Soundings East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Spring Voices

VOICES FROM THE WRITING CENTER SPRING 2015 A CELEBRATION OF WRITING DONE IN AND AROUND THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA WRITING CENTER EDITED BY CASSANDRA BAUSMAN TABLE OF CONTENTS From Father to Son, Tanner King ................................................ 3 Forget Me Not , De'Shea Coney .................................................. 6 Standoff, Devin Van Dyke ........................................................ 11 Storm of War, Abe Kline ......................................................... 113 Wilderness Appreciation, Natalie Himmel .................................. 17 The Sticky Note, Mingfeng Huang ............................................ 22 Odd and Even, Wenxiu Zou ...................................................... 26 World Apart (Excerpt), Cody Connor .................................... 44 Narrativa, Sarah Jansen ............................................................. 57 Why Everyone Should "Bilbo Up', Sarah Kurtz...........................59 Authoethnography, Ying Chen......................................................62 Voir Dire, Raquel Baker.............................................................64 2 FROM FATHER TO SON Stepping over one childhood memory after another, I make my way toward the chest. I look into it, and there it is, TANNER KING staring up at me. A faded brown teddy bear, with so many patches and stitch jobs that I wonder how much of the original The front door of the old farmhouse opens with a loud fabric is actually there. It looks like it could be centuries old. creak, and my childhood living room greets me as if no time has Maybe it is. It has black beads for eyes, one of which is hanging passed. This is clearly not the case. Plaster is missing from the loosely by a thread. The other one looks up at me, as if it's wall in large chunks, some of it to be found on the dusty brown wondering where I've been. sofa sitting against the staircase to my right. Graffiti litters the Written down the inside of its right leg is “ALBert.” My walls, covering up what is left of the brown striped wallpaper. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 12 AUGUST 1ST, 2016 August 1, 2016 Up the Ladder INCOMING LETTERS Written by Paul McGowan I am responding to the recent article on DACs and the quick brush-off of ladder DACs. (Richard Murison’s “My Kingdom for a DAC”, Richard didn’t brush off ladder DACs so much as say that they were damned hard to build properly --Ed.) There are several R2R or ladder DACs on the market and in my opinion and that of many others they are far superior to any delta-sigma DAC on the market. The best example is the Audio-GD Master 7 dac. Also, the great Audio Note DACs are ladder DACs. These DACs have a musicallity that delta- sigma DACs dream about. Delta-sigma dacs are used mostly because R2R chips are simply too difficult and expensive to make.The old R2R chips are expensive, hard to find and no longer in production. I believe Mytek is making an R2R chip and Audio Note has one in development. Did a recent comparison of my Master 7 with a friend’s DCS stack and even he thought the Master 7 was better. The DCS is 10 times the price. Yes, a ladder DAC will not do DSD, but for me that is no great loss. Alan Hendler Doesn't Like Tchaikovsky Either Three cheers for Mr. Schenbeck. He writes concisely and entertainingly and, with his adroit embedding of musical examples, uses the electronic magazine format as it should be used. I look forward to each of his contributions. Never much liked Tchaikovsky either. -

