Guinness Atkinson Datong Case Study August 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

The Second Circular

The 24th World Congress of Philosophy Title: The XXIV World Congress of Philosophy (WCP2018) Date: August 13 (Monday) - August 20 (Monday) 2018 Venue: Peking University, Beijing, P. R. China Official Language: English, French, German, Spanish, Russian, Chinese Congress Website: wcp2018.pku.edu.cn Program: Plenary Sessions, Symposia, Endowed Lectures, 99 Sections for Contributed Papers, Round Tables, Invited Sessions, Society Sessions, Student Sessions and Poster Sessions Organizers: International Federation of Philosophical Societies Peking University CONFUCIUS Host: Chinese Organizing Committee of WCP 2018 Important Dates Paper Submission Deadline February 1, 2018 Proposal Submission Deadline February 1, 2018 Early Registration October 1, 2017 On-line Registration Closing June 30, 2018 On-line Hotel Reservation Closing August 6, 2018 Tour Reservation Closing June 30, 2018 * Papers and proposals may be accepted after that date at the discretion of the organizing committee. LAO TZE The 24th World Congress of Philosophy MENCIUS CHUANG TZE CONTENTS 04 Invitation 10 Organization 17 Program at a Glance 18 Program of the Congress 28 Official Opening Ceremony 28 Social and Cultural Events 28 Call for Papers 30 Call for Proposals WANG BI HUI-NENG 31 Registration 32 Way of Payment 32 Transportation 33 Accommodation 34 Tours Proposals 39 General Information CHU HSI WANG YANG-MING 02 03 The 24th World Congress of Philosophy Invitation WELCOME FROM THE PRESIDENT OF FISP Chinese philosophy represents a long, continuous tradition that has absorbed many elements from other cultures, including India. China has been in contact with the scientific traditions of Europe at least since the time of the Jesuit Matteo Ricci (1552-1610), who resided at the Imperial court in Beijing. -

The Effect of Meteorological Variables on the Transmission of Hand, Foot

RESEARCH ARTICLE The Effect of Meteorological Variables on the Transmission of Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease in Four Major Cities of Shanxi Province, China: A Time Series Data Analysis (2009-2013) Junni Wei1*, Alana Hansen2, Qiyong Liu3,4, Yehuan Sun5, Phil Weinstein6, Peng Bi2* 1 Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, Shanxi, China, 2 Discipline of Public Health, School of Population Health, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, 3 State Key Laboratory for Infectious Diseases Prevention and Control, National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, China, 4 Shandong University Climate Change and Health Center, Jinan, Shandong, China, 5 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, Anhui, China, 6 Division of Health Sciences, School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, The University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia OPEN ACCESS * [email protected] (JW); [email protected] (PB) Citation: Wei J, Hansen A, Liu Q, Sun Y, Weinstein P, Bi P (2015) The Effect of Meteorological Variables on the Transmission of Hand, Foot and Mouth Abstract Disease in Four Major Cities of Shanxi Province, China: A Time Series Data Analysis (2009-2013). Increased incidence of hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) has been recognized as a PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9(3): e0003572. doi:10.1371/ journal.pntd.0003572 critical challenge to communicable disease control and public health response. This study aimed to quantify the association between climate variation and notified cases of HFMD in Editor: Rebekah Crockett Kading, Genesis Laboratories, UNITED STATES selected cities of Shanxi Province, and to provide evidence for disease control and preven- tion. -

The Ballad of Mulan Report and Poem

Wolfe !1 Brady Wolfe Dr. Christensen CHIN 343 December 8, 2015 Mulan China to me for many years was defined by the classic story of Mulan. It was a foreign land as far away from me as anything I could fathom, yet it was so fascinating to me that I would of- ten even pretend I could speak Chinese, and I still remember the excitement I felt when as a young child I first watched Disney’s retelling of Mulan. I watched it over and over again, and when I went to China for the first time, I was honestly quite surprised to find that today’s China was quite different from my childhood imaginations inspired by that movie. For this reason, when I discovered that the legend of Mulan originates from an ancient Chinese poem, I decided it would be appropriate and enjoyable for me to choose this poem as the subject of my translation and research project. The core of this project is my own translation of the classic poem, and addi- tionally I will discuss a little bit about the history of the poem, and analyze its structure and for- mat. The original source for the poem of Mulan has been lost, but it was transcribed into the Music Bureau Collections, an anthology by Guo Maoqing put together sometime during the Song dy- nasty around the 11th or 12th century A.D., and a note is given by Guo saying that the source from which it was taken and transcribed into the collection was a compilation made during the beginning of the Tang dynasty, more or less 6th century A.D., called the Musical Records of Old and New, (Project Gutenberg). -

Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis

arts Article Cultural “Authenticity” as a Conflict-Ridden Hypotext: Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis Zhuoyi Wang Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, Hamilton College, Clinton, NY 13323, USA; [email protected] Received: 6 June 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 10 July 2020 Abstract: Disney’s Mulan (1998) has generated much scholarly interest in comparing the film with its hypotext: the Chinese legend of Mulan. While this comparison has produced meaningful criticism of the Orientalism inherent in Disney’s cultural appropriation, it often ironically perpetuates the Orientalist paradigm by reducing the legend into a unified, static entity of the “authentic” Chinese “original”. This paper argues that the Chinese hypotext is an accumulation of dramatically conflicting representations of Mulan with no clear point of origin. It analyzes the Republican-era film adaptation Mulan Joins the Army (1939) as a cultural palimpsest revealing attributes associated with different stages of the legendary figure’s millennium-long intertextual metamorphosis, including a possibly nomadic woman warrior outside China proper, a Confucian role model of loyalty and filial piety, a Sinitic deity in the Sino-Barbarian dichotomy, a focus of male sexual fantasy, a Neo-Confucian exemplar of chastity, and modern models for women established for antagonistic political agendas. Similar to the previous layers of adaptation constituting the hypotext, Disney’s Mulan is simply another hypertext continuing Mulan’s metamorphosis, and it by no means contains the most dramatic intertextual change. Productive criticism of Orientalist cultural appropriations, therefore, should move beyond the dichotomy of the static East versus the change-making West, taking full account of the immense hybridity and fluidity pulsing beneath the fallacy of a monolithic cultural “authenticity”. -

Silk Road Fashion, China. the City and a Gate, the Pass and a Road – Four Components That Make Luoyang the Capital of the Silk Roads Between 1St and 7Th Century AD

https://publications.dainst.org iDAI.publications ELEKTRONISCHE PUBLIKATIONEN DES DEUTSCHEN ARCHÄOLOGISCHEN INSTITUTS Dies ist ein digitaler Sonderdruck des Beitrags / This is a digital offprint of the article Patrick Wertmann Silk Road Fashion, China. The City and a Gate, the Pass and a Road – Four components that make Luoyang the capital of the Silk Roads between 1st and 7th century AD. The year 2018 aus / from e-Forschungsberichte Ausgabe / Issue Seite / Page 19–37 https://publications.dainst.org/journals/efb/2178/6591 • urn:nbn:de:0048-dai-edai-f.2019-0-2178 Verantwortliche Redaktion / Publishing editor Redaktion e-Jahresberichte und e-Forschungsberichte | Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Weitere Informationen unter / For further information see https://publications.dainst.org/journals/efb ISSN der Online-Ausgabe / ISSN of the online edition ISSN der gedruckten Ausgabe / ISSN of the printed edition Redaktion und Satz / Annika Busching ([email protected]) Gestalterisches Konzept: Hawemann & Mosch Länderkarten: © 2017 www.mapbox.com ©2019 Deutsches Archäologisches Institut Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Zentrale, Podbielskiallee 69–71, 14195 Berlin, Tel: +49 30 187711-0 Email: [email protected] / Web: dainst.org Nutzungsbedingungen: Die e-Forschungsberichte 2019-0 des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts stehen unter der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Namensnennung – Nicht kommerziell – Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 International. Um eine Kopie dieser Lizenz zu sehen, besuchen Sie bitte http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ -

