UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

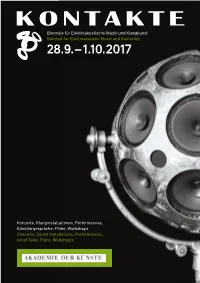

Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops

Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art 28.9. – 1.10.2017 Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops 1 KONTAKTE’17 28.9.–1.10.2017 Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops KONTAKTE '17 INHALT 28. September bis 1. Oktober 2017 Akademie der Künste, Berlin Programmübersicht 9 Ein Festival des Studios für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste A festival presented by the Studio for Electro acoustic Music of the Akademie der Künste Konzerte 10 Im Zusammenarbeit mit In collaboration with Installationen 48 Deutsche Gesellschaft für Elektroakustische Musik Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD Forum 58 Universität der Künste Berlin Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin Technische Universität Berlin Ausstellung 62 Klangzeitort Helmholtz Zentrum Berlin Workshop 64 Ensemble ascolta Musik der Jahrhunderte, Stuttgart Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik der Kunstuniversität Graz Laboratorio Nacional de Música Electroacústica Biografien 66 de Cuba singuhr – projekte Partner 88 Heroines of Sound Lebenshilfe Berlin Deutschlandfunk Kultur Lageplan 92 France Culture Karten, Information 94 Studio für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste Hanseatenweg 10, 10557 Berlin Fon: +49 (0) 30 200572236 www.adk.de/sem EMail: [email protected] KONTAKTE ’17 www.adk.de/kontakte17 #kontakte17 KONTAKTE’17 Die zwei Jahre, die seit der ersten Ausgabe von KONTAKTE im Jahr 2015 vergangen sind, waren für das Studio für Elektroakustische Musik eine ereignisreiche Zeit. Mitte 2015 erhielt das Studio eine großzügige Sachspende ausgesonderter Studiotechnik der Deut schen Telekom, die nach entsprechenden Planungs und Wartungsarbeiten seit 2016 neue Produktionsmöglichkeiten eröffnet. -

Delia Derbyshire

www.delia-derbyshire.org Delia Derbyshire Delia Derbyshire was born in Coventry, England, in 1937. Educated at Coventry Grammar School and Girton College, Cambridge, where she was awarded a degree in mathematics and music. In 1959, on approaching Decca records, Delia was told that the company DID NOT employ women in their recording studios, so she went to work for the UN in Geneva before returning to London to work for music publishers Boosey & Hawkes. In 1960 Delia joined the BBC as a trainee studio manager. She excelled in this field, but when it became apparent that the fledgling Radiophonic Workshop was under the same operational umbrella, she asked for an attachment there - an unheard of request, but one which was, nonetheless, granted. Delia remained 'temporarily attached' for years, regularly deputising for the Head, and influencing many of her trainee colleagues. To begin with Delia thought she had found her own private paradise where she could combine her interests in the theory and perception of sound; modes and tunings, and the communication of moods using purely electronic sources. Within a matter of months she had created her recording of Ron Grainer's Doctor Who theme, one of the most famous and instantly recognisable TV themes ever. On first hearing it Grainer was tickled pink: "Did I really write this?" he asked. "Most of it," replied Derbyshire. Thus began what is still referred to as the Golden Age of the Radiophonic Workshop. Initially set up as a service department for Radio Drama, it had always been run by someone with a drama background. -

John Lennon from ‘Imagine’ to Martyrdom Paul Mccartney Wings – Band on the Run George Harrison All Things Must Pass Ringo Starr the Boogaloo Beatle

THE YEARS 1970 -19 8 0 John Lennon From ‘Imagine’ to martyrdom Paul McCartney Wings – band on the run George Harrison All things must pass Ringo Starr The boogaloo Beatle The genuine article VOLUME 2 ISSUE 3 UK £5.99 Packed with classic interviews, reviews and photos from the archives of NME and Melody Maker www.jackdaniels.com ©2005 Jack Daniel’s. All Rights Reserved. JACK DANIEL’S and OLD NO. 7 are registered trademarks. A fine sippin’ whiskey is best enjoyed responsibly. by Billy Preston t’s hard to believe it’s been over sent word for me to come by, we got to – all I remember was we had a groove going and 40 years since I fi rst met The jamming and one thing led to another and someone said “take a solo”, then when the album Beatles in Hamburg in 1962. I ended up recording in the studio with came out my name was there on the song. Plenty I arrived to do a two-week them. The press called me the Fifth Beatle of other musicians worked with them at that time, residency at the Star Club with but I was just really happy to be there. people like Eric Clapton, but they chose to give me Little Richard. He was a hero of theirs Things were hard for them then, Brian a credit for which I’m very grateful. so they were in awe and I think they had died and there was a lot of politics I ended up signing to Apple and making were impressed with me too because and money hassles with Apple, but we a couple of albums with them and in turn had I was only 16 and holding down a job got on personality-wise and they grew to the opportunity to work on their solo albums. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2017). Michael Finnissy - The Piano Music (10 and 11) - Brochure from Conference 'Bright Futures, Dark Pasts'. This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17523/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] BRIGHT FUTURES, DARK PASTS Michael Finnissy at 70 Conference at City, University of London January 19th-20th 2017 Bright Futures, Dark Pasts Michael Finnissy at 70 After over twenty-five years sustained engagement with the music of Michael Finnissy, it is my great pleasure finally to be able to convene a conference on his work. This event should help to stimulate active dialogue between composers, performers and musicologists with an interest in Finnissy’s work, all from distinct perspectives. It is almost twenty years since the publication of Uncommon Ground: The Music of Michael Finnissy (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998). -

