ANNELINN – PAST and PRESENT the Development of Annelinn and the Experience of the Residents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

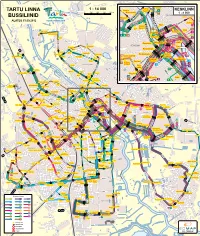

Tartu Linna Bussiliinid

E E E 21 Raadi E Raadi E r 4 P e E o pk so u m 3 i r 9 ur ie M s u t N ee RAADI-KRUUSAMÄE t Aiandi n m v Pärna a akraa v e koguj Nurme r õõbus V E a N Risti a Jänese rn E ä E P Orava Risti E E Peetri St EE aa kirik E di E Peetri kirik M on A i Peetri kirik Narvamäe JÕ Tartu Näitused Laululava G I Narvamäe E a n E Piiri u E Sa Kasarmu 8 Maaülikool P Vene ui E E e E Palmi- Mur s E i E s 1 : 14 000 E oo pk t E Herne KESKLIeNN E SUPILINN r Tuglase E hoone 4 E e TARTU LINNA 0 250 500 750 1 000 m E a E Kroonuaia i E a 7 1 : 8 000 Tuglase E F Kreutzwaldi u E E .R ÜLEJÕE E .K n E Puiestee Kreutzwaldi r o N 13 JAAMAMÕISA BUSSILIINID eu Kloostri o EEE E tzw r a a E K r E ALATES 03.09.2012 ld 16A E v t i E se s e a u p ii V at Jaama E i a H Hurda E a a m a E L Kivi R j E E Hurda b 18 h Palmi- n E Hiie Ta õ BeE tooni a TÄHTVERE a t E E r hoone E J P E d a Lai 7 E E 16 Paju aa 10 Hiie ps u E Pikk m E E E a Sõpruse pst. -

Rmk Annual Report 2019 Rmk Annual Report 2019

RMK ANNUAL REPORT 2019 RMK ANNUAL REPORT 2019 2 RMK AASTARAAMAT 2019 | PEATÜKI NIMI State Forest Management Centre (RMK) Sagadi Village, Haljala Municipality, 45403 Lääne-Viru County, Estonia Tel +372 676 7500 www.rmk.ee Text: Katre Ratassepp Translation: TABLE OF CONTENTS Interlex Photos: 37 Protected areas Jarek Jõepera (p. 5) 4 10 facts about RMK Xenia Shabanova (on all other pages) 38 Nature protection works 5 Aigar Kallas: Big picture 41 Põlula Fish Farm Design and layout: Dada AD www.dada.ee 6–13 About the organisation 42–49 Visiting nature 8 All over Estonia and nature awareness Typography: Geogrotesque 9 Structure 44 Visiting nature News Gothic BT 10 Staff 46 Nature awareness 11 Contribution to the economy 46 Elistvere Animal Park Paper: cover Constellation Snow Lime 280 g 12 Reflection of society 47 Sagadi Forest Centre content Munken Lynx 120 g 13 Cooperation projects 48 Nature cameras 49 Christmas trees Printed by Ecoprint 14–31 Forest management 49 Heritage culture 16 Overview of forests 19 Forestry works 50–55 Research 24 Plant cultivation 52 Applied research 26 Timber marketing 56 Scholarships 29 Forest improvement 57 Conference 29 Forest fires 30 Waste collection 58–62 Financial summary 31 Hunting 60 Balance sheet 62 Income statement 32–41 Nature protection 63 Auditor’s report 34 Protected species 36 Key biotypes 64 Photo credit 6 BIG PICTURE important tasks performed by RMK 6600 1% people were employed are growing forests, preserving natural Aigar Kallas values, carrying out nature protection of RMK’s forest land in RMK’s forests during the year. -

Soviet Housing Construction in Tartu: the Era of Mass Construction (1960 - 1991)

University of Tartu Faculty of Science and Technology Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences Department of Geography Master thesis in human geography Soviet Housing Construction in Tartu: The Era of Mass Construction (1960 - 1991) Sille Sommer Supervisors: Michael Gentile, PhD Kadri Leetmaa, PhD Kaitsmisele lubatud: Juhendaja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Juhendaja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Osakonna juhataja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Tartu 2012 Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Literature review ................................................................................................................................. 5 Housing development in the socialist states .................................................................................... 5 From World War I until the 1950s .............................................................................................. 5 From the 1950s until the collapse of the Soviet Union ............................................................... 6 Socio-economic differentiations in the socialist residential areas ................................................... 8 Different types of housing ......................................................................................................... 11 The housing estates in the socialist city .................................................................................... 13 Industrial control and priority sectors .......................................................................................... -