CHINA BRIEFING the Practical Application of China Business

CHINA BRIEFING The Practical Application of China Business Business Guide to Central China HEILONGJIANG Harbin Urumqi JILIN Changchun XINJIANG UYGHUR A. R. Shenyang LIAONING INNER MONGOLIABEIJING A. R. GANSU Hohhot HEBEI TIANJIN Shijiazhuang Yinchuan NINGXIA Taiyuan HUI A. R. Jinan Xining SHANXI SHAN- QINGHAI Lanzhou DONG Xi'an Zhengzhou JIANG- SHAANXI HENAN SU TIBET A.R. Hefei Nan- jing SHANGHAI Lhasa ANHUI SICHUAN HUBEI Chengdu Wuhan Hangzhou CHONGQING ZHE- Nanchang JIANG Changsha HUNAN JIANGXIJIANGXI GUIZHOU Fuzhou Guiyang FUJIAN Kunming Taiwan YUNNAN GUANGXI GUANGDONG ZHUANG A. R. Guangzhou Nanning HONG KONG MACAU HAINAN Haikou Featuring the Central Chinese Provinces and Autonomous Regions of Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Inner Mongolia, Jiangxi and Shanxi Including the Mainland Cities of Baotou, Changde, Changsha, Datong, Hohhot, Kaifeng, Luoyang, Manzhouli, Nanchang, Taiyuan, Wuhan, Yichang and Zhengzhou Produced in association with Dezan Shira & Associates Business Guide to Central China Published by: Asia Briefing Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in retrieval systems or transmitted in any forms or means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher. Although our editors, analysts, researchers and other contributors try to make the information as accurate as possible, we accept no responsibility for any financial loss or inconvenience sustained by anyone using this guidebook. The information contained herein, including any expression of opinion, analysis, charting or tables, and statistics has been obtained from or is based upon sources believed to be reliable but is not guaranteed as to accuracy or completeness. © 2008 Asia Briefing Ltd. Suite 904, 9/F, Wharf T&T Centre, Harbour City 7 Canton Road, Tsimshatsui Kowloon HONG KONG ISBN 978-988-17560-4-6 China Briefing online: www.china-briefing.com "China Briefing" and logo are registered trademarks of Asia Briefing Ltd. -

The Real Story of Mulan By: the Scribe on Friday, June 17, 2011

The Real Story of Mulan By: The Scribe on Friday, June 17, 2011 Many people have seen the Disney movie Mulan and do not realize that it is actually telling the story of an ancient Chinese poem titled the Ballad of Mulan. Because it is a legend, it is unknown when Mulan may have lived although she was believed to have lived during theNorthern Wei dynasty which lasted from 386CE to 534CE. In the movie, Mulan is depicted as being unskilled with weapons. The “real” Mulan, on the other hand, was said to have practiced with many different weapons. The area in which she was believed to have lived was known for practicing martial arts such as Kung Fu and for being skilled with the sword. In the legend, the real Mulan (whose name was actually Hua Mulan) rode horses and shooting arrows. In the movie as well as in the poem, there was no male child. This caused problems when the Emperor (or Khan as he is called in the poem) began to call up troops to fight the invading Mongol and nomadic tribes. If there had been a son he could have gone in his father’s place as it was only up to the family to provide one man to fight. Whether it was the father or the son did not matter; all they needed to do was provide one person to join the army. As in the Disney movie, Mulan chose to enlist in her father’s place as he was too old to fight. At the age of eighteen she joined the army and prepared to fight against the Mongolian and nomadic tribes that wanted to invade China. -

