Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D* in Th© University of London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Understanding of Maya: the Philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva

An understanding of Maya: The philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva Department of Religion studies Theology University of Pretoria By: John Whitehead 12083802 Supervisor: Dr M Sukdaven 2019 Declaration Declaration of Plagiarism 1. I understand what plagiarism means and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this Dissertation is my own work. 3. I did not make use of another student’s previous work and I submit this as my own words. 4. I did not allow anyone to copy this work with the intention of presenting it as their own work. I, John Derrick Whitehead hereby declare that the following Dissertation is my own work and that I duly recognized and listed all sources for this study. Date: 3 December 2019 Student number: u12083802 __________________________ 2 Foreword I started my MTh and was unsure of a topic to cover. I knew that Hinduism was the religion I was interested in. Dr. Sukdaven suggested that I embark on the study of the concept of Maya. Although this concept provided a challenge for me and my faith, I wish to thank Dr. Sukdaven for giving me the opportunity to cover such a deep philosophical concept in Hinduism. This concept Maya is deeper than one expects and has broaden and enlightened my mind. Even though this was a difficult theme to cover it did however, give me a clearer understanding of how the world is seen in Hinduism. 3 List of Abbreviations AD Anno Domini BC Before Christ BCE Before Common Era BS Brahmasutra Upanishad BSB Brahmasutra Upanishad with commentary of Sankara BU Brhadaranyaka Upanishad with commentary of Sankara CE Common Era EW Emperical World GB Gitabhasya of Shankara GK Gaudapada Karikas Rg Rig Veda SBH Sribhasya of Ramanuja Svet. -

The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita

THE SACRED BOOKS OFTHEEAST Volume 8 SACRED BOOKS OF THE EAST EDITOR: F. Max Muller These volumes of the Sacred Books of the East Series include translations of all the most important works of the seven non Christian religions. These have exercised a profound innuence on the civilizations of the continent of Asia. The Vedic Brahmanic System claims 21 volumes, Buddhism 10, and Jainism 2;8 volumes comprise Sacred Books of the Parsees; 2 volumes represent Islam; and 6 the two main indigenous systems of China. thus placing the historical and comparative study of religions on a solid foundation. VOLUMES 1,15. TilE UPANISADS: in 2 Vols. F. Max Muller 2,14. THE SACRED LAWS OF THE AR VAS: in 2 vols. Georg Buhler 3,16,27,28,39,40. THE SACRED BOOKS OF CHINA: In 6 Vols. James Legge 4,23,31. The ZEND-AVESTA: in 3 Vols. James Darmesleler & L.H. Mills 5, 18,24,37,47. PHALVI TEXTS: in 5 Vall. E. W. West 6,9. THE QUR' AN: in 2 Vols. E. H. Palmer 7. The INSTITUTES OF VISNU: J.Jolly R. THE BHAGA VADGITAwith lhe Sanalsujllliya and the Anugilii: K.T. Telang 10. THE DHAMMAPADA: F. Max Muller SUTTA-NIPATA: V. Fausbiill 1 I. BUDDHIST SUTTAS: T.W. Rhys Davids 12,26,41,43,44. VINAYA TEXTS: in 3 Vols. T.W. Rhys Davids & II. Oldenberg 19. THE FO·SHO-HING·TSANG·KING: Samuel Beal 21. THE SADDHARMA-PUM>ARlKA or TilE LOTUS OF THE TRUE LAWS: /I. Kern 22,45. lAINA SUTRAS: in 2 Vols. -

The Bhagavad Gita: Ancient Poem, Modern Readers

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the current Summer Seminars and Institutes guidelines, which reflect the most recent information and instructions, at https://www.neh.gov/program/summer-seminars-and-institutes-higher-education-faculty Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Education Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: The Bhagavad Gita: Ancient Poem, Modern Readers Institution: Bard College Project Director: Richard Davis Grant Program: Summer Seminars and Institutes (Seminar for Higher Education Faculty) 400 7th Street, SW, Washington, DC 20024 P 202.606.8500 F 202.606.8394 [email protected] www.neh.gov The Bhagavad Gita: Ancient Poem, Modern Readers Summer Seminar for College and University Teachers Director: Richard H. Davis, Bard College Table of Contents I. Table of Contents ………………………………………………………………………. i II. Narrative Description …………………………………………………………………. 1 A. Intellectual rationale …………………………………………………………... 1 B. Program of study ……………………………………………………………… 7 C. Project faculty and staff ……………………………………………………… 12 D. -

