Claims Resolution Tribunal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainable Urban Mobility and Public Transport in Unece Capitals

UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE SUSTAINABLE URBAN MOBILITY AND PUBLIC TRANSPORT IN UNECE CAPITALS UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE SUSTAINABLE URBAN MOBILITY AND PUBLIC TRANSPORT IN UNECE CAPITALS This publication is part of the Transport Trends and Economics Series (WP.5) New York and Geneva, 2015 ©2015 United Nations All rights reserved worldwide Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the Copyright Clearance Center at copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: United Nations Publications, 300 East 42nd St, New York, NY 10017, United States of America. Email: [email protected]; website: un.org/publications United Nations’ publication issued by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Maps and country reports are only for information purposes. Acknowledgements The study was prepared by Mr. Konstantinos Alexopoulos and Mr. Lukasz Wyrowski. The authors worked under the guidance of and benefited from significant contributions by Dr. Eva Molnar, Director of UNECE Sustainable Transport Division and Mr. Miodrag Pesut, Chief of Transport Facilitation and Economics Section. ECE/TRANS/245 Transport in UNECE The UNECE Sustainable Transport Division is the secretariat of the Inland Transport Committee (ITC) and the ECOSOC Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods and on the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals. -

D4 Jarovce – Ivanka North Final Opinion

D4 Highway, Jarovce - Ivanka North FINAL OPINION (No: 318/2010-3.4/ml) issued by the Slovak Ministry of Environment under Act no. 24/2006 Coll. on the assessment of impacts on the environment and on amendments to certain acts, as amended. I. BASIC INFORMATION ON CLAIMANT 1. Name Národná diaľničná spoločnosť, a.s. 2. ID No. 35 919 001 3. Registered Office Mlynské Nivy 45, 821 09 Bratislava II. BASIC INFORMATION ON THE PROPOSED ACTIVITY 1. Name D4 Highway, Jarovce - Ivanka North. 2. Purpose of the project The purpose of the proposed activity is to ensure road linking of existing highway routes D1 and D2 in the southern, eastern and northern part of the City of Bratislava and international interconnection of Slovakia and Austria with transport links to Hungary and the Czech Republic. 3. User Motor public. 4. Location (cadastral area) Region: Bratislava District: Bratislava II, Bratislava V , Senec Municipality: Bratislava, Most pri Bratislave, Ivanka pri Dunaji Cadastral area: Bratislava – district of Jarovce, Rusovce, Podunajské Biskupice and Vajnory, Most pri Bratislave, Ivanka pri Dunaji - Farná, Ivanka pri Dunaji, 5. Dates of Commencement and Completion of the Construction and Operation of the Proposed Works Date of Commencement of Works: 2014 Date of Completion of Works: 2018 Date of Operation: 2018 Estimated year of closure: unkonwn 6. Brief description of technical and technological solutions Baseline situation and objectives Transport in Bratislava is currently (baseline situation) unbearable. This is because of the morning and evening -

Transport Node of Bratislava in Relationship with Pan-European Multimodal Corridors Marcel HORŇÁK, Zuzana KOVÁČIKOVÁ

Transport Node of Bratislava in Relationship with Pan-European Multimodal Corridors Marcel HORŇÁK, Zuzana KOVÁČIKOVÁ Abstract Bratislava as a capital of the Slovak Republic plays a special role in transport network of Slovakia. This peculiarity is a consequence of several geographical circumstances: eccentric and border position in the state, closeness of Vienna, natural conditions as well as intraurban and spatial structure of the city and its specific development. In 1990s, Bratislava became a point of intersection of three pan- European transport corridors which has brought a new impulses to the city. Key words: pan-European transport corridor, transport node Introduction Change of political and economic orientation of central and eastern Europe countries brought a demand to extend and link the transport network working in west Europe towards these countries, with an aim to create a pan-European transport network. Four of the ten pan-European multimodal corridors defined in Crete and Helsinki in 1994 and 1997 for the territory of central and eastern Europe cross the area of the Slovak Republic. Bratislava is an intersection point of three of these multimodal corridors (see Fig. 1): ¾ Corridor IV connecting Berlin/Nürnberg – Prague – Budapest – Constanta – Thessaloniki – Istanbul, ¾ Corridor VA connecting Bratislava – Žilina – Košice – Uzhorod - Lviv, ¾ Corridor VII – the Danube. Defining the multimodal corridors means a concentration of investments into trasport infrastructure aimed to construction of an efficient trans-European network being able to increase opportunities to cross borders and develop economies. The corridors are also a direct contribution to the pan-European integration and give a new start to the development of the central and eastern Europe. -