Copyrighted Material

INDEX Aodayixike Qingzhensi Baisha, 683–684 Abacus Museum (Linhai), (Ordaisnki Mosque; Baishui Tai (White Water 507 Kashgar), 334 Terraces), 692–693 Abakh Hoja Mosque (Xiang- Aolinpike Gongyuan (Olym- Baita (Chowan), 775 fei Mu; Kashgar), 333 pic Park; Beijing), 133–134 Bai Ta (White Dagoba) Abercrombie & Kent, 70 Apricot Altar (Xing Tan; Beijing, 134 Academic Travel Abroad, 67 Qufu), 380 Yangzhou, 414 Access America, 51 Aqua Spirit (Hong Kong), 601 Baiyang Gou (White Poplar Accommodations, 75–77 Arch Angel Antiques (Hong Gully), 325 best, 10–11 Kong), 596 Baiyun Guan (White Cloud Acrobatics Architecture, 27–29 Temple; Beijing), 132 Beijing, 144–145 Area and country codes, 806 Bama, 10, 632–638 Guilin, 622 The arts, 25–27 Bama Chang Shou Bo Wu Shanghai, 478 ATMs (automated teller Guan (Longevity Museum), Adventure and Wellness machines), 60, 74 634 Trips, 68 Bamboo Museum and Adventure Center, 70 Gardens (Anji), 491 AIDS, 63 ack Lakes, The (Shicha Hai; Bamboo Temple (Qiongzhu Air pollution, 31 B Beijing), 91 Si; Kunming), 658 Air travel, 51–54 accommodations, 106–108 Bangchui Dao (Dalian), 190 Aitiga’er Qingzhen Si (Idkah bars, 147 Banpo Bowuguan (Banpo Mosque; Kashgar), 333 restaurants, 117–120 Neolithic Village; Xi’an), Ali (Shiquan He), 331 walking tour, 137–140 279 Alien Travel Permit (ATP), 780 Ba Da Guan (Eight Passes; Baoding Shan (Dazu), 727, Altitude sickness, 63, 761 Qingdao), 389 728 Amchog (A’muquhu), 297 Bagua Ting (Pavilion of the Baofeng Hu (Baofeng Lake), American Express, emergency Eight Trigrams; Chengdu), 754 check -

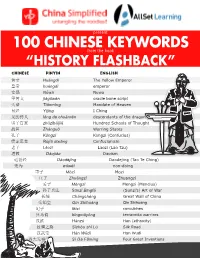

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

The Politics of Place-Making in the Records of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang

_full_journalsubtitle: International Journal of Chinese Studies/Revue Internationale de Sinologie _full_abbrevjournaltitle: TPAO _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 0082-5433 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 1568-5322 (online version) _full_issue: 1-2 _full_issuetitle: 0 _full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien J2 voor dit article en vul alleen 0 in hierna): Manling Luo _full_alt_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, hier invullen): The Politics of Place-Making _full_is_advance_article: 0 _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 T’OUNG PAO The Politics of Place-Making T’oung Pao 105 (2019) 43-75 www.brill.com/tpao 43 The Politics of Place-Making in the Records of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang Manling Luo Indiana University The Luoyang qielan ji 洛陽伽藍記 (Records of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang; hereafter Records), compiled by Yang Xuanzhi 楊衒之 (fl. 547) in roughly 547 CE, commemorates the ruined capital city of the North- ern Wei dynasty 北魏 (386-534).1 One of the few major works to survive from the period, the Records has received much critical attention, with topics ranging from its textual history to its historical and literary value. This essay focuses on what I call the “politics of place-making” in the memoir, that is, engagements with Luoyang’s space as expressions of power before and after the city’s abandonment, as represented and un- derstood by Yang. These ignored aspects shed light on the central con- cerns that motivated his writing, thereby revealing his perspective on the intersections of place, power, and human agency. The analysis al- lows us to better understand his innovations in pioneering an unofficial, space-centered historiography that defines historical agents as place- makers whose deeds and lives are anchored spatially as much as tempo- rally. -

Transport Corridors and Regional Balance in China: the Case of Coal Trade and Logistics Chengjin Wang, César Ducruet

Transport corridors and regional balance in China: the case of coal trade and logistics Chengjin Wang, César Ducruet To cite this version: Chengjin Wang, César Ducruet. Transport corridors and regional balance in China: the case of coal trade and logistics. Journal of Transport Geography, Elsevier, 2014, 40, pp.3-16. halshs-01069149 HAL Id: halshs-01069149 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01069149 Submitted on 28 Sep 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Transport corridors and regional balance in China: the case of coal trade and logistics Dr. Chengjin WANG Key Laboratory of Regional Sustainable Development Modeling Institute of Geographical Sciences and Natural Resources Research Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China Email: [email protected] Dr. César DUCRUET1 National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) UMR 8504 Géographie-cités F-75006 Paris, France Email: [email protected] Pre-final version of the paper published in Journal of Transport Geography, special issue on “The Changing Landscapes of Transport and Logistics in China”, Vol. 40, pp. 3-16. Abstract Coal plays a vital role in the socio-economic development of China. Yet, the spatial mismatch between production centers (inland Northwest) and consumption centers (coastal region) within China fostered the emergence of dedicated coal transport corridors with limited alternatives.