Psaudio Copper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SENATE JOINT RESOLUTION 803 By

SENATE JOINT RESOLUTION 803 By Henry A RESOLUTION to honor the memory of Earl Scruggs, an American musical treasure. WHEREAS, the members of this General Assembly and music fans around the globe were greatly saddened to learn of the passing of bluegrass music legend and American treasure, Mr. Earl Scruggs; and WHEREAS, Earl Scruggs was revered around the world as a musical genius whose innovative talent on the five-string banjo pioneered modern banjo playing and he crafted the sound we know as bluegrass music. We will never see his superior; and WHEREAS, born on January 6, 1924, in Flint Hill, North Carolina, Earl Eugene Scruggs was the son of George Elam Scruggs, a farmer and bookkeeper who played the banjo and fiddle, and Lula Ruppe Scruggs, who played the pump organ in church; and WHEREAS, after losing his father at the age of four, Earl Scruggs began playing banjo and guitar at a very young age, using the two-finger picking style on the banjo until he was about ten years old, when he began to use three - the thumb, index, and middle finger - in an innovative up-picking style that would become world-renowned and win international acclaim; and WHEREAS, as a young man, Mr. Scruggs' banjo mastery led him to play area dances and radio shows with various bands, including Lost John Miller and His Allied Kentuckians. In December of 1945, he quit high school and joined Bill Monroe's band, the Blue Grass Boys; and WHEREAS, with his magnificent banjo picking, the group's popularity soared and Earl Scruggs redefined the sound of bluegrass music, as evidenced on such classic Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys tracks as "Blue Moon of Kentucky," "Blue Grass Breakdown," and "Molly and Tenbrooks (The Race Horse Song)"; and WHEREAS, with his mastery of the banjo and guitar matched only by his beautiful baritone, Mr. -

Course Description, Class Outline and Syllabus Instructor: Peter Elman

Course description, class outline and syllabus Instructor: Peter Elman Title: “A Round-Trip Road Trip of Country Music, 1950-present: From Nashville to California to Texas--and back.” Course Description: An up close and personal look at the golden era of American country music, this class will explore key movements that contributed to the explosive growth of country music as an industry, art form and subculture. The first half of this course will focus on three major regions: Nashville, California and Texas, and concentrate on the period 1950-1975. The second half will look at the women of country, discuss the making of a country song and record, look at the work of five great songsmiths, visit the country music of the 1980’s, and end with an examination of Americana music. The course will do this through lectures, photographs, recorded music, film clips, question and answer sessions, and the use of live music. The instructor will play piano, guitar and sing, and will choose appropriate examples from each region, period and style. - - - - - - - - - - - Course outline by week, with syllabus; suggested reading, listening and viewing Week one: The rise of “honky-tonk” music, 1940-60: Up from bluegrass—the roots of country music. Roy Acuff, Ernest Tubb, Hank Williams, Kitty Wells, Lefty Frizzell, Porter Wagoner, Jim Reeves, Webb Pierce, Ray Price, Hank Lochlin, Hank Snow, and the Grand Old Opry. Reading: The Nashville sound: bright lights and country music Paul Hemphill, 1970-- the definitive portrait of the roots of country music. Listening: 20 of Hank Williams Greatest Hits, Mercury, 1997 30 #1 Country Hits of the 1950s, 3-disc set, Direct Source, 1997 Viewing: O Brother Where Art Thou, 2000, by the Coen brothers America's Music: The Roots of Country 1996, three-part, six episode documentary. -

