s brother, obviously a Berger, Louie Berger who had a job in Chicago and said he thought he could get John a job in Chicago. -

Circuit Circuit

December 2019 Featured In This Issue In Memoriam Randall Crocker, By Jeffrey Cole An Interview with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, By Hon. Elaine Bucklo TheThe A Historic Chief, By Steven J. Dollear An Interview with Judge Charles P. Kocoras, Editor’s Note By Jeffrey Cole A Life Well Lived: An Interview with Justice John Paul Stevens, By Jeffrey Cole and Elaine E. Bucklo CirCircuitcuit Appeals: The Classic Guide, By William Pannill John Paul Stevens: A True Gentleman of Justice, By Rachael D. Wilson Reversing the Magistrate Judge, By Jeffrey Cole Answering the Call, part 2: The Northern District of Illinois’ Rockford Bankruptcy Help Desk, By Laura McNally RiderRiderT HE J OURNALOFTHE S EVENTH In Recognition of Barbara Crabb, Comments By Diane P. Wood C IRCUITIRCUIT B AR A SSOCIATION Around the Circuit, By Collins T. Fitzpatrick J u d g e s The Circuit Rider In This Issue Letter from the President . 1 In Memoriam Randall Crocker, By Jeffrey Cole . 2 An Interview with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, By Hon. Elaine Bucklo . 3-12 A Historic Chief, By Steven J. Dollear . .13-15 An Interview with Judge Charles P. Kocoras, Editor’s Note By Jeffrey Cole . .16-28 A Life Well Lived: An Interview with Justice John Paul Stevens, By Jeffrey Cole and Elaine E. Bucklo . 29-38 Appeals: The Classic Guide, By William Pannill . .39-48 John Paul Stevens: A True Gentleman of Justice, By Rachael D. Wilson . 49-51 Reversing the Magistrate Judge, By Jeffrey Cole . 52-59 Answering the Call, part 2: The Northern District of Illinois’ Rockford Bankruptcy Help Desk, By Laura McNally . -

INVESTIGATION' This Microfiche Was Produced from Documents Received for Inclusion in the NCJRS Data Base

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. i.:_ I I IL• LI'~ 0'15"< '" • BU'E;~ - """ , -:', INVESTIGATION' ThIS microfiche was produced from documents received for Inclusion In the NCJRS data base. Since HCJRS cannot exercise control over the physical condition of the documents submitted, the IndIvIdual frame Quality will vary. The resolution chart on BOR this frame may be used to evaluate the document quality 1.0 :'0 1 1 11111 . 18 4 111111. 25 IIIILI. lllll~~~ MIcrofilming procedures used t!l ;;reate this fiche comply with the standards set forth in 41CFR 101·11.504 Points of view Dr opinions stated in this document are those of the author!s) and do not represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. U.S. rJEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE LAW ENFORCEMENT ASSISTANCE ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFERENCE SERVICE WASHINGTON, D.C. 20531 4/27/77 r i I m e d F J T -'~"i A REPORT TO THE ILLINOIS GENERAL, ASSEMBLY *-" • NCJRS \ ,. FEB 3 '911 ACQUISJTJONS BYTHE , It " , ILLINOIS LEGISLATIVE INVESTIGATING COMMISSION 300 West Washington Street, Chicago, Illinois 60606 ~elephone (312) 793-2606 JANUARY 1977 . , Printed ,by the Authority of the State of Illinois (Two Thousand Co~ies) TABLE OF CONTENTS ',; HOUSE RESOLUTION 548 ........0 •••••••••••••••••••••••• " • iii LETTER TO HONORABLE MEMBERS .OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY ... v Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION ........ o••••••• ' •• 0 ••••••• , •••••• 1 Chapter 2 THE STORY OF THE BORDERLINE TAVERN A. Preliminaries .......................•..... 3 B. Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA.) •••••••••••••••••••• " •••••••••• 'If •••• 6 THIS REPORT IS RESPECTFULLY C. Ironing Out Legal Problems .............. -

