Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Understanding of Maya: the Philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva

An understanding of Maya: The philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva Department of Religion studies Theology University of Pretoria By: John Whitehead 12083802 Supervisor: Dr M Sukdaven 2019 Declaration Declaration of Plagiarism 1. I understand what plagiarism means and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this Dissertation is my own work. 3. I did not make use of another student’s previous work and I submit this as my own words. 4. I did not allow anyone to copy this work with the intention of presenting it as their own work. I, John Derrick Whitehead hereby declare that the following Dissertation is my own work and that I duly recognized and listed all sources for this study. Date: 3 December 2019 Student number: u12083802 __________________________ 2 Foreword I started my MTh and was unsure of a topic to cover. I knew that Hinduism was the religion I was interested in. Dr. Sukdaven suggested that I embark on the study of the concept of Maya. Although this concept provided a challenge for me and my faith, I wish to thank Dr. Sukdaven for giving me the opportunity to cover such a deep philosophical concept in Hinduism. This concept Maya is deeper than one expects and has broaden and enlightened my mind. Even though this was a difficult theme to cover it did however, give me a clearer understanding of how the world is seen in Hinduism. 3 List of Abbreviations AD Anno Domini BC Before Christ BCE Before Common Era BS Brahmasutra Upanishad BSB Brahmasutra Upanishad with commentary of Sankara BU Brhadaranyaka Upanishad with commentary of Sankara CE Common Era EW Emperical World GB Gitabhasya of Shankara GK Gaudapada Karikas Rg Rig Veda SBH Sribhasya of Ramanuja Svet. -

Essays in Philosophy and Yoga

13 Essays in Philosophy and Yoga VOLUME 13 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO © Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 1998 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Essays in Philosophy and Yoga Shorter Works 1910 – 1950 Publisher's Note Essays in Philosophy and Yoga consists of short works in prose written by Sri Aurobindo between 1909 and 1950 and published during his lifetime. All but a few of them are concerned with aspects of spiritual philosophy, yoga, and related subjects. Short writings on the Veda, the Upanishads, Indian culture, politi- cal theory, education, and poetics have been placed in other volumes. The title of the volume has been provided by the editors. It is adapted from the title of a proposed collection, ªEssays in Yogaº, found in two of Sri Aurobindo's notebooks. Since 1971 most of the contents of the volume have appeared under the editorial title The Supramental Manifestation and Other Writings. The contents are arranged in ®ve chronological parts. Part One consists of essays published in the Karmayogin in 1909 and 1910, Part Two of a long essay written around 1912 and pub- lished in 1921, Part Three of essays and other pieces published in the monthly review Arya between 1914 and 1921, Part Four of an essay published in the Standard Bearer in 1920, and Part Five of a series of essays published in the Bulletin of Physical Education in 1949 and 1950. Many of the essays in Part Three were revised slightly by the author and published in small books between 1920 and 1941. -

India's Ancient Culture

INDIA’S ANCIENT CULTURE SWAMI KRISHNANANDA The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org Publishers’ Note This book consists of a series of 21 discourses that Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj gave to students in The Divine Life Society's Yoga Vedanta Forest Academy from November 1989 to January 1990. Swamiji Maharaj begins with the earliest stages of Indian culture, and discusses its evolution until the highest level of human achievement, which is liberation of the soul by the realisation of Brahman, the Absolute, through the stages of samadhi. 2 Table of Contents Publishers’ Note………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Chapter 1: The Definition of Culture ............................................................................................ 4 Chapter 2: The Evolution of Culture .......................................................................................... 11 Chapter 3: The Vedas – the Foundation of Indian Culture .............................................. 1 Chapter 4: The Fourfold Aim of and How to Achieve It ............................... 2 8 Chapter 5: Introduction to the Epics ......................................................................................... 3 Life ............ 7 Chapter 6: the Ramayana and the Mahabharata ..................... 4 7 Chapter 7: The Message of the Mahabharata ........................................................................ 5 Similarities between 6 Chapter 8: India’s Concept of Totality ..................................................................................... -

