Preservation by Neglect in Soviet-Era Town Planning in Tartu, Estonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

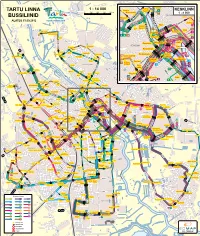

Tartu Linna Bussiliinid

E E E 21 Raadi E Raadi E r 4 P e E o pk so u m 3 i r 9 ur ie M s u t N ee RAADI-KRUUSAMÄE t Aiandi n m v Pärna a akraa v e koguj Nurme r õõbus V E a N Risti a Jänese rn E ä E P Orava Risti E E Peetri St EE aa kirik E di E Peetri kirik M on A i Peetri kirik Narvamäe JÕ Tartu Näitused Laululava G I Narvamäe E a n E Piiri u E Sa Kasarmu 8 Maaülikool P Vene ui E E e E Palmi- Mur s E i E s 1 : 14 000 E oo pk t E Herne KESKLIeNN E SUPILINN r Tuglase E hoone 4 E e TARTU LINNA 0 250 500 750 1 000 m E a E Kroonuaia i E a 7 1 : 8 000 Tuglase E F Kreutzwaldi u E E .R ÜLEJÕE E .K n E Puiestee Kreutzwaldi r o N 13 JAAMAMÕISA BUSSILIINID eu Kloostri o EEE E tzw r a a E K r E ALATES 03.09.2012 ld 16A E v t i E se s e a u p ii V at Jaama E i a H Hurda E a a m a E L Kivi R j E E Hurda b 18 h Palmi- n E Hiie Ta õ BeE tooni a TÄHTVERE a t E E r hoone E J P E d a Lai 7 E E 16 Paju aa 10 Hiie ps u E Pikk m E E E a Sõpruse pst. -

The Future of Estonia As a Flag State

FUTURE OF ESTONIA AS A FLAG STATE THE FUTURE OF ESTONIA AS A FLAG STATE DEVELOPMENT SCENARIOS UP TO 2040 riigikogu.ee/arenguseire Arenguseire Keskus 2020 THE FUTURE OF ESTONIA AS A FLAG STATE Development Scenarios up to 2040 Summary Author: Estonian Centre for Applied Research CentAR Client: Foresight Centre Compilers: Sten Anspal, Janno Järve, Tõnis Hunt, Epp Kallaste, Laura Kivi Language editor: Robin Hazlehurst Design: Eastwood Advertising, Eerik Vilk This publication is a summary of the study Competitiveness of a Flag State. Foresight on International Shipping and the Maritime Economy (Lipuriigi konkurentsivõime. Rahvusvahelise laevanduse ja meremajanduse arenguseire, 2020), which was completed as part of the Foresight Centre research into international shipping and the maritime economy. Please credit the source when using the information in this study: Estonian Centre for Applied Research CentAR, 2020. The Future of Estonia as a Flag State. Development Scenarios up to 2040. Summary. Tallinn: Foresight Centre. ISBN 978-9916-9533-1-0 (PDF) The analyses covering the field and the final report can be found on the Foresight Centre website: www.riigikogu.ee/en/foresight/laevandus-ja-meremajandus/. 2020 Acknowledgements Members of the expert committee: Tõnis Hunt (Estonian Maritime Academy of Tallinn University of Technology), Jaak Kaabel (TS Laevad), Eero Naaber (Maritime Administration), Ahti Kuningas (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications), Ants Ratas (Hansa Shipping), Marek Rauk (Maritime Administra- tion). We would also like to thank all the experts who contributed their expertise without being part of the expert committee: Patrick Verhoeven (ECSA), Jaanus Rahumägi (ESC Global Security), Illar Toomaru (Vanden Insurance Brokers), Indrek Nuut (MALSCO Law Office OÜ), Indrek Niklus (Law Office NOVE), Dan Heering (Estonian Maritime Academy of Tallinn University of Technology), Allan Noor (Amisco), Jaan Banatovski (Amisco), Valdo Kalm (Port of Tallinn), Erik Terk (Tallinn University). -

History Education: the Case of Estonia

Mare Oja History Education: The Case of Estonia https://doi.org/10.22364/bahp-pes.1990-2004.09 History Education: The Case of Estonia Mare Oja Abstract. This paper presents an overview of changes in history teaching/learning in the general education system during the transition period from Soviet dictatorship to democracy in the renewed state of Estonia. The main dimensions revealed in this study are conception and content of Estonian history education, curriculum and syllabi development, new understanding of teaching and learning processes, and methods and assessment. Research is based on review of documents and media, content analysis of textbooks and other teaching aids as well as interviews with teachers and experts. The change in the curriculum and methodology of history education had some critical points due to a gap in the content of Soviet era textbooks and new programmes as well as due to a gap between teacher attitudes and levels of knowledge between Russian and Estonian schools. The central task of history education was to formulate the focus and objectives of teaching the subject and balance the historical knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes in the learning process. New values and methodical requirements were included in the general curriculum as well as in the syllabus of history education and in teacher professional development. Keywords: history education, history curriculum, methodology Introduction Changes in history teaching began with the Teachers’ Congress in 1987 when Estonia was still under Soviet rule. The movement towards democratic education emphasised national culture and Estonian ethnicity and increased freedom of choice for schools. In history studies, curriculum with alternative content and a special course of Estonian history was developed. -

