Industry, Economy and Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PG Restructured Syllabus with Effect from June 2016

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY M.A SYLLABUS Cat. Sub.Codes Sub.Title MC 16PSO1MC01 PRINCIPLES OF SOCIOLOGY MC 16PSO1MC02 SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY MC 16PSO1MC03 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY INDIAN SOCIETY: MC 16PSO1MC04 STRUCTURE AND PROCESS ENVIRONMENTAL MC 16PSO1MC05 SOCIOLOGY CONTEMPORARY MC 16PSO2MC01 SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY SOCIOLOGY OF MC 16PSO2MC02 DEVELOPMENT MC 16PSO2MC03 SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY MC 16PSO2MC04 INDUSTRIAL SOCIOLOGY ES 16PSO2ES01 SOCIAL MOVEMENTS ES 16PSO2ES02 HUMAN RIGHTS FC 16PHE2FC01 LIFE SKILLS TRAINING MC 16PSO3MC01 SOCIOLOGY OF HEALTH SOCIOLOGY OF MC 16PSO3MC02 ORGANIZATION HUMAN RESOURCES MC 16PSO3MC03 MANAGEMENT MC 16PSO3MC04 INDIAN SOCIAL PROBLEMS ID 16PSO3ID01 MEDIA AND SOCIETY ~ 1 ~ ES 16PSO3ES01 RURAL SOCIOLOGY ES 16PSO3ES02 URBAN SOCIOLOGY SUMMER TRAINING TP 16PSO3TP01 PROGRAMME NGO AND DEVELOPMENT MC 16PSO4MC01 PRACTICE GUIDANCE AND MC 16PSO4MC02 COUNSELLING QUALITATIVE AND MC 16PSO4MC03 QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS MC 16PSO4MC05 PROJECT ~ 2 ~ 16PSO1MC01 PRINCIPLES OF SOCIOLOGY SEMESTER I CREDITS 6 CATEGORY MC(T) NO.OF HOURS/ WEEK 6 Unit-I: Origin and Development of Sociology: Meaning, Nature and Scope of Sociology, Sociology as a Science- Relationship with other Social Sciences. Individual and Society, Heredity and environment, Co-operation. Unit-II: Socialization: Stages and Agencies of Socialization. Social and cultural Processes: Co- operation, Accommodation, Assimilation, Competition and conflict. Social Groups: Meaning, Types of Groups- Primary, Secondary, In- Group, Out-Group and Reference Group. Social Control: Factors and Agencies of Social Control. Unit-III: Social Institutions:Marriage- Monogamy, Polygamy, Polygyny, Polyandry, Hypergamy, Hypogamy, Endogamy, Exogamy, Levirate, Sorrorate. Rules and Residense: Patrilocal, Matrilocal, Avanculocal, Neo-local, Divorce. Family: Joint Family, Nuclear Family, Extended Family. Economy: Production Relation- Division of Labour- Concept of Class Distribution. Polity: Government – State and Nation- Power, Electoral System, Voting. -

Centennial Bibliography on the History of American Sociology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 2005 Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology Michael R. Hill [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Hill, Michael R., "Centennial Bibliography On The iH story Of American Sociology" (2005). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 348. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/348 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Hill, Michael R., (Compiler). 2005. Centennial Bibliography of the History of American Sociology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association. CENTENNIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE HISTORY OF AMERICAN SOCIOLOGY Compiled by MICHAEL R. HILL Editor, Sociological Origins In consultation with the Centennial Bibliography Committee of the American Sociological Association Section on the History of Sociology: Brian P. Conway, Michael R. Hill (co-chair), Susan Hoecker-Drysdale (ex-officio), Jack Nusan Porter (co-chair), Pamela A. Roby, Kathleen Slobin, and Roberta Spalter-Roth. © 2005 American Sociological Association Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS Note: Each part is separately paginated, with the number of pages in each part as indicated below in square brackets. The total page count for the entire file is 224 pages. To navigate within the document, please use navigation arrows and the Bookmark feature provided by Adobe Acrobat Reader.® Users may search this document by utilizing the “Find” command (typically located under the “Edit” tab on the Adobe Acrobat toolbar). -

Introduction to Sociology – SOC101 VU Introduction to Sociology SOC101 Table of Contents Page No

