Mental Health Act 2013: Review of the Act’S Operation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House of Assembly Tuesday 1 May 2018

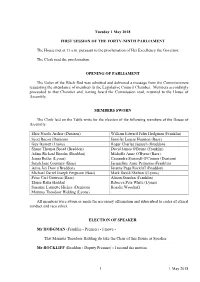

Tuesday 1 May 2018 FIRST SESSION OF THE FORTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT The House met at 11 a.m. pursuant to the proclamation of Her Excellency the Governor. The Clerk read the proclamation. OPENING OF PARLIAMENT The Usher of the Black Rod was admitted and delivered a message from the Commissioners requesting the attendance of members in the Legislative Council Chamber. Members accordingly proceeded to that Chamber and, having heard the Commission read, returned to the House of Assembly. MEMBERS SWORN The Clerk laid on the Table writs for the election of the following members of the House of Assembly. Elise Nicole Archer (Denison) William Edward Felix Hodgman (Franklin) Scott Bacon (Denison) Jennifer Louise Houston (Bass) Guy Barnett (Lyons) Roger Charles Jaensch (Braddon) Shane Thomas Broad (Braddon) David James O'Byrne (Franklin) Adam Richard Brooks (Braddon) Michelle Anne O'Byrne (Bass) Jenna Butler (Lyons) Cassandra Stanwell O'Connor (Denison) Sarah Jane Courtney (Bass) Jacqueline Anne Petrusma (Franklin) Anita Joy Dow ((Braddon) Jeremy Page Rockliff (Braddon) Michael Darrel Joseph Ferguson (Bass) Mark David Shelton ((Lyons) Peter Carl Gutwein (Bass) Alison Standen (Franklin) Eloise Rafia Haddad Rebecca Peta White (Lyons) Susanne Lynnette Hickey (Denison) Rosalie Woodruff Marinus Theodoor Hidding (Lyons) All members were sworn or made the necessary affirmation and subscribed to codes of ethical conduct and race ethics. ELECTION OF SPEAKER Mr HODGMAN (Franklin - Premier) - I move - That Marinus Theodoor Hidding do take the Chair of this House as Speaker. Mr ROCKLIFF (Braddon - Deputy Premier) - I second the motion. 1 1 May 2018 CLERK - Does the member consent to such nomination? Mr HIDDING (Lyons) - I do. -

DPAC Annual Report 2016-17

DPAC ANNUAL REPORT 2016 –17 Department of Premier and Cabinet Annual Report 2016–17 Department of Premier and Cabinet ABOUT THIS PUBLICATION This Annual Report provides information for all stakeholders with an interest in the machinery of government, policy services, whole-of-government service delivery, local government, information technology, State Service management, legislation development, security and emergency management, Aboriginal affairs, women’s policy, climate change, community development and sport and recreation. It includes the highlights of the year, an overview of our operations, major initiatives, and performance during 2016-17. The report is presented in several sections: Section Page Submission to the Premier and Ministers 1 Our Year in Review 2 Secretary’s Report 4 Our Department 6 Our Strategic Priorities – How we performed 11 Our Performance Measures 40 Our People and Policies 44 Our Divisions 55 Our Finances 60 Our Compliance Report 74 Compliance Index 84 Abbreviations 86 Index 88 Our Contacts Inside back cover All of our annual reports are available for download from the Department’s website, www.dpac.tas.gov.au. © Crown in the Right of the State of Tasmania For copies or further information regarding this Report please contact: Department of Premier and Cabinet GPO Box 123 Hobart TAS 7001 Call 03 6270 5482 Email [email protected] www.dpac.tas.gov.au ISSN 1448 9023 (print) ISSN 1448 9031 (online) Submission to the Premier and Ministers Hon Will Hodgman MP Hon Jeremy Rockliff MP Premier Minister for Education -