Gardner • Even Orpheus Needs a Synthi Edit No Proof

James Gardner Even Orpheus Needs a Synthi Since his return to active service a few years ago1, Peter Zinovieff has appeared quite frequently in interviews in the mainstream press and online outlets2 talking not only about his recent sonic art projects but also about the work he did in the 1960s and 70s at his own pioneering computer electronic music studio in Putney. And no such interview would be complete without referring to EMS, the synthesiser company he co-founded in 1969, or namechecking the many rock celebrities who used its products, such as the VCS3 and Synthi AKS synthesisers. Before this Indian summer (he is now 82) there had been a gap of some 30 years in his compositional activity since the demise of his studio. I say ‘compositional’ activity, but in the 60s and 70s he saw himself as more animateur than composer and it is perhaps in that capacity that his unique contribution to British electronic music during those two decades is best understood. In this article I will discuss just some of the work that was done at Zinovieff’s studio during its relatively brief existence and consider two recent contributions to the documentation and contextualization of that work: Tom Hall’s chapter3 on Harrison Birtwistle’s electronic music collaborations with Zinovieff; and the double CD Electronic Calendar: The EMS Tapes,4 which presents a substantial sampling of the studio’s output between 1966 and 1979. Electronic Calendar, a handsome package to be sure, consists of two CDs and a lavishly-illustrated booklet with lengthy texts. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 12 AUGUST 1ST, 2016 August 1, 2016 Up the Ladder INCOMING LETTERS Written by Paul McGowan I am responding to the recent article on DACs and the quick brush-off of ladder DACs. (Richard Murison’s “My Kingdom for a DAC”, Richard didn’t brush off ladder DACs so much as say that they were damned hard to build properly --Ed.) There are several R2R or ladder DACs on the market and in my opinion and that of many others they are far superior to any delta-sigma DAC on the market. The best example is the Audio-GD Master 7 dac. Also, the great Audio Note DACs are ladder DACs. These DACs have a musicallity that delta- sigma DACs dream about. Delta-sigma dacs are used mostly because R2R chips are simply too difficult and expensive to make.The old R2R chips are expensive, hard to find and no longer in production. I believe Mytek is making an R2R chip and Audio Note has one in development. Did a recent comparison of my Master 7 with a friend’s DCS stack and even he thought the Master 7 was better. The DCS is 10 times the price. Yes, a ladder DAC will not do DSD, but for me that is no great loss. Alan Hendler Doesn't Like Tchaikovsky Either Three cheers for Mr. Schenbeck. He writes concisely and entertainingly and, with his adroit embedding of musical examples, uses the electronic magazine format as it should be used. I look forward to each of his contributions. Never much liked Tchaikovsky either. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Microsoft Outlook

Dave M. Peck From: Squidco <[email protected]> Sent: Thursday, September 14, 2017 10:11 AM To: Dave M. Peck Subject: SQUIDCO Email Update September 14, 2017 UPDATE September 14, 2017 We wanted to make a new art— new expressions of art— in an art world that was, for us, traditional." —Herman Nitsch Essential Labels Alga Marghen KARLRECORDS Art Yard Matchless Clang Mikroton Recordings Confront Room40 Creative Sources Someone Good / Room40 Discus Taping Policies Evil Clown Trost Records Fragment Factory Wide Hive Holidays Records Creative Artists 1 • Abecassis, Eryck / Francisco Meirino • Derek Bailey / Mick Beck / Paul Hession • Borbetomagus • Tony Buck • Deep Tide Quartet (Archer / Macari / Cole / Shaw) • The Elks (Fagaschinski/Allbee/Roisz/Zapparoli) • Georg Graewe / Mark Sanders • Haco • Junk & The Beast (Petr Vrba / Veronika Mayer) • Alice Kemp • Leap of Faith • Kurt Liedwart • Roscoe Mitchell • Dafna Naphtali / Gordon Beeferman • Hermann Nitsch • Orfeo 5 (Blezard/Bourne/Jafrate w/ Prince/Oliver/Kane) • Charlemagne Palestine • Pat Patrick And The Baritone Saxophone Retinue • Massimo Pupillo / Alexandre Babel / Caspar Brotzmann • Ernesto Rodrigues / Ulrike Brand / Olaf Rupp • Sakata / Mota / Di Domenico / Calleja • Udo Schindler • String Theory [Boston, USA] • String Theory [PORTUGAL] • Eckard Vossas 4 (Vossas / Fields / Henkel / Nabatov) • Christian Wolfarth / Jason Kahn • Christian Wolff / Eddie Prevost • Nate Wooley / Daniele Martini / Joao Lobo • Zeitkratzer / Svetlana Spajic/Dragana Tomic/Obrad Milic • Zeitkratzer + Elliott Sharp Jazz & Improvisation Bailey, Derek / Mick Beck / Paul Hession: Meanwhile, Back In Sheffield... (Discus) Free improvising guitar legend Derek Bailey was invited to perform in his home town of Sheffield, England in 2004 with the trio of Mick Beck on tenor sax, bassoon, and whistles, and Paul Hession on drums, Bailey's first visit in many years, and a joyful occasion as the collective group explores a wide range of approaches to creating instant compositions. -