Introduction to Sociology – SOC101 VU Introduction to Sociology SOC101 Table of Contents Page no. Lesson 1 The Origins of Sociology………………………………………. 1 Lesson 2 Sociological Perspective……………………………. 4 Lesson 3 Theoretical Paradigms………………………………………….. 7 Lesson 4 Sociology as Science……………………………………………. 10 Lesson 5 Steps in Sociological Investigation……………………………… 12 Lesson 6 Social Interaction………………………………………………. 14 Lesson 7 Social Groups………………………………………………….. 17 Lesson 8 Formal Organizations……………………………………… 20 Lesson 9 Culture………………………………………………………….. 23 Lesson 10 Culture (continued)…………………………………………….. 25 Lesson 11 Culture (continued)………………………………........................ 27 Lesson 12 Socialization: Human Development……………………………. 30 Lesson 13 Understanding the Socialization Process……………………… 33 Lesson 14 Agents of Socialization…………………………………............ 36 Lesson 15 Socialization and the Life Course …………………………….. 38 Lesson 16 Social Control and Deviance ………………………………… 41 Lesson 17 The Social Foundations of Deviance…………………………. 43 Lesson 18 Explanations of Crime………………………………………… 45 Lesson 19 Explanations of Crime (continued)…………………………….. 47 Lesson 20 Social Distribution of Crime: Explanations…………………….. 51 Lesson 21 Social Stratification: Introduction and Significance……………... 55 Lesson 22 Theories of Class and Stratification-I…………………………… 57 Lesson 23 Theories of Class and Stratification-II…………………………. 59 Lesson 24 Theories of Class and Stratification-III…………………….. 61 Lesson 25 Social Class As Subculture……………………………………… 62 Lesson 26 Social Mobility………………………………… -

Sociology, Work and Industry/Tony J

Sociology,Work and Industry This popular text explains and justifies the use of sociological imagi- nation to understand the nature of institutions of work, occupations, organisations, management and employment and how they are changing in the twenty-first century. With outstanding breadth of coverage it provides an authoritative overview of both traditional and emergent themes in the sociological study of work; explains the basic logic of sociological analysis of work and work-related institutions; and provides an appreciation of different theoretical traditions. It fully considers: • the direction and implications of trends in technological change, globalisation, labour markets, work organisation, managerial practices and employment relations; • the extent to which these trends are intimately related to changing patterns of inequality in modern societies and to the changing experiences of individuals and families; • the ways in which workers challenge, resist and make their own contributions to the patterning of work and shaping of work institutions. New features include an easy-to-read, fully signposted layout, key issue questions, snapshot case studies, chapter summaries and a companion website which contains useful resources (for students and teachers). All of these elements – and much more – provide you with a text unrivalled in the field. Tony J. Watson is Professor of Organisational Behaviour in the Nottingham University Business School, University of Nottingham. Sociology,Work and Industry Fifth edition Tony J.Watson First edition published 1980 Second edition published 1987 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd Reprinted 1988, 1991, 1993 and 1995 Third edition 1995 Fourth edition published 2003 by Routledge Reprinted 2004, 2005, 2006 Fifth edition 2008 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2008. -

American Sociological Review

American Sociological Review http://asr.sagepub.com/ Precarious Work, Insecure Workers: Employment Relations in Transition Arne L. Kalleberg American Sociological Review 2009 74: 1 DOI: 10.1177/000312240907400101 The online version of this article can be found at: http://asr.sagepub.com/content/74/1/1 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: American Sociological Association Additional services and information for American Sociological Review can be found at: Email Alerts: http://asr.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://asr.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://asr.sagepub.com/content/74/1/1.refs.html Downloaded from asr.sagepub.com at INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFC on October 28, 2010 2008 PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS Precarious Work, Insecure Workers: Employment Relations in Transition Arne L. Kalleberg University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill The growth of precarious work since the 1970s has emerged as a core contemporary concern within politics, in the media, and among researchers. Uncertain and unpredictable work contrasts with the relative security that characterized the three decades following World War II. Precarious work constitutes a global challenge that has a wide range of consequences cutting across many areas of concern to sociologists. Hence, it is increasingly important to understand the new workplace arrangements that generate precarious work and worker insecurity. A focus on employment relations forms the foundation of theories of the institutions and structures that generate precarious work and the cultural and individual factors that influence people’s responses to uncertainty. Sociologists are well-positioned to explain, offer insight, and provide input into public policy about such changes and the state of contemporary employment relations. -

Alvin W. Gouldner and Industrial Sociology at Columbia University

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Sociology & Criminology Faculty Publications Sociology & Criminology Department 2001 Alvin W. Gouldner and Industrial Sociology at Columbia University James Chriss Cleveland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clsoc_crim_facpub Part of the Criminology Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Publisher's Statement The definitive version is available at www3.interscience.wiley.com Repository Citation Chriss, James, "Alvin W. Gouldner and Industrial Sociology at Columbia University" (2001). Sociology & Criminology Faculty Publications. 24. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clsoc_crim_facpub/24 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology & Criminology Department at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology & Criminology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALVIN W. GOULDNER AND INDUSTRIAL SOCIOLOGY AT COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY James J. Chriss, Cleveland State University Alvin W Gouldner (1920-1980) was a prolific socicl.ogist of the post-World War II era who spent the early part of his career (the 1950,) in the field of industrial , ociology. A case study of Gouldner's early life and career is useful insofar as it intertwines with the develcyment of industrial sociology as a distinct subfield within sociology. Through this analysis we are also better able to understand how and in what ways a burgeoning orga nizational studi es program develcyed at Ccl.umbia University during the 1940,. This anal ysis of the historical and cultural contexts within which Gouldner came to prcminence as an industrial sociologist at Columbia, and the intellectual program that resulted, can al so help shed light on more r ecent trends in organizational studies. -