Premier of Tasmania - Anniversary of June 2016 Floods a Time for Reflection

Premier of Tasmania - Anniversary of June 2016 floods a time for reflection Search Home News About Cabinet Speeches Budget Contact Will Hodgman Premier of Tasmania 5 June 2017 Jeremy Rockliff, Minister for Primary Industries and Water Anniversary of June 2016 floods a time for reflection In marking the 12-month anniversary of last June’s devastating floods, it is a time to reflect on the tragic loss of life and the many families, farms and communities that were impacted. Once in a century floods swept across 20 of Tasmania’s 29 municipalities with enormous speed and causing catastrophic damage to farms and infrastructure and people’s livelihoods. It is difficult to adequately describe the heartache of missing family members, farmers losing stock or a family seeing their home go under water – it has a different impact on every individual. The community, including the Tasmanian Government, stood beside these families and communities as they rebuilt and we continue to help with rehabilitation grants, loans and financial advice. The total damage bill is estimated in excess of $180 million and my thanks go to the many organisations like the local councils, TFGA, Dairy Tas, Rural Business Tasmania, Rural Alive and Well, and DPIPWE who all worked magnificently together to help affected families and communities. The Tasmanian Government quickly responded with a series of Emergency Assistance Grants, Community and Primary Producer Clean-up Grants, funding to the Rural Relief Fund, established the Flood Recovery Taskforce, the Flood Recovery Loan Scheme and also successfully liaised with the Australian Government for the affected regions to be covered by the National Disaster Relief and Recovery Arrangement. -

Rti-Dl-Release-Dpipwe

From: O'Brien, Megan (DPaC) [mailto:Megan.O'[email protected]] Sent: Thursday, 22 December 2016 8:50 AM To: @tasracing. com. au>; Mark Tarring <rn. tarring@tasracing. com. au>; @tasracing. com. au> Cc: @tasracing. com. au>; @tasracing. com. au> Subject: Christmas break Good morning alt, A quick note to let you knowthat this office is closing at 12pm tomorrow. i will be on leave for the first week of January, returning Monday 9th January. Leanne will be your first contact while I'm away, however I'll still be available on my mobile. I want to wish the whole team at Tasracinga Merry Christmas and Happy NewYear! Enjoy the break, and thank you for all the fantastic work you've done throughout the year Warm regards, Megan RTI-DL-RELEASE-DPIPWE ^^w ^idau^ O'Brien, Me an (DPaC) From: Mark Tarring <rn.tarring@tasracing. com. au> Sent: Wednesday, 7 December2016 1127 AM To: O'Brien, Megan (DPaC) Cc: Casey Commane Subject: RE: GBE paper for checking Hi Megan, this is correct. I have spoken to Tascorp so give me a call and I can provide an update. Regards Mark Tarring | Tasracing Chief Financial Officer Luxbet Park Hobart 6 Goodwood Road Glenorchy TAS 7010 e: m. tarrin tasracin . corn. au w: www.tasracin .corn. au From: O'Brien, Megan (DPaC) [mailto:Megan. O'Brien@dpac. tas. gov. au] Sent: Wednesday, 7 December 2016 10:26 AM To: Mark Tarring <[email protected]> Cc: Casey Commane <[email protected]> Subject: GBE paper for checking Hi Mark, Can you please check the attached is correct, it has been through the Treasurer's office too - letters of comfort were in the Mercury today. -

Tasmania: Majority Or Minority Government? *

AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW Tasmania: Majority or Minority Government? * Michael Lester and Dain Bolwell PhD Candidate, Institute for the Study of Social Change, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Tasmania Associate, Institute for the Study of Social Change, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Tasmania * Double-blind reviewed article. INTRODUCTION While the outcome of the March 2018 Tasmanian State Election was predictable,1 the controversies that dogged the campaign were not. Yet it was the aftermath of the election that was most astonishing—not only to the public but also to members of Cabinet. Tasmania is different. Its parliamentary institutions are unusual and its electoral system is distinctive. So were the issues on which the March 2018 state election was fought. In the lead up to the election both major parties campaigned to govern alone or not at all—neither in minority nor in coalition with the Greens. As well as this apparently overarching concern, there were three other major issues prominent during the campaign—an acute housing shortage, the thousands of poker machines in pubs and clubs, and the surprise matter of gun control. Health, education, law and order, the economy and who would best manage the budget were, as usual, also policy battle grounds; however, the minority government fear campaign, a television blitz on the benefits of poker machines and considerable 1 N. Miragliotta, ‘As Tasmania Looks Likely to Have Minority Government, The Greens Must Decide How to Play Their Hand’, The Conversation, 26 February 2018. Accessed at: https://theconversation.com/as-tasmania-looks- likely-to-have-minority-government-the-greens-must-decide-how-to-play-their-hand-91985. -

Barton Deakin Standing Brief: Gutwein Ministry 24.01.2020 Following the Resignation of Will Hodgman MP As Premier of Tasmania

Barton Deakin Standing Brief: Gutwein Ministry 24.01.2020 Following the resignation of Will Hodgman MP as Premier of Tasmania, Peter Gutwein MP was appointed the 46th Premier on the 20th January. In addition to serving as Premier, Mr Gutwein will continue as Treasurer. Mr Gutwein will also serve as Minister for Climate Change, the first in a Tasmanian Liberal Government. Sarah Courtney MP will take on a new portfolio as Minister for Strategic Growth. Michael Ferguson MP will assist the Treasurer as Minister for Finance. Jane Howlett MLC will be promoted to the Ministry, serving as Minister for Sport, Recreation, and Racing. A number of serving ministers will take on additional portfolios: Elise Archer MP will take on Heritage; Sarah Courtney MP will take on Strategic Growth, Small Business, Hospitality and Events; Roger Jaensch MP will take on Environment and Parks; Jeremy Rockliff MP will take on Trade, Advanced Manufacturing and Defence Industries, Disability Services and Community Development. There are no changes to parliamentary secretaries. Title Minister Premier Treasurer Minister for Climate Change Peter Gutwein MP Minister for the Prevention of Family Violence Minister for Tourism Deputy Premier Minister for Education and Training Minister for Mental Health and Wellbeing Minister for Disability Services and Community Jeremy Rockliff MP Development Minister for Trade Minister for Advanced Manufacturing and Defence Industries Minister for Finance Minister for Infrastructure and Transport Minister for State Growth Michael Ferguson -

Government Services Budget Paper No 2

PARLIAMENT OF TASMANIA Government Services Budget Paper No 2 Volume 2 Presented by Hon Peter Gutwein MP, Treasurer, for the information of Honourable Members, on the occasion of the Budget, 2018-19 Useful 2018-19 Budget and Government Websites www.premier.tas.gov.au/budget_2018 Contains the 2018-19 Budget Paper documents and related information including Budget Fact Sheets and Government Media Releases. www.treasury.tas.gov.au Contains the 2018-19 Budget Papers and Budget Paper archives. www.tas.gov.au Provides links to the websites of Tasmanian public sector entities. www.service.tas.gov.au Provides a comprehensive entry point to Government services in Tasmania. CONTENTS VOLUME 1 PART 1: DEPARTMENTS 1 Introduction 2 Department of Communities Tasmania 3 Department of Education 4 Finance-General 5 Department of Health 6 Department of Justice 7 Ministerial and Parliamentary Support 8 Department of Police, Fire and Emergency Management 9 Department of Premier and Cabinet 10 Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment 11 Department of State Growth 12 Department of Treasury and Finance VOLUME 2 PART 2: AGENCIES 13 House of Assembly 14 Integrity Commission 15 Legislative Council 16 Legislature-General 17 Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions 18 Office of the Governor 19 Office of the Ombudsman 20 Tasmanian Audit Office 21 Tourism Tasmania i PART 3: STATUTORY AUTHORITIES 22 Inland Fisheries Service 23 Marine and Safety Tasmania 24 Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens 25 State Fire Commission 26 TasTAFE ii VOLUME 2: INDEX -