Uuring "Asustuse Arengu Suunamine Ja Toimepiirkondade Määramine"

Tartumaa maakonnaplaneering Asustuse arengu suunamine ja toimepiirkondade määramine Tellija: Tartu Maavalitsus Teostajad: Antti Roose ja Martin Gauk Tartu 2014 SISUKORD Sissejuhatus ............................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Tiheasulate piiritlemine Tartumaal ................................................................................................. 5 1.1. Ettepanekud asustuse suunamiseks ........................................................................................... 21 2. Tootmis-, äri- ja logistikaalad ........................................................................................................ 25 3. Tartumaa toimepiirkonnad ........................................................................................................... 28 Allikad .................................................................................................................................................... 35 Sissejuhatus Tartu maakonnaplaneering, mis kehtestati Tartu maavanema 23. aprilli 1999. a korraldusega nr 1537, on tingituna olulistest linnastumise ja teisalt ääremaastumise protsessidest aegunud ega saa olla lähtealuseks üldplaneeringute ja teiste asustuse arengut suunavate planeeringute koostamisele 15ne aasta möödudes. Planeeringuliselt on kõige põhimõttelisem Tartu ümbruse asustuse suunamine, sest sinna on tekkinud ja üsnagi vabalt arenemas täiesti uut tüüpi eeslinna-asustus. Uue Tartu maakonnaplaneeringu algatas -

Elukeskkonnaga Rahulolu Hindamise Metoodika Täiendusvõimalused Ja Andmete Kasutamine Säästva Arengu Suunamisel Uuringu Lõpparuanne

Elukeskkonnaga rahulolu hindamise metoodika täiendusvõimalused ja andmete kasutamine säästva arengu suunamisel Uuringu lõpparuanne Tellija: Rahandusministeerium, Kultuuriministeerium 30. aprill 2021 Uuring: Elukeskkonnaga rahulolu hindamise metoodika täiendusvõimalused ja andmete kasutamine säästva arengu suunamisel Uuringu autorid: Kaido Väljaots Keiti Kljavin Tõnu Hein Raul Kalvo Kristina Hiir Sille Sepp Anna-Kaisa Adamson Annela Pajumets Aima Allik Mart Kevin Põlluste Uuringu teostajad: HeiVäl OÜ / HeiVäl Consulting ™ Lai 30, 51005 Tartu www.heival.ee [email protected] +372 740 7124 Uuringu tellija: Rahandusministeerium, Kultuuriministeerium Uuring viidi läbi perioodil juuli 2020 – aprill 2021. Elukeskkonnaga rahulolu hindamise metoodika täiendusvõimalused ja andmete kasutamine säästva arengu suunamisel 2 Smart Analysis by HeiVäl Consulting / www.heival.ee SISUKORD 1. SISSEJUHATUS ................................................................................................................................... 4 Uuringu eesmärk ja lähteülesanne 4 2. ELUKESKKONNAGA RAHULOLU MÕISTE .................................................................................. 5 Elukeskkonna mõiste kujunEmise ülevaade 5 Erinevad mudelid elukeskkonna hindamiseks 6 Rahulolu hindamine 9 3. ELUKESKKONNAGA RAHULOLU MÕÕTMISE KOGEMUS TEISTES RIIKIDES .................. 13 Rahulolu mõõtmine välismaal 13 Austraalia kogemus. Linna elamisväärsuse indeks 13 Soome kogemus. SYKE uuring 16 ÜRO säästva arengu eesmärgid 20 4. STATISTIKAAMETI ARVAMUSKÜSITLUSE SEOSED .............................................................. -