2638 3 Britney Spears 5934 22 Lily Allen 8573 22 Taylor Swift 8771 99

2638 3 Britney Spears 5934 22 Lily Allen 8573 22 Taylor Swift 8771 99 Toto 9153 911 Wyclef Jean 4440 1973 James Blunt 8210 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 5019 1994 Jason Aldean 7092 1999 Prince 8341 5678 Steps 4158 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan 713 03 Bonnie & Clyde Beyonce 4540 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z 10666 1 Thing Amerie 3822 10 Million People Example 3061 1-2-3-4 Sumpin' New Coolio 7319 16 Tons Robbie Williams 8185 18 & Life Skid Row 8194 1-800-273-8255 Logic 7806 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones 8737 2 4 6 8 Motorway Tom Robinson 8286 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 8505 20th Century Boy T. Rex 4206 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 9129 21st Century Girl Willow Smith 2690 24K Magic Bruno Mars 2907 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 7353 29 Palms Robert Plant 853 2U David Guetta 898 2U Justin Bieber 10595 3 Empty Words Shawn Mendes 8810 3 Miles High Travis 5983 3 Times A Lady Lionel Richie 2895 3 Words Cheryl Cole 10894 30 Days Saturdays 6282 3am Matchbox 20 6315 3am Meghan Trainor 4240 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 6120 4 Minutes Madonna 976 4 Seasons Of Loneliness Boyz Ii Men 9502 42nd Street 42nd Street 8471 48 Crash Suzi Quatro 4858 5 1 5 0 Dierks Bentley 6917 50 Ways To Leave Your Lover Paul Simon 8795 50 Ways To Say Goodbye Train 6266 500 Miles Mary & Paul & Peter 4748 500 Miles Away From Home Bobby Bare 4319 500 Miles Away From Home Hooters 9135 634 5789 Wilson Pickett 3079 7 Days Craig David 6474 7 Things Miley Cyrus 6075 7 Years Lukas Graham 4219 7 Yeas And 50 Days Groove Coverage 9855 76 Trombones Music Man 5596 9 Million Bicycles Katie Melua 3385 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 4541 99 Problems Jay-Z 10737 A Billion Girls Elyar Fox 5187 A Broken Wing Martina McBride 4997 A Country Boy Can Survive Hank Williams Jr. -

41 Kult NT.Qxp

DAGSAVISEN NYE TAKTERKULTUR TIRSDAG 18. OKTOBER 2005 41 Sylvians fire årtier 70-TALLET Danner bandet Japan i 1974 sammen med broren Steve og skifter navn fra Norge David Batt til David Sylvian. Blir oppdaget av den senere så beryktede manageren Simon Napier-Bell (Wham m.m.). Gir ut to lite vellykkede glam-rock-pregede album, men tittelkuttet på tredjeplata «Quiet Life» (1979) peker mot noe mer sofistikert og særpreget. 80-TALLET Med platene «Gentlemen Take Polaroids» (1980) og «Tin Drum» (1981) utvikler Japan en egenartet asia- tiskinspirert sound, og får en hit med den minimalis- tiske balladen «Ghosts». Oppløses i 1982 etter mye intern krangel. Sylvian begynner å samarbeide med eksperimentelle musikere som Riuichi Sakamoto, Robert Fripp (King Crimson) og Holger Czukay (Can). Gir ut sitt første soloalbum «Brilliant Trees» (1984), følger opp med doble «Gone To Earth» (1986) og «Secrets Of The Beehive» (1987), som alle har status som kultklassikere. Jobber også innen teater, foto- kunst og dans. 90-TALLET Japan gjenforenes under navnet Rain Tree Crow, lager et halvbra album og oppløses igjen. Sylvian flytter til USA og gifter seg med Prince-protesje- en Ingrid Chavez. Lager en del instrumental ambient- musikk, gjenopptar sam- arbeidet med Robert Fripp på duoalbumene «The First Day» (1993) og FOTO: KEVIN WESTERBERG/DOT «Redemption» (1994), som ikke hører til hans sterkeste. Gir ut sitt første viteten. Jeg følte at jeg var i ferd med å bli kvalt av tenkt å gå tilbake til å lage tradisjonelle låter igjen. soloalbum siden 1987, min egen historie. Det var svært frigjørende å bli fer- Nine Horses-plata er ikke nødvendigvis en indika- «Dead Bees On A Cake» dig med kontrakten og bygge mitt eget studio. -

