Plan Lazo: Evaluation and Execution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Future of US-Colombia Relations

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons Jack Gordon Institute Research Publications 2019 The Future of US-Colombia Relations Christopher Sabatini Sofia Mateu-Gelabert Brian Fonseca Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/jgi_research Part of the International and Area Studies Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Sabatini, Christopher; Mateu-Gelabert, Sofia; and onseca,F Brian, "The Future of US-Colombia Relations" (2019). Jack Gordon Institute Research Publications. 30. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/jgi_research/30 This work is brought to you for free and open access by FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jack Gordon Institute Research Publications by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FUTURE OF U.S.- COLOMBIAN RELATIONS The Future of U.S.-Colombian Relations Table of Contents 3 Introduction 4 Politics and Public Opinion 7 Security 9 Shifting Security Challenges 11 Economy 14 U.S.— Colombia Diplomatic Relations Multilateral Relations 15 An Outlier: Venezuela’s Future and Venezuelan Refugees 17 The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Scenarios for Colombia by 2030 18 Recommendations The following report is part of the Florida International University—United States Southern Command Academic Partnership. United States Southern Command provides funding to support this series as part of its academic outreach efforts. Academic outreach is intended to support United States Southern Command with new ideas, outside perspectives, and spark candid discussions. The views expressed in this findings report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Government, United States Southern Command, Florida International University, or any other affiliated institutions. -

Redalyc.History of the Colombian Left-Wings Between 1958 and 2010

Revista Tempo e Argumento E-ISSN: 2175-1803 [email protected] Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina Brasil Archila, Mauricio; Cote, Jorge History of the Colombian left-wings between 1958 and 2010 Revista Tempo e Argumento, vol. 7, núm. 16, septiembre-diciembre, 2015, pp. 376-400 Universidade do Estado de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=338144734018 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative e ‐ ISSN 2175 ‐ 1803 History of the Colombian left‐wings between 1958 and 20101 Abstract This article looks at the history of left‐wings in Colombia, Mauricio Archila framed within what was happening in the country, Latin Ph.D. and Professor in the Graduate program at America, and the world between 1958 and 2010. After the Universidad Nacional, in Bogotá, and specifying what we mean by “left‐wings” and outlining their associate researcher of the CINEP. background in the first half of the 20th century, there is a Colombia. panorama of five great moments of the period under study to [email protected] reach the recent situation. The chronology favors the internal aspects of the history of Colombian left‐wings, allowing us to appreciate their achievements and limitations framed into Jorge Cote such a particular context as the Colombian one. MA student in History at the Universidad Nacional, in Bogotá. Keywords: Colombia; Left‐wings; Guerrillas; Social Colombia. -

JORGE ELIECER GAITAN.Pdf

JORGE ELIECER GAITÁN: TRAYECTORIA E IDEOLOGIA DE UN CAUDILLO LIBERAL EDGAR EDUARDO FRANCO TORRES UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE COLOMBIA UNIVERSIDAD DE SALERNO ITALIA Bogotá, Colombia. 2012 1 JORGE ELIECER GAITÁN: TRAYECTORIA E IDEOLOGIA DE UN CAUDILLO LIBERAL EDGAR EDUARDO FRANCO TORRES Trabajo de grado para obtener el título de Máster en Ciencia Política de la Universidad Católica de Colombia y la Universidad de Salerno de Italia. Asesoría Dr. Miguel A. Infante D. Coordinador Académico Maestría UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE COLOMBIA UNIVERSIDAD DE SALERNO ITALIA Bogotá, Colombia. 2012 2 DEDICATORIA A mi padre del partido liberal y a mi madre del partido conservador que vivieron la década de los años 40. 3 AGRADECIMIENTOS Agradezco a la Universidad Católica de Colombia, por haberme brindado darme la oportunidad de cursar un programa a académico de tan alto prestigio y calidad como lo es el de la maestría en ciencia política en convenio con la Universidad de Salerno de Italia. De igual forma Agradezco a los directivos del Programa Doctores Antonio Scoccozza y. Miguel Infante, por su paciencia, confianza y ánimo en la elaboración del trabajo de grado, así como todo el entusiasmo impreso en el diseño y desarrollo del programa. A mis seres queridos y amigos que me dieron el impulso constante para lograr salir adelante con este trabajo. A todas y cada una de las personas que me colaboraron activamente para la realización de este documento. 4 RESUMEN Jorge Eliecer Gaitán creador del movimiento Gaitanista, el cual fue dirigido por Gloria Gaitán (su hija), cuya sede se encontraba ubicada en el barrio las Cruces de Bogotá, hoy hace parte de un importante fragmento de la historia colombiana. -