Landscape Urbanism and Green Infrastructure. 2019.Pdf

Landscape Urbanism and Green Infrastructure Edited by Thomas Panagopoulos Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Land www.mdpi.com/journal/land Landscape Urbanism and Green Infrastructure Landscape Urbanism and Green Infrastructure Special Issue Editor Thomas Panagopoulos MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Thomas Panagopoulos University of Algarve Portugal Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Land (ISSN 2073-445X) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/land/special issues/greeninfrastructure) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03921-369-6 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03921-370-2 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Thomas Panagopoulos. c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Thomas Panagopoulos Special Issue: Landscape Urbanism and Green Infrastructure Reprinted from: Land 2019, 8, 112, doi:10.3390/land8070112 ...................... 1 Jon Bryan Burley The Emergence of Landscape Urbanism: A Chronological Criticism Essay Reprinted from: Land 2018, 7, 147, doi:10.3390/land7040147 ..................... -

Events Concerts Stage

TARTU I MARCH I 2011 Events 2.3: Art-house film “Das Leben der 18.–20.3: “Summer 2011” in Tartu Näitused Anderen” in Athena Centre. A sarcastic Fairs Centre. Ticket 3,50/2,50 EUR political drama set in the cultural circles (54,76/39,12 EEK). www.tartunaitused.ee/ of East Berlin in 1984 focuses on the writer suvi Georg Dreyman. Ticket 4/3 EUR 18.–20.3: “Motoexotika 2011” in Tartu (62,59/46,94 EEK). www.athena.ee Näitused Fairs Centre. Ticket 3,50/2,50/0 EUR 2.3: Art-house film “Banksy – Exit Through (54,76/39,12/0 EEK). kultuuriaken.tartu.ee the Gift Shop” in Athena Centre. Thierry 22.–25.3: Forum theatre training for Guerry is a Frenchman living in Los Angeles youngsters in Lille House. Ticket 10 EUR whose biggest passion is his camcorder. (156,47 EEK). www.lille.tartu.ee/kevad2011 www.athena.ee 21.–27.3: Tartu Visual Culture Festival 12.3: Dance performance “Zuga zuug zuh- “Wordlfilm”. www.worldfilm.ee zuh-zuh” in Toy Museum. Dance meets play. A train ride evoked by movement, sounds, 26.3: Youngsters fashion contest music. Ticket 4,79 EUR (75 EEK). teatrikodu.ee “European Patterns” in Tasku Centre. www.tartunoored.ee 15.3: “Eyes on Screen” – a film and discussion evening. For free. kultuuriaken.tartu.ee 27.–28.3: Tartu school theatre festival “Play Days” in Harbour Theatre. For free. 15.3: Matsalu 8th Nature Film Festival kultuuriaken.tartu.ee evening in Tartu Environmental Education Centre. Ticket 2/1 EUR (31,29/15,65 EEK). -

EESTI MAAÜLIKOOL Katri Vene KIIRABIKUTSETE JAOTUVUS

EESTI MAAÜLIKOOL Põllumajandus- ja keskkonnainstituut Katri Vene KIIRABIKUTSETE JAOTUVUS ELANIKKONNA RISKIRÜHMADE ALUSEL TARTU LINNAS KUUMALAINETE JA KUUMAPÄEVADE AJAL DIVISION OF AMBULANCE CALLS ON THE BASIS OF POPULATION RISK GROUPS IN TARTU CITY DURING HEAT WAVES AND HOT DAYS Magistritöö Linna- tööstusmaastike korralduse õppekava Juhendaja: prof. Kalev Sepp, PhD Tartu, 2017 Eesti Maaülikool Kreutzwaldi 1, Tartu 51014 Magistritöö lühikokkuvõte Autor: Katri Vene Õppekava: Linna- ja tööstusmaastike korraldus Pealkiri: Kiirabikutsete jaotuvus elanikkonna riskirühmade alusel Tartu linnas kuumalainete ja kuumapäevade ajal Lehekülgi: 78 Jooniseid: 27 Tabeleid: 3 Lisasid: 4 Osakond: Põllumajandus- ja keskkonnainstituut Uurimisvaldkond (ja mag. töö puhul valdkonna kood): Linna ja maa planeerimine (S240) Juhendaja(d): prof. Kalev Sepp Kaitsmiskoht ja -aasta: Tartu, 2017 Kuumalained on looduslikest ohtudest üks tähelepanuväärsemaid, kuid vaatamata tõsistele tagajärgedele pööratakse neile siiski vähe tähelepanu. Kuumalaine avaldab ühiskonnale märkimisväärset mõju suurendades muuhulgas ka suremuse riski. Uurimistöö eesmärgiks on tuvastada kuumalainete ja kuumapäevade esinemised Tartu linnas ning hinnata kiirabi väljakutsete sagedust, iseloomu ja paiknemist linnaruumis elanikkonna riskirühmade alusel antud perioodidel. Uurimistöös kasutatakse materjali saamisel kahte andmebaasi- Tartu Observatooriumi õhutemperatuuride jaotuvustabelit ning KIIRA andmebaasi. Maakatte tüüpide analüüsimiseks on kasutatud Maa- ameti Eesti topograafia andmekogu põhikaarti -

