Note to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interviews with Hugo Blanco, Other Exiles, on Right-Wing Junta's Repression · -Pages 5-7

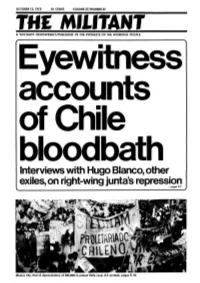

OCTOBER 12, 1973 25 CENTS VOLUME 37/NUMBER 37 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE II Interviews with Hugo Blanco, other exiles, on right-wing junta's repression · -pages 5-7 Mexico City. Part of demonstration of 100,000 to protest Chile coup. U.S. protests, pages 9, 10. ln.Briel MICHIGAN STUDENTS OPPOSE TUITION HIKE: Stu in San Francisco last March of the tenth anniversary dents at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor are of the CIA-backed coup that brought the shah of Iran THIS organizing a tuition strike to roll back a 24 percent fee to power. hike passed by the board of regents this summer. Widespread protests forced the dropping of the assault WEEK'S The Student Action Committee, which is coordinating charges. But Shokat and Ghaemmagham pleaded guilty the strike, held a rally of 250 students on Sept. 28, despite to the lesser charge of "intimidation" to bring the case MILITANT pouring rain. Militant correspondent Marty Pettit reports to an end. 3 UFW-Teamster talks the protesters then lined up in front of collection windows ·The Iranian Student Association has urged protests 4 Boudin describes gov't in the registration area and successfully prevented cashiers against these sentences, especially the imposition of the from accepting payments. maximum jail term on Shokat. Write to: Honorable Judge attempts to discredit him Strike leader Ruy Teixeira said, "A lot of people see this Williams, Federal Building, Nineteenth Floor, 450 Golden 8 New evidence of mass whole struggle, which hopefully will become nationwide, Gate Ave., San Francisco, <_::alif. -

Daniel Gilbert & Anton Kristiansson

xand • Ale er Dur en efe kin lt as • M T Nummer 10 • 2009 Sveriges största musiktidning i l • d n e o h i s H i j V e l s m i h • T O • a s k u w i o c o u L d • • I k s a Daniel GIlBert & AntoN KristianssoN Det gamla och det nya – samma Göteborg Joel Alme Pascal Fuck Buttons Bästa musiken 2009 Bibio Nile Dälek Up North Tildeh Hjelm This Is Head Riddarna 5 Årets album 7 Årets låtar Är trovärdighet på 8 Om autotunen må ni berätta väg ut? 8 Skivbolaget som blev ett fanzine Jag måste erkänna att jag vacklat i min tro illa om Henrik Berggren om han levt ett glas- på sistone. En tro som säger mig att trovär- sigt stekarliv. Att leva som man lär har sin ledare dighet i musiken är lika viktigt som i livet. Är poäng. Tycker jag. 10 Blågult guld det då så eller är jag bara en verklighetsfrån- I hiphopvärlden har trovärdighet å vänd drömmare? andra sidan varit A och O från dag ett. Där innehåll Riddarna Tankarna kring den vacklande trovärdig- förväntas man rappa om det man varit med hetssträvan kom till mig på en cykeltur till om. Att ha langat knark med ena handen på This Is Head kontoret. Jag tänkte på hårdrockare som pistolkolven är standard. Kulhålen ska finnas sjunger om Satan, döden, krig och annat där som bevis, liksom. Men det är lätt att Tildeh Hjelm hemskt. Kan det verkligen vara sant att så stelna i en form, och inte vilja utvecklas. -

