The Future of US-Colombia Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capitán De Navío Ricardo Alberto Rosero Eraso / 29-121

Informativo virtual Unidos por el mar para integrar la familia y exhaustos por N° 170 naval colombiana www.cyber-corredera.de el último poste Director: Jorge Serpa Erazo • Editor: TFES(r) Francisco Rodríguez Aguilera mailto:[email protected] EN ESTA EDICIÓN: CYBER-ENTREVISTA: CAPITÁN DE NAVÍO RICARDO VELERO DE LA ESCUELA NAVAL OBTIENE PRIMER ALBERTO ROSERO ERASO / 29-121 PUESTO EN REGATAS SABATINAS 2015 LA INFANTERÍA DE MARINA DEL POSCONFLICTO CRISTINA FELFLE, REINA DE LOS MARINOS 45 AÑOS DEL PRIMER AVISTAMIENTO AL INSCRIPCIONES ABIERTAS PARA EL PROGRAMA DE CONTINENTE AUSTRALIANO, POR PARTE DE LA “GRUMETE POR UNA SEMANA” TRIPULACION COLOMBIANA DEL “GLORIA”. ÚLTIMO POSTE: Denuncio a todos mis instructores ASESORES DE GENERAL (R) MORA RENUNCIAN CYBER ZAFARRANCHO GRAFICO Segunda actividad de la Fuerza Naval del Caribe en el CYBER-CORREO DE LA ARC LULU marco del mes de la Mujer: MARINOS FIRMARON PACTO DE RECHAZO A LA VIOLENCIA CONTRA LA CYBER MASCARON DE PROA MUJER CYBER-ENTREVISTA: CAPITÁN DE NAVÍO RICARDO ALBERTO ROSERO ERASO / 29-121 Señor Capitán de Navío Ricardo Alberto Rosero Eraso: ¡Cuéntenos! ¿Cómo fueron sus primeros años, su niñez, adolescencia y cómo estaba conformado su núcleo familiar? Desafortunadamente mi madre murió siendo yo muy niño. Pero tuve muchas mamás: mis cinco tías, mi hermana mayor y mis catorce primas mayores que yo. Fui muy feliz ya que por ser hijo de Oficial del Ejército, viví los continuos traslados de guarnición todos como una aventura; estuve de niño y joven en Pasto, Cali, Barranquilla, Bucaramanga y Tunja. Estudié siempre en colegios de los Padres Jesuitas y tengo muchísimos amigos regados por el país. -

Statement by Thomas W

STATEMENT BY THOMAS W. O’CONNELL ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF DEFENSE FOR SPECIAL OPERATIONS AND LOW INTENSITY CONFLICT BEFORE THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM, UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 108th CONGRESS STATEMENT FOR THE RECORD JUNE 17, 2004 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE COUNTERNARCOTICS IN COLOMBIA Chairman Davis, Representative Waxman, and distinguished members of the Committee, it is my honor to appear before you today to discuss the Department of Defense programs and policy that support for National Drug Control Strategy and to provide a current assessment of this strategy’s effectiveness in Colombia. The Department appreciates that the support Congress provides is critical to our efforts in fighting narcoterrorism in Colombia. DoD’S Role in the National Drug Control Strategy The Office of Counternarcotics is the focal point for DoD’s counterdrug activities, which support the National Drug Control Strategy. The Department’s counternarcotics missions include detection and monitoring, demand reduction, support to domestic and host nation law enforcement and/or military forces. The Department carries out these activities by acting as the lead federal agency to detect and monitor the aerial and maritime transit of illegal drugs toward the United States; collecting, analyzing and disseminating intelligence on drug activity; and providing training for U.S. and foreign drug law enforcement agencies and foreign military forces with drug enforcement responsibilities. In the international arena, the Department of Defense provides much of its counternarcotics support through deployments and programs to train, equip and furnish intelligence and operational support for drug detection, monitoring, and interdiction operations conducted by partner counterdrug forces. -