Travel Booklet How to Get to Brno Welcome

TRAVEL BOOKLET HOW TO GET TO BRNO WELCOME Let us officially welcome you on board of this summer adventure,85th International Session of the Eu- ropean Youth Parliament – Brno 2017. Brno, the host city of the session, is the Czech Republic’s second largest city. This young university town with a rich historical heritage is of immense administrative and cultural importance to the country. Travelling to this conveniently located city should not be anything but enjoyable. We are more than happy to assist you with booking your tickets. Should you have any questions, do not hesitate to contact us at [email protected]. TRAVEL FORM This Travel Booklet serves as a guide that should help you to successfully submit the Travel Form. Please do fill it in by Monday, 1 May 2017. Note that in order to complete the Travel Form, you will not only need to book your tickets, but also fill in and scan other documents, such as the Consent Form (for participants under 18 or participants over 18, and the Medical Emergency Sheet). ARRIVALS You are expected to arrive in Brno until the evening of Friday, 21 July 2017. We recommend you to arrive in Prague or any of the nearby cities (Vienna, Bratislava) at 17:00 latest in order to get to Brno in a timely manner. Organisers will be waiting to pick you up from the Brno Main Train HANDY TIP Station, the Brno Grand bus terminal and also the Brno ÚAN NUMBER 1 Zvonařka bus terminal, therefore there is no need to worry about transport within Brno itself. -

BRATISLAVA and VIENNA: Twin Cities with Big Potentials

SEPTEMBER 2018 Policy Notes and Reports BRATISLAVA and VIENNA: Twin Cities with big Potentials Doris Hanzl-Weiss, Mario Holzner and Roman Römisch The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies Wiener Institut für Internationale Wirtschaftsvergleiche BRATISLAVA and VIENNA: Twin Cities with big Potentials DORIS HANZL-WEISS MARIO HOLZNER ROMAN RÖMISCH Doris Hanzl-Weiss is Economist at The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw). Mario Holzner is Deputy Scientific Director of wiiw. Roman Römisch is Economist at wiiw. Abstract The economies of Vienna and Bratislava have seen quite a different development over the last decades. While Vienna’s population increased by about 20% within two decades, Bratislava’s population mostly stagnated. However, measured in GDP per capita at purchasing power parties, average income in Bratislava has surpassed that of Vienna and is now among the top-10 leading regions in Europe. Massive foreign direct investment, particularly in the automotive sector, has caused full employment in Bratislava. Nevertheless, Vienna as one of the world’s most liveable cities is still attracting more immigration and labour markets are in less favourable conditions. Transport infrastructure between the two close cities has been improving only recently which leaves considerable scope for further reductions in travel time. Regional cooperation is under way and should be reinforced in order to meet the challenges ahead. Mass-emigration of young Slovaks over the last decades will lead to a rapid ageing in Slovakia over the next decades and the working age population is expected to shrink by almost a third by the end of the century, while Austria’s will mostly stagnate. -

