My Reflections on Krishna & the Galaxy Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business SITUS Address Taxes Owed # 11828201655 PROPERTY HOLDING SERV TRUST 828 WABASH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28208 24.37 1 ROCK INVESTMENTS LLC

Business SITUS Address Taxes Owed # 11828201655 PROPERTY HOLDING SERV TRUST 828 WABASH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28208 24.37 1 ROCK INVESTMENTS LLC . 1101 BANNISTER PL CHARLOTTE NC 28213 510.98 1 STOP MAIL SHOP 8206 PROVIDENCE RD CHARLOTTE NC 28277 86.92 1021 ALLEN LLC . 1021 ALLEN ST CHARLOTTE NC 28205 419.39 1060 CREATIVE INC 801 CLANTON RD CHARLOTTE NC 28217 347.12 112 AUTO ELECTRIC 210 DELBURG ST DAVIDSON NC 28036 45.32 1209 FONTANA AVE LLC . FONTANA AV CHARLOTTE 22.01 1213 W MOREHEAD STREET GP LLC . 1207 W MOREHEAD ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 2896.87 1213 W MOREHEAD STREET GP LLC . 1201 W MOREHEAD ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 6942.12 1233 MOREHEAD LLC . 630 402 CALVERT ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 1753.48 1431 E INDEPENDENCE BLVD LLC . 1431 E INDEPENDENCE BV CHARLOTTE NC 28205 1352.65 160 DEVELOPMENT GROUP LLC . HUNTING BIRDS LN MECKLENBURG 444.12 160 DEVELOPMENT GROUP LLC . STEELE CREEK RD MECKLENBURG 2229.49 1787 JAMESTON DR LLC . 1787 JAMESTON DR CHARLOTTE NC 28209 3494.88 1801 COMMONWEALTH LLC . 1801 COMMONWEALTH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28205 9819.32 1961 RUNNYMEDE LLC . 5419 BEAM LAKE DR UNINCORPORATED 958.87 1ST METROPOLITAN MORTGAGE SUITE 333 3420 TORINGDON WY CHARLOTTE NC 28277 15.31 2 THE MAX SALON 10223 E UNIVERSITY CITY BV CHARLOTTE NC 28262 269.96 201 SOUTH TRYON OWNER LLC 201 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28202 396.11 201 SOUTH TRYON OWNER LLC 237 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28202 49.80 2010 TRYON REAL ESTATE LLC . 2010 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28203 3491.48 208 WONDERWOOD TREE PRESERVATION HO . -

An Understanding of Maya: the Philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva

An understanding of Maya: The philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva Department of Religion studies Theology University of Pretoria By: John Whitehead 12083802 Supervisor: Dr M Sukdaven 2019 Declaration Declaration of Plagiarism 1. I understand what plagiarism means and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this Dissertation is my own work. 3. I did not make use of another student’s previous work and I submit this as my own words. 4. I did not allow anyone to copy this work with the intention of presenting it as their own work. I, John Derrick Whitehead hereby declare that the following Dissertation is my own work and that I duly recognized and listed all sources for this study. Date: 3 December 2019 Student number: u12083802 __________________________ 2 Foreword I started my MTh and was unsure of a topic to cover. I knew that Hinduism was the religion I was interested in. Dr. Sukdaven suggested that I embark on the study of the concept of Maya. Although this concept provided a challenge for me and my faith, I wish to thank Dr. Sukdaven for giving me the opportunity to cover such a deep philosophical concept in Hinduism. This concept Maya is deeper than one expects and has broaden and enlightened my mind. Even though this was a difficult theme to cover it did however, give me a clearer understanding of how the world is seen in Hinduism. 3 List of Abbreviations AD Anno Domini BC Before Christ BCE Before Common Era BS Brahmasutra Upanishad BSB Brahmasutra Upanishad with commentary of Sankara BU Brhadaranyaka Upanishad with commentary of Sankara CE Common Era EW Emperical World GB Gitabhasya of Shankara GK Gaudapada Karikas Rg Rig Veda SBH Sribhasya of Ramanuja Svet. -