Bhaga Vad-Gita

THE HISTORICAL GAME-CHANGES IN THE PHILOSOPHY OF DEVOTION AND CASTE AS USED AND MISUSED BY THE BHAGA VAD-GITA BY - ,<" DR. THILAGAVATHI CHANDULAL BA, MBBS (Madras), MRCOG, FRCOG (UK), MDiv. (Can) TOWARDS THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MA IN PHILOSOPHY TO THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES BROCK UNIVERSITY ST. CATHARINES, ONTARIO, CANADA, L2S 2Al © 5 JANUARY 2011 11 THREE EPIGRAPHS ON THE ATHLETE OF THE SPffiIT Majority of us are born, eddy around, die only to glut the grave. Some - begin the quest, 'eddy around, but at the first difficulty, getting frightened, regress to the non-quest inertia. A few set out, but a very small number make it to the mountain top. Mathew Arnold, Rugby Chapel Among thousands of men scarcely one strives for perfection, and even among these who strive and succeed, scarcely one knows Me in truth. The Bhagavad-Gita 7. 3 Do you not know that in a race the runners all compete, but only one receives the prize? Run in such a way that you may win it. Athletes exercise self-control in all things; they do it to receive a perishable wreath, but we an imperishable one. St. Paul, First Letter to the Corinthian Church, 9.24-25 111 Acknowledging my goodly, heritage Father, Savarimuthu's world-class expertise in Theology: Christian, Lutheran and Hindu Mother, Annapooranam, who exemplified Christian bhakti and nlJrtured me in it ~ Aunt, Kamalam, who founded Tamil grammar and literature in me in my pre-teen years Daughter, Rachel, who has always been supportive of my education Grandchildren, Charisa and Chara, who love and admire me All my teachers all my years iv CONTENTS Abstract v Preface VI Tables, Lists, Abbreviations IX Introduction to bhakti X Chronological Table XVI Etymology of bhakti (Sanskrit), Grace (English), Anbu (Tamil), Agape (Greek) XVll Origin and Growth of bhakti xx Agape (love) XXI Chapter 1: Game-Changes in bhakti History: 1 Vedic devotion Upanishadic devotion Upanishads and bhakti The Epics and bhakti The Origin of bhakti . -

The Mahabharata and the Sa,,,,Hitas of Caraka and Susruta

,,., BRILL Asian Medicine 3 (2007) 85-102 www.brill.nl/asme Narrativity and Empiricism in Classical Indian Accounts of Birth and Death: The Mahabharata and the sa,,,,hitas of Caraka and Susruta Frederick M. Smith Abstract This paper will address the relationship between the Mahabharata's representation of the physical processes of birth and death and similar material found in the classical ayurvedic texts of Caraka and Susruta, which are roughly contemporaneous with the Sanskrit epic (second century BCE second century CE). My primary source in the Mahabharata (MBh) is the Anugita, the second, and lesser known, dialogue between Kr~1,1a and Arjuna. This 'subsidiary Gita is situated in the fourteenth book (parvan) of the epic, the Afvamedhika parvan, which ostensibly deals with the horse sacrifice (afvamedha) performed by the victorious king Yudhi~rhira after the conclusion of the great war. The relevant chapters of the Anugita (MBh 14.17-18) contain fascinating and practically unknown material on the physical processes of birth and death, on embryology, and on physical dissolution. I will explicate this material, and then compare it with selected passages from the Caraka-Sarrihita and the Sufruta-Sarrihita. I shall then ask why, given considerable evi dence for intertextuality between the MBh and the ayurvedic compendia, the classical medical texts did not include this interesting material and why the Mahabharata did. In exploring this question, I must inquire into the scientific, or at least empirical, principles utilised in the medical texts that would force their authors to exclude the MBh material they probably knew well, in order to frame a particular kind of discourse. -

