Report of the Pan-Canadian Committee on Quality Assurance of Degree Programming: Quality Assurance of E-Learning and Private Institutions September 2006 Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CALENDAR 2006-07 “Teaching Each Other in All Wisdom” Colossians 1:28

CALENDAR 2006-07 “Teaching Each Other In All Wisdom” Colossians 1:28 9125-50 Street · Edmonton, Alberta, Canada · T6B 2H3 Telephone (780) 465-3500 ● Toll Free (Student Services Only) 1 (800) 661-TKUC(8582) ● Fax (780) 465-3534 EMail: [email protected] or [email protected] ● World Wide Web: www.kingsu.ca CONTACTS 2006-07 Requests for specific information should be directed to the following departments: Athletics Intercollegiate Sports E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (780)465-8345 Bookstore Textbooks and Other Books E-mail: [email protected] Clothing, Music, Cards Phone: (780)465-8306 Other Supplies Campus Minister Pastoral Care E-mail: [email protected] Spiritual Life Phone: (780)465-3500, ext. 8070 Central Office Services Mail Phone: (780)465-3500, ext. 8021 Photocopying Reception Conference Services Facility Rental E-mail: [email protected] Reservation of Rooms and Equipment Phone: (780)465-8323 Counsellor Personal Counselling E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (780)465-3500, ext. 8086 Dean of Students Non-academic Student Concerns E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (780)465-3500, ext. 8037 Development Alumni and Parent Relations E-mail: [email protected] Donations Phone: (780)465-8314 Fund-raising Programs Public Relations Enrolment Services Admissions Information and Counselling E-mail: [email protected] Campus Employment Phone: (780)465-8334 or 1-800-661-8582 Financial Aid Scholarships and Bursaries Facilities Building Operations E-mail: [email protected] Building Repairs and Renovations Phone: (780)465-3500, ext. 8363 Custodial Services Grounds Maintenance Parking Security and Safety Financial Services Accounting E-mail: [email protected] Financial Reports Employee Payroll Processing 2 Contacts Food Services Special Dietary Requirements E-mail: [email protected] Banquets and Catering Phone: (780)465-8305 Beverage Services Comments and Suggestions Human Resources Employee Payroll Commencement and Benefits E-mail: [email protected] Employment Opportunities Phone: (780)465-3500, ext. -

YORKVILLE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2021 Ontario

YORKVILLE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2021 Ontario Most recent revision: June 2021 * This document and the information it contains are the exclusive property of Yorkville University. It is provided to interested parties for information purposes only. This document cannot be copied, distributed, altered or modified in part or in whole, or used for any other purposes without prior written consent from Yorkville University. Academic Calendar CONTENTS 1. Academic Schedule / Important Dates ............................................................................ 6 2. Governance of the University ........................................................................................ 10 2.1 Board of Governors ................................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Academic Council ...................................................................................................................... 11 3. Vision and Mission ........................................................................................................ 12 3.1 Vision ......................................................................................................................................... 12 3.2 Mission ...................................................................................................................................... 12 3.3 Educational Objectives .............................................................................................................. 12 4. History -

Associate Dean, Faculty of Education (0.5 FTE)

Associate Dean, Faculty of Education (0.5 FTE) The Associate Dean leadership for planning, quality assurance, and academic operations, particularly with respect to: policies and procedures relating to curriculum and faculty aligned to the Master of Education in Adult Education (MEAE) or Master of Education Leadership (MEEL). The Associate Dean also provides support in faculty hiring, maintains faculty files, and oversees faculty development and faculty performance evaluation. The Associate Dean ensures effective communications and follow-up within the Faculty and University committee structure. The Associate Dean develops and maintains professional and academic connections to ensure programs are at the forefront of the discipline and profession of education. Please note - the successful candidates can be located in Fredericton, NB, or can work virtually. If located elsewhere than Fredericton, occasional travel to Fredericton is required, to be determined in consultation with the Dean. DUTIES AND RESPONSIBILITIES Academic Leadership With the Dean, contribute to curriculum planning and development Oversee performance review of faculty members Develop and present strategies and practices to improve instruction and student satisfaction Coordinate distribution of course evaluations to Faculty Academic Operations Membership on Faculty Hiring committee; ensure that new faculty members are effectively oriented to University policies, program goals, course objectives and pedagogy as well as the LMS Maintain faculty files as required by University -