Bratislava Destination Guide

EN 9 5 8 7 6 4 10 2 CENTRUM 3 1 11 Bratislava Destination Guide Bratislava Tourist Board Primaciálne nám. 1 11 P. O. BOX 349 810 00 Bratislava, Slovakia www.visitbratislava.com www.visitbratislava.com K a m z í k Hlavná stanica Railway Station 28 8 B WC 6 WC WC 26 9 B 24 Dear Tourism Friends, 23 5 13 25 27 We are pleased that you are reading velopment of tourism in Bratislava with as desired and provide services for 22 this publication that has been created an emphasis on improving the quality customer satisfaction. This publication to serve the professional community of life of the local population and in- offers more detailed information on 16 3 (tour operators, travel agents, agencies, creasing the satisfaction of visitors with the activity profile of BTB members, the AS Nivy Bus Station Nivy brokers, organizers of trips and events, their stay and services in the capital. portfolio of services they provide, and 4 B etc.) in getting to know Bratislava and The main tasks WCof BTB include network1 - includes useful contact information.20 We Gajova Chatam Hrad DeSofer 7 finding the right contacts for local travel ing and cooperation of partnersWC in the regularly update our members’ infor- vín professionals. The publication was cre- destination, creation and promotion of mation online:11 2 14 ated by Bratislava Tourist Board (BTB) tourism products, co-organization of www.visitbratislava.com/members. 17 and brought to you thanks to the sup- cultural and social events, promotion In addition to BTB members we have Nám. -

15. Bratislava Di Volo

Clean bus operation - experience in Tuscany, Netherlands and Slovakia SUMP- based development of bus transport solutions, the case of Bratislava – extension of the trolley bus network and fleet renewal JASPERS 26th - 27th June 2018 1 List of some projects co-financed by OPII (MoT) and IROP Both OPII & IROP support SUMPs (regions&cities) Projects co-financed by OPII: • The modernization of tram tracks in Košice • Tram purchase in Bratislava • Trolleybus fleet renewal in Prešov • Trolleybuses fleet renewal in Žilina • DPB, Modernization of the maintenance base - 2nd stage Projects co-financed by IROP: • Purchase of Electric buses in Bratislava • Informatization of public transport in Bratislava - Information Tables 2 SUMPs Clean transport, Urban transport • Sustainable Urban Mobility Planning is the most important topic in the Commission's Urban Mobility Package. • The Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan concept considers the functional urban area and foresees that plans are developed in cooperation across different policy areas and sectors, across different levels of government and administration and in cooperation with citizens and other stakeholders. Source: 19th June 2018 https://ec.europa.eu/transport/themes/urban/urban_mobility/urban_mobility_actions/sump_en Important: Transport Planning should always consider the three fundamental layers of a transport system – Organisation, Operation, Infrastructure – and be independent from funding / not constrained by administrative borders 3 SUMPs and Public Transport PSC 4 SK approach/methodology -

P R O G R a M M E

eTwinning Seminar Collaborative activities go beyond communication and exchange of materials Bratislava, Slovakia 10.-12. October 2019 VENUEVENUE Hotel Saffron Radlinského 27 811 07 Bratislava Slovak Republic http://www.hotelsaffron.sk/uvodna-stranka/language/en TARGET GROUPS eTwinning teachers (already registered), all subjects, cross-curricular Language: English Who: age of students: 7.-15 What: Join teachers from across Europe to network, share ideas and best practice. The key aim of the workshop is for participants to start a real COLLABORATIVE eTwinning project with other schools in Europe. Participating countries: Belgium fr, Belgium nl, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Moldova, Netherland, Romania, Portugal, Spain, UK, Slovakia. P R O G R A M M E Please note: Own laptops needed! October 10. Arrival of participants 15:00 – 15:30 Registration, Coffee / refreshment 15:30 – 18:45 Welcome speech: Lubica Sokolikova, Slovak NSS eTwinning overview – Gary Shiells, British Council /UK eTwinning/ Speed dating + networking Facilitator: Lubica Sokolikova, SK NSS 19:00 Dinner in the hotel October 11. Hands on workshops PARALEL WORKSHOPS A B 09:00 – 10:30 Art in projects Collaboration in project is Facilitator: Alexanda Gábor important Ambassador SK NSS Facilitator: Katarina Hvizdova Ambassador SK NSS 10:30 – 10:45 Coffee break 10:45 – 12:15 Collaboration in project is Art in projects important Facilitator: Alexandra Gábor Facilitator: Katarina Hvizdova Ambassador SK NSS Ambassador SK NSS 12:15 – 13:15 Lunch 13:15 – 14:45 Project Based Learning External tools in eTwinning Facilitator: Kornelia Lohynova, project Ambassador SK NSS Facilitator: Marcel Prievoznik Ambassador SK NSS 14:45 – 15:00 Coffee break 15:00 – 16:30 External tools in eTwinning Project Based Learning project Facilitator: Kornelia Lohynova, Facilitator: Marcel Prievoznik Ambassador SK NSS Ambassador SK NSS Free time – networking 19:00 – Dinner in the old town – Bratislavska restauracia, Bratislava flagship restaurant http://www.bratislavskarestauracia.sk/en/ October 12. -

