EXPERT REPORT Historical and Documentary Corroboration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Day Trips in British Columbia"

"Day Trips in British Columbia" Realizado por : Cityseeker 20 Ubicaciones indicadas Vancouver "City of Glass" The coastal city, Vancouver is the third-largest metropolitan area in Canada. A town was first founded on this site in 1867 when an entrepreneurial proprietor built a tavern along the water. Since then, towering skyscrapers have grown to dominate the skyline like glittering pinnacles of glass backed by mountains dusted with snow. The vast by Public Domain sprawl of Vancouver is centred around downtown's glimmering milieu of towers. From here unfurls a tapestry of neighbourhoods, each with a distinct character of its own. Kitsilano's beachfront is defined as much by its heritage homes as its pristine sand, Gastown hosts the city's indie culture. Wherever you go, you'll encounter a menagerie of sights to attest to Vancouver's culture-rich soul. Independent art galleries abound alongside swathes of public art, while Shakespearean shows intermingle with a blooming live music offer. There's plenty for outdoor enthusiasts as well, and this is one of the few places where you can ski down a mountain, go kayaking, hike through the forest and lounge on the beach in the same day. At the end of it all, there's a sumptuous array of international restaurants, home to some of North America's most authentic Asian cuisines, fantastic farm-to-table dining and soul-stirring seafood creations; not to mention an extensive list of top-notch craft breweries. All this and more makes Vancouver the crown jewel of British Columbia. +1 604 683 2000 (Tourist vancouver.ca/ [email protected] Vancouver, Vancouver BC Information) Victoria "A Cosmopolitan City With English Verve" Originally established as a fort for the Hudson's Bay Company back in 1843, Victoria was long known as the most British city in North America. -

Colonial Study of Indigenous Women Writers in Canada, the United States, and the Caribbean

ABSTRACT NATIVE AMERICAS: A TRANSNATIONAL AND (POST)COLONIAL STUDY OF INDIGENOUS WOMEN WRITERS IN CANADA, THE UNITED STATES, AND THE CARIBBEAN Elizabeth M. A. Lamszus, PhD Department of English Northern Illinois University, 2015 Dr. Kathleen J. Renk, Director In the current age of globalization, scholars have become interested in literary transnationalism, but the implications of transnationalism for American Indian studies have yet to be adequately explored. Although some anthologies and scholarly studies have begun to collect and examine texts from Canada and the United States together to ascertain what similarities exist between the different tribal groups, there has not yet been any significant collection of work that also includes fiction by indigenous people south of the U.S. border. I argue that ongoing colonization is the central link that binds these distinct groups together. Thus, drawing heavily on postcolonial literary theory, I isolate the role of displacement and mapping; language and storytelling; and cultural memory and female community in the fiction of women writers such as Leslie Marmon Silko, Pauline Melville, and Eden Robinson, among others. Their distinctive treatment of these common themes offers greater depth and complexity to postcolonial literature and theory, even though independence from settler colonizers has yet to occur. Similarly, the transnational study of these authors contributes to American Indian literature and theory, not by erasing what makes tribes distinct, but by offering a more diverse understanding of what it means to be a Native in the Americas in the face of ongoing colonization. NORTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY DEKALB, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2015 NATIVE AMERICAS: A TRANSNATIONAL AND (POST)COLONIAL STUDY OF INDIGENOUS WOMEN WRITERS IN CANADA, THE UNITED STATES, AND THE CARIBBEAN BY ELIZABETH M. -

National Energy Board L’Office National De L’Énergie

JOINT REVIEW PANEL FOR THE ENBRIDGE NORTHERN GATEWAY PROJECT COMMISSION D’EXAMEN CONJOINT DU PROJET ENBRIDGE NORTHERN GATEWAY Hearing Order OH-4-2011 Ordonnance d’audience OH-4-2011 Northern Gateway Pipelines Inc. Enbridge Northern Gateway Project Application of 27 May 2010 Demande de Northern Gateway Pipelines Inc. du 27 mai 2010 relative au projet Enbridge Northern Gateway VOLUME 126 Hearing held at Audience tenue à Sheraton Vancouver Wall Centre 1088 Burrard Street Vancouver, British Columbia January 16, 2013 Le 16 janvier 2013 International Reporting Inc. Ottawa, Ontario (613) 748-6043 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2013 © Sa Majesté du Chef du Canada 2013 as represented by the Minister of the Environment représentée par le Ministre de l’Environnement et and the National Energy Board l’Office national de l’énergie This publication is the recorded verbatim transcript Cette publication est un compte rendu textuel des and, as such, is taped and transcribed in either of the délibérations et, en tant que tel, est enregistrée et official languages, depending on the languages transcrite dans l’une ou l’autre des deux langues spoken by the participant at the public hearing. officielles, compte tenu de la langue utilisée par le participant à l’audience publique. Printed in Canada Imprimé au Canada HEARING /AUDIENCE OH-4-2011 IN THE MATTER OF an application filed by the Northern Gateway Pipelines Limited Partnership for a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity pursuant to section 52 of the National Energy Board Act, for authorization to construct and operate the Enbridge Northern Gateway Project. -