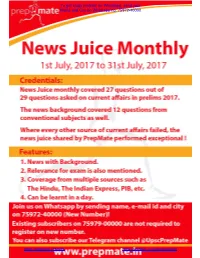

To Get Study Material on Whatsapp, Send Your Name and City on Whatsapp No

To get study material on Whatsapp, send your Name and City on Whatsapp no. 75972-40000 https://prepmate.in/books/ https://telegram.me/upscprepmate To get study material on Whatsapp, send your Name and City on Whatsapp no. 75972-40000 https://prepmate.in/books/ https://telegram.me/upscprepmate To get study material on Whatsapp, send your Name and City on Whatsapp no. 75972-40000 Table of Contents Polity And Governance ....................................................................................................................... 1 1. Cutting down tribunals (Relevant for GS Prelims, GS Mains Paper II) ............................... 1 2. SC allows abortion of ailing foetus (Relevant for GS Mains Paper II) ................................ 1 3. SC open to liquor sale on city highways (Relevant for GS Prelims, GS Mains Paper II) ............................................................................................................................................................................ 3 4. Selection of ECs must be transparent, SC tells Centre (Relevant for GS Prelims, GS Mains Paper II) ........................................................................................................................................... 4 5. Presidential Election, 2017 – Right to vote or not to vote (Relevant for GS Prelims, GS Mains Paper II) ........................................................................................................................................... 5 6. National Pension Service fortnight (Relevant for -

Capitulo Barranquilla

1 «Barranquilla me permitió ser escritor. Tenía la población inmigrante más elevada de Colombia – árabes, chinos, etcétera – era como Córdoba en la Edad Media. Una ciudad abierta, llena de personas inteligentes a las que les importaba un carajo ser inteligentes (…)‖ 1 Gabriel García Márquez 1 (Martin, 2009 p. 161) 2 INVESTIGACIÓN PERIODÍSTICA TRAS LAS HUELLAS DE MACONDO CAPITULO BARRANQUILLA INFORME FINAL Autor: MARÍA DEL PILAR RODRÍGUEZ SAUMET Periodista - Escritora Curadora de Arte *Gabitera Bogotá, Colombia 2014 3 INVESTIGACIÓN PERIODÍSTICA TRAS LAS HUELLAS DE MACONDO CAPITULO BARRANQUILLA INFORME FINAL Autor: MARÍA DEL PILAR RODRÍGUEZ SAUMET Periodista - Escritora Curadora de Arte *Gabitera Interventor: JOSÉ MANUEL PACHECO Gerente de Competitividad y Apoyo las Regiones (e) INVESTIGACIÓN FINANCIADA CON RECURSOS DEL FONDO DE PROMOCIÓN TURÍSTICA Y EL VICEMINISTERIO DE TURISMO DE LA REPÚBLICA DE COLOMBIA. Bogotá, Colombia 2014 4 Dedicatoria: Dedico las presentes líneas a Gabriel José de la Concordia García Márquez por haberle dado un único regalo a Colombia: La inmortalidad. 5 Agradecimientos: Agradezco al Fondo de Promoción Turística y al Vice – ministerio de Turismo de la República de Colombia por la confianza en este proyecto y los recursos para su ejecución; a Jaime Abello Banfi por su respaldo, lucidez y complicidad invaluable, a José Manuel Pacheco por su magnífica labor; a Jaime, David y Shani García-Márquez por todo el tiempo y el afecto compartido; a Elena Ponce por su dedicación y entrega. 6 Tabla de Contenidos: DEDICATORIA: 4 TABLA DE CONTENIDOS: 6 RESUMEN: 12 Introducción: 19 RECHACÉ UNA INVITACIÓN Y A CAMBIO ME REGALÓ UN LIBRO: 25 LA PRIMERA VEZ QUE LO VÍ SE NOS OLVIDÓ INVITARLO: 26 ¡QUE ESCRIBA LA QUE DICE QUE YO NO SÉ ESCRIBIR! 28 EL AMIGO QUE MÁS ME QUIERE… 30 EL ÚLTIMO ENCUENTRO: UN RETRATO HISTÓRICO. -