Geologic Map of the Victoria Quadrangle (H02), Mercury

H01 - Borealis Geologic Map of the Victoria Quadrangle (H02), Mercury 60° Geologic Units Borea 65° Smooth plains material 1 1 2 3 4 1,5 sp H05 - Hokusai H04 - Raditladi H03 - Shakespeare H02 - Victoria Smooth and sparsely cratered planar surfaces confined to pools found within crater materials. Galluzzi V. , Guzzetta L. , Ferranti L. , Di Achille G. , Rothery D. A. , Palumbo P. 30° Apollonia Liguria Caduceata Aurora Smooth plains material–northern spn Smooth and sparsely cratered planar surfaces confined to the high-northern latitudes. 1 INAF, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Rome, Italy; 22.5° Intermediate plains material 2 H10 - Derain H09 - Eminescu H08 - Tolstoj H07 - Beethoven H06 - Kuiper imp DiSTAR, Università degli Studi di Napoli "Federico II", Naples, Italy; 0° Pieria Solitudo Criophori Phoethontas Solitudo Lycaonis Tricrena Smooth undulating to planar surfaces, more densely cratered than the smooth plains. 3 INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Teramo, Teramo, Italy; -22.5° Intercrater plains material 4 72° 144° 216° 288° icp 2 Department of Physical Sciences, The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK; ° Rough or gently rolling, densely cratered surfaces, encompassing also distal crater materials. 70 60 H14 - Debussy H13 - Neruda H12 - Michelangelo H11 - Discovery ° 5 3 270° 300° 330° 0° 30° spn Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie, Università degli Studi di Napoli "Parthenope", Naples, Italy. Cyllene Solitudo Persephones Solitudo Promethei Solitudo Hermae -30° Trismegisti -65° 90° 270° Crater Materials icp H15 - Bach Australia Crater material–well preserved cfs -60° c3 180° Fresh craters with a sharp rim, textured ejecta blanket and pristine or sparsely cratered floor. 2 1:3,000,000 ° c2 80° 350 Crater material–degraded c2 spn M c3 Degraded craters with a subdued rim and a moderately cratered smooth to hummocky floor. -

In Search of Vyāsa: the Use of Greco-Roman Sources in Book 4 of the Mahābhārata

1 IN SEARCH OF VYĀSA: THE USE OF GRECO-ROMAN SOURCES IN BOOK 4 OF THE MAHĀBHĀRATA F WULFF ALONSO 2 © Fernando WULFF ALONSO In Search of Vyāsa: The Use of Greco-Roman Sources in Book 4 of the Mahābhārata 2020. This book can be freely copied and distributed for no commercial uses. Licence Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) Cover: Jaime Wulff 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book* has greatly benefited from the patience and curiosity of several people. I am especially grateful to the scholars who participated in the seminars held at the Universities of Rome-La Sapienza, in particular Raffaele Torella, at Cardiff University James Hegarty, at the University of Seville Alberto Bernabé Pajares, and Greg Wolff at the Institute of Classical Studies, University of London. I would also like to thank Cardiff University and the Institute of Classical Studies for accepting me as a visiting researcher. Other people who have been essential to the production of this book are Alf Hiltebeitel, Andrew Morrow, Nick Trillwood and my colleagues at the University of Malaga. I would also like to express my gratitude for the anonymous and, so often, thankless labour carried out by countless colleagues who generously make our work possible by curating the collections found on several key online databases such as, GRETIL (Göttingen Register of Electronic Texts in Indian Languages), University of Heidelberg’s DCS (Digital Corpus of Sanskrit) and Perseus Digital Library of Tufts University. And finally, there are two people who have been absolutely pivotal to this book. -

Investigating Sources of Mercury's Crustal

49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2018 (LPI Contrib. No. 2083) 2109.pdf INVESTIGATING SOURCES OF MERCURY’S CRUSTAL MAGNETIC FIELD: FURTHER MAPPING OF MESSENGER MAGNETOMETER DATA. L. L. Hood1, J. S. Oliveira2,3, P. D. Spudis4, V. Galluzzi5, 1Lunar & Planetary Lab, 1629 E. University Blvd., Univ. of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA; [email protected], 2ESA/ESTEC, SCI-S, Keplerlaan 1, 2200 AG Noordwijk, Netherlands; 3CITEUC, Geophysi- cal & Astronomical Observatory, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal ([email protected] ); 4Lunar & Planetary Institute, USRA, Houston, TX; 5INAF, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Rome, Italy. Introduction: A valuable data set for investigating the orbit tracks was accomplished in two substeps. crustal magnetism on Mercury was obtained by the First, a cubic polynomial was least-squares fitted to the NASA MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEo- raw radial component time series for each orbit pass. chemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) Discovery Second, the deviation from 5o running averages was mission during the final year of its existence [1]. Alti- calculated to eliminate wavelengths greater than about tude normalized maps of the crustal field covering part 215 km. At 60oN, the spacecraft altitude decreased of one side of the planet (90oE to 270oE; 35oN to75oN) from 35 km on March 16 to 5.2 km on April 2 when an have previously been constructed from low-altitude orbit correction burn occurred, increasing the altitude magnetometer data using an equivalent source dipole to 28 km. Several other orbit correction burns pre- (ESD) technique [2,3]. Results showed that the stron- vented the altitude at 60oN from decreasing below 8.8 gest crustal field anomalies in this region are concen- km during the period from April 2 to 23. -