Candidates Accelerate Electioneering

RE5PON5IBLE REFRE5ENT/ Candidates Accelerate Electioneering (UNICOL I, out cliff STUDENT GOVERNMENT Candidates lot' ASB executive and legislative po- lots for two representatives to Student Council. kins (SPUR), Bob Atmstrong Election Board Heisterberg. sitions are in the Gnat stages of electioneering for next A new rule set forth by the ASB states, "that write-in candidates are duly elected only GRADUATE RACE week's elections. when he receives at least the required number of votes Three graduate students are in the race for two A maze of campaign posters, handouts galore and which equals the number of signatures required on the graduate representative seats on Student C'ouncil. They hand shaking candidates will greet students now until petition to run for office. are Ray Kunde (SPUR), Patty Givens t UNICOL(, and after the polls close at 7:30 p.m. next Thursday. Richard Epstein. QUALIFICATIONS have filed petitions for senior repre- Ken Lane, ASB election chairman, predicts 3-4,000 Nine persons Harold Kushins (UNI('OL), Dick students will vote in the upcoming election. Last year The present petition qualification for executive sentative and include J. Fraser (SPUR), Larry Collins a total of 2,818 cast ballots. officers is 100 signatures, and council representatives Miner I SPUR), J. Ann Latiderback (SPUR), Polling places will be located in front of the col- must have 50 signatures. (UNICOL), Jack Grady, Lowry (SPUR) and Vincent Con- lege bookstore, on Seventh Street, In front of the Campaigning tur ASB Presidential votes are, ac- Margaret Leshin, Gil . cafeteria and on Seventh Street across from the cording to their ballot positions, Gene Lokey (UNICOL), treras I. -

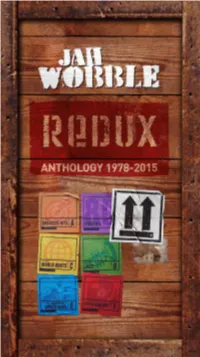

View the Redux Book Here

1 Photo: Alex Hurst REDUX This Redux box set is on the 30 Hertz Records label, which I started in 1997. Many of the tracks on this box set originated on 30 Hertz. I did have a label in the early eighties called Lago, on which I released some of my first solo records. These were re-released on 30 Hertz Records in the early noughties. 30 Hertz Records was formed in order to give me a refuge away from the vagaries of corporate record companies. It was one of the wisest things I have ever done. It meant that, within reason, I could commission myself to make whatever sort of record took my fancy. For a prolific artist such as myself, it was a perfect situation. No major record company would have allowed me to have released as many albums as I have. At the time I formed the label, it was still a very rigid business; you released one album every few years and ‘toured it’ in the hope that it became a blockbuster. On the other hand, my attitude was more similar to most painters or other visual artists. I always have one or two records on the go in the same way they always have one or two paintings in progress. My feeling has always been to let the music come, document it by releasing it then let the world catch up in its own time. Hopefully, my new partnership with Cherry Red means that Redux signifies a new beginning as well as documenting the past. -

Miley Cyrus E Disney Channel: Análise De Uma Crise De Imagem No Universo Teen

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO CENTRO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS JORNALISMO MILEY CYRUS E DISNEY CHANNEL: ANÁLISE DE UMA CRISE DE IMAGEM NO UNIVERSO TEEN ELISA PAIXÃO MACHADO RIO DE JANEIRO 2017 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO CENTRO DE FILOSOFIA E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS JORNALISMO MILEY CYRUS E DISNEY CHANNEL: ANÁLISE DE UMA CRISE DE IMAGEM NO UNIVERSO TEEN Monografia submetida à Banca de Graduação como requisito para obtenção do diploma de Comunicação Social/ Jornalismo. ELISA PAIXÃO MACHADO Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Gabriela Nóra Pacheco Latini RIO DE JANEIRO 2017 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO DE JANEIRO ESCOLA DE COMUNICAÇÃO TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO A Comissão Examinadora, abaixo assinada, avalia a Monografia Miley Cyrus e Disney Channel: análise de uma crise de imagem no universo teen, elaborada por Elisa Paixão Machado. Monografia examinada: Rio de Janeiro, no dia ........./........./.......... Comissão Examinadora: Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Gabriela Nóra Pacheco Latini Doutora em Comunicação pela Escola de Comunicação - UFRJ Departamento de Comunicação - UFRJ Profa. Dra. Cristiane Henriques Costa Doutora em Comunicação pela Escola de Comunicação - UFRJ Departamento de Comunicação -. UFRJ Profa. Dra. Patrícia Cardoso D’Abreu Doutora em Comunicação pelo Instituto de Artes e Comunicação - UFF Departamento de Comunicação - UFRJ RIO DE JANEIRO 2017 FICHA CATALOGRÁFICA MACHADO, Elisa Paixão. Miley Cyrus e Disney Channel: análise de uma crise de imagem no universo teen. Rio de Janeiro, 2017. MonograFia (Graduação em Comunicação Social/ Jornalismo) – Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro – UFRJ, Escola de Comunicação – ECO. Orientadora: Gabriela Nóra Pacheco Latini MACHADO, Elisa Paixão. Miley Cyrus e Disney Channel: análise de uma crise de imagem no universo teen. -