FARC-EP) Marxist-Leninist Insurgency Or Criminal Enterprise?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2005-12 The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia - People's Army (FARC-EP) Marxist-Leninist insurgency or criminal enterprise? Saskiewicz, Paul E. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/1809 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS THE REVOLUTIONARY ARMED FORCES OF COLOMBIA – PEOPLE’S ARMY (FARC-EP): MARXIST-LENINIST INSURGENCY OR CRIMINAL ENTERPRISE? by Paul E. Saskiewicz December 2005 Thesis Advisor: Jeanne Giraldo Co-Advisor: Douglas Porch Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 2005 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE: The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia – People’s Army (FARC- 5. FUNDING NUMBERS EP): Marxist-Leninist Insurgency or Criminal Enterprise? 6. -

Assessing the US Role in the Colombian Peace Process

An Uncertain Peace: Assessing the U.S. Role in the Colombian Peace Process Global Policy Practicum — Colombia | Fall 2018 Authors Alexandra Curnin Mark Daniels Ashley DuPuis Michael Everett Alexa Green William Johnson Io Jones Maxwell Kanefield Bill Kosmidis Erica Ng Christina Reagan Emily Schneider Gaby Sommer Professor Charles Junius Wheelan Teaching Assistant Lucy Tantum 2 Table of Contents Important Abbreviations 3 Introduction 5 History of Colombia 7 Colombia’s Geography 11 2016 Peace Agreement 14 Colombia’s Political Landscape 21 U.S. Interests in Colombia and Structure of Recommendations 30 Recommendations | Summary Table 34 Principal Areas for Peacebuilding Rural Development | Land Reform 38 Rural Development | Infrastructure Development 45 Rural Development | Security 53 Rural Development | Political and Civic Participation 57 Rural Development | PDETs 64 Combating the Drug Trade 69 Disarmament and Socioeconomic Reintegration of the FARC 89 Political Reintegration of the FARC 95 Justice and Human Rights 102 Conclusion 115 Works Cited 116 3 Important Abbreviations ADAM: Areas de DeBartolo Alternative Municipal AFP: Alliance For Progress ARN: Agencies para la Reincorporación y la Normalización AUC: Las Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia CSDI: Colombia Strategic Development Initiative DEA: Drug Enforcement Administration ELN: Ejército de Liberación Nacional EPA: Environmental Protection Agency ETCR: Espacio Territoriales de Capacitación y Reincorporación FARC-EP: Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia-Ejército del Pueblo GDP: Gross -

Ending Colombia's FARC Conflict: Dealing the Right Card

ENDING COLOMBIA’S FARC CONFLICT: DEALING THE RIGHT CARD Latin America Report N°30 – 26 March 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. FARC STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES................................................................... 2 A. ADAPTIVE CAPACITY ...................................................................................................................4 B. AN ORGANISATION UNDER STRESS ..............................................................................................5 1. Strategy and tactics ......................................................................................................................5 2. Combatant strength and firepower...............................................................................................7 3. Politics, recruitment, indoctrination.............................................................................................8 4. Withdrawal and survival ..............................................................................................................9 5. Urban warfare ............................................................................................................................11 6. War economy .............................................................................................................................12 -