Colombia=S Killer Networks

COLOMBIA===S KILLER NETWORKS The Military-Paramilitary Partnership and the United States Human Rights Watch/Americas Human Rights Watch Arms Project Human Rights Watch New York AAA Washington AAA London AAA Brussels Copyright 8 November 1996 by Human Rights Watch. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN: 1-56432-203-3 Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number: 96-77749 Human Rights Watch/Americas Human Rights Watch/Americas was established in 1981 to monitor human rights in Latin America and the Caribbean. José Miguel Vivanco is executive director; Anne Manuel is deputy director; James Cavallaro is the Brazil director; Joel Solomon is the research director; Jennifer Bailey, Sebastian Brett, Sarah DeCosse, and Robin Kirk are research associates; Steve Hernández and Paul Paz y Miño are associates. Stephen L. Kass is the chair of the advisory committee; Marina Pinto Kaufman and David E. Nachman are vice chairs. Human Rights Watch Arms Project The Human Rights Watch Arms Project was established in 1992 to monitor and prevent arms transfers to governments or organizations that commit gross violations of internationally recognized human rights and the rules of war and promote freedom of information regarding arms transfers worldwide. Joost R. Hiltermann is the director; Stephen D. Goose is the program director; Zahabia Adalamy, Andrew Cooper, and Ernst Jan Hogendoorn are research assistants; Rebecca Bell is the associate; William M. Arkin, Kathi L. Austin, Ann Peters, Monica Schurtman, and Frank Smyth are consultants. -

The Colombia-US Experience

14 Partnership: The Colombia-U.S. Experience Michael Miklaucic and Juan Carlos Pinzón1 trong security partnerships are not born overnight. They must be built on a foundation of shared goals, mutual respect, and understanding. The Colombia-U.S. Ssecurity partnership is built upon just such a relationship, one that evolved over generations and spans multiple sectors. Although, in common with all Latin American countries, Colombia’s historical and cultural roots can be traced to the Iberian colonization of the Western Hemisphere, trade, diplomatic, and military relations with the United States date back to the early 19th century. The United States was among the first countries to recognize Colombia when it declared independence from Spain, receiving a diplomatic representative in Washington in 1822 and establishing its first diplomatic mission in Cartagena and Santa Marta in 1823. The first commercial treaty between the two young countries was signed in 1824, followed by a treaty of friendship and commerce in 1848.2 The Colombia-U.S. relationship has not been without its ups and downs historically, but it has led to familiarity, and in recent years a common understanding of shared security challenges in the Western Hemisphere. This chapter describes the context, as well as the richness, of a partnership based on shared goals, demonstrable commitment to those goals, mutual respect, trust, and consultation. While Plan Colombia, a Colombia-U.S. initiative targeting security issues and drug-trafficking, was a historic and epic phase of the Colombia-U.S. partnership, much has been written on it, and therefore it is not the focus of this chapter. -