Travel Behaviour of Seniors in Eastern Europe: a Comparative Study of Brno and Bratislava

European Transport Research Review (2018) 10: 16 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12544-018-0286-8 ORIGINAL PAPER Travel behaviour of seniors in Eastern Europe: a comparative study of Brno and Bratislava Michal Šimeček1 & Vít Gabrhel 1 & Marek Tögel1 & Michal Lazor1 Received: 5 August 2016 /Accepted: 18 January 2018 /Published online: 20 February 2018 # The Author(s) 2018. This article is an open access publication Abstract Purpose Although seniors represent a sizable group of a population with distinctive travelling needs, we lack knowledge about their travel behaviour related to usage of public transport in the context of Eastern Europe. This study aims to describe patterns of travel behaviour of senior citizens in two cities with similar size and key mobility characteristics – Brno (Czech Republic) and Bratislava (Slovakia). Methods The data was collected via travel behaviour survey. The final sample from Bratislava consisted of 1961 seniors of the age of 70 and older who accounted for 3343 trips. The final sample in Brno contained 63 seniors of the age of 70 years and older who conducted 151 trips. Results On average, inhabitants of Bratislava older than 70 years conducted 1.7 trips per day, whereas it was 1.5 trips per day in Brno. The seniors from Bratislava averagely spent 40 min on their trips per day and single trip usually took 24 min to them. In comparison, senior citizens from Brno mostly needed 28 min per single trip, albeit their daily travel took almost the same time (41 min). When it comes to mode choice, while seniors from Bratislava prefer walking the most (44%), their counterparts from Brno predominantly chose public transport (57%). -

REGIONAL ANALYSIS of CHALLENGES and NEEDS for Bratislava Region

REGIONAL ANALYSIS OF CHALLENGES AND NEEDS for Bratislava Region Version 1.4 D.T1.2.6 30 04 2020 Institute of Spatial Planning (IPP) CORCAP partner(s) Related catchment area (area of analysis) Related cross-border relations IPP Bratislavský kraj, Trnavský kraj, Nitriansky kraj CZ-SK, SK-AT, HU-SK Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. CURRENT SITUATION ANALYSIS ................................................................ 5 1.1. Geographical and socio-economic description of the area, delimitation and definition of its catchment area .......................................................................................................... 5 1.1.1. Identifying the corridor and determining its catchment area ................................................. 7 1.1.2. Connections with relevant TEN-T and RFC corridors in the area ............................................. 8 1.1.2.1. TEN-T corridors ................................................................................................... 8 1.1.2.2. Multimodal Transport Corridors ............................................................................... 9 1.1.2.3. AGC railways ...................................................................................................... 10 1.1.2.4. AGTC corridors ................................................................................................... 11 1.1.2.5. Railway freight corridors ...................................................................................... 13 1.1.2.6. Other corridors ................................................................................................. -