Thesis If You Will

Salmon Nation People. Place. An Invitation. SALMON NATION Salmon Nation is a place. It is home. Salmon Nation is also an idea: it is a nature state, as distinct from a nation state. Our idea is very simple. We live in a remarkable place. We are determined to do everything we can to improve social, financial and natural well-being here at home. We know we are not alone. Salmon Nation aims to inspire, enable and invest in regenerative develop- ment. A changing climate and failing systems demand new approaches to everything we do. We need to champion what works for people and place. To share what we learn in this place—and to do a lot more of it, over and over... Salmon Nation. People, place—and an invitation. We’d love you to join us on an adventure, charting new frontiers of human possibility, right here at home. ThIS essay, ThIS invitation, is made available under an open license. Feel free to distribute and disseminate, to react and reimagine. Open source projects are made available and are contributed to under licenses that, for the protection of contributors, make clear that the proj- ects and ideas are offered “as-is,” without warranty, and disclaiming liability for damages resulting from using the projects as they are. The same goes for this essay, or thesis if you will. Running an open-source project, like any human endeavour, involves uncertainty and trade-offs. We hope this essay helps to provoke excite- ment and enthusiasm for new ways of thinking and being in the world, but we acknowledge that it may include mistakes and that it cannot anticipate every situation. -

The English Prince

THE NOFfTH COAST DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS OF THE COAST DISTRICTS AND NORTHERN INTERIOR VOL. 1. No. 27. PORT SIMPSON. HRJTJSH COLUMBIA. SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 190* leaving the Beaver line and going to AN '• NCII.NT MINE. , the Yukon river this spring. LOCAL JOTTINGS I The clearing and developing of the Discovery « n Queen Chnrlotte Islands ' town of Prince Uupert ia reported to be "' 0ld shaft. Cut Your Tailoring: Bill OM4&4 goinjf on at a rspid rate. Over 500 acrea A moat ii i i eating And has been m;tde Win. Craigg, an employee of the have been cleared and graded on the on the COM; uf Queen Chnrlotte inlands in Half. North Coast Commercial Co., left last townsite and the dense volumes of amoke lately. A prospector Home time ago Monday for Port Essington. 'rorn clearing fires burning the brush, came across an old dump near the water M> n«n M™»Q „.„.„.,„( *u« /-.« shows that the job of clearing up is be- with a large tree about eighteen inches Mr. Don. Moore, manager of the Cas- , ., ^ ^ ^ Abo* ^ feet Cut out the coupon printed below, fill in your name and siar eannery, was in town on Friday. of tne main wharf along the water- Zohmh^oand tor Toms time and then address, mail it to us, and you will have taken the first great He left for the aouth per Amur. front is completed, and another 1000 'oolcai. "' '"' some l?ln? an<1 V step in the direction of clothes economy. .„ , hecun began to scratch away the IOOHO refuse De un Our easy self-measurement blank gives clear, explicit Miss IMM was a passenger by the « - . -

The Birth of the Great Bear Rainforest: Conservation Science and Environmental Politics on British Columbia's Central and North Coast

THE BIRTH OF THE GREAT BEAR RAINFOREST: CONSERVATION SCIENCE AND ENVIRONMENTAL POLITICS ON BRITISH COLUMBIA'S CENTRAL AND NORTH COAST by JESSICA ANNE DEMPSEY B.Sc, The University of Victoria, 2002 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Geography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA July 2006 © Jessica Anne Dempsey, 2006 11 Abstract This thesis examines the birth of the Great Bear Rainforest, a large tract of temperate rainforest located on British Columbia's central and north coasts. While the Great Bear Rainforest emerges through many intersecting forces, in this study I focus on the contributions of conservation science asking: how did conservation biology and related sciences help constitute a particular of place, a particular kind of forest, and a particular approach to biodiversity politics? In pursuit of these questions, I analyzed several scientific studies of this place completed in the 1990s and conducted interviews with people involved in the environmental politics of the Great Bear Rainforest. My research conclusions show that conservation science played an influential role in shaping the Great Bear Rainforest as a rare, endangered temperate rainforest in desperate need of protection, an identity that counters the entrenched industrial-state geographies found in British Columbia's forests. With the help of science studies theorists like Bruno Latour and Donna Haraway, I argue that these conservation studies are based upon purification epistemologies, where nature - in this case, the temperate rainforest - is separated out as an entity to be explained on its own and ultimately 'saved' through science. -