Bachelor of Interior Design

Online + On-Campus Bachelor of Interior Design Change the world through design. www.yorkvilleu.ca Yorkville University is a Canadian About university with a national presence, offeringprofessional , practitioner- oriented programs. At Yorkville University, Yorkville students experience the flexibility needed to earn a degree while balancing other University commitments in a supportive, collaborative and interactive learning community. Program Overview The mission of the Bachelor of Interior Design program is to cultivate student knowledge, and foster exploratory and critical skills through educational experiences that are relevant to effectively meet the demands of their Change the future professional career and the betterment of society. World through The program is designed to: Teach you to apply critical, analytical and technical skills in high level design processes. Help you gain expertise in the latest technical and digital media. Develop creative and collaborative problem solving skills, visual literacy, cultural and ecological awareness. Grow a real understanding of the design industry’s business side and The Bachelor of Interior Design offers students the how to market yourself. opportunity to connect, collaborate, innovate and enhance the physical world around them through design. Designed for creative minds with a passion for aesthetics and function, the program lays the foundation to creating beautiful, practical, healthy and safe spaces. PROGRAM STRENGTHS I chose Yorkville University to realize my ambition INDUSTRY PROFESSIONALS SMALL CLASSES of being a globally accepted designer. Winning the AND NETWORKS On-campus and online IDEC Student Award confirmed I made the right Learn from instructors who are experienced, practicing courses maintain an average class size of 20 students YASAMAN SAEIDI professionals with active for personalized instructor Bachelor of Interior Design Graduate connections to the design feedback and a heightened industry and professional level of interaction. -

2011 D R Program POSTING

Ontario Student Loan Recipients and Defaults by Program for Other Public and Private Institutions in Ontario, 2011 INSTITUTION NAME PROGRAM NAME Number Number of of Loans Loans in Default Issued (1) Default (2) Rate (3) 2008/09 2011 2011 CANADA CHRISTIAN COLLEGE Bachelor Christian Counselling * * * Bachelor Of Sacred Music * * * Bachelor Of Theology * * * Master Of Divintiy ** * CANADA CHRISTIAN COLLEGE Total 6 2 33.3% * CANADIAN COLLEGE OF NATUROPATHIC MEDICINE Naturopathic Medicine 60 0 0.0% CANADIAN COLLEGE OF NATUROPATHIC MEDICINE Tota 60 0 0.0% * CANADIAN MEMORIAL CHIROPRACTIC COLLEGE Chiropractic Degree 102 1 1.0% CANADIAN MEMORIAL CHIROPRACTIC COLLEGE Tota 102 1 1.0% * CANADIAN MOTHERCRAFT SOCIETY Early Childhood Eduaction Diploma Program 10 1 10.0% CANADIAN MOTHERCRAFT SOCIETY Tota 10 1 10.0% COLLEGE D'ALFRED - University of Guelph Nutrition Et Salubrite Des Aliments 7 1 14.0% Technologie Agricole ** * COLLEGE D'ALFRED - University of Guelph Total 9 2 22.0% * COVENANT CANADIAN REFORMED TEACHERS' COLLEGE Diploma In Education * * * Diploma In Teaching * * * COVENANT CANADIAN REFORMED TEACHERS' COLLEGE Tota ** * * EASTERN ONTARIO SCH OF XRAY TECH X-Ray Technology ** * EASTERN ONTARIO SCH OF XRAY TECH Total ** * * EMMANUEL BIBLE COLLEGE Bachelor Of Theology * * * Bachelor Religious Education 5 1 20.0% Mountain Top Certificate 8 0 0.0% EMMANUEL BIBLE COLLEGE Total 16 1 6.3% * FOUNDATION FOR MONTESSORI EDUCATION A.M.I. Primary Teacher Training Pgm 6 0 0.0% FOUNDATION FOR MONTESSORI EDUCATION Total 6 0 0.0% Notes (1) Number of students at this institution who were issued an Ontario Student Loan (OSL) in 2008/09 and did not receive an OSL in 2009/10. -