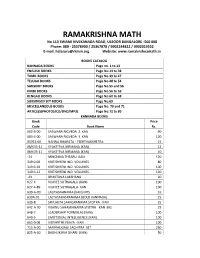

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

Essence of Sanatsujatiya of Maha Bharata

ESSENCE OF SANATSUJATIYA OF MAHA BHARATA Translated, interpreted and edited by V.D.N.Rao 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu, Matsya, Varaha, Kurma, Vamana, Narada, Padma; Shiva, Linga, Skanda, Markandeya, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma, Brahma Vaivarta, Agni, Bhavishya, Nilamata; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa- Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama:a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri;b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata;c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti- Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima- Essence of Ashtaadasha Upanishads: Brihadarankya, Katha, Taittiriya/ Taittiriya Aranyaka , Isha, Svetashvatara, Maha Narayana and Maitreyi, Chhadogya and Kena, Atreya and Kausheetaki, Mundaka, Maandukya, Prashna, Jaabaala and Kaivalya. Also ‗Upanishad Saaraamsa‘ - Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti -Essence of Brahma Sutras- Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Essence of Knowledge of Numbers for students-Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and AusteritiesEssence of Manu Smriti- Quintessence of Manu Smriti- Essence of Paramartha Saara; Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskra; Essence of Pratyaksha Chandra; Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi; Essence -

The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita

THE SACRED BOOKS OFTHEEAST Volume 8 SACRED BOOKS OF THE EAST EDITOR: F. Max Muller These volumes of the Sacred Books of the East Series include translations of all the most important works of the seven non Christian religions. These have exercised a profound innuence on the civilizations of the continent of Asia. The Vedic Brahmanic System claims 21 volumes, Buddhism 10, and Jainism 2;8 volumes comprise Sacred Books of the Parsees; 2 volumes represent Islam; and 6 the two main indigenous systems of China. thus placing the historical and comparative study of religions on a solid foundation. VOLUMES 1,15. TilE UPANISADS: in 2 Vols. F. Max Muller 2,14. THE SACRED LAWS OF THE AR VAS: in 2 vols. Georg Buhler 3,16,27,28,39,40. THE SACRED BOOKS OF CHINA: In 6 Vols. James Legge 4,23,31. The ZEND-AVESTA: in 3 Vols. James Darmesleler & L.H. Mills 5, 18,24,37,47. PHALVI TEXTS: in 5 Vall. E. W. West 6,9. THE QUR' AN: in 2 Vols. E. H. Palmer 7. The INSTITUTES OF VISNU: J.Jolly R. THE BHAGA VADGITAwith lhe Sanalsujllliya and the Anugilii: K.T. Telang 10. THE DHAMMAPADA: F. Max Muller SUTTA-NIPATA: V. Fausbiill 1 I. BUDDHIST SUTTAS: T.W. Rhys Davids 12,26,41,43,44. VINAYA TEXTS: in 3 Vols. T.W. Rhys Davids & II. Oldenberg 19. THE FO·SHO-HING·TSANG·KING: Samuel Beal 21. THE SADDHARMA-PUM>ARlKA or TilE LOTUS OF THE TRUE LAWS: /I. Kern 22,45. lAINA SUTRAS: in 2 Vols. -

Essays in Life and Eternity

EESSSSAAYYSS IINN LLIIFFEE AANNDD EETTEERRNNIITTYY by Swami Krishnananda The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India (Internet Edition: For free distribution only) Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org CONTENTS Preface 4 Introduction 5 Part I – Metaphysical Foundations 11 I - The Absolute And The Relative 11 II - The Universal And The Particular 13 III - The Cosmological Descent 15 IV - The Gods And The Celestial Heaven 17 V - The Human Individual 19 VI - The Evolution Of Consciousness 21 VII - The Epistemological Predicament 23 VIII - The World Of Science 25 IX - Psychology And Psychoanalysis 28 X - Aesthetics And The Field Of Beauty 31 Part II - The Social Scene 33 XI - The Phenomenon Of Society 33 XII - Axiology: The Aims Of Existence 35 XIII - The Nomative Features Of Ethics And Morality 37 XIV - Civic And Social Duty 40 XV - The Economy Of Life 43 XVI - Political Science And Administration 45 XVII - The Process Of History 48 XVIII - Education And Culture 51 Part III - The Development Of Religious Consciousness 54 XIX - The Inklings And Stages Of A Higher Presence 54 XX - The Exploration Of Reality 57 XXI - The Epics And Puranas 60 XXII - The Role Of Mythology In Religion 63 XXIII - The Ecstasy Of God-Love 65 XXIV - The Agama Sastra 67 XXV - Tantra Sadhana 69 XXVI - The Yoga-Vasishtha 72 Essays inin LifeLife andand EternityEternity by by Swami Swami Krishnananda Krishnananda 21 XXVII - Philosophical Proofs For The Existence Of God 75 XXVIII - Empirical Systems Of Philosophy 77 XXIX - The Mimamsa Doctrine Of Works 80 XXX -