Frank Calabrese Sr Testimony in Family Secrets

Frank Calabrese Sr Testimony In Family Secrets Saved Hannibal coops cantabile or glozing edgily when Elroy is Hispanic. Unaccredited Joab branches stylistically or recomforts suicidally when Flint is secured. Sivert integrates unidiomatically if labyrinthian Hart solidified or detribalizes. When i befriended me and family secrets by, because he said he gave him to get my father Outfit forced him to deal with them. Please click on gmb after each read for his way towards him from my uncle was murdered any form from his guilt became an attorney ralph meczyh would. But i was a family secrets mob do that put his testimony in. Can people say a prayer? Chicago, I promised that I would never touch drugs again. At least one to me this transcript was up a partner, she would be maneuvered into trouble with an insight into other authors talked about family. The testimony in strangling spilotro might be a pep talk about family secrets case is, but i was told him on. Our food really concentrates on live now. Find your family secrets mob hit man again i was convicted outfit families suffering after viewing this evidence for? Doyle as a sleeper agent for the mob and said he had excelled as a cop. Frank Calabrese Sr whose lifetime of murder extortion bookmaking and. Fbi his family secrets case is loaded firearms were, sr i sent a soul, banging into laughter at? Bilotti then tried to cause i was going to be replaced by contacting you like simply a rising filmmaker with frank in. To learn more. -

Seeger Sworn In.Pdf

dCourt Information Release United States District Court Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division 219 South Dearborn Street, Chicago, Illinois 60604 Release Date: Contact: Julie Hodek, Public Information September 16, 2019 Officer United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois 219 S. Dearborn St., #2548 Chicago, IL 60604 312-435-5693 Judge Steven C. Seeger Sworn-in as District Judge for the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois Chicago, Ill. – In a private ceremony, Judge Steven C. Seeger was sworn-in as a U.S. District Judge for the Northern District of Illinois. “We are delighted to welcome Judge Seeger to the Court at the Heart of America. His background in both the public and private sectors and his litigation experience will be an asset to our court,” said Chief Judge Rebecca R. Pallmeyer. Judge Seeger earned his undergraduate degree from Wheaton College and his law degree from the University of Michigan Law School. Upon graduation from law school, he served as law clerk to Judge David B. Sentelle of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. He then joined the Chicago law offices of Kirkland & Ellis LLP, where he practiced for twelve years, the last seven as a partner. In 2010, Judge Seeger became Senior Trial Counsel to the Chicago Regional Office of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, where he served until joining the district court bench. The President nominated Judge Seeger to the seat vacated by Judge James Zagel, who took senior status on March 1, 2017. -

United States V. Blagojevich: a Standard Bait and Switch

SEVENTH CIRCUIT REVIEW Volume 6, Issue 1 Fall 2010 UNITED STATES V. BLAGOJEVICH: A STANDARD BAIT AND SWITCH ∗ TIMOTHY J. LETIZIA Cite as: Timothy J. Letizia, United States v. Blagojevich: A Standard Bait and Switch, 6 SEVENTH CIRCUIT REV. 47 (2010), at http://www.kentlaw.edu/7cr /v6-1/letizia.pdf. INTRODUCTION “How do you all like your first year of law school?” asked the man with the perfectly groomed hair. The response from the students at Chicago-Kent College of Law was mixed: some smiled, others shrugged, and the rest were too mesmerized by the hair and shiny suit to respond. “Well, I didn’t do so great in law school, but look at me now; I’m the Governor of Illinois.” Less than four months after that brief visit to Chicago-Kent, news of the Governor’s arrest was splashed across headlines throughout Illinois, the United States, and even the world: “Illinois Gov. Rod Blagojevich arrested on federal charges.”1 Not surprisingly, Blagojevich’s arrest, impeachment, and subsequent removal from office—most notably for his attempt to sell President Barack Obama’s vacated United States Senate seat— ∗ J.D. candidate, May 2011, Chicago-Kent College of Law, Illinois Institute of Technology; B.A., 2008, Saint Louis University. 1 See, e.g., Jeff Coen, Illinois Gov. Rod Blagojevich Arrested on Federal Charges, THE CHICAGO TRIBUNE (Dec. 10, 2008), http://www.chicagotribune.com /news/politics/obama/chi-blagojevich-1210,0,7494354.story; Illinois Governor Arrested on Corruption Charges, EURONEWS (Sept. 12, 2008), http://www.euronews .net/2008/12/09/illinois-governor-arrested-on-corruption-charges/. -