Issue 171.Pmd

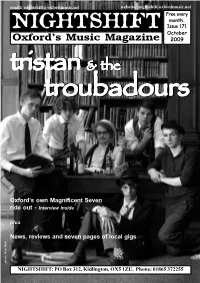

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 171 October Oxford’s Music Magazine 2009 tristantristantristantristan &&& thethethe troubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadourstroubadours Oxford’s own Magnificent Seven ride out - Interview inside plus News, reviews and seven pages of local gigs photo: Marc West photo: Marc NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net THIS MONTH’S OX4 FESTIVAL will feature a special Music Unconvention alongside its other attractions. The mini-convention, featuring a panel of local music people, will discuss, amongst other musical topics, the idea of keeping things local. OX4 takes place on Saturday 10th October at venues the length of Cowley Road, including the 02 Academy, the Bullingdon, East Oxford Community Centre, Baby Simple, Trees Lounge, Café Tarifa, Café Milano, the Brickworks and the Restore Garden Café. The all-day event has SWERVEDRIVER play their first Oxford gig in over a decade next been organised by Truck and local gig promoters You! Me! Dancing! Bands month. The one-time Oxford favourites, who relocated to London in the th already confirmed include hotly-tipped electro-pop outfit The Big Pink, early-90s, play at the O2 Academy on Thursday 26 November. The improvisational hardcore collective Action Beat and experimental hip hop band, who signed to Creation Records shortly after Ride in 1990, split in outfit Dälek, plus a host of local acts. Catweazle Club and the Oxford Folk 1999 but reformed in 2008, still fronted by Adam Franklin and Jimmy Festival will also be hosting acoustic music sessions. -

A Estética Grotesca Da Banda Cicuta E a Representação Poética Transmidiática Na Obra Viver Até Morrer

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE ARTES VISUAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ARTE E CULTURA VISUAL MESTRADO O INFERNO É AQUI: A ESTÉTICA GROTESCA DA BANDA CICUTA E A REPRESENTAÇÃO POÉTICA TRANSMIDIÁTICA NA OBRA VIVER ATÉ MORRER FREDERICO CARVALHO FELIPE Goiânia/GO 2015 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE ARTES VISUAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ARTE E CULTURA VISUAL MESTRADO O INFERNO É AQUI: A ESTÉTICA GROTESCA DA BANDA CICUTA E A REPRESENTAÇÃO POÉTICA TRANSMIDIÁTICA NA OBRA VIVER ATÉ MORRER FREDERICO CARVALHO FELIPE Dissertação apresentada à Banca Examinadora do Programa de Pós- Graduação em Arte e Cultura Visual – Mestrado da Faculdade de Artes Visuais da Universidade Federal de Goiás, como exigência parcial para a obtenção do título de MESTRE EM ARTE E CULTURA VISUAL, sob orientação da Profa. Dra. Rosa Maria Berardo. Linha de pesquisa: Poéticas Visuais e Processos de Criação. Goiânia/GO 2015 TERMO DE CIÊNCIA E DE AUTORIZAÇÃO PARA DISPONIBILIZAR AS TESES E DISSERTAÇÕES ELETRÔNICAS (TEDE) NA BIBLIOTECA DIGITAL DA UFG Na qualidade de titular dos direitos de autor, autorizo a Universidade Federal de Goiás (UFG) a disponibilizar, gratuitamente, por meio da Biblioteca Digital de Teses e Dissertações (BDTD/UFG), sem ressarcimento dos direitos autorais, de acordo com a Lei nº 9610/98, o documento conforme permissões assinaladas abaixo, para fins de leitura, impressão e/ou download, a título de divulgação da produção científica brasileira, a partir desta data. 1. Identificação do material bibliográfico: [ ] Dissertação [x ] Tese 2. Identificação da Tese ou Dissertação Autor (a): Frederico Carvalho Felipe E-mail: [email protected] Seu e-mail pode ser disponibilizado na página? [x]Sim [ ] Não Vínculo empregatício do autor Agência de fomento: Sigla: Capes País: Brasil UF: GO CNPJ: Título: O inferno é aqui: a estética grotesca da banda Cicuta e a representação poética transmidiática na obra ‘Viver até Morrer’. -