Estonia Economy Briefing: Wrapping the Year Up: in Search for a Productive Economic Reform E-MAP Foundation MTÜ

ISSN: 2560-1601 Vol. 35, No. 2 (EE) December 2020 Estonia economy briefing: Wrapping the year up: in search for a productive economic reform E-MAP Foundation MTÜ 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. [email protected] Szerkesztésért felelős személy: CHen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Huang Ping china-cee.eu 2017/01 Wrapping the year up: in search for a productive economic reform When your country’s economy is reasonably small but, to an extent, diverse, even a major crisis would not seem to be too problematic. Another story is when the pandemic substitutes ‘a major crisis’ – then there may be a dual problem of analysing the present and forecasting the future. In one of his main interviews (if not the main one), which was supposed to be wrapping the difficult year up, Estonian Prime Minister Jüri Ratas was into memorable metaphors when it would come to pure politics, but distinctly shy when a question was on economics1. During 2020, in political terms, the country was getting involved into discussing way more intra- political scandals than it would have been necessary to test the ‘health’ of a democracy. As for the process of running the economy, apart from borrowing more to survive the pandemic, the only major economic reform that the current governmental coalition managed to ‘squeeze’ through the ‘hurdles’ of the Riigikogu’s passing and the presidential approval was the so-called second pillar pension reform. The idea of the Government was to respond to a particular societal call that was, in a way, ‘inspired’ by Pro Patria and some other proponents of the prospective reform. -

Annual Report of the Chancello

Dear reader, In accordance with section 4 of the Chancellor of Justice Act, the Chancellor has to submit an annual report of his activities to the Riigikogu. The present overview of the conformity of legislation of general application with the Constitution and the laws covers the period from 1 June until 31 December 2004, and the outline of activities concerning the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms of persons, the period from 1 January until 31 December 2004. The overview contains summaries of the main cases that were settled as well as generalisations of the legal problems and difficulties, together with proposals on how to improve the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms and how to raise the quality of law making. The readers will also be able to familiarise themselves with the organisation of work in the Office of the Chancellor of Justice. According to the Constitution, the Chancellor of Justice is an independent constitutional institution. Such a status enables him to assess problems objectively and to protect people effectively from arbitrary measures of the state authority. One tool for fulfilling this task is the opportunity that the Chancellor of Justice has to submit to the Riigikogu his conclusions and considerations regarding shortcomings in legislation, in order to contribute to strengthening the principles of democracy and the rule of law. I am grateful to the members of the Riigikogu and its committees, in particular the Constitutional Committee, the Legal Affairs Committee and the Social Affairs Committee, for having been open to mutual, trustful and effective cooperation, which will hopefully continue just as fruitfully in the future. -

Liis Leitsalu Research Fellow, Institute for Genomics University of Tartu, Estonia

Liis Leitsalu Research Fellow, Institute for Genomics University of Tartu, Estonia Liis Leitsalu is a genetic consultant at the Estonian Genome Center of the University of Tartu. Her work focuses on behavioral research in genomics and the ethical, legal and societal issues related to the use of genomic information generated by the genome center. She holds a MSc in Genetic Counseling from Sarah Lawrence College (USA) and a BSc. with Honours in Genetics from the University of Edinburgh (UK). Currently, she received her PhD in Gene Technology at the University of Tartu. She is BBMRI-ERIC Common Service ELSI representative for the Estonian national node. Liis Letsalu has advanced her proficiency through the following: Research experience: 2010 Estonian Genome Center of the University of Tartu (EGCUT), Tartu, Estonia 2006, 2007 Tallinn University of Technology, Tallinn, Estonia Summer internships at the Department of Gene Technology, Professor Tõnis Timmusk’s Laboratory Clinical experience: 2016 Tartu University Hospital, Tallinn clinic, Estonia Genetic counseling intern at the genetics department 2008–2010 Sarah Lawrence College, Bronxville, NY Maimonides Clinical Center, Brooklyn, NY Genetic counseling in pediatrics and prenatal setting. Beth Israel Medical Center, New York, NY Genetic counseling in cancer setting. St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital, New York, NY Genetic counseling in pediatric and prenatal setting. Bronx-Lebanon Hospital, Bronx, NY Genetic counseling in prenatal setting. Other experience: 2016 University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia Member of the Research Ethics Committee 2015 BBMRI-ERIC, Common Service ELSI National representative for the Ethical, legal and societal issues working group. END OF DOCUMENT . -

