Assessing the Influence of First Nation Education Counsellors on First Nation Post-Secondary Students and Their Program Choices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IV. Admission Information | 2016-2017

2016-2017 Undergraduate Calendar The information published in this Undergraduate Calendar outlines the rules, regulations, curricula, programs and fees for the 2016-2017 academic year, including the Summer Semester 2016, the Fall Semester 2016 and the Winter Semester 2017. For your convenience the Undergraduate Calendar is available in PDF format. If you wish to link to the Undergraduate Calendar please refer to the Linking Guidelines. The University is a full member of: · The Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada Contact Information: University of Guelph Guelph, Ontario, Canada N1G 2W1 519-824-4120 http://www.uoguelph.ca Revision Information: Date Description February 1, 2016 Initial Publication February 3, 2016 Second Publication March 4, 2016 Third Publication April 5, 2016 Fourth Publication July 5, 2016 Fifth Publication August 25, 2016 Sixth Publication September 21, 2016 Seventh Publication January 12, 2017 Eighth Publication January 31, 2017 Ninth Publication Disclaimer University of Guelph 2016 The information published in this Undergraduate Calendar outlines the rules, regulations, curricula, programs and fees for the 2016-2017 academic year, including the Summer Semester 2016, the Fall Semester 2016 and the Winter Semester 2017. The University reserves the right to change without notice any information contained in this calendar, including fees, any rule or regulation pertaining to the standards for admission to, the requirements for the continuation of study in, and the requirements for the granting of degrees or diplomas in any or all of its programs. The publication of information in this calendar does not bind the University to the provision of courses, programs, schedules of studies, or facilities as listed herein. -

CALENDAR 2006-07 “Teaching Each Other in All Wisdom” Colossians 1:28

CALENDAR 2006-07 “Teaching Each Other In All Wisdom” Colossians 1:28 9125-50 Street · Edmonton, Alberta, Canada · T6B 2H3 Telephone (780) 465-3500 ● Toll Free (Student Services Only) 1 (800) 661-TKUC(8582) ● Fax (780) 465-3534 EMail: [email protected] or [email protected] ● World Wide Web: www.kingsu.ca CONTACTS 2006-07 Requests for specific information should be directed to the following departments: Athletics Intercollegiate Sports E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (780)465-8345 Bookstore Textbooks and Other Books E-mail: [email protected] Clothing, Music, Cards Phone: (780)465-8306 Other Supplies Campus Minister Pastoral Care E-mail: [email protected] Spiritual Life Phone: (780)465-3500, ext. 8070 Central Office Services Mail Phone: (780)465-3500, ext. 8021 Photocopying Reception Conference Services Facility Rental E-mail: [email protected] Reservation of Rooms and Equipment Phone: (780)465-8323 Counsellor Personal Counselling E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (780)465-3500, ext. 8086 Dean of Students Non-academic Student Concerns E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (780)465-3500, ext. 8037 Development Alumni and Parent Relations E-mail: [email protected] Donations Phone: (780)465-8314 Fund-raising Programs Public Relations Enrolment Services Admissions Information and Counselling E-mail: [email protected] Campus Employment Phone: (780)465-8334 or 1-800-661-8582 Financial Aid Scholarships and Bursaries Facilities Building Operations E-mail: [email protected] Building Repairs and Renovations Phone: (780)465-3500, ext. 8363 Custodial Services Grounds Maintenance Parking Security and Safety Financial Services Accounting E-mail: [email protected] Financial Reports Employee Payroll Processing 2 Contacts Food Services Special Dietary Requirements E-mail: [email protected] Banquets and Catering Phone: (780)465-8305 Beverage Services Comments and Suggestions Human Resources Employee Payroll Commencement and Benefits E-mail: [email protected] Employment Opportunities Phone: (780)465-3500, ext. -