2019 Informe De Gestión 2015

FUERZAS MILITARES DE COLOMBIA ARMADA NACIONAL INFORME DE GESTIÓN 2015 - 2018 ARMADA NACIONAL 2019 FUERZAS MILITARES DE COLOMBIA ARMADA NACIONAL INFORME DE GESTIÓN 2015 - 2018 INFORME DE GESTIÓN ARC 2015 - 2018 - 2018 ARC 2015 DE GESTIÓN INFORME ARMADA NACIONAL 2019 3 Contenido 1. PRESENTACIÓN 2. INTRODUCCIÓN 3. ACTIVIDADES MISIONALES DE LA INSTITUCIÓN 3.1. Defensa y Seguridad Nacional 3.1.1. Mantener la integridad territorial 3.1.2. Combate al terrorismo y Grupos Armados Organizados (GAO) 3.1.3. Seguridad de la población y protección de la infraestructura marítima 3.1.4. Acción Integral 3.1.5. Desminado Humanitario 3.1.6. Capacidades aeronavales de vigilancia marítima 3.1.7. Fuerzas Especiales Navales 3.2. Seguridad Integral Marítima y Fluvial 3.2.1. Combate al Narcotráfico 3.2.2. Búsqueda y Rescate (BYR) 3.2.3. Capacidades Operacionales de Guardacostas 3.3. Rol Internacional 3.3.1. Operaciones Internacionales 3.3.2. Asistencia Humanitaria INFORME DE GESTIÓN ARC 2015 - 2018 - 2018 ARC 2015 DE GESTIÓN INFORME 3.3.3. Operaciones de Paz 3.3.4. Diplomacia Naval 3.4. Protección de Medio Ambiente y Manejo de Desastres Naturales 3.4.1. Protección Medio Ambiente 3.4.2. Manejo de Desastres Naturales 3.5. Mando, Control y Comunicaciones 3.5.1. Gestión Comunicaciones 3.5.2. Relacionamiento con líderes de opinión 3.5.3. Atención al Ciudadano 3.5.4. Perfil de Imagen de la Armada de Colombia 3.5.5. Transparencia y Anticorrupción 3.5.6. Inteligencia y Contrainteligencia 4 4. DIRECCIONAMIENTO ESTRATÉGICO Y ESTRUCTURA DE FUERZA 4.1. Capacidades Operacionales 4.1.1. -

Testimony of General James T. Hill United States Army Commander United States Southern Command

file:///C|/andeansecbook/04-03-24hill.htm TESTIMONY OF GENERAL JAMES T. HILL UNITED STATES ARMY COMMANDER UNITED STATES SOUTHERN COMMAND BEFORE THE HOUSE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES March 24, 2004 Introduction Mr. Chairman, Representative Skelton, Members of the Committee, it is my privilege to present the posture statement of the United States Southern Command. The men and women of our command are making enormous contributions to the War on Terrorism and the defense of this country on a daily basis. Your Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, Marines, Coast Guardsmen, and Department of Defense civilians are working throughout the region to promote U.S. national security interests. Their work has done much to preserve stability and strengthen relationships with our allies. Simultaneously we are building a cooperative security community that will advance security and stability in the generation to come. The security picture in Latin America and the Caribbean has grown more complex over the past year. Colombia’s considerable progress in the battle against narcoterrorism is offset by negative developments elsewhere in the region, particularly in Haiti, Bolivia, and Venezuela. These developments represent an increasing threat to U.S. interests. We face two primary types of threats in the region: an established set of threats detailed in previous years and a nascent set likely to raise serious issues during this year. On the traditional front, we still face threats from narcoterrorists and their ilk, a growing threat to law and order in partner nations from urban gangs and other illegal armed groups, which are also generally tied to the narcotics trade, and a lesser but sophisticated threat from Islamic radical groups in the region. -

Colombia Ivory Liberia Coast Nigeria Ecuador

CANADA U. S. A. PORTUGAL MOROCCO ATLANTIC MEXICO OCEAN CUBA WESTERN SAHARA ALGERIA BELIZE HONDURAS MAURITANIA GUATEMALA NICARAGUA EL SALVADOR MALI GAMBIA COSTA RICA VENEZUELA GUYANA GUINEA BISSAU PANAMA FRENCH GUIANA GUINEA NIGER SURINAME SIERRA LEONE COLOMBIA IVORY LIBERIA COAST NIGERIA ECUADOR BRAZIL PACIFIC GABON PERU OCEAN CONGO Colombia BOLIVIA PARAGUAY ANGOLA CHILE NAMIBIA URUGUAY ARGENTINA SOUTH AFRICA by Kenneth Finlayson This special campaign issue of Veritas is devoted in Latin America. The more than fifty years of Ameri- to Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) in Colom- can military professional exchanges and the increased bia. The nation of Colombia has a unique and long-stand- numbers of such exchanges are indicative of Colombia’s ing relationship with the United States dating from the importance to U.S. strategic interests in Latin America. Korean War. Today, both nations are united in an effort The commander of the U.S. Army Special Warfare to counter the problem of narco-terrorism as part of Center, Brigadier General William P. Yarborough, vis- America’s Global War on Terrorism. The purpose of this ited Colombia and provided recommendations that were issue is to present the historical background of that long- incorporated in Plan Lazo (lasso) designed to eliminate term relationship, describe the Colombian military and the violence caused by bandits and quasi-guerrillas in police forces and their overseas experiences, provide an the countryside. The recurrent themes espoused in Plan overview of the U.S. military commitment in Colombia, Lazo are still relevant and are important to understand explain what ARSOF soldiers are doing in Colombia, Colombia today. -