The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita

THE SACRED BOOKS OFTHEEAST Volume 8 SACRED BOOKS OF THE EAST EDITOR: F. Max Muller These volumes of the Sacred Books of the East Series include translations of all the most important works of the seven non Christian religions. These have exercised a profound innuence on the civilizations of the continent of Asia. The Vedic Brahmanic System claims 21 volumes, Buddhism 10, and Jainism 2;8 volumes comprise Sacred Books of the Parsees; 2 volumes represent Islam; and 6 the two main indigenous systems of China. thus placing the historical and comparative study of religions on a solid foundation. VOLUMES 1,15. TilE UPANISADS: in 2 Vols. F. Max Muller 2,14. THE SACRED LAWS OF THE AR VAS: in 2 vols. Georg Buhler 3,16,27,28,39,40. THE SACRED BOOKS OF CHINA: In 6 Vols. James Legge 4,23,31. The ZEND-AVESTA: in 3 Vols. James Darmesleler & L.H. Mills 5, 18,24,37,47. PHALVI TEXTS: in 5 Vall. E. W. West 6,9. THE QUR' AN: in 2 Vols. E. H. Palmer 7. The INSTITUTES OF VISNU: J.Jolly R. THE BHAGA VADGITAwith lhe Sanalsujllliya and the Anugilii: K.T. Telang 10. THE DHAMMAPADA: F. Max Muller SUTTA-NIPATA: V. Fausbiill 1 I. BUDDHIST SUTTAS: T.W. Rhys Davids 12,26,41,43,44. VINAYA TEXTS: in 3 Vols. T.W. Rhys Davids & II. Oldenberg 19. THE FO·SHO-HING·TSANG·KING: Samuel Beal 21. THE SADDHARMA-PUM>ARlKA or TilE LOTUS OF THE TRUE LAWS: /I. Kern 22,45. lAINA SUTRAS: in 2 Vols. -

Gods Or Aliens? Vimana and Other Wonders

Gods or Aliens? Vimana and other wonders Parama Karuna Devi Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2017 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved ISBN-13: 978-1720885047 ISBN-10: 1720885044 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Table of contents Introduction 1 History or fiction 11 Religion and mythology 15 Satanism and occultism 25 The perspective on Hinduism 33 The perspective of Hinduism 43 Dasyus and Daityas in Rig Veda 50 God in Hinduism 58 Individual Devas 71 Non-divine superhuman beings 83 Daityas, Danavas, Yakshas 92 Khasas 101 Khazaria 110 Askhenazi 117 Zarathustra 122 Gnosticism 137 Religion and science fiction 151 Sitchin on the Annunaki 161 Different perspectives 173 Speculations and fragments of truth 183 Ufology as a cultural trend 197 Aliens and technology in ancient cultures 213 Technology in Vedic India 223 Weapons in Vedic India 238 Vimanas 248 Vaimanika shastra 259 Conclusion 278 The author and the Research Center 282 Introduction First of all we need to clarify that we have no objections against the idea that some ancient civilizations, and particularly Vedic India, had some form of advanced technology, or contacts with non-human species or species from other worlds. In fact there are numerous genuine texts from the Indian tradition that contain data on this subject: the problem is that such texts are often incorrectly or inaccurately quoted by some authors to support theories that are opposite to the teachings explicitly presented in those same original texts. -

The Bhagavad Gita: Ancient Poem, Modern Readers

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the current Summer Seminars and Institutes guidelines, which reflect the most recent information and instructions, at https://www.neh.gov/program/summer-seminars-and-institutes-higher-education-faculty Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Education Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: The Bhagavad Gita: Ancient Poem, Modern Readers Institution: Bard College Project Director: Richard Davis Grant Program: Summer Seminars and Institutes (Seminar for Higher Education Faculty) 400 7th Street, SW, Washington, DC 20024 P 202.606.8500 F 202.606.8394 [email protected] www.neh.gov The Bhagavad Gita: Ancient Poem, Modern Readers Summer Seminar for College and University Teachers Director: Richard H. Davis, Bard College Table of Contents I. Table of Contents ………………………………………………………………………. i II. Narrative Description …………………………………………………………………. 1 A. Intellectual rationale …………………………………………………………... 1 B. Program of study ……………………………………………………………… 7 C. Project faculty and staff ……………………………………………………… 12 D. -