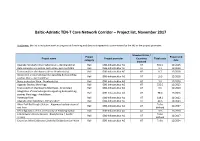

Baltic-Adriatic TEN-T Core Network Corridor – Project List, November 2017

Baltic-Adriatic TEN-T Core Network Corridor – Project list, November 2017 Disclaimer: this list is indicative work in progress still evolving and does not represent a commitment by the MS or the project promoter. Member States / Project Project end Project name Project promoter Countries Total costs category date involved Upgrade Nordbahn Wien Süßenbrunn - Bernhardsthal Rail ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG AT 592.0 12/2025 Data networks and mobile radio Wien -Bernhardsthal Rail ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG AT 2.1 12/2018 Train condition checkpoints Wien -Bernhardsthal Rail ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG AT 0.7 12/2018 Integration of interlockings into signalling & dispatching Rail ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG AT 10.5 12/2018 centres Wien - Bernhardsthal Noise protection Wien - Bernhardsthal Rail ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG AT 3.6 12/2020 Upgrade Stadlau-Marchegg Rail ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG AT 550.0 12/2023 Train condition checkpoints Marchegg - Arnoldstein Rail ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG AT 9.5 12/2020 Integration of interlockings into signalling & dispatching Rail ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG AT 98.6 12/2016 centres Marchegg - Arnoldstein Pottendorf line Rail ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG AT 618.2 12/2022 Upgrade Wien Meidling / Altmannsdorf Rail ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG AT 44.6 12/2023 Wien Zvbf Rail Freight Station - Alignment optimization of To be Rail ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG AT 12/2037 exit lines defined Reconfiguration of the accessibility of Himberg Station Rail ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG AT 10.5 12/2020 Link between Vienna Airport - Bruck/Leitha (- border To be Rail ÖBB-Infrastruktur AG AT 12/2017 AT/HU) defined -

Public Transport Growth for Bratislava

Public transport growth for Bratislava Ing. Tibor SCHLOSSER, CSc. – Peter BÁNOVEC City of Bratislava Viajeo Plus – city showcase Gothenburg, 12-14 May 2014 2 Viajeo Plus, Gothenburg, 12-14 May 2014 Bratislava metropolitan region Bratislavský samosprávny kraj 1,20 mio. inhabitants Trnavský samosprávny kraj Bratislava: 433 000 inhabitants Bratislava region: 629 000 inhabitants Trnava region (part): 563 000 inhabitants 3 Viajeo Plus, Gothenburg, 12-14 May 2014 Trolleys in Bratislava • 1909 first trolley track (Vydrická dolina – Železná studnička), closed 1915 • 1941 trolleys restored in city center, closed 1964 • 1941 another track to Patrónka (today big terminal) • 1943 third trolleybus line operating in Bratislava (castle – center – Koliba) • 1950 trolley line to ice stadium • 1955 network growth to Prievoz, closed 1965, restored 1986 • 1957 Ružová dolina connected • 1964 second trolley track closing • 1967 east network development (Trnávka) • 1971 third trolley track closing • 1984 trolleys are back (city centre – Rajská) • 1988 Prievoz track extended to Dolné Hony • 90´s network extension 2006 isolated circle in Karlova Ves – Dlhé diely 2012-14 new connections, large scale trolleybuses renew 4 Viajeo Plus, Gothenburg, 12-14 May 2014 Rail transport in Bratislava • 1840/1846 horse railway towards Trnava (to city edge and port) • 1848 steam track from Gänserndorf, 1850 to Budapest (bypass) • 1891 Danube railway bridge • 1895 tram network • 1914 tram across Danube: Wien – Bratislava, closed 1938 /1961 • 1952 - 83 new layout of railways – elimination from centre (bypases) • 1972/1984 operation to Nivy / Filiálka closed • 1972 plans for metro (1 station built) • 1997 metro conception change to VAL • 1998 new layout of Petržalka station • 2001 plan for metro and railway connection • 2004 plan for „Nosný systém“ – rail + tram • 2013 I.