Country Reports on Terrorism 2012 (PDF)

Country Reports on Terrorism 2012 May 2013 ________________________________ United States Department of State Publication Bureau of Counterterrorism Released May 2013 Country Reports on Terrorism 2012 is submitted in compliance with Title 22 of the United States Code, Section 2656f (the “Act”), which requires the Department of State to provide to Congress a full and complete annual report on terrorism for those countries and groups meeting the criteria of the Act. COUNTRY REPORTS ON TERRORISM 2012 Table of Contents Chapter 1. Strategic Assessment Chapter 2. Country Reports Africa Overview, Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership, The Partnership for East African Regional Counterterrorism, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda East Asia and Pacific Overview, China (Hong Kong and Macau), Indonesia, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Republic of Korea, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand Europe Overview, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Denmark, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Kosovo, The Netherlands, Norway, Russia, Serbia, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, United Kingdom (Northern Ireland) Middle East and North Africa Overview, Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Israel (West Bank and Gaza), Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen South and Central Asia Overview, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan Western Hemisphere Overview, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Venezuela Chapter 3. State Sponsors of Terrorism Overview Cuba, Iran, Sudan, Syria Chapter 4. The Global Challenge of Chemical, Biological, Radiological, or Nuclear (CBRN) Terrorism 2 Chapter 5. -

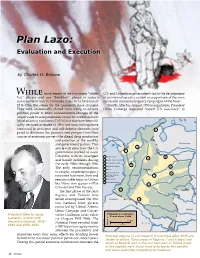

Plan Lazo: Evaluation and Execution

Plan Lazo: Evaluation and Execution by Charles H. Briscoe While involvement of the two major “white- U.S. and Colombian governments led to the development hat” players and one “black-hat” player in today’s of an internal security system to support one of the most narco-terrorist war in Colombia dates to La Violencia of successful counterinsurgency campaigns of the time.1 1948–1966, the stakes for the insurgents have changed. Shortly after his August 1958 inauguration, President They have dramatically shifted from trying to achieve Lleras Camargo requested “expert U.S. assistance” to political power to effect socioeconomic changes in the countryside to using economic power to control sociopo- litical affairs in rural areas.La Violencia may have been offi- cially declared as ended in 1966, but mass killings have continued as insurgent and self-defense elements com- 3 peted to dominate the peasants and prosper from their source of economic power—the illegal drug production and extortion of the wealthy Panama and government justices. This Venezuela article will show how the U.S. 2 government worked to assist 1 Colombia with its insurgent 1 Urabá-Darien 6 4 and bandit problems during 2 Caribe-Since-San Jorge 3 Serranía del Perijá the early 1960s through 1966. 5 4 Magdalena Medio 8 The early recommendations 5 Pacific Bogotá to employ counterinsurgency 6 Saravena-Arauca 8 Andean Orinoco Colombia measures had merit then and 7 Piedmont 7 remain viable today in Colom- 8 Ariarí-Meta 9 Caquetá-Putumayo bia. Many now appear in Plan 8 Colombia and Plan Patriota. -