Rationale for Bepicolombo Studies of Mercury's Surface and Composition

Space Sci Rev (2020) 216:66 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-020-00694-7 Rationale for BepiColombo Studies of Mercury’s Surface and Composition David A. Rothery1 · Matteo Massironi2 · Giulia Alemanno3 · Océane Barraud4 · Sebastien Besse5 · Nicolas Bott4 · Rosario Brunetto6 · Emma Bunce7 · Paul Byrne8 · Fabrizio Capaccioni9 · Maria Teresa Capria9 · Cristian Carli9 · Bernard Charlier10 · Thomas Cornet5 · Gabriele Cremonese11 · Mario D’Amore3 · M. Cristina De Sanctis9 · Alain Doressoundiram4 · Luigi Ferranti12 · Gianrico Filacchione9 · Valentina Galluzzi9 · Lorenza Giacomini9 · Manuel Grande13 · Laura G. Guzzetta9 · Jörn Helbert3 · Daniel Heyner14 · Harald Hiesinger15 · Hauke Hussmann3 · Ryuku Hyodo16 · Tomas Kohout17 · Alexander Kozyrev18 · Maxim Litvak18 · Alice Lucchetti11 · Alexey Malakhov18 · Christopher Malliband1 · Paolo Mancinelli19 · Julia Martikainen20,21 · Adrian Martindale7 · Alessandro Maturilli3 · Anna Milillo22 · Igor Mitrofanov18 · Maxim Mokrousov18 · Andreas Morlok15 · Karri Muinonen20,23 · Olivier Namur24 · Alan Owens25 · Larry R. Nittler26 · Joana S. Oliveira27,28 · Pasquale Palumbo29 · Maurizio Pajola11 · David L. Pegg1 · Antti Penttilä20 · Romolo Politi9 · Francesco Quarati30 · Cristina Re11 · Anton Sanin18 · Rita Schulz25 · Claudia Stangarone3 · Aleksandra Stojic15 · Vladislav Tretiyakov18 · Timo Väisänen20 · Indhu Varatharajan3 · Iris Weber15 · Jack Wright1 · Peter Wurz31 · Francesca Zambon22 Received: 20 December 2019 / Accepted: 13 May 2020 / Published online: 2 June 2020 © The Author(s) 2020 The BepiColombo mission -

Bhaga Vad-Gita

THE HISTORICAL GAME-CHANGES IN THE PHILOSOPHY OF DEVOTION AND CASTE AS USED AND MISUSED BY THE BHAGA VAD-GITA BY - ,<" DR. THILAGAVATHI CHANDULAL BA, MBBS (Madras), MRCOG, FRCOG (UK), MDiv. (Can) TOWARDS THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MA IN PHILOSOPHY TO THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES BROCK UNIVERSITY ST. CATHARINES, ONTARIO, CANADA, L2S 2Al © 5 JANUARY 2011 11 THREE EPIGRAPHS ON THE ATHLETE OF THE SPffiIT Majority of us are born, eddy around, die only to glut the grave. Some - begin the quest, 'eddy around, but at the first difficulty, getting frightened, regress to the non-quest inertia. A few set out, but a very small number make it to the mountain top. Mathew Arnold, Rugby Chapel Among thousands of men scarcely one strives for perfection, and even among these who strive and succeed, scarcely one knows Me in truth. The Bhagavad-Gita 7. 3 Do you not know that in a race the runners all compete, but only one receives the prize? Run in such a way that you may win it. Athletes exercise self-control in all things; they do it to receive a perishable wreath, but we an imperishable one. St. Paul, First Letter to the Corinthian Church, 9.24-25 111 Acknowledging my goodly, heritage Father, Savarimuthu's world-class expertise in Theology: Christian, Lutheran and Hindu Mother, Annapooranam, who exemplified Christian bhakti and nlJrtured me in it ~ Aunt, Kamalam, who founded Tamil grammar and literature in me in my pre-teen years Daughter, Rachel, who has always been supportive of my education Grandchildren, Charisa and Chara, who love and admire me All my teachers all my years iv CONTENTS Abstract v Preface VI Tables, Lists, Abbreviations IX Introduction to bhakti X Chronological Table XVI Etymology of bhakti (Sanskrit), Grace (English), Anbu (Tamil), Agape (Greek) XVll Origin and Growth of bhakti xx Agape (love) XXI Chapter 1: Game-Changes in bhakti History: 1 Vedic devotion Upanishadic devotion Upanishads and bhakti The Epics and bhakti The Origin of bhakti . -