Tasmanian Ministry List 2021

Tasmanian Ministry List 2021 Minister Portfolio Hon. Peter Gutwein MP Premier Treasurer Minister for Tourism Minister for Climate Change Hon. Jeremy Rockliff MP Deputy Premier Minister for Health Minister for Mental Health and Wellbeing Minister for Community Services and Development Minister for Advanced Manufacturing and Defence Industries Hon. Sarah Courtney MP Minister for Education Minister for Skills, Training and Workforce Growth Minister for Disability Services Minister for Children and Youth Minister for Hospitality and Events Hon. Michael Ferguson MP Minister for State Development, Construction and Housing Minister for Infrastructure and Transport Minister for Finance Minister for Science and Technology Leader of the House Hon. Elise Archer MP Attorney General of Tasmania Minister for Justice Minister for Workplace Safety and Consumer Affairs Minister for Corrections Minister for the Arts Hon. Guy Barnett MP Minister for Trade Minister for Primary Industries and Water Minister for Energy and Emissions Reductions Minister for Resources Minister for Veterans’ Affairs Minister Portfolio Hon. Roger Jaensch MP Minister for State Growth Minister for the Environment Minister for Local Government and Planning Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Minister for Heritage Hon. Jane Howlett MLC Minister for Small Business Minister for Women Minister for Sport and Recreation Minister for Racing Hon. Jacquie Petrusma MP Minister for Police, Fire and Emergency Management Minister for the Prevention of Family Violence Minister for Parks Parliamentary Secretary Portfolio Madeleine Ogilvie MP Parliamentary Secretary to the Premier John Tucker MP Parliamentary Secretary to the Premier Government Whip Legislative Council Portfolio Hon. Leonie Hiscutt MLC Leader of the Government in the Legislative Council Hon. Jo Palmer MLC Deputy Leader of the Government in the Legislative Council . -

Proportional Representation in Theory and Practice the Australian Experience

Proportional Representation in Theory and Practice The Australian Experience Glynn Evans Department of Politics and International Relations School of Social Sciences The University of Adelaide June 2019 Table of Contents Abstract ii Statement of Authorship iii Acknowledgements iv Preface vi 1. Introduction 1 2. District Magnitude, Proportionality and the Number of 30 Parties 3. District Magnitude and Partisan Advantage in the 57 Senate 4. District Magnitude and Partisan Advantage in Western 102 Australia 5. District Magnitude and Partisan Advantage in South Eastern Jurisdictions 132 6. Proportional Representation and Minor Parties: Some 170 Deviating Cases 7. Does Proportional Representation Favour 204 Independents? 8. Proportional Representation and Women – How Much 231 Help? 9. Conclusion 247 Bibliography 251 Appendices 260 i Abstract While all houses of Australian parliaments using proportional representation use the Single Transferable Vote arrangement, district magnitudes (the numbers of members elected per division) and requirements for casting a formal vote vary considerably. Early chapters of this thesis analyse election results in search for distinct patterns of proportionality, the numbers of effective parties and partisan advantage under different conditions. This thesis argues that while district magnitude remains the decisive factor in determining proportionality (the higher the magnitude, the more proportional the system), ballot paper numbering requirements play a more important role in determining the number of (especially) parliamentary parties. The general pattern is that, somewhat paradoxically, the more freedom voters have to choose their own preference allocations, or lack of them, the smaller the number of parliamentary parties. Even numbered magnitudes in general, and six member divisions in particular, provide some advantage to the Liberal and National Parties, while the Greens are disadvantaged in five member divisions as compared to six or seven member divisions. -

SEPTEMBER 2019 Our School Plan Backed the Brighton Community Rior Rural Site on the Out- Has Given Strong Support Skirts of Brighton