Spiritual Features of War-Related Moral Injury: a Primer for Clinicians

Spirituality in Clinical Practice In the public domain 2017, Vol. 4, No. 4, 249–261 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/scp0000140 Spiritual Features of War-Related Moral Injury: A Primer for Clinicians Jennifer H. Wortmann Ethan Eisen Durham VA Medical Center, Durham, North VA Long Beach Healthcare System, Carolina, and Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Long Beach, California Research, Education, and Clinical Centers, Durham, North Carolina Carol Hundert Alexander H. Jordan Loyola University Chicago McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts, and Harvard Medical School Mark W. Smith William P. Nash Naval Chaplaincy School and Center Headquarters, United States Marine Corps, Arlington, Virginia Brett T. Litz VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston, Massachusetts, and Boston University School of Medicine Warzone experiences that violate deeply held moral beliefs and expectations may lead to moral injury and associated spiritual distress (Litz et al., 2009). Helping morally injured war veterans who are grappling with spiritual or religious issues is part of multicultural competence (Vieten et al., 2013) and falls within the scope of practice of mental health clinicians. Moreover, practicing clinicians report that they lack adequate knowledge of the diverse spiritual and religious backgrounds of their clients and when to seek consultation from and collaborate with spiritual/religious teachers (Vieten et al., 2016). We argue that optimal assessment and treatment of psychically traumatized military personnel and veterans requires an understanding of the idioms and -

Hinduism Is Not a Religion but a Way of Life- Tile Beauty of Hinduism Lies in Its All Embracing Ir.Dusivei\Ess

Hinduism is not a religion but a way of Life- Tile beauty of Hinduism lies in its all embracing ir.dusivei\ess. Hinduism tells every one to worship God according to his own faith or dimma, and so it lives si peace wilh all the religions. Its freedom from dogma makes a forcible appeal to me inasmuch as i I gi ves the volaryihe largest scope for seJf-expressioiv Non-violence is common to all religions, but it has found the highest expression and application in Hinduism. Hinduism is a growlh of ages. Hinduism abhors stagnation. This boo k, a tollec tioi i of extrat ts from Gan dhij i's w ri tings expounds the essence of Hinduism:.' Rs 45,00 3S^M Wfi-8i-2^7-0y27-7 NATIONAL BOOK TRUST, INDIA What is Hinduism? MAHATMA GANDHI On behalf of Indian Council of Historical Research National Book Trust, India Contents Preface vii 1. What is Hinduism? 1 2. Is there Satan in Hinduism? 2 3. Why I am a Hindu? 3 4. Hinduism 6 5. Sanatana Hindu 11 6. Some Objections Answered 12 7. The Congress and After 15 8. My Mission 17 9. Hindu-Muslim Tension: 19 Its Causes and Cure 10. What may Hindus do? 21 11. Hinduism of Today 24 12. The Hydra-headed Monster 28 13. Tulsidas 30 14. Weekly Letter (Other Questions) 33 15. Weekly Letter (A talk with 36 Rao Bahadur Rajah) 16. Weekly Utter (The Golden Key) 37 17. The Haripad Speech 41 18. From the Kottayam Speech 45 19. Yajna or Sacrifice 48 20. -