Assessing the Influence of First Nation Education Counsellors on First Nation Post-Secondary Students and Their Program Choices

Assessing the Influence of First Nation Education Counsellors on First Nation Post-Secondary Students and their Program Choices by Pamela Williamson A dissertation submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Higher Education Graduate Department of Theory and Policy Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto © Copyright by Pamela Williamson (2011) Assessing the Influence of First Nation Education Counsellors on First Nation Post-Secondary Students and their Post-Secondary Program Choices Doctor of Higher Education 2011 Pamela Williamson Department of Theory and Policy Studies in Education University of Toronto Abstract The exploratory study focused on First Nation students and First Nation education counsellors within Ontario. Using an interpretative approach, the research sought to determine the relevance of the counsellors as a potentially influencing factor in the students‘ post-secondary program choices. The ability of First Nation education counsellors to be influential is a consequence of their role since they administer Post- Secondary Student Support Program (PSSSP) funding. A report evaluating the program completed by Indian and Northern Affairs Canada in 2005 found that many First Nation students would not have been able to achieve post-secondary educational levels without PSSSP support. Eight self-selected First Nation Education counsellors and twenty-nine First Nation post- secondary students participated in paper surveys, and five students and one counsellor agreed to complete a follow-up interview. The quantitative and qualitative results revealed differences in the perceptions of the two survey groups as to whether First Nation education counsellors influenced students‘ post-secondary program choices. -

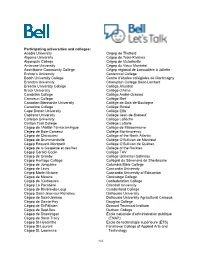

Participating Universities and Colleges: Acadia University Algoma University Algonquin College Ambrose University Assiniboine C

Participating universities and colleges: Acadia University Cégep de Thetford Algoma University Cégep de Trois-Rivières Algonquin College Cégep de Victoriaville Ambrose University Cégep du Vieux Montréal Assiniboine Community College Cégep régional de Lanaudière à Joliette Bishop’s University Centennial College Booth University College Centre d'études collégiales de Montmagny Brandon University Champlain College Saint-Lambert Brescia University College Collège Ahuntsic Brock University Collège d’Alma Cambrian College Collège André-Grasset Camosun College Collège Bart Canadian Mennonite University Collège de Bois-de-Boulogne Canadore College Collège Boréal Cape Breton University Collège Ellis Capilano University Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf Carleton University Collège Laflèche Carlton Trail College Collège LaSalle Cégep de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue Collège de Maisonneuve Cégep de Baie-Comeau Collège Montmorency Cégep de Chicoutimi College of the North Atlantic Cégep de Drummondville Collège O’Sullivan de Montréal Cégep Édouard-Montpetit Collège O’Sullivan de Québec Cégep de la Gaspésie et des Îles College of the Rockies Cégep Gérald-Godin Collège TAV Cégep de Granby Collège Universel Gatineau Cégep Heritage College Collégial du Séminaire de Sherbrooke Cégep de Jonquière Columbia Bible College Cégep de Lévis Concordia University Cégep Marie-Victorin Concordia University of Edmonton Cégep de Matane Conestoga College Cégep de l’Outaouais Confederation College Cégep La Pocatière Crandall University Cégep de Rivière-du-Loup Cumberland College Cégep Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu Dalhousie University Cégep de Saint-Jérôme Dalhousie University Agricultural Campus Cégep de Sainte-Foy Douglas College Cégep de St-Félicien Dumont Technical Institute Cégep de Sept-Îles Durham College Cégep de Shawinigan École nationale d’administration publique Cégep de Sorel-Tracy (ENAP) Cégep St-Hyacinthe École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS) Cégep St-Laurent Fanshawe College of Applied Arts and Cégep St. -