Network Connections and Neighbourhood Perception

Architecture and Urban Planning doi: 10.1515/aup-2017-0010 2017 / 13 Network Connections and Neighbourhood Perception: Using Social Media Postings to Capture Attitudes among Twitter Users in Estonia Daniel Baldwin Hess, University at Buffalo, State University of New York Evan Iacobucci, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey Annika Väiko, University of Tartu Abstract ‒ The residential landscape of a city is key to its economic, so- control [5] and, with increasing wealth, those who can afford to cial, and cultural functioning. Following the collapse of communist rule in do so often seek alternatives to apartment blocks developed under the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) in the late 1980s and state socialism [6], [7]. For the first time in more than a half cen- early 1990s, urban residential dynamics and household mobility have been critical to urban change under new economies and political systems. This tury, consumer choice is a key dimension of the housing market article explores neighbourhood perception, which is a link in the chain to (in the Soviet Union, housing was allocated and administratively better explanation of socio-spatial processes (and their interruption by assigned) and people may now freely express their preferences the socialist system). We use a novel data set ‒ opinions expressed on one in housing type and housing location. Consequently, views and of social media (Twitter), and a novel empirical method ‒ neural network analysis, to explore people’s current attitudes and perceptions about the perceptions about apartment buildings, neighbourhoods, and neighbourhoods and districts in Tartu, Estonia. The findings suggest that districts play a role in shaping the attractiveness of places across Twitter comments about urban neighbourhoods display attitudinal and metropolitan space [8]. -

Ropka-Ihaste Looduskaitseala Kuulub Üleeuroopalisse Üleeuroopalisse Kuulub Looduskaitseala Ropka-Ihaste

Foto: Suur-rabakiil, Arne Ader Arne Suur-rabakiil, Foto: Rakko Aimar polder, Ropka-Ihaste Foto: elustik väga liigirikas. väga elustik jõed-järved – olemasolu tõttu on Ropka-Ihaste kaitseala kaitseala Ropka-Ihaste on tõttu olemasolu – jõed-järved elupaikade – luhaniit, luhasoo, roostik, Emajõe kaldavallid, kaldavallid, Emajõe roostik, luhasoo, luhaniit, – elupaikade kudepaigaks kaladele ja kahepaiksetele. Erinevate märgade märgade Erinevate kahepaiksetele. ja kaladele kudepaigaks alal väiksemad veesilmad ja Emajõe soodid, mis on heaks heaks on mis soodid, Emajõe ja veesilmad väiksemad alal - kaitse asuvad Lisaks kallastel. suudmeala Savijõe ja Porijõe Ropka-Ihaste luhaalad asuvad Emajõe, Aardla järve ning ning järve Aardla Emajõe, asuvad luhaalad Ropka-Ihaste ka tammed ja künnapuud. ja tammed ka erinevad pajuliigid, sookased, sanglepad, toomingad, kohati kohati toomingad, sanglepad, sookased, pajuliigid, erinevad mulla viljakaks. Põhilised lamminiitudel kasvavad puud on on puud kasvavad lamminiitudel Põhilised viljakaks. mulla veega uhutakse lammile hulganisti toitaineid, mis muudavad muudavad mis toitaineid, hulganisti lammile uhutakse veega suur- Kevadise lamminiitusid. ja soid – alasid liigniiskeid Emajõe kallastel asub peaaegu terve jõe ulatuses rohkesti rohkesti ulatuses jõe terve peaaegu asub kallastel Emajõe lustik E täpikhuigud, sinikaelpardid, luitsnokkpardid ja põldlõokesed. ja luitsnokkpardid sinikaelpardid, täpikhuigud, nendest arvukaimad on naerukajakad, mustviired, mustviired, naerukajakad, on arvukaimad nendest Foto: Tutkad -