2011 D R Program POSTING

Ontario Student Loan Recipients and Defaults by Program for Other Public and Private Institutions in Ontario, 2011 INSTITUTION NAME PROGRAM NAME Number Number of of Loans Loans in Default Issued (1) Default (2) Rate (3) 2008/09 2011 2011 CANADA CHRISTIAN COLLEGE Bachelor Christian Counselling * * * Bachelor Of Sacred Music * * * Bachelor Of Theology * * * Master Of Divintiy ** * CANADA CHRISTIAN COLLEGE Total 6 2 33.3% * CANADIAN COLLEGE OF NATUROPATHIC MEDICINE Naturopathic Medicine 60 0 0.0% CANADIAN COLLEGE OF NATUROPATHIC MEDICINE Tota 60 0 0.0% * CANADIAN MEMORIAL CHIROPRACTIC COLLEGE Chiropractic Degree 102 1 1.0% CANADIAN MEMORIAL CHIROPRACTIC COLLEGE Tota 102 1 1.0% * CANADIAN MOTHERCRAFT SOCIETY Early Childhood Eduaction Diploma Program 10 1 10.0% CANADIAN MOTHERCRAFT SOCIETY Tota 10 1 10.0% COLLEGE D'ALFRED - University of Guelph Nutrition Et Salubrite Des Aliments 7 1 14.0% Technologie Agricole ** * COLLEGE D'ALFRED - University of Guelph Total 9 2 22.0% * COVENANT CANADIAN REFORMED TEACHERS' COLLEGE Diploma In Education * * * Diploma In Teaching * * * COVENANT CANADIAN REFORMED TEACHERS' COLLEGE Tota ** * * EASTERN ONTARIO SCH OF XRAY TECH X-Ray Technology ** * EASTERN ONTARIO SCH OF XRAY TECH Total ** * * EMMANUEL BIBLE COLLEGE Bachelor Of Theology * * * Bachelor Religious Education 5 1 20.0% Mountain Top Certificate 8 0 0.0% EMMANUEL BIBLE COLLEGE Total 16 1 6.3% * FOUNDATION FOR MONTESSORI EDUCATION A.M.I. Primary Teacher Training Pgm 6 0 0.0% FOUNDATION FOR MONTESSORI EDUCATION Total 6 0 0.0% Notes (1) Number of students at this institution who were issued an Ontario Student Loan (OSL) in 2008/09 and did not receive an OSL in 2009/10. -

Fnti Student Handbook 2020/2021

FNTI STUDENT HANDBOOK 2020/2021 Mission To share unique educational experiences, rooted in Indigenous knowledge, thereby enhancing the strength of learners and communities. Vision Healthy, prosperous, and vibrant learners and communities through transformative learning experiences built on a foundation of Indigenous knowledge Motto Sharing and Learning 2 Table of Contents Words of Welcome 4 Contact Information 5 Rights of the Student 6 Responsibilities of FNTI 7 Responsibilities of Student 9 Program Information 10 Placement 11 Fees Information 12 Policy: Student Conduct, Behaviour and Discipline 14 Policy: Program Progression 18 Policy: Class Cancellation 19 3 Words of Welcome To Our Valued Students, Welcome to the FNTI Family, a strong network of 4,000+ members who have come together over the past 35 years. This is our 35th year of delivering quality post-secondary programs rooted in culture and Indigenous ways of knowing in partnership with recognized Ontario colleges and universities. Our unique model of braiding teaching, learning and healing in the classroom allows our students to fulfill personal and professional goals while maintaining connections to family and community while studying. We support our learners through their educational journey and through the process of deepening their Indigeneity. The world has changed dramatically since March, however FNTI remains committed to these key principles. Our new virtual environment allows us to maintain uninterrupted, culturally- rooted programming across Ontario. It has been built with you in mind, and our faculty, cultural advisors and student success facilitators are eager to support you through this exciting and unprecedented chapter. Once again, my sincerest congratulations on choosing to study at FNTI this year! Best regards, Suzanne Katsi'tsiarihshion Brant President 4 CONTACT INFORMATION Main Campus/Head Office 3 Old York Road Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory, ON K0K 1X0 Local: 613-396-2122 Toll Free: 800-267-0637 Fax: 613-396-2761 Hours of Operation 8:30 a.m. -