The Tsimshian Homeland: an Ancient Cultural Landscape

THE TSIMSHIAN HOMELAND: AN ANCIENT CULTURAL LANDSCAPE By KEN DOWNS Integrated Studies Project submitted to Dr. Leslie Main Johnson in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Integrated Studies Athabasca, Alberta February, 2006 The Tsimshian Homeland: An Ancient Cultural Landscape Questioning the “Pristine Myth” in Northwestern British Columbia What are the needs of all these plants? This is the critical question for us. Rest, protection, appreciation and respect are a few of the values we need to give these generous fellow passengers through time. K”ii7lljuus (Barbara Wilson 2004:216) Ksan (Skeena River) downstream from Kitsumkalum looking toward Terrace Master of Integrated Studies Final Project – Athabasca University Submitted to Dr. Leslie Main Johnson – February 25, 2006 – Ken Downs Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………….... … 4 Tsimshian Landscape ………………………………………………… 6 Tsimshian Archaeology………………………………......................... 12 Tsimshian: “Complex Hunter-Gatherers”? ............................................ 15 Investigations of Tsimshian Agriculture – Field Research …………….. 17 Results of Fieldwork (2003-2005) ……………………………………… 19 Kalum Canyon Sites …………………………………………………….. 36 Adawx: Oral Histories of the Canyon …………………………………… 45 Canyon Tsimshian Plant Resources and Management ………………….. 48 Significant Plants at Kalum Canyon …………………………………….. 50 Kalum Canyon Agro-Ecosystems ………………………………………… 66 Conclusions ……………………………………………………………….. 69 Further Research …………………………………………………………… 74 Acknowledgements -

The Fur Trade Era, 1770S–1849

Great Bear Rainforest The Fur Trade Era, 1770s–1849 The Fur Trade Era, 1770s–1849 The lives of First Nations people were irrevocably changed from the time the first European visitors came to their shores. The arrival of Captain Cook heralded the era of the fur trade and the first wave of newcomers into the future British Columbia who came from two directions in search of lucrative pelts. First came the sailors by ship across the Pacific Ocean in pursuit of sea otter, then soon after came the fort builders who crossed the continent from the east by canoe. These traders initiated an intense period of interaction between First Nations and European newcomers, lasting from the 1780s to the formation of the colony of Vancouver Island in 1849, when the business of trade was the main concern of both parties. During this era, the newcomers depended on First Nations communities not only for furs, but also for services such as guiding, carrying mail, and most importantly, supplying much of the food they required for daily survival. First Nations communities incorporated the newcomers into the fabric of their lives, utilizing the new trade goods in ways which enhanced their societies, such as using iron to replace stone axes and guns to augment the bow and arrow. These enhancements, however, came at a terrible cost, for while the fur traders brought iron and guns, they also brought unknown diseases which resulted in massive depopulation of First Nations communities. European Expansion The northwest region of North America was one of the last areas of the globe to feel the advance of European colonialism. -

Mutiny on the Beaver 15 Mutiny on the Beaver: Law and Authority in the Fur Trade Navy, 1835-1840

Mutiny on the Beaver 15 Mutiny on the Beaver: Law and Authority in the Fur Trade Navy, 1835-1840 Hamar Foster* ... I decided on leaving them to be dealt with through the slow process of the law, as being in the end more severe than a summary infliction." L INTRODUCTION IT IS CONVENTIONAL TO SEEK THE HISTORICAL ROOTS of British Columbia labour in the colonial era, that is to say, beginning in 1849 or thereabouts. That was when Britain established Vancouver Island, its first colony on the North Pacific coast, and granted the Hudson's 1991 CanLIIDocs 164 Bay Company fee simple title on the condition that they bring out settlers.' It is a good place to begin, because the first batch of colonists were not primarily gentlemen farmers or officials but coal miners and agricultural labourers, and neither the Company nor Vancouver Island lived up to their expectations.' The miners were Scots, brought in to help the Hudson's Bay Company diversify and exploit new resources in the face of declining fur trade profits, but * Hamar Foster is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Law, University of Victoria, teaching a variety of subjects, including legal history. He has published widely in the field of Canadian legal history, as well as in other areas of law. James Douglas, Reporting to the Governor and Committee on the "Mutiny of the Beaver Crew, 1838", Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Hudson's Bay Company Archives [hereinafter HBCA] B. 223/6/21. ' In what follows the Hudson's Bay Company ("IHC') will be referred to as "they," etc., rather than "it". -