The Bhagavad Gita: Ancient Poem, Modern Readers

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the current Summer Seminars and Institutes guidelines, which reflect the most recent information and instructions, at https://www.neh.gov/program/summer-seminars-and-institutes-higher-education-faculty Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Education Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: The Bhagavad Gita: Ancient Poem, Modern Readers Institution: Bard College Project Director: Richard Davis Grant Program: Summer Seminars and Institutes (Seminar for Higher Education Faculty) 400 7th Street, SW, Washington, DC 20024 P 202.606.8500 F 202.606.8394 [email protected] www.neh.gov The Bhagavad Gita: Ancient Poem, Modern Readers Summer Seminar for College and University Teachers Director: Richard H. Davis, Bard College Table of Contents I. Table of Contents ………………………………………………………………………. i II. Narrative Description …………………………………………………………………. 1 A. Intellectual rationale …………………………………………………………... 1 B. Program of study ……………………………………………………………… 7 C. Project faculty and staff ……………………………………………………… 12 D. -

Sri Adi Shankaracharya

Sri Adi Shankaracharya The permanent charm of the name of Sri Shankara Bhagavatpada, the founder of the Sringeri Mutt, lies undoubtedly in the Advaita philosophy he propounded. It is based on the Upanishads and augmented by his incomparable commentaries. He wrote for every one and for all time. The principles, which he formulated, systematized, preached and wrote about, know no limitations of time and place. It cannot be denied that such relics of personal history as still survive of the great Acharya have their own value. It kindles our imagination to visualise him in flesh and blood. It establishes a certain personal rapport instead of a vague conception as an unknown figure of the past. Shankara Vijayas To those who are fortunate to study his valuable works, devotion and gratitude swell up spontaneously in their hearts. His flowing language, his lucid style, his stern logic, his balanced expression, his fearless exposition, his unshakable faith in the Vedas, and other manifold qualities of his works convey an idea of his greatness that no story can adequately convey. To those who are denied the immeasurable happiness of tasting the sweetness of his works, the stories of his earthly life do convey a glimpse of his many-sided personality. Of the chief incidents in his life, there is not much variation among the several accounts entitled 'Shankara Vijayas'. Sri Shankara was born of Shivaguru and Aryamba at Kaladi in Kerala. He lost his father in the third year. He received Gayatri initiation in his fifth year. He made rapid strides in the acquisition of knowledge. -

Bhaga Vad-Gita

THE HISTORICAL GAME-CHANGES IN THE PHILOSOPHY OF DEVOTION AND CASTE AS USED AND MISUSED BY THE BHAGA VAD-GITA BY - ,<" DR. THILAGAVATHI CHANDULAL BA, MBBS (Madras), MRCOG, FRCOG (UK), MDiv. (Can) TOWARDS THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF MA IN PHILOSOPHY TO THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES BROCK UNIVERSITY ST. CATHARINES, ONTARIO, CANADA, L2S 2Al © 5 JANUARY 2011 11 THREE EPIGRAPHS ON THE ATHLETE OF THE SPffiIT Majority of us are born, eddy around, die only to glut the grave. Some - begin the quest, 'eddy around, but at the first difficulty, getting frightened, regress to the non-quest inertia. A few set out, but a very small number make it to the mountain top. Mathew Arnold, Rugby Chapel Among thousands of men scarcely one strives for perfection, and even among these who strive and succeed, scarcely one knows Me in truth. The Bhagavad-Gita 7. 3 Do you not know that in a race the runners all compete, but only one receives the prize? Run in such a way that you may win it. Athletes exercise self-control in all things; they do it to receive a perishable wreath, but we an imperishable one. St. Paul, First Letter to the Corinthian Church, 9.24-25 111 Acknowledging my goodly, heritage Father, Savarimuthu's world-class expertise in Theology: Christian, Lutheran and Hindu Mother, Annapooranam, who exemplified Christian bhakti and nlJrtured me in it ~ Aunt, Kamalam, who founded Tamil grammar and literature in me in my pre-teen years Daughter, Rachel, who has always been supportive of my education Grandchildren, Charisa and Chara, who love and admire me All my teachers all my years iv CONTENTS Abstract v Preface VI Tables, Lists, Abbreviations IX Introduction to bhakti X Chronological Table XVI Etymology of bhakti (Sanskrit), Grace (English), Anbu (Tamil), Agape (Greek) XVll Origin and Growth of bhakti xx Agape (love) XXI Chapter 1: Game-Changes in bhakti History: 1 Vedic devotion Upanishadic devotion Upanishads and bhakti The Epics and bhakti The Origin of bhakti . -