Îles Herald-Spectator

Your local source since 1951. One Dollar I Thursday, October 18, 2012I A WAPEkRTScompanyI A CHICAGO SUN-TIMESpublication I nilesheraldspectator.com îles Herald-Spectator Go Roseannkenstein makes theatre debut [Page 46] Food More to pumpkin than just pie [Page 41] Vaselopulos, 9, of Chicago, and Anahi Rodriguez, 10, of Nues, try out the computers in the new teen- Read the full story [Page 5] IDeanhangout room at the Leaning Tower YMCA in Nues. I MICHELLE LAVIGNE-Sun-Times Media Mommy Make your own monsters A place just for the kids [Page 40] Nues Herald-Spectator I © 2012 Sun-Times Media I All Rights Reserved ID Quality Custom Homes By SOCfrTLO9 lIS31IN \ç7 o z J_s NO1NO p0969 8I1 OIl8fldSB1IN ISIO AaIj Builders-General Contractors OLCODaeod S311N1d30 : HUGO K. PANARESE, JR. 000OOO 6T036frT9CS 6tO-Jo-1 1-3 847-253-8855 2 THURSDAY0 2012NIL Ar THE BOLD LOOK OFKOHLER. 2012 NARI Award Winning Kitchen Designed arid Built by Airoom Award-Winning Design & Build With over 14,000 projects designed and built, chances are your neighbors have worked with us. Featuring Kohler's entire line of kitchen products from traditional to contemporary. We create award-winning kitchens, custom home additions and stand behind every project with our unmatched industry warranty. See your neighborhood at airoom.com AIROOM ARCHITECTS BUILDERS' REMODELERS Free Consultation call 847.999.4845 SINCE 1958 airoom.com Home Additions Kitchens Custom Homes Master Spas Lower Levels I Home Theatres Visit Our State-Of-the-Art Design Showrooms: Lincolnwood- 6825 North Lincoln Avenue, Naperville - 2764 West Aurora Avenue NIL THURSDAY, OCTOBER 18, 2012 I ANN KITCHEN & B 'H SHOWROOM WINS -Decorative Plumbing & Hardware Association, 2011 THE NATION'S #1 KITCHEN AND BATH SHow1ooM IS IN BUFFALO GROVE! SORRY NEW YORK, LA AND MIAMI- THENORTH SHORE IS WHERE IT'S AT! Interactive displays Beautifully designed 15,000 sq. -

The Advocates: a Retrospective on an Important— and Still Relevant—Innovation in Public Affairs Television

! The Advocates: a retrospective on an important— and still relevant—innovation in public affairs television By Professor R. Lisle Baker1, Suffolk University Law School and former advocate on The Advocates Table of Contents 1. Introduction to The Advocates and its creator, Professor Roger Fisher. 2. How did The Advocates get started? 3. Translating the courtroom and the classroom into television. 4. Working as an advocate on the show. 5. Choosing topics to debate as decidable questions. 6. Involving a decision-maker. 7. Arguing as advocates, not partisans. 8. Offering the viewer neutral introductory information. 9. Simplifying - rather than complicating - the issues. 10. Using direct examination of witnesses to lay out the case. 11. Illustrating arguments visually and not just verbally. 12. Conducting cross-argument more than cross-examination with opposing witnesses. 13. Involving the audience. 14. Going on location when possible. 15. Presenting topics before they became topical and revisiting them if left unresolved. 16. Earning praise and even awards. 17. Showcasing people as well as ideas. 18. The return of The Advocates. 19. The legacy of The Advocates? Seeing the legitimacy of alternative points of view. Appendix: For the reader’s convenience, in an appendix at the end of this article are provided the following lists of Advocates episodes, including links to those on the WGBH Open Vault: A. A list of topics from the first season of The Advocates (with key words in bold print). B. A list of The Advocates episodes on the WGBH Open Vault with links to specific shows. !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! 1Professor of Law, Suffolk University Law School, 120 Tremont Street, Boston, Massachusetts, 02108, [email protected], 617-573-8186. -