Digital Fluency Expression of Interest

January 6, 2021 Digital Fluency Expression of Interest Please review the attached document and submit your application electronically according to the guidelines provided by 11:59 pm EST on February 3, 2021. Applications will not be accepted unless: • Submitted electronically according to the instructions. Submission by any other form such as email, facsimiles or paper copy mail will not be accepted. • Received by the date and time specified. Key Dates: Date Description January 6, 2021 Expression of Interest Released Closing Date and Time for Submissions February 3, 2021 Submissions received after the closing date and 11:59pm EST time will not be considered for evaluation Submit applications here By February 28, 2021 Successful applicants notified Please note: due to the volume of submissions received, unsuccessful applicants will not be notified. Feedback will not be provided eCampusOntario will not be held responsible for documents that are not submitted in accordance with the above instructions NOTE: Awards for this EOI are contingent upon funding from MCU. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................... 3 2. DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................................................... 4 WHAT IS DIGITAL FLUENCY? .......................................................................................................... 4 3. PROJECT TYPE ..................................................................................................................... -

TOXIC WATER: the KASHECHEWAN STORY Introduction It Was the Straw That Broke the Prover- Had Been Under a Boil-Water Alert on and Focus Bial Camel’S Back

TOXIC WATER: THE KASHECHEWAN STORY Introduction It was the straw that broke the prover- had been under a boil-water alert on and Focus bial camel’s back. A fax arrived from off for years. In fall 2005, Canadi- Health Canada (www.hc-sc.gc.ca) at the A week after the water tested positive ans were stunned to hear of the Kashechewan First Nations council for E. coli, Indian Affairs Minister appalling living office, revealing that E. coli had been Andy Scott arrived in Kashechewan. He conditions on the detected in the reserve’s drinking water. offered to provide the people with more Kashechewan First Enough was enough. A community bottled water but little else. Incensed by Nations Reserve in already plagued by poverty and unem- Scott’s apparent indifference, the Northern Ontario. ployment was now being poisoned by community redoubled their efforts, Initial reports documented the its own water supply. Something putting pressure on the provincial and presence of E. coli needed to be done, and some members federal governments to evacuate those in the reserve’s of the reserve had a plan. First they who were suffering from the effects of drinking water. closed down the schools. Next, they the contaminated water. The Ontario This was followed called a meeting of concerned members government pointed the finger at Ot- by news of poverty and despair, a of the community. Then they launched tawa because the federal government is reflection of a a media campaign that shifted the responsible for Canada’s First Nations. standard of living national spotlight onto the horrendous Ottawa pointed the finger back at the that many thought conditions in this remote, Northern province, saying that water safety and unimaginable in Ontario reserve. -

Improving Community Housing, an Important Determinant of Health Through Mechanical and Electrical Training Programs

IMPROVING COMMUNITY HOUSING, AN IMPORTANT DETERMINANT OF HEALTH THROUGH MECHANICAL AND ELECTRICAL TRAINING PROGRAMS Leonard J.S. Tsuji Guy Iannucci Department of Environment Fort Albany First Nation and and Resource Studies RTllnc. University of Waterloo Fort Albany, Ontario Waterloo, Ontario Canada, POL 1HO Canada, N2L 3G1 Anthony Iannucci Fort Albany First Nation and RTllnc. Fort Albany, Ontario Canada, POL 1HO Abstract I Resume Until recently, "status quo" houses (Le., dwellings with no running water, washrooms, proper kitchens, or adequate electrical services) were typically built in First Nations (FN). We describe a training program that upgraded existing status quo homes in Fort Albany First Nation to a level comparable to the rest of Canada, on a limited budget. The program provided not only an educational experience for the stUdents, but also paid employment for Fort Albany First Nation members, as well as long-term community benefits. Jusqu'a, a present, les maisons "statu quo", (c.a.d.les habitations sans eau courante, sans toilettes, sans cuisines appropriees et sans electricite adequate), ont ete typiquement construites dans Ie Premiere Nations. Nous decrivons un programme de formation qui, avec un budget limite, a permis d'ameliorer les maisons "statu quo" dans les Premieres Nations, Fort Albany, a un niveau comparable au reste du Canada. Ce programme a non seulement fourni une experience educative aux etudiants, mais a egale ment cree des emplois remuneres aux membres des Premieres Nations, Fort Albany et a demontre des avantages a long terme pourla communaute. The Canadian Journal ofNative Studies XX, 2(2000):251-261. 252 Leonard J.S. -

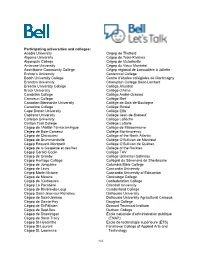

Participating Universities and Colleges: Acadia University Algoma University Algonquin College Ambrose University Assiniboine C