PTA 1-87 Ammi111mr 1St MAB Units Enhance Skills More Than 1,400 Marines PTA 1-87

of Serving MCAS K neohe Bay, 1st IVIAB, Camp Smith and Marine Barracks, Hawaii ebtu.si'y l y 1997, PTA 1-87 AMMI111Mr 1st MAB units enhance skills More than 1,400 Marines PTA 1-87. During the first few and sailors of the 1st MAB days, the "cannon cockers" particpated in PTA exercise 1- conducted battery-level train- 87 at the Pohakuloa Training ing, then moved on to fire their Area on Hawaii, Jan. 12-29. 155mm and 105mm howitzers In general, the 1st MAB in a battalion-level exercise. sends units to PTA twice a Later, 1/12 conducted evalua- year for training at the spra- tions of key elements of the wling Army facility on the Big battalion, using the strict Island. PTA provides 57,000 standards of the Marine Corps acres of live-fire impact area Combat Readiness Evalua- and an additional 52,000 acres tion System. for maneuver in the rolling, Joining 1/12 for the exercise mountainous central area of was Battery R, 5/11, visiting Hawaii. from the 7th MAB headquar- The Marines of the PTA 1-87 tered at the Marine Corps Air Task Force put the training Ground Combat Center, 29 opportunity to good use, exer- Palms, Calif. 1st MAB's artil- cising infantry, aviation, lerymen loaned "Romeo Bat- artillery and service support tery" some 105mm howitzers units throughout the nearly for the deployment and pro- three-week deployment. vided other support. Marines of 2/3 provided the Throughout the exercise, primary ground maneuver Marines from BSSG-1 pro- element. -

Jon Theodore

12 Modern Drummer June 2014 Booth #1219 Always on the go, Daru Jones desired a highly portable cymbal set for hip-hop sessions, DJ Jams, and other sit-ins that spontaneously present themselves, enabling him to preserve his personal sound in modern urban mobility. The concept was developed in the PST X series, which provides a suitable basis for the type of fast and dry sounds that perfectly fit the world of Hip-hop & Electronica percussion. It is executed with the DJs 45 set consisting of a 12" Crash, 12" Ride and 12" Hats. INTRODUCING ?MbcRaf^aYbE^]WPERZRPcEVRZZDRPW_Rb͜ŬeRQWbcW]PcZh d]W`dRS^a\dZMb͜QRbWU]RQ͜PaRMcRQM]QcRbcRQc^_RaS^a\ ^_cW\MZZhW]cVRR]eWa^]\R]ccVMcORMabWcb]M\R͙ studio heritage modern dry stadium urban ?MbcRaf^aYbGaOM]bVRZZbSRMcdaRMa^d]QRQ ʎORMaW]URQUR P^\OW]RQfWcV^da6eR]BZhEWgOZR]Q^S3WaPVΧ8d\Χ3WaPVfWcV?M_ZR aRW]S^aPR\R]caW]Ubc^_a^\^cR_a^]^d]PRQZ^fR]QMccMPYfWcV b\^^cV͜ReR]QRPMh͙Ada\W]W\MZP^]cMPcEF>bfWeRZZdUb͜P^\OW]RQ fWcV^da ͙ \\Ed_Ra:^^_ZZhoops increase projection without W\_RQW]U_RaS^a\M]PRMPa^bbcVRcd]W]Ub_RPcad\͙ FVWbWbcVRWQRMZb^d]QS^aB^_͜D̿3^a8^b_RZ͙ ?MbcRaf^aYbGaOM]bV^f]W]ORMdcWSdZ3ZMPY lacquer fWcV:^Z^UaM_VWPůMYRb͙>WbcR]c^cVR GaOM]aRPW_R_ZMhRQOh3aWM]7aMbWRa?^^aR Mc_RMaZQad\͙P^\ CONTENTS Volume 41 • Number 12 CONTENTS Cover and Contents photos by Andreas Neumann FEATURES 28 MODERN DRUMMER 2018 56 ELI KESZLER READERS POLL The multidisciplinary artist has Make your voice heard in the most dedicated much of his career important poll in the drumming to exploring the solo drumset’s world! expressionistic capabilities, leading to new creative and career 30 THE PSYCHEDELIC FURS’ opportunities. -

O Inferno É Aqui: a Estética Grotesca Da Banda Cicuta E a Representação Poética Transmidiática Na Obra Viver Até Morrer