The Turn to Public Sociology: the Case of U.S. Labor Studies

THE TURN TO PUBLIC SOCIOLOGY: THE CASE OF U.S. LABOR STUDIES. 1 Michael Burawoy N the US, 1974 marked the beginning of a great transformation. In labor studies it was I the year of the publication of Harry Braverman’s Labor and Monopoly Capital , and the launching of a Marxist research program focused on the labor process. Braverman turned away from all subjectivist views of work to proclaim his famous deskilling hypothesis, namely the history of monopoly capitalism was the history of the degradation of work. True or false, it was a decisive break with narrowly conceived industrial sociology and timeless organization theory. 1974 also marked a major recession in the US economy and the onset of an economic and then a political assault on labor that would throw Braverman’s claims into relief. More broadly, this birth of neoliberalism, capitalism’s third wave of marketization, would deeply affect both the labor movement and the focus of academic research. It is the changing relationship among economic and political context, labor movement and labor studies that preoccupies this paper. The rupture with professional sociology marked by Labor and Monopoly Capital , and the research program it inaugurated, was followed by a transition , some 20 years later, from the study of the labor process to an engagement with the labor movement. This transition to public sociology has been one of the more exciting developments in an otherwise heavily professionalized discipline and a generally bleak labor scene. Yet the shift of focus from structure to agency, from process to movement, from a critical- professional sociology to a critical-public sociology of labor occurred in the very period of the labor movement’s greatest decline -- the percentage of the labor force unionized in the private sector fell precipitously from 23.6% in 1974 to 7.4% by 2006. -

Industrial Socialisation and Role Performance in Contemporary Organization

International Journal of Business, Humanities and Technology Vol. 2 No. 5; August 2012 Industrial Socialisation and Role Performance in Contemporary Organization Bassey, Antigha Okon, Phd Lecturer Department of Sociology University of Calabar P.M.B. 1115 Calabar, C.R.S. Nigeria Attah, Frank, PhD Lecturer Department of Sociology University of Calabar P.M.B. 1115 Calabar, C.R.S. Nigeria Bassey, Umo Antigha, B.ED., CPA Unified Local Government Service Commission Cross River State Abstract This article is an analysis of the concept, Industrial Socialization. The paper presented core component or elements of the object of Industrial Socialisation in terms of constituent of cognitive orientation to be gained in industrial socialization process which include: History of organization, culture, ecology, goals and objectives, career path, output, changes etc. The authors assumed that industrial socialization determines role performance of employee. Consequently, present industrial socialization role performance matrix which indicates that managerial staff requires 70% and above cognitive orientation developed through socialization process to invoke high affective and evaluative orientation in order to produce natural motivation that enhances high and efficient role performance, while supervisory/technical staff requires 60% and clerical/artisan 50%. The paper recommended the replacement of training and retraining in industrial sociology literature with industrial socialization and resocialisation. The paper also recommends allocation of adequate resources for strategic development of employee socialization strategy in every modern organization as well as utilization of industrial sociologists as experts in designing, implementing, evaluating industrial socialization strategy in organization to enhance efficient and effective role performance by employees to boost organizational productivity, adjustment to change, as well as growth and development. -

SOCIAL STRATIFICATION Edited by Dr

SocialStratification DSOC202 Edited By Dr. Sukanya Das SOCIAL STRATIFICATION Edited By Dr. Sukanya Das Printed by USI PUBLICATIONS 2/31, Nehru Enclave, Kalkaji Ext., New Delhi-110019 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara CONTENT Unit 1: Understanding Social Stratification 1 Rosy Hastir, Lovely Professional University Unit 2: Basic Concepts Relating to Stratification 13 Rosy Hastir, Lovely Professional University Unit 3: Theories of Social Stratification-I 31 Rosy Hastir, Lovely Professional University Unit 4: Theories of Social Stratification-II 47 Rosy Hastir, Lovely Professional University Unit 5: Forms of Social Stratification 70 Rosy Hastir, Lovely Professional University Unit 6: Caste 96 Rosy Hastir, Lovely Professional University Unit 7: Class 117 Rosy Hastir, Lovely Professional University Unit 8: Race and Ethnicity 166 Rosy Hastir, Lovely Professional University Unit 9: Gender and Stratification 175 Sukanya Das, Lovely Professional University Unit 10: Women's Empowerment 202 Sukanya Das, Lovely Professional University Unit 11: Social Mobility 230 Sukanya Das, Lovely Professional University Unit 12: Mobility in Closed and Open Systems of Stratification 249 Sukanya Das, Lovely Professional University Unit 13: Changing Dimensions of Social Stratification 257 Sukanya Das, Lovely Professional University Unit 14: Emergence of Middle Class System 295 Sukanya Das, Lovely Professional University SYLLABUS Social Stratification Objectives 1. To familiarize the student about the concept of social stratification. 2. To familiarize the -

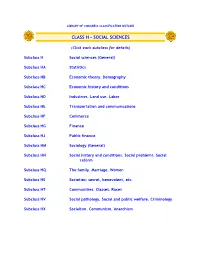

Library of Congress Classification Outline: Class H

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CLASSIFICATION OUTLINE CLASS H - SOCIAL SCIENCES (Click each subclass for details) Subclass H Social sciences (General) Subclass HA Statistics Subclass HB Economic theory. Demography Subclass HC Economic history and conditions Subclass HD Industries. Land use. Labor Subclass HE Transportation and communications Subclass HF Commerce Subclass HG Finance Subclass HJ Public finance Subclass HM Sociology (General) Subclass HN Social history and conditions. Social problems. Social reform Subclass HQ The family. Marriage. Women Subclass HS Societies: secret, benevolent, etc. Subclass HT Communities. Classes. Races Subclass HV Social pathology. Social and public welfare. Criminology Subclass HX Socialism. Communism. Anarchism Subclass H H1-99 Social sciences (General) Subclass HA HA1-4737 Statistics HA29-32 Theory and method of social science statistics HA36-37 Statistical services. Statistical bureaus HA38-39 Registration of vital events. Vital records HA154-4737 Statistical data HA154-155 Universal statistics HA175-473 By region or country Subclass HB HB1-3840 Economic theory. Demography HB71-74 Economics as a science. Relation to other subjects HB75-130 History of economics. History of economic theory Including special economic schools HB131-147 Methodology HB135-147 Mathematical economics. Quantitative methods Including econometrics, input-output analysis, game theory HB201-206 Value. Utility HB221-236 Price HB238-251 Competition. Production. Wealth HB501 Capital. Capitalism HB522-715 Income. Factor shares HB535-551 Interest HB601 Profit HB615-715 Entrepreneurship. Risk and uncertainty. Property HB801-843 Consumption. Demand HB846-846.8 Welfare theory HB848-3697 Demography. Population. Vital events HB3711-3840 Business cycles. Economic fluctuations Subclass HC HC10-1085 Economic history and conditions HC79 Special topics Including air pollution, automation, consumer demand, famines, flow of funds, etc. -

Industrialisation, Class Formation and Social Mobility in Ireland

Proceedings of the British Academy, 79, 105-128 Industrialisation, Class Formation and Social Mobility in Ireland CHRISTOPHER T. WHELAN,* RICHARD BREENt & BRENDAN J. WHELAN* * Economic & Social Research Institute, Dublin t The Queen’s University of Belfast Industrialisation and Social Mobility FEWSOCIETIES have changed so rapidly and so radically as has the Republic of Ireland since 1960. Success in the form of state initiatives to promote industrialisation brought a more general promise that the fruits of indepen- dence would finally be realised. The associated expectations and excite- ment were captured in the catch phrase of the 1960s ‘the rising tide that would raise all boats’. Such a sanguine view of the relationship between economic growth and social mobility was, until recently, shared by the bulk of sociologists. In fact, as Goldthorpe (1985: 554) concludes, the evidence on which such confident conclusions regarding the relationship between economic growth, industrialisation and social mobility are based is ‘confused and uncertain’. In the literature of the late 1950s and 1960s the discussion of mobility in industrial societies was linked with the question of whether American society was distinctive in the amount of social mobility it displayed. The conclusion reached by Lipset and Bendix (1959) and Blau and Duncan (1967) was that economically advanced societies had in common a level of mobility which is, by any reckoning, high. To explain the strikingly similar ‘total vertical mobility rates’, Lipset and Bendix sought factors universal throughout industrial societies. Among the pro- cesses inherent in all modern social structures which, they argue, have a direct effect on the rate of social mobility, two in particular are of importance: (i) changes in the number of available vacancies, and (ii) Read 7 December 1990. -

Xorox University Microfilms 300 North Z W B Rood Ann Arbor, Michigan 4310# 75-3066

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological maans to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.