41 Kult NT.Qxp

DAGSAVISEN NYE TAKTERKULTUR TIRSDAG 18. OKTOBER 2005 41 Sylvians fire årtier 70-TALLET Danner bandet Japan i 1974 sammen med broren Steve og skifter navn fra Norge David Batt til David Sylvian. Blir oppdaget av den senere så beryktede manageren Simon Napier-Bell (Wham m.m.). Gir ut to lite vellykkede glam-rock-pregede album, men tittelkuttet på tredjeplata «Quiet Life» (1979) peker mot noe mer sofistikert og særpreget. 80-TALLET Med platene «Gentlemen Take Polaroids» (1980) og «Tin Drum» (1981) utvikler Japan en egenartet asia- tiskinspirert sound, og får en hit med den minimalis- tiske balladen «Ghosts». Oppløses i 1982 etter mye intern krangel. Sylvian begynner å samarbeide med eksperimentelle musikere som Riuichi Sakamoto, Robert Fripp (King Crimson) og Holger Czukay (Can). Gir ut sitt første soloalbum «Brilliant Trees» (1984), følger opp med doble «Gone To Earth» (1986) og «Secrets Of The Beehive» (1987), som alle har status som kultklassikere. Jobber også innen teater, foto- kunst og dans. 90-TALLET Japan gjenforenes under navnet Rain Tree Crow, lager et halvbra album og oppløses igjen. Sylvian flytter til USA og gifter seg med Prince-protesje- en Ingrid Chavez. Lager en del instrumental ambient- musikk, gjenopptar sam- arbeidet med Robert Fripp på duoalbumene «The First Day» (1993) og FOTO: KEVIN WESTERBERG/DOT «Redemption» (1994), som ikke hører til hans sterkeste. Gir ut sitt første viteten. Jeg følte at jeg var i ferd med å bli kvalt av tenkt å gå tilbake til å lage tradisjonelle låter igjen. soloalbum siden 1987, min egen historie. Det var svært frigjørende å bli fer- Nine Horses-plata er ikke nødvendigvis en indika- «Dead Bees On A Cake» dig med kontrakten og bygge mitt eget studio. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

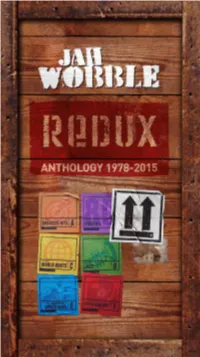

View the Redux Book Here

1 Photo: Alex Hurst REDUX This Redux box set is on the 30 Hertz Records label, which I started in 1997. Many of the tracks on this box set originated on 30 Hertz. I did have a label in the early eighties called Lago, on which I released some of my first solo records. These were re-released on 30 Hertz Records in the early noughties. 30 Hertz Records was formed in order to give me a refuge away from the vagaries of corporate record companies. It was one of the wisest things I have ever done. It meant that, within reason, I could commission myself to make whatever sort of record took my fancy. For a prolific artist such as myself, it was a perfect situation. No major record company would have allowed me to have released as many albums as I have. At the time I formed the label, it was still a very rigid business; you released one album every few years and ‘toured it’ in the hope that it became a blockbuster. On the other hand, my attitude was more similar to most painters or other visual artists. I always have one or two records on the go in the same way they always have one or two paintings in progress. My feeling has always been to let the music come, document it by releasing it then let the world catch up in its own time. Hopefully, my new partnership with Cherry Red means that Redux signifies a new beginning as well as documenting the past. -

What You No. .John Hartford, with Benny Martin, David Briggs, Sam Bush, Et Al

NJ,)~ Knows- What You no. .John Hartford, with Benny Martin, David Briggs, Sam Bush, et al. 12 selections, vocal and instrumental, stereo. Flying Fish 028, 3320 Halstad St., Chicago, Ill. 60657, 1976. Reviewed by Bob Blackman About the best thing that can be said for Nobody Knows What You Do is that it's a slight improvement over John Hartford's previous record, Mark Twang (reviewed in Folklore Forum 10 Gpring)1977; 10:l). This is due not to Hartford but entirely to the welcome addition of some fine sidemen (absent on the earlier release). Their hot picking compensates for the further deterioration of Hartford's songwriting. Hartford's sense of humor, always his strongest point, has become plain silly. Lyrics like "The Golden Globe Award" (singing the praises of his girl's "golden globes") and "Granny Won'tcha Smoke Some Marijuana" are at a high school level of self-conscious sniggering. "The False Hearted Tenor Waltz" expresses his desire to sing that high lonesome bluegrass tenor, and would be one of the record's more successful cuts if Hartford's "comic" falsetto weren't so grating. The title song is so completely pointless that it's hard to understand why anyone would bother to write it, let alone record it. The one serious song is "In Tall Buildings," another in a long line of "Oh, life in the city is such a drag" compositions that are churned out by every songwriter in the business. The lyrics here are as trite as most such songs, but at least it's nice to hear one track sung "straight." Most of the other so-called songs are just words thrown together between long instrumental breaks. -