Funny Feelings: Taking Love to the Cinema with Woody Allen

FUNNY FEELINGS: TAKING LOVE TO THE CINEMA WITH WOODY ALLEN by Zorianna Ulana Zurba Combined Bachelor of Arts Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario, 2004 Masters of Arts Brock University, St. Catherines, Ontario, 2008 Certificate University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, 2009 A dissertation presented to Ryerson University and York University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program of Communication and Culture. Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2015 ©Zorianna Zurba 2015 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this dissertation. This is a true copy of the dissertation, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University and York University to lend this dissertation to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research I further authorize Ryerson University and York University to reproduce this dissertation by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my dissertation may be made electronically available to the public. ii Funny Feelings: Taking Love to the Cinema with Woody Allen Zorianna Zurba, 2015 Doctor of Philosophy in Communication and Culture Ryerson University and York University Abstract This dissertation utilizes the films of Woody Allen in order to position the cinema as a site where realizing and practicing an embodied experience of love is possible. This dissertation challenges pessimistic readings of Woody Allen’s film that render love difficult, if not impossible. By challenging assumptions about love, this dissertation opens a dialogue not only about the representation of love, but the understanding of love. -

Semiotic Analysis)

LOVE IN THE BEATLES’ SELECTED SONG LYRICS (SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS) THESIS By; Mahardika Reza Lesmana NIM 14320061 ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2018 i LOVE IN THE BEATLES’ SELECTED SONG LYRICS (SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS) THESIS Presented to Universitas Islam Negeri Maulana Malik Ibrahim Malang In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Sarjana Sastra (S.S) Advisor: Muzakki Afifuddin, M.Pd. 197610112011011005 By: Mahardika Reza Lesmana 14320061 ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI MAULANA MALIK IBRAHIM MALANG 2018 ii iii iv v MOTTO Fall seven times, stand up eight! vi DEDICATION I proudly dedicate this thesis to my father Drs. Eko Wahyudianto, my mother Dra. Larasati, and my twin brother Mahardika Bima Baskara A.Md. Thank you so much for every single thing you do to me and I am feeling so blessed that i can be a part of this world paradise called family. vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Alhamdulillah, all praises belong to Allah SWT who has given me the strength and guidance until I can finish the thesis entitled “Love in The Beatles’ Selected Song Lyrics (Semiotic Analysis)”. And I do not forget to uphold my sholawat and salam to my beloved Prophet Muhammad SAW, who has brought all people from the darkness to the lightness. I afford to accomplish this thesis succesfully because of some talented people who always give advice, guidance and critics in order to make betterment for this thesis. Therefore, in this great opportunity, I would like to extend the great gratitude and highest appreciation to: Prof Dr. -

WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS 1970 to 1982

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS 1970 to 1982 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, APRIL 2019 WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS, 1970–1982 A BRIEF WARNER BROS. / WEA HISTORY WIKIPEDIA TELLS US THAT... WEA’S ROOTS DATE BACK TO THE FOUNDING OF WARNER BROS. RECORDS IN 1958 AS A DIVISION OF WARNER BROS. PICTURES. IN 1963, WARNER BROS. RECORDS PURCHASED FRANK SINATRA’S REPRISE RECORDS. AFTER WARNER BROS. WAS SOLD TO SEVEN ARTS PRODUCTIONS IN 1967 (FORMING WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS), IT PURCHASED ATLANTIC RECORDS AS WELL AS ITS SUBSIDIARY ATCO RECORDS. IN 1969, THE WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS COMPANY WAS SOLD TO THE KINNEY NATIONAL COMPANY. KINNEY MUSIC INTERNATIONAL (LATER CHANGING ITS NAME TO WARNER COMMUNICATIONS) COMBINED THE OPERATIONS OF ALL OF ITS RECORD LABELS, AND KINNEY CEO STEVE ROSS LED THE GROUP THROUGH ITS MOST SUCCESSFUL PERIOD, UNTIL HIS DEATH IN 1994. IN 1969, ELEKTRA RECORDS BOSS JAC HOLZMAN APPROACHED ATLANTIC'S JERRY WEXLER TO SET UP A JOINT DISTRIBUTION NETWORK FOR WARNER, ELEKTRA, AND ATLANTIC. ATLANTIC RECORDS ALSO AGREED TO ASSIST WARNER BROS. IN ESTABLISHING OVERSEAS DIVISIONS, BUT RIVALRY WAS STILL A FACTOR —WHEN WARNER EXECUTIVE PHIL ROSE ARRIVED IN AUSTRALIA TO BEGIN SETTING UP AN AUSTRALIAN SUBSIDIARY, HE DISCOVERED THAT ONLY ONE WEEK EARLIER ATLANTIC HAD SIGNED A NEW FOUR-YEAR DISTRIBUTION DEAL WITH FESTIVAL RECORDS. IN MARCH 1972, KINNEY MUSIC INTERNATIONAL WAS RENAMED WEA MUSIC INTERNATIONAL. DURING THE 1970S, THE WARNER GROUP BUILT UP A COMMANDING POSITION IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY. IN 1970, IT BOUGHT ELEKTRA (FOUNDED BY HOLZMAN IN 1950) FOR $10 MILLION, ALONG WITH THE BUDGET CLASSICAL MUSIC LABEL NONESUCH RECORDS. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 106 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 106 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 146 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 15, 2000 No. 29 Senate The Senate was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Monday, March 20, 2000, at 12 noon. House of Representatives WEDNESDAY, MARCH 15, 2000 The House met at 10 a.m. and was God of hope, fill us with joy and ican workers are being left behind un- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- peace as we trust in You that, by the employed and unable to reach the pore (Mr. OSE). power of Your spirit, our whole life and American dream. And in spite of this f outlook may be radiant with hope. indisputable fact, the Clinton adminis- Amen. tration continues to encourage the ex- DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER f pansion of current free trade policy, PRO TEMPORE such as NAFTA, to other nations The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- THE JOURNAL around the world. fore the House the following commu- The SPEAKER pro tempore. The Sadly, the President has also failed nication from the Speaker: Chair has examined the Journal of the to mention another fact that the Com- WASHINGTON, DC, last day's proceedings and announces merce Department also announced, and March 15, 2000. to the House his approval thereof. that is that the United States experi- I hereby appoint the Honorable DOUG OSE Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- enced record trade deficits with its to act as Speaker pro tempore on this day. -

T H E I N F O R M E

T H E I N F O R M E R S Screenplay by Bret Easton Ellis & Nicholas Jarecki Based on the book "The Informers" by Bret Easton Ellis Black water flickers with light. Suddenly a pool is radiated an intense aqua blue. The sounds of a party fade in along with the ominous opening of The Go-Go's "This Town". A party in the backyard of a Bel Air mansion. 1983. It's paradisiacal: huge flowering trees lit by ground lamps, the massive steaming pool, a giant fountain spraying water, an endless maze of gardens, a house the size of a hotel looming over the scene. It's a dream, a mirage. The college kids that make-up the party are all interchangeable: blond, beautiful, tan. And everyone is dressed in the clothing of the era: pastels, Polo shirts with the collars up, tight jeans, pennyloafers, mini-skirts and Camp Beverly Hills tank-tops. GRAHAM (21) and CHRISTIE (19) are two of these perfect specimens. They make-out while sharing a joint on a chaise lounge by the pool. They blow smoke into each other's mouths and kiss hungrily, oblivious to the rest of the party. On the chaise lounge opposite them: MARTIN (20) and TIM (20). Tim does bumps of coke from a vial and is talking nonstop at Martin who just sips a Corona and stares coolly at the couple grinding into each other on the chaise. We can't hear anybody because of the music. BRUCE (20) makes his way down the steps leading to the pool, followed by a drunken RAYMOND (20), who's trying to explain something to him.