YORKVILLE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2020 British Columbia

YORKVILLE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2020 British Columbia Most recent revision: December 2020 * This document and the information it contains are the exclusive property of Yorkville University. It is provided to interested parties for information purposes only. This document cannot be copied, distributed, altered or modified in part or in whole, or used for any other purposes without prior written consent from Yorkville University. * The term “university” is used under the written consent of the Minister of Advanced Education effective August 12, 2015 having undergone a quality assessment process and been found to meet the criteria established by the minister. Academic Calendar CONTENTS 1. Academic Schedule / Important Dates .............................................................................. 1 2. Governance of the University ........................................................................................... 5 2.1 Board of Governors ..................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Academic Council ........................................................................................................................ 6 3. Vision and Mission ........................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Vision ........................................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Mission ....................................................................................................................................... -

MISSIONFEST TORONTO • 2007 1 Artech Communications Inc

MISSIONFEST TORONTO • 2007 1 Artech Communications Inc. has for over 14 years been helping Christian’s communicate! Whether you’re hosting a conference or event, building a new church or filming missions on the other side of the world, we are here to serve you. We have served approximately 2000+ Christian organizations and hundreds of secular ones as well. We offer: - “Best-in-class” equipment – sales, service and rental - Audio, video, lighting - consulting and design services - Professional audio, video and lighting engineers - Installation services for audio, video, lighting, drape, chairs, staging and more - Web hosting and web streaming services - Concert and event services - Conferences, tradeshows and meetings Artech Communications Inc. has provided design and installation services for over 600 new church and major renovation projects. We have helped facilitate denominational meetings, conferences, concerts, tradeshows and events in large and small venues, both indoors and outdoors. We would truly appreciate the opportunity to serve you. ARTS | TECHNOLOGY | COMMUNICATIONS 3184 Ridgeway Dr. Unit 43 Mississauga | ON | L5L 5S7 866.520.0514 | 905.820.0514 [email protected] www.artechcommunications.com 2 MISSIONFEST TORONTO • 2007 MISSIONFEST TORONTO • 2007 3 2007 MFTV Full Page Ad.indd 1 12/4/06 10:11:20 PM HELP US HELP THEM ��������������������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������������������������ ���������������������������������������������������������� -

Hon. Ross Romano Minister of Colleges and Universities Ministry of Colleges and Universities 5Th Floor, 438 University Ave Toronto, on M7A 2A5 October 22, 2020

Hon. Ross Romano Minister of Colleges and Universities Ministry of Colleges and Universities 5th Floor, 438 University Ave Toronto, ON M7A 2A5 October 22, 2020 Dear Minister Romano, I am contacting you on behalf of the Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations (OCUFA), which represents 17,000 faculty and academic librarians across the province. We are alarmed that your government is intending to discreetly pass legislation that would allow the Canada Christian College to call itself a “university” and award degrees. Broadly, we are concerned about emerging efforts to privatize postsecondary education in Ontario and to give private institutions degree-granting privileges that will undermine the quality and accessibility of postsecondary education in Ontario. This is especially evident in the case of Canada Christian College where Charles McVety, who runs the college, openly holds deeply rooted Islamophobic, transphobic, and homophobic views. McVety has been embroiled in several controversies resulting from his discriminatory beliefs. We will not repeat any of his bigotry in our letter; it is well documented. The Ontario government should not grant accreditation and degree-granting privileges to institutions that do not meet the anti-discriminatory and anti-hate speech principles outlined in the Ontario Human Rights Code. It is imperative that the government protect religious minorities, the queer community, and other marginalized groups. At the very least, the government should do no harm. Allowing the Canada Christian College to call itself a “university” and to award degrees in our province would most certainly harm these marginalized communities and allow hateful and discriminatory speech to persist. Your Ministry must change course on this urgent matter. -