Community News VOL 21 NO 8 SEPTEMBER 2019 www.brightoncommunitynews.com.au Our school plan backed THE Brighton community rior rural site on the out- has given strong support skirts of Brighton. for the development of the While claiming the Edu- new $30-million Brighton cation Department’s consul- High School on the site of tation was “blue sky”, with the School Farm in the all site options on the table, centre of Brighton. by then announcing just Independent polling and three site options it was the community response to apparent that the State Gov- the Education Department’s ernment and officials had consultation on the location already removed the School of the high school point to Farm site from considera- a strong preference for it to tion. be built on the current site This was strongly criti- of the Jordan River Learning cised by attendees at the Federation’s School Farm in meeting and the Education the centre of Brighton. Department officials had The extensive poll, cov- difficulty in defending the ering the Brighton munici- decision, other than to say pality and conducted by the government had com- respected independent poll- mitted to improving the sters Myriad Research dur- School Farm on the current ing August, showed almost site. 60 percent of respondents in The three sites under favour of the high school government consideration being developed on the are the Pontville Park sports School Farm site and the grounds, the Racecourse farm being moved to Road/Seymour Street recre- About 100 residents and community members, including Minister for Education Jeremy Rockliff, Opposition Leader Rebecca White, Mayor Tony Foster Brighton’s outskirts. -

Legislative Council Estimates B

PARLIAMENT OF TASMANIA TRANSCRIPT LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ESTIMATES COMMITTEE B Hon. Jeremy Rockliff MP Thursday 26 November 2020 MEMBERS Hon Rosemary Armitage MLC Hon Ivan Dean MLC Hon Jo Palmer MLC Hon Tania Rattray MLC (Chair) Hon Jo Siejka MLC Hon Josh Willie MLC WITNESSES IN ATTENDANCE Hon. Jeremy Rockliff MP, Deputy Premier; Minister for Education and Training; Minister for Mental Health and Wellbeing; Minister for Disability Services and Community Development; Minister for Trade; Minister for Advanced Manufacturing and Defence Industries Mr Tim Bullard, Secretary, Department of Education Ms Trudy Pearce, Deputy Secretary – Learning, Department of Education Ms Jenny Burgess, Deputy Secretary – Strategy and Performance, Department of Education Ms Katharine O’Donnell, Registrar Education Mr Kane Salter, Director -Finance and Budget Services, Department of Education Mr Bob Rutherford, Deputy Secretary Industry and Business Development, Department of State Growth Ms Angela Conway, General Manager, Workforce Development and Training, Skills Tasmania Ms Liz Jack, Executive Director Libraries Tasmania Ms Jenny Dodd, Chief Executive Officer, TasTAFE Mr Scott Adams, Chief Financial Officer, TasTAFE Mr Craig Jeffery, Chief Financial Officer, Department of Health Ms Kathrine Morgan-Wicks, Secretary, Department of Health Mr Dale Webster, Deputy Secretary, Community, Mental Health and Wellbeing, Department of Health Ms Ingrid Ganley, Director, Disability and Community Services, Department of Communities Tasmania Mr Michael Pervan, Secretary, Department -

Community Directory

Community Directory Central Coast at a glance Our history Our icons Emergency services Message from the Mayor Community Directory Central Coast is situated in North-West Tasmania and comprises an area of 932sq.km. Central Coast 1 The area lies at a latitude of 41.30 S and a longitude of 146 E. at a glance Central Coast spans from the Blythe River east to the settlement of Leith at Braddons Our history Lookout Road, and extends back from the coastline of Bass Strait to the Black Bluff range in the south. Of the 29 municipal areas in Tasmania, Central Coast is the seventh largest Our icons in population. Emergency services The coastal town of Ulverstone is the urban centre, with the second largest town of Penguin located 13km to its west. Message from the Mayor The longest river in Central Coast is the Leven River (90km). The highest mountain is Black Bluff (1339m). Community Directory The area enjoys a maritime temperate climate, with mean maximum to minimum temperatures* in mid-summer of 21C to 12C and in mid-winter of 12C to 4C. The 2018 Estimated Resident Population** for the Central Coast municiapl area is 21,904, with a population density of 0.23 persons per hectare. The 2018 population for: • Penguin - Sulphur Creek - Heybridge – 5,194, with a population density of 0.81 persons/ha [encompasses Heybridge (part), Howth, Penguin, Preservation Bay and Sulphur Creek] • West Ulverstone – 4,243, with a population density of 2.38 persons/ha • Ulverstone - Gawler – 7,252, with a population density of 1.31 persons/ha • Turners Beach -