Participating universities and colleges: Acadia University Cégep de Thetford Algoma University Cégep de Trois-Rivières Algonquin College Cégep de Victoriaville Ambrose University Cégep du Vieux Montréal Assiniboine Community College Cégep régional de Lanaudière à Joliette Bishop’s University Centennial College Booth University College Centre d'études collégiales de Montmagny Brandon University Champlain College Saint-Lambert Brescia University College Collège Ahuntsic Brock University Collège d’Alma Cambrian College Collège André-Grasset Camosun College Collège Bart Canadian Mennonite University Collège de Bois-de-Boulogne Canadore College Collège Boréal Cape Breton University Collège Ellis Capilano University Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf Carleton University Collège Laflèche Carlton Trail College Collège LaSalle Cégep de l’Abitibi-Témiscamingue Collège de Maisonneuve Cégep de Baie-Comeau Collège Montmorency Cégep de Chicoutimi College of the North Atlantic Cégep de Drummondville Collège O’Sullivan de Montréal Cégep Édouard-Montpetit Collège O’Sullivan de Québec Cégep de la Gaspésie et des Îles College of the Rockies Cégep Gérald-Godin Collège TAV Cégep de Granby Collège Universel Gatineau Cégep Heritage College Collégial du Séminaire de Sherbrooke Cégep de Jonquière Columbia Bible College Cégep de Lévis Concordia University Cégep Marie-Victorin Concordia University of Edmonton Cégep de Matane Conestoga College Cégep de l’Outaouais Confederation College Cégep La Pocatière Crandall University Cégep de Rivière-du-Loup Cumberland College Cégep Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu Dalhousie University Cégep de Saint-Jérôme Dalhousie University Agricultural Campus Cégep de Sainte-Foy Douglas College Cégep de St-Félicien Dumont Technical Institute Cégep de Sept-Îles Durham College Cégep de Shawinigan École nationale d’administration publique Cégep de Sorel-Tracy (ENAP) Cégep St-Hyacinthe École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS) Cégep St-Laurent Fanshawe College of Applied Arts and Cégep St. -

The 2009 H1N1 Health Sector Pandemic Response in Remote and Isolated First Nation Communities of Sub-Arctic Ontario, Canada

The 2009 H1N1 Health Sector Pandemic Response in Remote and Isolated First Nation Communities of Sub-Arctic Ontario, Canada by Nadia A. Charania A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Environmental Studies in Environment and Resource Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Nadia A. Charania 2011 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii ABSTRACT On June 11, 2009, the World Health Organization declared a global influenza pandemic due to a novel influenza A virus subtype of H1N1. Public health emergencies, such as an influenza pandemic, can potentially impact disadvantaged populations disproportionately due to underlying social factors. Canada‟s First Nation population was severely impacted by the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Most First Nation communities suffer from poor living conditions, impoverished lifestyles, lack of access to adequate health care, and uncoordinated health care delivery. Also, there are vulnerable populations who suffer from co-morbidities who are at a greater risk of falling ill. Moreover, First Nation communities that are geographically remote (nearest service center with year-round road access is located over 350 kilometers away) and isolated (only accessible by planes year-round) face additional challenges. For example, transportation of supplies and resources may be limited, especially during extreme weather conditions. Therefore, remote and isolated First Nation communities face unique challenges which must be addressed by policy planners in order to mitigate the injustice that may occur during a public health emergency. -

Annual Report 2016-17 Table of Contents Message from the Board Co-Chairs

Annual Report 2016-17 Table of Contents Message from the Board Co-Chairs........................... 01 Mobility Infrastructure.................................................... 21 Message from the Executive Director........................ 04 Pathway Development Why Mobility Matters..................................................... 07 Knowledge Gathering Who We Are Learning Outcomes Strategic Priorities Transfer Banter................................................................. 25 Our Partners Committees...................................................................... 29 Students First................................................................... 11 Board of Directors.......................................................... 31 Building on Shared Resources..................................... 17 The ONCAT Team........................................................... 32 Bringing Our Identity Full Circle Platforms for Collaboration ONTransfer.ca Website Redesign Message from the Board Co-Chairs This is an exciting year for the postsecondary system serving on ONCAT’s Board of Directors, it really has been and one in which Ontario’s colleges celebrate their a pleasure to be involved with an organization committed 50th anniversary. Throughout these past decades, to not only supporting the partnership aspirations of postsecondary education as a system and the relationship institutions, but also involving students and government in of colleges and universities, has evolved to one of a collective effort to expand student -