Top Colleges & Universities in Canada | 2012 University Web

Top Colleges & Universities in Canada | 2012 University Web Rankings http://www.4icu.org/ca/ > North America > Universities in Canada List of top Colleges and Universities in Canada by university web ranking. Link to it ♥ UNIVERSITIES IN CANADA by 2012 University Web Ranking 搜索 Search Canadian Universities websites Ads by Google ITT Tech - Official Site Tech-Oriented Degree Programs. Education for the Future. www.ITT-Tech.edu Universities Locations 1 University of Toronto Toronto 2 The University of British Columbia Vancouver ... 3 McGill University Montreal ... 4 University of Waterloo Waterloo 5 University of Alberta Edmonton ... 6 Simon Fraser University Burnaby ... 7 York University Toronto 8 University of Calgary Calgary 9 University of Victoria Victoria 10 Queen's University Kingston 11 Université de Montréal Montreal 12 The University of Western Ontario London 13 Université Laval Quebec City 14 University of Ottawa Ottawa 15 University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon 16 University of Guelph Guelph ... 17 Université du Québec à Montréal Montréal ... 18 McMaster University Hamilton 1 of 4 11/10/2012 2:54 PM Top Colleges & Universities in Canada | 2012 University Web Rankings http://www.4icu.org/ca/ 19 Université de Sherbrooke Sherbrooke ... 20 Carleton University Ottawa 21 Dalhousie University Halifax 22 Concordia University Montreal 23 University of Manitoba Winnipeg 24 Ryerson University Toronto 25 Memorial University of Newfoundland St John’s ... 26 University of New Brunswick Fredericton ... 27 University of Regina Regina 28 University of Winnipeg Winnipeg 29 Brock University St. Catharines ... 30 British Columbia Institute of Technology Burnaby 31 University of Windsor Windsor 32 HEC Montréal Montreal 33 Université du Québec Quebec City .. -

Les Outils D'aide À La Traduction Comme Pratique Normative Et La

Les outils d’aide à la traduction comme pratique normative et la formation subséquente des traducteurs professionnels au Canada Catherine Landreville Mémoire présenté au Département d’études françaises comme exigence partielle au grade de maîtrise ès arts (en traductologie) Université Concordia Montréal, Québec, Canada Septembre 2018 © Catherine Landreville, 2018 UNIVERSITÉ CONCORDIA École des études supérieures Nous certifions par la présente que le mémoire rédigé par Catherine Landreville intitulé Les outils d’aide à la traduction comme pratique normative et la formation subséquente des traducteurs professionnels au Canada et déposé à titre d’exigence partielle en vue de l’obtention du grade de Maîtrise ès Arts (Traductologie) est conforme aux règlements de l’Université et satisfait aux normes établies pour ce qui est de l’originalité et de la qualité. Signé par les membres du Comité de soutenance Président Paul Bandia, Université Concordia Examinateur Philippe Caignon, Université Concordia Examinatrice Elizabeth Marshman, Université d’Ottawa Directrice Deborah Folaron, Université Concordia Approuvé par : Directeur du département ou du programme d’études supérieures 2018 Doyen de la Faculté RÉSUMÉ Les outils d’aide à la traduction comme pratique normative et la formation subséquente des traducteurs professionnels au Canada Catherine Landreville On a longtemps prêté au Canada un statut particulier en matière de traduction en raison de sa réalité linguistique, mais également de sa politique linguistique bien ancrée. L’histoire de la création du Bureau de la traduction n’est plus à faire (Delisle, 2016), et de nombreux chercheurs se sont déjà penchés sur la structuration et l’uniformisation de l’enseignement de la traduction au Canada (dont Mareschal, 2005).