The Key to Theosophy by H. P. Blavatsky

Theosophical University Press Online Edition THE KEY TO THEOSOPHY BY H. P. BLAVATSKY Being a Clear Exposition, in the Form of Question and Answer, of the ETHICS, SCIENCE, AND PHILOSOPHY for the Study of which The Theosophical Society has been Founded. Originally published 1889. Theosophical University Press electronic version ISBN 1- 55700-046-8 (print version also available). Due to current limitations in the ASCII character set, and for ease of searching, no diacritical marks appear in this electronic version of the text. Dedicated by "H. P. B." To all her Pupils that They may Learn and Teach in their turn. CONTENTS PREFACE SECTION 1: THEOSOPHY AND THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY (28K) ● The Meaning of the Name ● The Policy of the Theosophical Society ● The Wisdom-Religion Esoteric in all Ages ● Theosophy is not Buddhism SECTION 2: EXOTERIC AND ESOTERIC THEOSOPHY (44K) ● What the Modern Theosophical Society is not ● Theosophists and Members of the "T. S." ● The Difference between Theosophy and Occultism ● The Difference between Theosophy and Spiritualism ● Why is Theosophy accepted? SECTION 3: THE WORKING SYSTEM OF THE T. S. (22K) ● The Objects of the Society ● The Common Origin of Man ● Our other Objects ● On the Sacredness of the Pledge SECTION 4: THE RELATIONS OF THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY TO THEOSOPHY (15K) ● On Self-Improvement ● The Abstract and the Concrete SECTION 5: THE FUNDAMENTAL TEACHINGS OF THEOSOPHY (39K) ● On God and Prayer ● Is it Necessary to Pray? ● Prayer Kills Self-Reliance ● On the Source of the Human Soul ● The Buddhist -

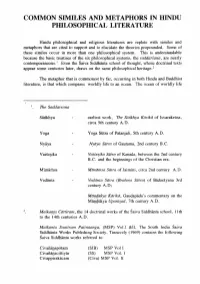

Common Similes and Metaphors in Hindu Pidlosopidcal Literature

COMMON SIMILES AND METAPHORS IN HINDU PIDLOSOPIDCAL LITERATURE Hindu philosophical and religious literatures are replete with similes and metaphors that are cited to support and to elucidate the theories propounded. Some of these similes occur in more than one philosophical system. This is understandable because the basic treatises of the six philosophical systems, the saddarsana, are nearly contemporaneous. I Even the Saiva Siddhanta school of thought, whose doctrinal texts appear some centuries later, draws on the same philosophical heritage. 2 The metaphor that is commonest by far, occurring in both Hindu and Buddhist literature, is that which compares worldly life to an ocean. The ocean of worldly life The Saddarsana Sarikhya earliest work, The Sankhya Karika of Isvarakrsna, circa 5th century A. D. Yoga Yoga Siitra of Patanjali, 5th century A.D. Nyaya Nyaya Surra of Gautama, 2nd century B.C. Vaisesika Yaisesika Surra of Kanada, between the 2nd century B.C. and the beginnings of the Christian era. Mimarnsa Mtmamsa Surra of Jaimini, circa 2nd century A.D. Vedanta Vedanm Surra (Brahm a Siirra) of Badarayana 3rd century A.D; MtitujuJ..ya Karika, Gaudapada's commentary on the Mal}9ukya Upanisad, 7th century A.D. Maikanta Cattiram, the 14 doctrinal works of the Saiva Siddhanta school, 1 Ith to the 14th centuries A.D. Maikanta Saatiram Patinaangu, (MSP) VoU &Il, The South India Saiva Siddhanta Works Publishing Society. Tinnevely (1969) contains the following Saiva Siddhanta works referred to: Civananapotam (S18) MSP Vol I Civafianacitti yar (SS) MSP Vol. I Civappirakacam (Civa) MSP Vol. n COMMON SIMILES AND METAPHORS 29 has to be 'crossed', the root -tr; 'to cross' being often used in this context." And one has to get to the other 'shore', para, which in the context means mokra 'liberation'.