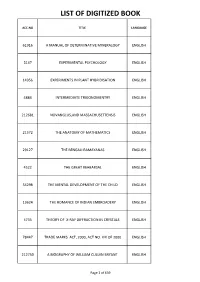

List of Digitized Book

LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK ACC.NO TITLE LANGUAGE 61916 A MANUAL OF DETERMINATIVE MINERALOGY ENGLISH 5147 EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY ENGLISH 14956 EXPERIMENTS IN PLANT HYBRIDISATION ENGLISH 4884 INTERMEDIATE TRIGONOMENTRY ENGLISH 212681 NOVANGLUS,AND MASSACHUSETTENSIS ENGLISH 21572 THE ANATOMY OF MATHEMATICS ENGLISH 29127 THE BENGALI RAMAYANAS ENGLISH 4522 THE GREAT REHEARSAL ENGLISH 54298 THE MENTAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE CHILD ENGLISH 13624 THE ROMANCE OF INDIAN EMBROADERY ENGLISH 4735 THEORY OF X-RAY DIFFRACTION IN CRYSTALS ENGLISH 78447 TRADE MARKS ACT, 2000, ACT NO. XIX OF 2000 ENGLISH 212750 A BIOGRAPHY OF WILLIAM CULLEN BRYANT ENGLISH Page 1 of 639 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 1189 A BOOK OF BOTH SPORTS ENGLISH CA_3228 A BOOK OF WORDS ENGLISH 5376 A BRIEF BIOLOGY ENGLISH ASL_234 A BRIEF HISTORY OF SHAH-HAMDAN-MOSQUE ENGLISH 9877 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES ENGLISH 153159 A CATALOGUE OF INDIAN SYNONMES ENGLISH 10631 A CHANGED MAN AND OTHER TALES ENGLISH 14410 A CHAUCER SELECTION ENGLISH 120567 A CHOICE OF KIPLING'S VERSE ENGLISH 59529 A CHRISTMAS CAROL ENGLISH 20825 A CHRISTMAS GARLAND ENGLISH 973 A COAT OF MANY COLOURS ENGLISH 491019 A COLLECTION OF PAPERS ENGLISH 14573 A COMMERCIAL COURSE FOR FOREIGN STUDENTS ENGLISH Page 2 of 639 LIST OF DIGITIZED BOOK 73364 A CONCISE ECONOMIC HISTORY OF BRITAIN ENGLISH A CONTRIBUTION TO THE THEORY OF THE TRADE 134801 ENGLISH CYCLE 20121 A COURSE IN GENERAL CHEMISTRY ENGLISH 162546 A COURSE OF MODERN ANALYSIS ENGLISH 20368 A COURSE OF STUDY IN CHEMICAL PRINCIPLES ENGLISH 70174 A CRITICAL HISTORY OF ENGLISH -

History of Science and Technology in India

DDCE/History (M.A)/SLM/Paper HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY IN INDIA By Dr. Binod Bihari Satpathy 1 CONTENT HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY IN INDIA Unit.No. Chapter Name Page No Unit-I. Science and Technology- The Beginning 1. Development in different branches of Science in Ancient India: 03-28 Astronomy, Mathematics, Engineering and Medicine. 2. Developments in metallurgy: Use of Copper, Bronze and Iron in 29-35 Ancient India. 3. Development of Geography: Geography in Ancient Indian Literature. 36-44 Unit-II Developments in Science and Technology in Medieval India 1. Scientific and Technological Developments in Medieval India; 45-52 Influence of the Islamic world and Europe; The role of maktabs, madrasas and karkhanas set up. 2. Developments in the fields of Mathematics, Chemistry, Astronomy 53-67 and Medicine. 3. Innovations in the field of agriculture - new crops introduced new 68-80 techniques of irrigation etc. Unit-III. Developments in Science and Technology in Colonial India 1. Early European Scientists in Colonial India- Surveyors, Botanists, 81-104 Doctors, under the Company‘s Service. 2. Indian Response to new Scientific Knowledge, Science and 105-116 Technology in Modern India: 3. Development of research organizations like CSIR and DRDO; 117-141 Establishment of Atomic Energy Commission; Launching of the space satellites. Unit-IV. Prominent scientist of India since beginning and their achievement 1. Mathematics and Astronomy: Baudhayan, Aryabhtatta, Brahmgupta, 142-158 Bhaskaracharya, Varahamihira, Nagarjuna. 2. Medical Science of Ancient India (Ayurveda & Yoga): Susruta, 159-173 Charak, Yoga & Patanjali. 3. Scientists of Modern India: Srinivas Ramanujan, C.V. Raman, 174-187 Jagdish Chandra Bose, Homi Jehangir Bhabha and Dr.