First Nation – Child Care and Child and Family Program Contact List (July 2019)

First Nation – Child Care and Child and Family Program Contact List (July 2019) First Nations & Transfer Payment Agencies (TPAs) EYA Financial Analyst Aamjiwnaang First Nation Nathalie Justin Alderville First Nation Natasha Bryan Algonquins of Pikwakanagain First Nation Rachelle Danielle Animbiigoo Zaagi’igan Anishinaabek Kelly Agnes Animakee Wa Zhing 37 (Northwest Angle 37) First Nation Kelly Bryan Anishinabe of Wauzhushk Onigum First Nation Kelly Argen Aroland First Nation Kelly Argen Asubpeeschoseewagon netum Anishnabek-Grassy Narrows Kelly Agnes First Nation Attawapiskat First Nation Lina Argen Atikameksheng Anishnabek (Whitefish Lake) Lina David Aundeck-Omni-Kaning First Nation Lina Vanessa Batchewana (Rankin) First Nation Lina David Bearskin Lake First Nation Kelly Agnes Beausoleil First Nation (Christian Island) Maria David Big Grassy River First Nation Isilda Vanessa Cat Lake First Nation Kelly Danielle Chippewas of Georgina Island Maria Bryan Chippewas of Kettle & Stony Point First Nation Nathalie Justin Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation Nathalie Bryan Chippewas of Rama First Nation Maria Bryan Chippewas of Saugeen First Nation Nathalie Bryan Chippewas of the Thames First Nation Karen Justin Constance Lake First Nation Lina Argen Couchiching First Nation Kelly Argen Curve Lake First Nation Natasha Bryan Deer Lake First Nation Kelly Agnes Delaware Nation Council Moravian of the Thames Band Nathalie Justin Eabametoong First Nation Kelly Agnes Eagle Lake First Nation Kelly Agnes Firefly Kelly Bryan 1 First Nations & Transfer -

AFN Renewal Commission : Recommendations 2005

AFN Renewal Commission Report of Recommendations 2005 A Treaty Among Ourselves Returning to the Spirit of Our Peoples AFN Renewal Commission Report 2005 Assembly of First Nations Renewal Commission 473 Albert Street, 8th floor, Ottawa, ON K1R 5B4 (613) 241-6789 • toll-free: 1-866-869-6789 www.afn.ca Table of Contents table of . contents. Letter of Transmittal 1 Preamble . 2 Introduction . 5 Background . 5 Mandate and Methodology . 5 Report Structure . 6 Chapter 1 - Our Shared Vision of Renewal AFN Renewal Vision . 7 AFN Renewal Framework. 8 Why is AFN Renewal Required?. 9 Implementing the Recommendations to Achieve the Vision . 13 Renewal is an Honourable Goal . 14 Chapter 2 - An AFN Rooted in Culture: Respect For First Nation Values Introduction . 15 Issue: First Nation Values . 17 Issue: Traditional Leadership and Decision-Making Practices . 18 Issue: First Nation Traditional and Cultural Practices and Languages . 19 Chapter 3 - Making the AFN Representative Introduction . 21 Issue: Defining AFN Membership . 22 Issue: Exercising the Rights of Membership . 23 Issue: Representation of Individual First Nation Citizens and Urban First Nation Organizations . 25 Issue: National Election . 27 Issue: Relationships with Other First Nation Organizations . 30 Issue: Effective Representation in National Forums . 32 Issue: Effective Representation in International Forums. 33 Issue: Support for Nation-Building . 36 Chapter 4 - A Responsive AFN: Renewing AFN Governing & Corporate Structures Introduction. 39 Issue: Treaties . 41 Issue: AFN Assembly Structures. 43 First Nations-in-Assembly. 43 The Confederacy of Nations . 43 Issue: Executive Structures . 45 The AFN Executive Committee . 45 The National Chief . 48 AFN Regional Chiefs . 50 Issue: Advisory Structures (Councils: Elders, Women, Youth) .