Tallinn City Old Town CFMAEYTT2012

CFMAEYTT2012 Locations, hotel, distances and traffic (TRAM) Tram No. 1 Kopli - Kadriorg Tallinn University, Insti- Harbour tute of Fine Arts, Music Department Põhja puiestee Tallinn University Lai 13 Linnahall Peamaja / Main building “Terra” (T) Narva mnt 25 <-- Kopli Tallinn University “Mare” maja / building (M) Uus sadama 5 Balti jaam / Main railway ca. 10-15 min to walk station Park Inn by Radisson Mere puiestee L. Koidula Kadriorg Old town Tallinna Ülikooli Viru TRAM No. 3 Kadriorg Hobujaama c.a. 5-10 min to walk Old Town TRAM station ca. 20-25 min to walk ca. 10-15 min to walk Viru keskus / Viru Centre Theater No99 Jazzclub Tallinn City Tondi direction TRAM No. 3 Tondi-Kadriorg Location of the Tallinn University CAMPUS (”Mare” building Uus sadama 5 - keynotes, papers, lectures, workshops: APRIL 12) and the Tallinn University Institute of Fine Art, Music Department (keynotes, papers, lectures, workshops: APRIL 13). See also the location of the hotel of Park Inn by Radisson and the Theatre No99 Jazz club. Distances are short enough to walk. For longer distances can be used TRAM No. 1 (Kopli–Kadriorg) or TRAM No. 3 (Tondi–Kadriorg), see green and blue line in the map below). The frequency of TRAMs is tight and waiting time is minimal. Direct line: TRAM No. 1 (Kopli–Kadriorg) and TRAM 3 (Tondi–Kadriorg) TRAM 1 Linnahall – Tallinna Ülikooli (TLU Terra and Mare building) (ca. 10 min, longest station-distance) TRAM 1 Merepuiestee – Tallinna Ülikooli (ca. 4 min) TRAM 3 Viru - Tallinna Ülikooli (ca. 4 min) TRAM 1 and 3 Hobujaama - Tallinna Ülikooli (ca. -

Soviet Housing Construction in Tartu: the Era of Mass Construction (1960 - 1991)

University of Tartu Faculty of Science and Technology Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences Department of Geography Master thesis in human geography Soviet Housing Construction in Tartu: The Era of Mass Construction (1960 - 1991) Sille Sommer Supervisors: Michael Gentile, PhD Kadri Leetmaa, PhD Kaitsmisele lubatud: Juhendaja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Juhendaja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Osakonna juhataja: /allkiri, kuupäev/ Tartu 2012 Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Literature review ................................................................................................................................. 5 Housing development in the socialist states .................................................................................... 5 From World War I until the 1950s .............................................................................................. 5 From the 1950s until the collapse of the Soviet Union ............................................................... 6 Socio-economic differentiations in the socialist residential areas ................................................... 8 Different types of housing ......................................................................................................... 11 The housing estates in the socialist city .................................................................................... 13 Industrial control and priority sectors .......................................................................................... -

Uuring "Asustuse Arengu Suunamine Ja Toimepiirkondade Määramine"

Tartumaa maakonnaplaneering Asustuse arengu suunamine ja toimepiirkondade määramine Tellija: Tartu Maavalitsus Teostajad: Antti Roose ja Martin Gauk Tartu 2014 SISUKORD Sissejuhatus ............................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Tiheasulate piiritlemine Tartumaal ................................................................................................. 5 1.1. Ettepanekud asustuse suunamiseks ........................................................................................... 21 2. Tootmis-, äri- ja logistikaalad ........................................................................................................ 25 3. Tartumaa toimepiirkonnad ........................................................................................................... 28 Allikad .................................................................................................................................................... 35 Sissejuhatus Tartu maakonnaplaneering, mis kehtestati Tartu maavanema 23. aprilli 1999. a korraldusega nr 1537, on tingituna olulistest linnastumise ja teisalt ääremaastumise protsessidest aegunud ega saa olla lähtealuseks üldplaneeringute ja teiste asustuse arengut suunavate planeeringute koostamisele 15ne aasta möödudes. Planeeringuliselt on kõige põhimõttelisem Tartu ümbruse asustuse suunamine, sest sinna on tekkinud ja üsnagi vabalt arenemas täiesti uut tüüpi eeslinna-asustus. Uue Tartu maakonnaplaneeringu algatas -