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE ARTES VISUAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ARTE E CULTURA VISUAL MESTRADO O INFERNO É AQUI: A ESTÉTICA GROTESCA DA BANDA CICUTA E A REPRESENTAÇÃO POÉTICA TRANSMIDIÁTICA NA OBRA VIVER ATÉ MORRER FREDERICO CARVALHO FELIPE Goiânia/GO 2015 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE ARTES VISUAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ARTE E CULTURA VISUAL MESTRADO O INFERNO É AQUI: A ESTÉTICA GROTESCA DA BANDA CICUTA E A REPRESENTAÇÃO POÉTICA TRANSMIDIÁTICA NA OBRA VIVER ATÉ MORRER FREDERICO CARVALHO FELIPE Dissertação apresentada à Banca Examinadora do Programa de Pós- Graduação em Arte e Cultura Visual – Mestrado da Faculdade de Artes Visuais da Universidade Federal de Goiás, como exigência parcial para a obtenção do título de MESTRE EM ARTE E CULTURA VISUAL, sob orientação da Profa. Dra. Rosa Maria Berardo. Linha de pesquisa: Poéticas Visuais e Processos de Criação. Goiânia/GO 2015 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE ARTES VISUAIS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ARTE E CULTURA VISUAL MESTRADO O INFERNO É AQUI: A ESTÉTICA GROTESCA DA BANDA CICUTA E A REPRESENTAÇÃO POÉTICA TRANSMIDIÁTICA NA OBRA VIVER ATÉ MORRER FREDERICO CARVALHO FELIPE BANCA EXAMINADORA: ________________________________ Profa. Dra. Rosa Maria Berardo Orientadora e presidente da banca – FAV/UFG ________________________________ Prof. Dr. Edgar Silveira Franco Membro interno – FAV/UFG ________________________________ Prof. Dr. Daniel Christino Membro externo – FIC/UFG ________________________________ Prof. Dr. Thiago Fernando Sant'Anna e Silva Suplente interno – FAV/UFG ________________________________ Profa. Dra. Maria Luiza Martins de Mendonça Suplente externo - FIC/UFG RESUMO O objetivo deste trabalho consiste em contribuir com os estudos relativos à estética do grotesco no rock’n’roll e à utilização de diferentes plataformas midiáticas como forma de estilização poética e criação de narrativas convergentes à obra Viver até Morrer da banda Cicuta. -

The St. Nicholas Christmas Book

CHRISTMAS BOOK REFERENCE 5t- Nichols Chnstrr***, booK NY PUBLIC LIBRARY THE BRANCH LIBRARIES 3 3333 02155 6424 THE MARY GOULD DAVIS COLLECTION THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY The St. Nicholas Christmas Book THE CHRISTMAS LIGHTS. The St. Nicholas Christmas Book Merry Christmas ! New York : The Century Co. 1899 Copyright, 1874, 1881, 1883, 1885, 1886, 1887, 1888, 1889, 1890, 1891, 1892, 1893, 1894, 1895, 1896, 1897, 1898, by THE CENTURY Co. Copyright, 1899, by THE CENTURY Co. THE De VINNE PRESS. C PROPERTY OF THE CITY OF NEW YOM Contents PAGE DECEMBER i PRESIDENT FOR ONE HOUR 4 MAID BESS 19 MAX AND THE WONDER-FLOWER 23 A DEAR LITTLE SCHEMER 26 How THE SECRETARY OF THE TREASURY ONCE PLAYED SANTA CLAUS . 28 SNAP-SHOTS BY SANTA CLAUS 32 VISIT ST. "A FROM NICHOLAS" 35 SANTA CLAUS' PATHWAY 36 THE FOOL'S CHRISTMAS 44 MERRY CHRISTMAS 47 A RANDOM SHOT - 48 BENEVOLENT BOY 57 A RACE WITH AN AVALANCHE 59 THE CHRISTMAS SLEIGH-RIDE 65 A NEW-FASHIONED CHRISTMAS 66 WHERE THE CHRISTMAS-TREE GREW 68 How A STREET-CAR CAME IN A STOCKING 77 THE TARDY SANTA CLAUS 87 THE PICTURE 89 THE ELFIN BOUGH 90 CHRISTMAS IN BETHLEHEM 94 MISPLACED CONFIDENCE I0 2 "THE CHRISTMAS INN" 104 WAITING FOR SANTA CLAUS 112 MOLLY RYAN'S CHRISTMAS EVE 117 SANTA CLAUS STREET IN JINGLETOWN 124 VII CONTENTS PAGE CHRISTMAS ON THE "POLLY" . , 126 A GENTLE REMINDER 129 ' "THIS is SARAH JANE COLLINS" 130 THE CHRISTMAS-TREE LIGHTS ... .... 136 A CHRISTMAS GOBLIN 138 LONDON CHRISTMAS PANTOMIMES 140 IF You 'RE GOOD 155 SANTA CLAUS AND THE MOUSE 156 THE BEST TREE 158 COUSIN JANE'S MISTAKE 160 YE MERRIE CHRISTMAS FEAST 173 SANTA CLAUS' PONY 176 THE WANDERING MINSTREL 182 THE BLOOM OF THE CHRISTMAS-TREE 184 A CHRISTMAS-EVE THOUGHT 185 A CHRISTMAS WHITE ELEPHANT 186 OSMAN PASHA AT BUCHAREST 204 A SNOW-BOUND CHRISTMAS 206 A SANTA CLAUS MESSENGER BOY 217 CHRISTMAS EVE . -