![Urban Energy Planning in Tartu [PLEEC Report D4.2 / Tartu] Große, Juliane; Groth, Niels Boje; Fertner, Christian; Tamm, Jaanus; Alev, Kaspar](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3273/urban-energy-planning-in-tartu-pleec-report-d4-2-tartu-gro%C3%9Fe-juliane-groth-niels-boje-fertner-christian-tamm-jaanus-alev-kaspar-1533273.webp)

Urban Energy Planning in Tartu [PLEEC Report D4.2 / Tartu] Große, Juliane; Groth, Niels Boje; Fertner, Christian; Tamm, Jaanus; Alev, Kaspar

Urban energy planning in Tartu [PLEEC Report D4.2 / Tartu] Große, Juliane; Groth, Niels Boje; Fertner, Christian; Tamm, Jaanus; Alev, Kaspar Publication date: 2015 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Große, J., Groth, N. B., Fertner, C., Tamm, J., & Alev, K. (2015). Urban energy planning in Tartu: [PLEEC Report D4.2 / Tartu]. EU-FP7 project PLEEC. http://pleecproject.eu/results/documents/viewdownload/131-work- package-4/579-d4-2-urban-energy-planning-in-tartu.html Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Deliverable 4.2 / Tartu Urban energy planning in Tartu 20 January 2015 Juliane Große (UCPH) Niels Boje Groth (UCPH) Christian Fertner (UCPH) Jaanus Tamm (City of Tartu) Kaspar Alev (City of Tartu) Abstract Main aim of report The purpose of Deliverable 4.2 is to give an overview of urban en‐ ergy planning in the 6 PLEEC partner cities. The 6 reports il‐ lustrate how cities deal with dif‐ ferent challenges of the urban energy transformation from a structural perspective including issues of urban governance and spatial planning. The 6 reports will provide input for the follow‐ WP4 location in PLEEC project ing cross‐thematic report (D4.3). Target group The main addressee is the WP4‐team (universities and cities) who will work on the cross‐ thematic report (D4.3). The reports will also support a learning process between the cities. Further, they are relevant for a wider group of PLEEC partners to discuss the relationship between the three pillars (technology, structure, behaviour) in each of the cities. Main findings/conclusions The Estonian planning system allots the main responsibilities for planning activities to the local level, whereas the regional level (county) is rather weak. -

Rahvastiku Liikumine

Tartu linna 2017. aasta statistika on kokku pandud Tartu Linnavalitsuse töörühma poolt, kuhu kuulusid Andres Aint, Kaspar Alev, Rein Haak, Tiina Kruuse, Imbi Lang, Tiina Ligi, Alo Lilles, Lilian Lukka, Viivi Maremäe, Katrin Parv, Lennart Puksa, Riho Sulp ja Piret Väljaots ning mida juhtis abilinnapea Reno Laidre. Töörühma poolt koondatud materjali kujundasid veebisõbralikuks Tiiu Kelviste ja Johanna Victoria Lepp. Kaanefoto autor: Tarmo Haud Erinevate valdkondade statistika kogumisele aitasid kaasa alljärgnevad struktuuriüksused: Linnamajanduse osakond Asend ja keskkond Linnaplaneerimise ja maakorralduse osakond Maakasutus Linnaplaneerimise ja maakorralduse osakond Arhitektuuri ja ehituse osakond Planeerimine ja ehitus Linnaplaneerimise ja maakorralduse osakond Rahvastik Linnakantselei Ettevõtluse osakond Ettevõtlus ja tööturg Avalike suhete osakond Linnavarade osakond Linnavara Rahandusosakond Haridus Haridusosakond Tervishoid ja hoolekanne Sotsiaal- ja tervishoiuosakond Kultuur, sport ja noorsootöö Kultuuriosakond Turvalisus Linnaplaneerimise ja maakorralduse osakond Linnaeelarve Rahandusosakond Tartu linna juhtimine Avalike suhete osakond Tartu linna arenguseire näitajad Linnaplaneerimise ja maakorralduse osakond Märkide seletus: … andmeid ei ole saadud .. mõiste pole rakendatav - nähtust ei esinenud 0 näitaja väärtus väiksem kui pool kasutatud mõõtühikust – pdf dokumendile lisatud andmetabel. Avamiseks ja salvestamiseks tuleb fail eelnevat alla laadida (Mac OS kasutajatel tuleks pdf failide avamise programmiks eelnevalt määrata Adobe