Northwest Coast Archaeology

ANTH 442/542 - Northwest Coast Archaeology COURSE DESCRIPTION This course examines the more than 12,000 year old archaeological record of the Northwest Coast of North America, the culture area extending from southeast Alaska to coastal British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and northern California. This region has fascinated anthropologists for almost 150 years because its indigenous peoples have developed distinctive cultures based on fishing, hunting, and gathering economies. We begin by establishing the ecological and ethnographic background for the region, and then study how these have shaped archaeologists' ideas about the past. We study the contents of sites and consider the relationship between data, interpretation, and theory. Throughout the term, we discuss the dynamics of contact and colonialism and how these have impacted understandings of the recent and more distant pasts of these societies. This course will prepare you to understand and evaluate Northwest Coast archaeological news within the context of different jurisdictions. You will also have the opportunity to visit some archaeological sites on the Oregon coast. I hope the course will prepare you for a lifetime of appreciating Northwest Coast archaeology. WHERE AND WHEN Class: 10-11:50 am, Monday & Wednesday in Room 204 Condon Hall. Instructor: Dr. Moss Office hours: after class until 12:30 pm, and on Friday, 1:30-3:00 pm or by appointment 327 Condon, 346-6076; [email protected] REQUIRED READING: Moss, Madonna L. 2011 Northwest Coast: Archaeology as Deep History. SAA Press, Washington, D.C. All journal articles/book chapters in the “Course Readings” Module on Canvas. Please note that all royalties from the sale of this book go to the Native American Scholarship Fund of the Society for American Archaeology. -

FORREST, Charles PARISH: St

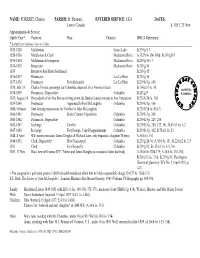

NAME: FORREST, Charles PARISH: St. Edouard, ENTERED SERVICE: 1824 DATES: Lower Canada d. 1851, 23 Nov. Appointments & Service Outfit Year*: Position: Post: District: HBCA Reference: *An Outfit year ran from 1 June to 31 May 1825-1828 Middleman Island Lake B.239/g/5-7 1828-1830 Middleman & Clerk Mackenzie River A.32/29 fo.106-106d; B.239/g/8-9 1830-1834 Middleman & Interpreter Mackenzie River B.239/g/10-13 1834-1835 Interpreter Mackenzie River B.239/g/14 1835 Retired to Red River Settlement B.239/g/15 1836-1837 Postmaster Lac La Pluie B.239/g/16 1837-1838 Postmaster Fort Alexander Lac La Pluie B.239/k/3 p. 160 1838, July 24 Charles Forrest, passenger for Columbia, departed from Norway House B.154/a/31 fo. 9d ARCHIVES 1838-1839 Postmaster, Disposable+ Columbia B.223/g/5 WINNIPEG 1839, August 16 Proceeded to Fort Nez Perces to bring down the Snake Country returns to Fort Vancouver B.223/b/24 fo. 39d 1839-1840 Postmaster Appointed to Fort McLoughlin Columbia B.239/k/3 p. 186 1840, February Sent farming instructions for Cowlitz by John McLoughlin B.223/b/24 fo. 63d-71 1840-1841 Postmaster Snake Country Expedition Columbia B.239/k/3 p. 206 1841-1842 Postmaster, Disposable+ Columbia B.239/k/3 p. 229, 258 1842-1847 In charge Cowlitz Columbia B.239/k/3 p. 280, 332, 361; B.47/z/1 fo. 1-2 1847-1848 In charge Fort George, Cape Disappointment Columbia B.239/k/3 p. -

^Mllm^Frmum the S.S

^MllM^frMUm THE S.S. PRINCE GEORGE ACCOMMODATION AND EQUIPMENT The luxurious, new Prince George—5800 tons, length 350 feet, speed 18 knots—is of the very latest design and especially built for Pacific Coast service to Alaska. It has accommodation for 260 passengers and its comfortable staterooms are the last word in convenience and smartness. Staterooms are equipped with outlet for electric razors. In all cabins the fold-away beds disappear into the wall in daytime. In addition it is outfitted with the most modern devices for the utmost safety in navigation. The Prince George has seven decks and eight, spacious public rooms, including clubrooms and sitting rooms. Nothing has been overlooked in providing for the com fort of the passengers on the ten day cruise from Vancouver, B.C,, to Skagway, Alaska, and return. This Booklet Describes, in a concise manner, the water ways traversed and the ports of call made by Canadian National Steamer, S.S. "Prince George." Explains the necessary official formalities in passing from one country to another, that, with understanding, they may prove less irksome. Anticipates the vacationist's queries while enroute on one of the world's most scenic waterways. The Inside Pas sage to Alaska. If an extra copy is required to pass on to some friend, just drop a note to the nearest Canadian National representative listed on page 34. // you wish he will mail it for you. TABLE OF CONTENTS Embarkation at Vancouver 7 Checking Passengers on and off Steamer- 14 Descriptive Notes 14 to 31 Dining Saloon 8 Distances Between Vancouver—Skagway„ 6 Immigration and Customs Regulations 12-13 List of Canadian National Ticket Offices 34 Service Suggestions 8-10 S.S.