Commercial Ïeaôer $50.000 of Gifts It Has Icceived Special All«) SM I I II H I I ! I

Play *Rummage SaleV See Our Classified Page Today 7 K ¿ * u { ~ c < i South Bergen will he * • • O n t S P r e n tis s H o u se at 244 M o ntross A v r m .r c e n te r o f m e tro p o lita n v(M i»*t\ ha- n< «■[ leig h D ic k in s o n L’nive-r-ut \ T h e ¡7 ; < . »■ 1 0 18th Century style, will be u-ed foi f, , (i \ \ i m w il k nar rooms The* univers:t\ will > • Commercial ïeaôer $50.000 of gifts it has icceived Special all«) SM I I II H I I ! I . I \ I ! I \ 11 \\ th e architecture of the home. ,> heing hi \..l I ■ > V, U 1 ï N DU I RST. \ I I KHIU u n r, I «*»,1. TÉLÉPHONÉ CÉNEVA «.«TOO-STO' The W ay Lincoln School Once Looked Two Girls Hit On Ridge Road Storm Swamps Little League Field, An automooile ope: ated by a Nutlev drive: ran down 2 I.ynd - ’¡•irst giids ,,t Ridge* R o a d and S \th Avenue Thursday night The accident took \ ¡a-e neai But It W ill Live To See The Season the office of I)| \’ 1 nt e-it F e t t e w ho tr rated hoth girls I lie I id le I e.jgu»-'« I »a -«• - One nt the girls was Rosalyfi Kail fieM o|| Rl\er*n|e \\e- D Andiea, 15. -

Curt Magazin Nürnberg

Es spielen ganz groß auf: MICHI MELCHNER, R ABE BIRD BERLIN, LA-BOUM, FUSSBALLLT - ER! WILDSTYLE-EKKI, SERKan‘s We ELT HI FÜR DIE EN CLUB SURPRISE (siehe Bild) E MUSIK SPI DI ACHTLEB u.v.a. ... und der Nerd ERGS N vom CURT ist mit NÜRNB von der Partie! KICKT AUCHENTLICH! IM JUNI curt Magazin Nürnberg ORD #145 ---- JUNI 2010 ---- WWW.CURT.DE ICH VERLOSE 4 TICKETS DONNERSTAG 03.06. SAMSTAG 05.06. SONNTAG 06.06. ÜBER CURT.DE!!! IRRE!!! CENTERSTAGE CENTERSTAGE CENTERSTAGE 19:30 TURBOSTAAT 13:30 HALESTORM 14:20 WE ARE THE FALLEN 21:00 RAGE AGAINST THE MACHINE 14:25 AIRBOURNE 15:05 H-BLOCKX 15:55 SLASH 16:10 WOLFMOTHER FREITAG 04.06. 17:25 CYPRESS HILL 17:35 GOSSIP CURT.DE 19:05 JAY-Z 19:20 30 SECONDS TO MARS CENTERSTAGE 21:00 KISS 21:15 MUSE 14:15 FIVE FINGER DEATH PUNCH 15:05 PENDULUM ALTERNASTAGE ALTERNASTAGE 16:15 BULLET FOR MY VALENTINE 12:45 ROMAN FISCHER 13:50 LAZER 17:45 IN EXTREMO 13:30 FERTIG, LOS! 14:45 HELLYEAH 19:15 RISE AGAINST 14:20 LISSIE 15:40 AS I LAY DYING GRATULIERT ZU 15 JAHREN 21:30 RAMMSTEIN 15:15 ELLIE GOULDING 16:45 LAMB OF GOD 16:15 THE SOUNDS 17:50 STONE SOUR ALTERNASTAGE 17:20 KATE NASH 19:05 ALICE IN CHAINS 13:35 CARPARK NORTH 18:30 KASABIAN 20:30 VOLBEAT ROGRAMM 14:25 CANCER BATS 19:45 EDITORS 22:00 SLAYER 15:15 A DAY TO REMEMBER P 21:25 SPORTFREUNDE STILLER 23:45 MOTÖRHEAD 16:05 DIZZEE RASCAL 23:30 JAN DELAY & DISKO NO. -