Vier Philosophische Texte Des Mahâbhâratam

462 NOTICES OF BOOKS. difficult and ohscure period will be as illuminating and full of interest as the pages that have gone before. A word must be added in praise of the frontispiece, which is an excellent reproduction of a miniature from a Persian manuscript in the India Office Library. The manuscript formerly belonged to Shah Isma'il the Safawid, and the scene depicted shows a Persian poet offering an ode to a Mongol prince or governor. The six Mongols with their broad stolid faces and broad-brimmed hats make a striking contrast to the refined and expressive countenance of the Persian, who is further distinguished by his turban and long beard. R. A. N. VIKR PHILOSOPHISCHE TEXTE DES MAHABHARATAM. Trans- lated by Dr. P. DEDSSEN. (Leipzig, 1906.) This translationof the Sanatsujataparvan,the Bhagavadgita, the Moksadharma, and the Anugita is intended by Professor Deussen to serve as a basis for the third part of his great History of Philosophy, just as his translation of theUpanisads formed the groundwork of the second part of his History. The thanks of all students of Indian philosophy are due to Professor Deussen and to his pupils, Dr. Otto Strauss and Dr. P. E. Dumont, for their laborious work, which has rendered easily accessible these four great texts. The translation, so far as we have compared it with the original, is executed with great care and accuracy, and the number of passages in which a different rendering might be preferable is, considering the vague and ambiguous character of much, of the Sanski'it text, very small. -

Introduction to Vedic Knowledge

Introduction to Vedic Knowledge Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2012 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved. Title ID: 4165735 ISBN-13: 978-1482500363 ISBN-10: 148250036 : Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center +91 94373 00906 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com http://www.facebook.com/pages/Parama-Karuna-Devi/513845615303209 http://www.facebook.com/JagannathaVallabhaVedicResearchCenter © 2011 PAVAN PAVAN House Siddha Mahavira patana, Puri 752002 Orissa Introduction to Vedic Knowledge TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Perspectives of study The perception of Vedic culture in western history Study of vedic scriptures in Indian history 2. The Vedic texts When, how and by whom the Vedas were written The four original Vedas - Samhitas, Brahmanas, Aranyakas Upanishads 3. The fifth Veda: the epic poems Mahabharata and Bhagavad gita Ramayana and Yoga Vasistha Puranas 4. The secondary Vedas Vedangas and Upavedas Vedanta sutra Agamas and Tantra Conclusion 3 Parama Karuna Devi 4 Introduction to Vedic Knowledge The perception of Vedic culture in western history This publication originates from the need to present in a simple, clear, objective and exhaustive way, the basic information about the original Vedic knowledge, that in the course of the centuries has often been confused by colonialist propaganda, through the writings of indologists belonging to the euro-centric Christian academic system (that were bent on refuting and demolishing the vedic scriptures rather than presenting them in a positive way) and through the cultural superimposition suffered by sincere students who only had access to very indirect material, already carefully chosen and filtered by professors or commentators that were afflicted by negative prejudice. -

Bhagavad-Gîtâ

Bhagavad-Gîtâ Compiled by: Trisha Lamb Last Revised: April 27, 2006 © International Association of Yoga Therapists (IAYT) 2005 International Association of Yoga Therapists P.O. Box 2513 • Prescott • AZ 86302 • Phone: 928-541-0004 E-mail: [email protected] • URL: www.iayt.org The contents of this bibliography do not provide medical advice and should not be so interpreted. Before beginning any exercise program, see your physician for clearance. Adidevananda, Swami, trans. Sri Ramanuja Gita Bhasya. Vedanta Press, 1992. From the viewpoint of Bhakti-Yoga. Agarwal, S. P. Lokasamgraha and ahimsa in the Bhagavad Gita. Journal of Dharma, Jul- Sep 1991, 16(3):255-268. Alexander, P. C. Universal message of the Bhagavadgita. Prabuddha Bharata, Sep 2002, 106:26-29. Antonov, V., ed. Bhagavad-Gita (the Lord’s Song). Moscow, 1991. [In Russian]. ___________. Three aspects of Krishna’s teaching. Trans. by T. Danilevich. Article available online: http://www.swami-center.org/en/text/Three_aspects.html. Arjunwadkar, K. S. Philosophy on the battlefield: The Bhagavad-Gita v. Jnana-Yoga: The yoga of spiritual knowledge. Yoga & Health, Jun 2002, pp. 29-31. Arnold, Sir Edwin, trans. The Song Celestial or Bhagavad-Gita (1885). Kessinger Publising, 1998. Theosophical University Press Electronic Edition available for download online: http://www.theosophy-nw.org/theosnw/ctg/bhaggita.htm. Also available at: http://www.yogamovement.com/texts/gita.html. Ghandi’s favorite English translation of the Gita. Atulananda, Swami. Reflections on the Bhagavadgita. Prabuddha Bharata, Jun 2003, pp. 29-37. ___________. Reflections on the Bhagavadgita. Prabuddha Bharata, Jul 2003, pp. 18- 29. Aurobindo, Sri. Essays on the Gita. -