Tours and Experiences

• HIGHLIGHTS OF THE BALTIC STATES IN 8 DAYS. An agenda of local best hits to spend a week in Baltic countries. Ask for 2020 guaranteed departure dates! • BALTICS AND SCANDINAVIA IN 10 DAYS. Discover the facinating diversity of the Baltics and Scandinavia. • BALTICS AND BELARUS IN DAYS. Get an insider’s view to all three Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia and spice up your travel experience with a visit to Belarus Baltics is an ideal place for soft adventure or walking holidays. You can really get a good sense of the diversity of natural beauty in our countries. You can walk the shoreline, wander through river valleys and forests, or just watch the landscape. The landscape is full of nature. There are wonderful paths in national parks and other areas that are under environmental protection. Allow yourself 8-14 days to walk and bus/train in between from Vilnius to Tallinn. NATIONAL PARKS & CITIES. Combination of National parks and Cities. Bike, Hike, Kayak, Walk and Taste Baltic States in this 13 day adventure. Day1. Vilnius. Arrival day. Day2. Vilnius walking tour. Day3. Hiking and kayaking in Aukštaitijos National Park. Day4. Free time in a homestead (sauna, bikes, walks and relax time). Day5. Road till Klaipėda port town. Walking in the city & Brewery visiting. Day6. Curonian Spit visiting (or biking half way). Day7. Rundale palace on a way to Riga. Day8. Riga day tour. Day9. Gauja National Park half-day walking trip. Day 10. Visiting Parnu on a way to Tallinn. Day 11. Tallinn walking tour. Day 12. Lahemaa bog shoes trekking tour with a picnic. -

Elukeskkonnaga Rahulolu Hindamise Metoodika Täiendusvõimalused Ja Andmete Kasutamine Säästva Arengu Suunamisel Uuringu Lõpparuanne

Elukeskkonnaga rahulolu hindamise metoodika täiendusvõimalused ja andmete kasutamine säästva arengu suunamisel Uuringu lõpparuanne Tellija: Rahandusministeerium, Kultuuriministeerium 30. aprill 2021 Uuring: Elukeskkonnaga rahulolu hindamise metoodika täiendusvõimalused ja andmete kasutamine säästva arengu suunamisel Uuringu autorid: Kaido Väljaots Keiti Kljavin Tõnu Hein Raul Kalvo Kristina Hiir Sille Sepp Anna-Kaisa Adamson Annela Pajumets Aima Allik Mart Kevin Põlluste Uuringu teostajad: HeiVäl OÜ / HeiVäl Consulting ™ Lai 30, 51005 Tartu www.heival.ee [email protected] +372 740 7124 Uuringu tellija: Rahandusministeerium, Kultuuriministeerium Uuring viidi läbi perioodil juuli 2020 – aprill 2021. Elukeskkonnaga rahulolu hindamise metoodika täiendusvõimalused ja andmete kasutamine säästva arengu suunamisel 2 Smart Analysis by HeiVäl Consulting / www.heival.ee SISUKORD 1. SISSEJUHATUS ................................................................................................................................... 4 Uuringu eesmärk ja lähteülesanne 4 2. ELUKESKKONNAGA RAHULOLU MÕISTE .................................................................................. 5 Elukeskkonna mõiste kujunEmise ülevaade 5 Erinevad mudelid elukeskkonna hindamiseks 6 Rahulolu hindamine 9 3. ELUKESKKONNAGA RAHULOLU MÕÕTMISE KOGEMUS TEISTES RIIKIDES .................. 13 Rahulolu mõõtmine välismaal 13 Austraalia kogemus. Linna elamisväärsuse indeks 13 Soome kogemus. SYKE uuring 16 ÜRO säästva arengu eesmärgid 20 4. STATISTIKAAMETI ARVAMUSKÜSITLUSE SEOSED .............................................................. -

Tallinna Kaubamaja Grupp As

TALLINNA KAUBAMAJA GRUPP AS Consolidated Interim Report for the Fourth quarter and 12 months of 2016 (unaudited) Tallinna Kaubamaja Grupp AS Table of contents MANAGEMENT REPORT ............................................................................................................................................ 4 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ........................................................................................................... 12 MANAGEMENT BOARD’S CONFIRMATION TO THE CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ....... 12 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION ....................................................................... 13 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF PROFIT OR LOSS AND OTHER COMPREHENSIVE INCOME ........ 14 CONSOLIDATED CASH FLOW STATEMENT ............................................................................................. 15 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN OWNERS’ EQUITY ...................................................... 16 NOTES TO THE CONSOLIDATED INTERIM ACCOUNTS ......................................................................... 17 Note 1. Accounting Principles Followed upon Preparation of the Consolidated Interim Accounts ........ 17 Note 2. Cash and cash equivalents ............................................................................................................... 18 Note 3. Trade and other receivables .............................................................................................................. 18 Note 4. Trade receivables ..............................................................................................................................