U.S Policy Regarding Narcotics Control in Colombia Hearing Caucus on International Narcotics Control United States Senate

S. HRG. 108–236 U.S POLICY REGARDING NARCOTICS CONTROL IN COLOMBIA HEARING BEFORE THE CAUCUS ON INTERNATIONAL NARCOTICS CONTROL UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 3, 2003 Printed for the use of the Committee on Narcotics ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 87–649 PDF WASHINGTON : 2004 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 03-FEB-2003 11:09 Jan 14, 2004 Jkt 087649 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 D:\NARC\87649.TXT SSC2 PsN: SSC2 SENATE CAUCUS ON INTERNATIONAL NARCOTICS CONTROL IN COLOMBIA ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION Charles E. Grassley, Iowa, Chairman Joseph R. Biden, Delaware, Co-Chair JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama BOB GRAHAM, Florida MIKE DeWINE, Ohio DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California NORM COLEMAN, Minnesota ERIC J. AKERS, Staff Director MARCIA LEE, Minority Staff Director (II) VerDate 03-FEB-2003 11:09 Jan 14, 2004 Jkt 087649 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 D:\NARC\87649.TXT SSC2 PsN: SSC2 C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on June 3, 2003 ................................................................................. 1 STATEMENTS Grassley, Hon. Charles E., U.S. Senator from Iowa ............................................. 1 Biden, Hon. Joseph R., U.S. Senator from Delaware, prepared statement ........ 1 DeWine, Hon. Mike, U.S. Senator from Ohio ........................................................ 3 Sessions, Hon. Jeff, U.S. Senator from Alabama .................................................. 43 WITNESSES Santos-Calderon, Hon. Francisco, Vice President, Republic of Colombia, Bogota´, Colombia ................................................................................................. -

2016 Delgado Jorge Eduardo 1041615 Ethesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ COUNTER-INSURGENCY IN COLOMBIA THE ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION OF A MILITARY STRATEGIC TRADITION Delgado, Jorge Eduardo Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 COUNTER-INSURGENCY IN COLOMBIA: THE ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION OF A MILITARY STRATEGIC TRADITION By Jorge Eduardo Delgado Supervised by Professor Michael Rainsborough A thesis presented for the degree of Department of War Studies Doctor of Philosophy in War Studies King’s College London May 2016 1 ABSTRACT This research proposes to examine the composition and evolution of the Colombian military’s approach to counter-insurgency since the origins of the internal armed conflict that affects the country. -

MICROCOMP Output File

S. HRG. 108–440, PT. 5 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION FOR APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2005 HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON S. 2400 TO AUTHORIZE APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2005 FOR MILITARY ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE, FOR MILITARY CON- STRUCTION, AND FOR DEFENSE ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY, TO PRESCRIBE PERSONNEL STRENGTHS FOR SUCH FISCAL YEAR FOR THE ARMED FORCES, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES PART 5 EMERGING THREATS AND CAPABILITIES MARCH 3, 10; APRIL 2, 2004 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services VerDate 11-SEP-98 14:36 Feb 23, 2005 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 93575.CON SARMSER2 PsN: SARMSER2 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION FOR APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2005—Part 5 EMERGING THREATS AND CAPABILITIES VerDate 11-SEP-98 14:36 Feb 23, 2005 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 93575.CON SARMSER2 PsN: SARMSER2 S. HRG. 108–440, PT. 5 DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE AUTHORIZATION FOR APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2005 HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON S. 2400 TO AUTHORIZE APPROPRIATIONS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2005 FOR MILITARY ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE, FOR MILITARY CON- STRUCTION, AND FOR DEFENSE ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY, TO PRESCRIBE PERSONNEL STRENGTHS FOR SUCH FISCAL YEAR FOR THE ARMED FORCES, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES PART 5 EMERGING THREATS AND CAPABILITIES MARCH 3, 10; APRIL 2, 2004 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services U.S.