Still on the Road Session Pages: 1970

STILL ON THE ROAD 1970 RECORDING SESSIONS MARCH 3 New York City, New York Studio B, Columbia Recording Studios, 5th Self Portrait session 4 New York City, New York Studio B, Columbia Recording Studios, 4th Self Portrait session 5 New York City, New York Studio B, Columbia Recording Studios, 6th Self Portrait session 11 Nashville, Tennessee Columbia Music Row Studios, 1st Self Portrait overdub session 12 Nashville, Tennessee Columbia Music Row Studios, 2nd Self Portrait overdub session 13 Nashville, Tennessee Columbia Music Row Studios, 3rd Self Portrait overdub session 17 Nashville, Tennessee Columbia Music Row Studios, 4th Self Portrait overdub session 26, 27 Los Angeles, California Columbia Studio B, Hollywood, 5th Self Portrait overdub session 30 Nashville, Tennessee Columbia Music Row Studios, 6th Self Portrait overdub session APRIL 2 Nashville, Tennessee Columbia Music Row Studios, 7th Self Portrait overdub session 3 Nashville, Tennessee Columbia Music Row Studios, 8th and last Self Portrait overdub session MAY 1 New York City, New York Columbia Studio B, 1st New Morning session 17 Carmel, New York The Home Of Thomas B. Allen, Earl Scruggs Documentary JUNE 1 New York City, New York Columbia Studio E, 2nd New Morning session 2 New York City, New York Columbia Studio E, 3rd New Morning session 3 New York City, New York Columbia Studio E, 4th New Morning session 4 New York City, New York Columbia Studio E, 5th New Morning session 5 New York City, New York Columbia Studio E, 6th New Morning session 30 New York City, New York Columbia Studio E, 7th New Morning session JULY 13 New York City, New York Columbia Studio E, 1st New Morning overdub session 23 Nashville, Tennessee Columbia Studio E, 2nd New Morning overdub session AUGUST 12 New York City, New York Columbia Studio E, 8th and last New Morning session Still On The Road: Bob Dylan recording sessions 1970 1790 Studio B Columbia Recording Studios New York City, New York 3 March 1970 4th Self Portrait recording session, produced by Bob Johnston. -

University of Southampton Research Repository

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES English GUILT & The Storyteller and the Truth by Florentia Antoniou Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2017 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES English Doctor of Philosophy GUILT & The Storyteller and the Truth by Florentia Antoniou Guilt is a historical novel set in the second half of the twentieth century (1963 – 1975) in the Mediterranean island of Cyprus. The story begins three years after the island was granted its independence from the British, when intense intercommunal violence between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots was on the rise, and ends several months after the Turkish invasion in the summer of 1974. Guilt follows the life of a Greek Cypriot from her childhood to her adulthood, depicting the difficulty of growing up during politically troubled times as well as the life of women in the seventies in Cyprus. -

John Hartford Aereo-Plain Mp3, Flac, Wma

John Hartford Aereo-Plain mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Aereo-Plain Country: US Released: 1971 Style: Bluegrass, Country, Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1101 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1158 mb WMA version RAR size: 1749 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 980 Other Formats: MP2 VQF DMF AA VOX ASF DTS Tracklist Hide Credits Turn Your Radio On A1 Guitar – Norman Blake Vocals – John Hartford, Norman Blake , Tut Taylor, Vassar 1:17 ClementsWritten-By – Albert E. Brumley Steamboat Whistle Blues A2 Banjo – John HartfordBass – Randy ScruggsDobro – Tut TaylorFiddle – Vassar 3:23 ClementsGuitar – Norman Blake Vocals – John HartfordWritten-By – John Hartford Back In The Goodle Days A3 Banjo – John*Bass – Randy*Dobro – Tut*Fiddle – Vassar*Guitar – Norman*Vocals – 3:38 John*Written-By – John Hartford Up On The Hill Where They Do The Boogie A4 2:40 Bass – Randy*Guitar – John*Mandolin – Norman*Vocals – John*Written-By – John Hartford Boogie A5 1:12 Vocals – John*Written-By – John Hartford First Girl I Loved A6 Bass – Randy*Guitar – John*Mandolin – Norman*Viola, Cello – Vassar*Vocals – 4:32 John*Written-By – John Hartford Presbyterian Guitar A7 2:01 Bass – Randy*Guitar – John*Written-By – John Hartford With A Vamp In The Middle B1 Banjo – John*Bass – Randy*Dobro – Tut*Fiddle – Vassar*Guitar – Norman*Vocals – 3:25 John*Written-By – John Hartford Symphony Hall Rag B2 Banjo – John*Bass – Randy*Dobro – Tut*Fiddle – Vassar*Guitar – Norman*Written-By – 2:45 John Hartford Because Of You B3 0:59 Guitar – John*Vocals – John*Written-By -