O/Violating Lawslroh Theater As Compiled by the I Third Arrested Waiting in Grosse Pointe News ' Dance 'I: Car Ionwoods Lot; C~N- at Teeners

All the News Every Thursday Morning of All the Pointes rosse ~ws Complete Netl'S Covera~e of All tlte Poiutes Home of the News VOl. 2b-NO. 4 Entered as Second Clas~ Matter at $5.00 Per Year the Post OfTlce at Detroit, Mich. GROSSE POINTE, MICHIGAN, JANUARY 28, 1965 lOc Per Copy 20 Pages Two Sections-Section One - • iPair Nabbed DEADLINES High School Musicians Draw Big Crowd of the Two Found GutltYIAttempting to WEEK O/Violating LawslRoh Theater As Compiled by the I Third Arrested Waiting in Grosse Pointe News ' Dance 'I: Car IonWoods Lot; C~n- At Teeners . fesslons Made By Tno Thursday, January 21 :' IT WAS PRESIDENT Lyndon I -----.-- Three Detroit men were B. Johnson's day yesterday. ,Owner of Haii and Youth Who Organized Party Pay arraigned for examination After reciting his oath of office, $/00 Fines and Costs; 90-Day Sentence f"r before Woods Judge Don delivering his inaugural address Former Suspended by Judge Goodrow, Monday evening, and watching the parade in his honor. he attended five balls Th f H TJ 11 20542 H January 25, on warrants held in leading hotels in Wash- e owner 0 arper .l.loa, arper avenue, charging them with damag- ington. In his address to the Harper Woods, and a Pointe teenager, were found guilty ing a safe in the Woods nation and the world he asked in Harper Woods Municipal Court on Tuesday, January Theater, 19269 IVLck ave- for justice. libc;,ty and unity 19, of liquor vjolation charges. The hearing was held nue, after the theater was among Americans and our "fe]. -

Hightstown Gazette

H ightstown Gazette. 97th YEAR—NUMBER ii HIGHTSTOWN, ilERCER COUNTY, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, AUGUST 2, 1945 PRICE—FIVE CENTS Girl Migrant Man Fatally Hurt CentraiPotatoFarmersFace NEWS OF OUR Gets Jail Term In Auto Crash on Heavy Loss With Favorable ■ MEN«tfWOMEN For Cutting Fray Freehold Road Markets Fast Disappearing IN UNIFORM 30 Stitches Required to Sew Passenger Injured When Cut on Victim’s Neck; Auto Strikes Pole After August Starts Off Where Shipments Reduced to 16 July Left Off— W ith Rain! Frank Perrine in School for Transferred to Pacific 15 Cases Handled in Court Driver Dozes at Wheel Instead of 1200 Carloads Will the month of August be any bet Mine Warfare Training Ruby Smith, 18-year-oId migrant Ne- Charles J. Griffiths, 59 years oUl, of ter than July with its rainy and muggy Because of Wet Grounds I’enn Argyl, Pa., died Sunday night in weather July’s total rainfall was over Franklin B. Perrine, 21, motor ma Kro, was sentenced to serve 90 days in nine inches. Perhaps there was at least Instead of a weekly shipment of 1,200 chinist’s mate, second class, USNR, the Mercer County jail by Recorder F. St. Francis Hospital, Trenton, of in one clear day. The weather observer carloads, potato dealers of New Jersey’s Route 1, Cream Ridge, is at the mine- K. Hampton in Recorder’s Court M on juries suffered in an automobile acci listed must of the 31 days as rainy or famed potato belt—Middlesex, M ercer craft training center, Little Creek, Va., day night.