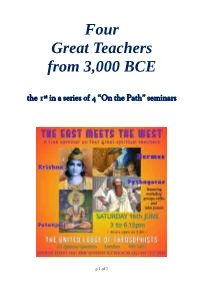

Four Great Teachers from 3,000 BCE the 1St in a Series of 4 “On the Path” Seminars

Four Great Teachers from 3,000 BCE the 1st in a series of 4 “On the Path” seminars p 1 of 7 Krishna Mystical Teacher of Ancient India When writing about the Yadavas or the “Lunar Dynasty” of ancient India, H. P. Blavatsky adds that “It was under Krishna – certainly no mythical personage – that the kingdom of Dwaraka in Guzerat was established; and also after the death of Krishna (3102 B.C.) that all the Yadavas present in the city perished, when it was submerged by the ocean.” (The Theosophical Glossary p. 374) “. the beginning of the Kali Yuga [was] at the death of Krishna, the bright “Sun-god,” the once living hero and reformer” (HPB, The Secret Doctrine Vol. 1, p. xliii, Introductory) The Kali Yuga is the name for the Dark or Black Age in which we presently live. Krishna is most commonly connected with the scripture known as the Bhagavad Gita (literally “The Lord’s Song” or “Song of God”) which is 18 short chapters from the epic of the Mahabharata. The Gita “contains a dialogue wherein Krishna – the “Charioteer” – and Arjuna, his Chela, have a discussion upon the highest spiritual philosophy. The work is pre-eminently occult or esoteric” (HPB, “Theosophical Glossary” p. 56) and it “tends to impress upon the individual two things: first, selflessness, and second, action; the studying of and living by it will arouse the belief that there is but one Spirit and not several; that we cannot live for ourselves alone, but must come to realize that there is no such thing as separateness, and no possibility of escaping from the collective Karma of the race to which one belongs, and then, that we must think and act in accordance with such belief,” (William Q. -

'CHAKRA' the Symbol of Dharma

‘CHAKRA’ The Symbol of Dharma By PROFESSOR B.R. SHARMA Transaction no. 51 INDIAN INSTITUTE OF WORLD CULTURE Bangalore-560 004 TRANSACTIONS Many valuable lectures are given, papers read and discussed, and oral reviews of outstanding books presented, at the Indian Institute of World Culture. These TRANSACTIONS represent some of these lectures and papers and are printed for wider dissemination in the cause of better intercultural understanding so important for world peace and human brotherhood. TRANSACTION NO 51 Professor B R Sharma who is U G C Professor at the Oriental Institute in Mysore was invited to deliver the Founder’s Day address at the Indian Institute of World Culture on August 19, 1978. The meeting was presided over by Smt. Sophia Wadia. Professor Sharma chose the concept of CHAKRA as a Symbol of Dharma in Brahminical literature—the Vedas. the Upanishads and the Mahabharata on one hand, and the Buddhistic scriptures in Pali and Sanskrit on the other. © 1980, Indian Institute of World Culture All Rights Reserved Printed by W. Q. Judge Press, 25, Rcsidency Road, Bangalore 560 025 and published by the Indian Institute of World Culture, Bangalore 560 004. Printed in India Chakra: The Symbol of Dharma By Professor B. R. SHARMA I In my address this evening I am making a brief survey of the concept of CHAKRA as a symbol of Dharma in Brahmanical literature,—the Vedas, the Upanishads and the Mahabharata, on one hand, and the Buddhistic scriptures in Pali and Sanskrit, on the other. I have excluded the Tantra literature from the purview of my survey for the reason that it is irrelevant to the theme of my address today.