Nitty Gritty Dirt Band

NITTY GRITTY DIRT BAND With a refreshed lineup and newfound energy, The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band remains one of the most accomplished bands in American roots music. Following an extended 50th anniversary tour, the ensemble grew to a six-piece in 2018 for the first time since their early jug band days. The group now includes Jeff Hanna (acoustic guitar, electric guitar), Jimmie Fadden (drums, harmonica), Bob Carpenter (keyboards), Jim Photoglo (bass, acoustic guitar), Ross Holmes (fiddle, mandolin), and Jaime Hanna (electric and acoustic guitar). All six members also sing, and when their voices merge, the harmonies add a powerful new component for the legendary band. And with the father-son pairing of Jeff and Jaime Hanna, the band carries on a country music tradition of blood harmony. Jeff Hanna says, “It’s like when you throw a couple of puppies into a pen with a bunch of old dogs. All of a sudden, the old dogs start playing, you know? That’s kind of what’s happened with us. The basic vibe is so up and positive, and the music– we’re hearing surprises from Jaime and Ross all night. And they’re encouraging us in the same way to take more chances. It’s opened a lot of doors for us, musically, and the morale is really great. That’s important for a band that’s been out there for over 53 years.” The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band played their first gig in 1966 in Southern California as a jug band and by 1969 had become a cornerstone of the burgeoning country-rock community. -

Soundings East

Soundings East Volume 39 Spring 2017 Soundings East Soundings East Volume 39 TABLE OF CONTENTS CLAIRE KEYES POETRY AWARD Winner Faith Shearin Darwin’s Daughter ................................................................................. 2 My Grandmother, Swimming ................................................................. 3 My Mother, Getting Dressed .................................................................. 4 Ruined Beauty ........................................................................................ 5 Escapes ................................................................................................... 6 Old Woman Returns to Rosebank Avenue ............................................. 7 Adam and Eve in Couples Therapy ......................................................... 8 In This Photo of My Father ..................................................................... 9 Phrenology .............................................................................................10 Northwest Passage .................................................................................11 CLAIRE KEYES STUDENT POETRY AWARD Winner Rebekah Aran In the Heat .......................................................................................... 12 Runner-Up Felicia LeBlanc 3 am ...................................................................................................... 13 FICTION Ryan Burruss The Great Flood ....................................................................................17 John DeBon -

The Unbroken Circle the Musical Heritage of the Carter Family

The Unbroken Circle The Musical Heritage Of The Carter Family 1. Worried Man Blues - George Jones 2. No Depression In Heaven - Sheryl Crow 3. On The Sea Of Galilee - Emmylou Harris With The Peasall - Sisters 4. Engine One-Forty-Three - Johnny Cash 5. Never Let The Devil Get - The Upper Hand Of You - Marty Stuart And His Fabulous - Superlatives 6. Little Moses - Janette And Joe Carter 7. Black Jack David - Norman And Nancy Blake With - Tim O'brien 8. Bear Creek Blues - John Prine 9. You Are My Flower - Willie Nelson 10. Single Girl, Married Girl - Shawn Colvin With Earl And - Randy Scruggs 11. Will My Mother Know - Me There? The Whites - With Ricky Skaggs 12. The Winding Stream - Rosanne Cash 13. Rambling Boy - The Del Mccoury Band 14. Hold Fast To The Right - June Carter Cash 15. Gold Watch And Chain - The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band - With Kris Kristofferson Produced By John Carter Cash (except "No Depression" produced by Sheryl Crow) Engineered And Mixed By Chuck Turner (except "Engine One-Forty-Three" mixed by John Carter Cash) Executive Assistant To The Producer Andy Wren Mixing Assistant Mark "Hank" Petaccia Recorded at Cash Cabin Studio, Hendersonville, Tennessee unless otherwise listed. Mixed at Quad Studios, Nashville, Tennessee All songs by A.P. Carter Peer International Corp. (BMI) Lyrics reprinted by permission. The Production Team Would Like To Thank: Laura Cash, Anna Maybelle Cash, Joseph Cash, Skaggs Family Records, Joseph Lyle, Mark Rothbaum, LaVerne Tripp, Debbie Randal, The guys at Underground Sound, Rita Forrester, Flo Wolfe, Dale Jett, Pat and Sharen Weber, Hope Turner, Chet and Erin, Connie Smith, Lou and Karen Robin, Cathy and Bob Sullivan, Kirt Webster, Bear Family Records, Wayne Woodard, Mark Stielper, Carlene, Renate Damm, Lin Church, David Ferguson, Kelly Hancock, Karen Adams, Lisa Trice, Lisa Kristofferson and kids, Nancy Jones, DS Management, Rick Rubin, Ron Fierstein, Les Banks, John Leventhal, Sumner County Sheriff's Department, our buddies at TWRA, and most of all God.