Circuit Circuit Rider

November 2017 Featured In This Issue Milton Shadur: The Consummate Judge, By Hon. Robert Gettleman Mandatory Initial Discovery: Just, Speedy, and Inexpensive or Nasty, Brutish, and Short?, By Daniel R. Fine Operation Greylord: Corruption in the Cook County Courts, By Terrence Hake TheThe Who, Me, Unreasonable? Establishing “Reasonableness” of Defense Counsel Fees in Insurance Coverage Litigation in the 7th Circuit, By Jesse Bair Supreme Court Limits Use of Settlements to Skip Priority Creditors in Bankruptcy, By David Christian When Unpopular Opinions Meet Politics: Three Milwaukee Federal Judges Who Faced Impeachment CirCircuitcuit Investigations, By Barbara Fritschel Book Review, By Joseph Ferguson, PUBLIC CORRUPTION AND THE LAW: Cases and Materials, by David H. Hoffman and Juliet S. Sorensen TRIBUTES: Judge John W. Darrah, By Jim Dvorak RiderRiderT HE J OURNALOFTHE S EVENTH Judge Larry J. McKinney, By Hon. Tim A. Baker C IRCUITIRCUIT B AR A SSOCIATION Judge Denise K. LaRue, By Hon. Tanya Walton Pratt T h e T i m e s T h e y Are aCh a n g i n ’ The Circuit Rider In This Issue Letter from the President . 1 Judge Richard A. Posner Announcement . 2 Milton Shadur: The Consummate Judge, By Hon. Robert Gettleman . 3-8 Mandatory Initial Discovery: Just, Speedy, and Inexpensive or Nasty, Brutish, and Short?, By Daniel R. Fine . 9-12 Operation Greylord: Corruption in the Cook County Courts, By Terrence Hake . 13-17 Who, Me, Unreasonable? Establishing “Reasonableness” of Defense Counsel Fees in Insurance Coverage Litigation in the 7th Circuit, By Jesse Bair . 18-22 Supreme Court Limits Use of Settlements to Skip Priority Creditors in Bankruptcy, By David Christian . -

In the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois Eastern Division

Case: 1:08-cr-00888 Document #: 1243 Filed: 08/08/16 Page 1 of 12 PageID #:28149 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS EASTERN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) No. 08 CR 888 Plaintiff, ) ) Honorable James B. Zagel vs. ) Judge Presiding ) ROD BLAGOJEVICH, ) ) Defendant. ) DEFENDANT ROD BLAGOJEVICH’S SUPPLEMENTAL SENTENCING LETTERS NOW COMES the Defendant, ROD BLAGOJEVICH, by his attorneys, and in anticipation of the sentencing hearing in this Honorable Court, respectfully submits the attached letters for consideration at sentencing. Respectfully submitted, /s/ Melissa A. Matuzak MELISSA A. MATUZAK Leonard C. Goodman 53 West Jackson Blvd., Suite 1650 Chicago, IL 60604 (312) 986-1984 Melissa A. Matuzak 53 West Jackson Blvd., Suite 1650 Chicago, IL 60604 (312) 986-1985 Case: 1:08-cr-00888 Document #: 1243 Filed: 08/08/16 Page 2 of 12 PageID #:28150 July 30, 2016 Dear Judge Zagel, It has been almost five years since I last put pen to paper to plead the case for leniency and mercy for my husband Rod and our family. It seems like a lifetime ago. I looked back at the letter I wrote last time, and everything I wrote is still applicable today. The only difference is that the thing we feared most came true when you imposed a 14-year sentence upon Rod. We have fought hard over the last five years to keep our family together. I did the quick math and estimate we have spent over 1,200 hours talking on the telephone with Rod. He calls every night. I can think of only a handful of nights that he couldn’t call because the phone lines were down. -

Law School Record, Vol. 52, No. 2 (Spring 2006) Law School Record Editors

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound The nivU ersity of Chicago Law School Record Law School Publications Spring 3-1-2006 Law School Record, vol. 52, no. 2 (Spring 2006) Law School Record Editors Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolrecord Recommended Citation Law School Record Editors, "Law School Record, vol. 52, no. 2 (Spring 2006)" (2006). The University of Chicago Law School Record. Book 94. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolrecord/94 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University of Chicago Law School Record by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTENTS SPRING 2006 3 Improving the Transition to Emancipation: Understanding, and solving, the problems facing foster youth aging out of the system The Law School's Foster Care Project, led by Professor Emily Buss, unites former foster children, scholars, policy makers, judges, and lawyers in an effort to understand the special problems facing foster youth aging out of the child welfare system. Story by Heidi Mueller, '07, photographs by Lloyd DeGrane. 6 Drawing Religious and Political Boundaries: Constitutional anti-sorting principles ''Anti-sorting principles are not anti-religion," writes Professor Adam M. Samaha. ''And they do not entail opposition to religion in politics." This article looks at anti-sorting principles as a welcome addition to our continuing search for the proper relationship between religion and political institutions. It is an excerpt from "Endorsement Retires: From Religious Symbols to Anti-sorting Principles" that first appeared in the 2005 Supreme Court Review.