Ending Colombia's FARC Conflict

ENDING COLOMBIA’S FARC CONFLICT: DEALING THE RIGHT CARD Latin America Report N°30 – 26 March 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. FARC STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES................................................................... 2 A. ADAPTIVE CAPACITY ...................................................................................................................4 B. AN ORGANISATION UNDER STRESS ..............................................................................................5 1. Strategy and tactics ......................................................................................................................5 2. Combatant strength and firepower...............................................................................................7 3. Politics, recruitment, indoctrination.............................................................................................8 4. Withdrawal and survival ..............................................................................................................9 5. Urban warfare ............................................................................................................................11 6. War economy .............................................................................................................................12 -

In/Security in Context: an Inquiry Into the Relational and Contextual Dimensions of In/Security Within

IN/SECURITY IN CONTEXT An inquiry into the relational and contextual dimensions of in/security within the Colombian peace process A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2017 Caroline Delgado School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Table of Contents List of Maps .......................................................................................................................... 8 List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ 8 List of Acronyms .................................................................................................................. 9 Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 11 Declaration .......................................................................................................................... 12 Copyright Statement .......................................................................................................... 13 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. 14 Dedication ........................................................................................................................... 15 CHAPTER ONE: Introduction ........................................................................................ 17 1.1 An Abstract of Everyday -

Bee Round 3 Bee Round 3 Regulation Questions

NHBB Nationals Bee 2018-2019 Bee Round 3 Bee Round 3 Regulation Questions (1) This man's alleged last words were \The battle is at its height - wear my armor and beat my war drums. Do not announce my death." After his death, this man was given the title Chunmugong. A double agent plot led to the removal of this man in favor of a commander who was decisively defeated at the Battle of Chilchonryang. This man was killed during his final victory at the Battle of Noryang, after he defeated 330 Japanese ships with 13 at the Battle of Myeongnyang. For the point, name this \Nelson of the East", a Korean admiral who championed turtle ships. ANSWER: Yi Sun-Sin (2) A politician with this surname, the rival of Dave Pearce, had an affair with burlesque performer Blaze Starr. The Wall Street Journal, jokingly labeled a politician with this surname the \fourth branch of government" due to the immense power he wielded as chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. That man's father, another politician with this surname, was assassinated by Carl Weiss. The \Share Our Wealth Plan", which called for making \Every Man A King", was formulated by a member of, for the point, what Louisiana political dynasty whose members included Earl, Russell, and Huey? ANSWER: Long (accept Earl Long; accept Russell Long; accept Huey Long) (3) This region's inhabitants launched raids against its northern neighbors, called \harvesting the steppes," to fuel its slave trade, which was based out of Kefe. Haci Giray [ha-ji ge-rai] established this region's namesake khanate after breaking off from the Golden Horde. -

Consolidating “Consolidation” Colombia’S “Security and Development” Zones Await a Civilian Handoff, While Washington Backs Away from the Concept

Consolidating “Consolidation” Colombia’s “security and development” zones await a civilian handoff, while Washington backs away from the concept by Adam Isacson WOLA Senior Associate for Regional Security Policy WOLA WASHINGTON OFFICE ON LATIN AMERICA December 2012 2 Consolidating “Consolidation” Introduction worried that the model was bringing short-term military occupation instead of long-term governance. This report is the result of an attempt to answer By mid-2012, though, the still-relevant question a question that has bedeviled state-building, of military-to-civilian transitions was being eclipsed stabilization, and development efforts in conflict by a more fundamental concern: “Does this concept zones worldwide: “When can the civilians take over?” have a future?” During the year between posing Focusing on recent experiences in Colombia and our initial question and the publication of this comparing what we learned there with the United paper, the Consolidation model and its closest U.S. States’ experiences in post-surge Iraq and especially analogue, the “Stability Operations” component of Afghanistan, WOLA sought to identify the conditions counterinsurgency (COIN), have lost significant that should be in place for civilians to replace military momentum within the Colombian and U.S. leaderships. personnel as quickly as possible in previously The problem has grown so acute that key personnel are ungoverned and conflictive areas. now leaving. This report will lay out some of these conditions. Frustration with both the Colombian and Afghan They include clear criteria for security, as would be models may be justified, as they have been more expected—but security has, in fact, been the easier part.