Für Sonntag, 21

GEORGE HARRISON-Box THE APPLE YEARS Um zu bestellen, einfach Abbildung anklicken Abbildungen: Box; Kollage mit Box, Booklet und CDs. Freitag, 19. September 2014: Box (7 CDs & 1 DVD) GEORGE HARRISON - THE APPLE YEARS. 84,90 € inkl. Versand und gut verpackt Inhalt der Box: CD WONDERWALL MUSIC, CD ELECTRONIC SOUND, Doppel-CD ALL THINGS MUST PASS, CD LIVING IN THE MATERIAL WORLD, CD DARK HORSE, CD EXTRA TEXTURE (READ ALL ABOUT IT), DVD, Booklet. Die CDs sind auch einzeln erhältlich jeweils mit den 20-Seiten-Booklet. Die DVD und das zusätzliche Büchlein gibt es nicht einzeln sondern nur in der Box. Freitag, 19. September 2014: CD (remastert) mit 20-Seiten-Booklet WONDERWALL MUSIC BY GEORGE HARRISON. Apple / Universal, Europa. Freitag, 1. November 1968: Vinyl-LP WONDERWALL MUSIC BY GEORGE HARRISON. Apple TCSAPCOR 1 (geplant STAP 1), Großbritannien. *Dezember 1967: EMI Abbey Road Studios, London, Großbritannien und **Dienstag, 9. - Montag, 15. Januar 1968: EMI Recording Studios, Universal Insurance Building, Phirozeshah Mehta Road, Fort, Bombay 400001, Indien: Track 1: Microbes (George Harrison) (3:39). Track 2: Red Lady Too (George Harrison) (1:53). Track 3: Table And Pakavaj (George Harrison) (1:04). Track 4: In The Park (George Harrison) (4:08). Track 5: Drilling A Home (George Harrison) (3:07). Track 6: Guru Vandana (George Harrison) (1:04). Track 7: Greasy Legs (George Harrison) (1:27). Track 8: Ski-ing And Gat Kirwani (George Harrison) (3:06). Track 9: Dream Scene (George Harrison) (5:27). Track 10: Party Seacombe (George Harrison) (4:34): Track 11: Love Scene (George Harrison) (4:16). Track 12: Crying (George Harrison) (1:14). -

Immersion Into Noise

Immersion Into Noise Critical Climate Change Series Editors: Tom Cohen and Claire Colebrook The era of climate change involves the mutation of systems beyond 20th century anthropomorphic models and has stood, until recent- ly, outside representation or address. Understood in a broad and critical sense, climate change concerns material agencies that im- pact on biomass and energy, erased borders and microbial inven- tion, geological and nanographic time, and extinction events. The possibility of extinction has always been a latent figure in textual production and archives; but the current sense of depletion, decay, mutation and exhaustion calls for new modes of address, new styles of publishing and authoring, and new formats and speeds of distri- bution. As the pressures and re-alignments of this re-arrangement occur, so must the critical languages and conceptual templates, po- litical premises and definitions of ‘life.’ There is a particular need to publish in timely fashion experimental monographs that redefine the boundaries of disciplinary fields, rhetorical invasions, the in- terface of conceptual and scientific languages, and geomorphic and geopolitical interventions. Critical Climate Change is oriented, in this general manner, toward the epistemo-political mutations that correspond to the temporalities of terrestrial mutation. Immersion Into Noise Joseph Nechvatal OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS An imprint of MPublishing – University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, 2011 First edition published by Open Humanities Press 2011 Freely available online at http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.9618970.0001.001 Copyright © 2011 Joseph Nechvatal This is an open access book, licensed under the Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. Under this license, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy this book so long as the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or similar license. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums.