Essays in Life and Eternity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essays in Philosophy and Yoga

13 Essays in Philosophy and Yoga VOLUME 13 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO © Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 1998 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Essays in Philosophy and Yoga Shorter Works 1910 – 1950 Publisher's Note Essays in Philosophy and Yoga consists of short works in prose written by Sri Aurobindo between 1909 and 1950 and published during his lifetime. All but a few of them are concerned with aspects of spiritual philosophy, yoga, and related subjects. Short writings on the Veda, the Upanishads, Indian culture, politi- cal theory, education, and poetics have been placed in other volumes. The title of the volume has been provided by the editors. It is adapted from the title of a proposed collection, ªEssays in Yogaº, found in two of Sri Aurobindo's notebooks. Since 1971 most of the contents of the volume have appeared under the editorial title The Supramental Manifestation and Other Writings. The contents are arranged in ®ve chronological parts. Part One consists of essays published in the Karmayogin in 1909 and 1910, Part Two of a long essay written around 1912 and pub- lished in 1921, Part Three of essays and other pieces published in the monthly review Arya between 1914 and 1921, Part Four of an essay published in the Standard Bearer in 1920, and Part Five of a series of essays published in the Bulletin of Physical Education in 1949 and 1950. Many of the essays in Part Three were revised slightly by the author and published in small books between 1920 and 1941. -

Kartikeya - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

קרטיקייה का셍तिकेय http://www.wisdomlib.org/definition/k%C4%81rtikeya/index.html का셍तिकेय كارتِيكيا کارتيکيا تک ہ का셍तिकेय کا ر یی http://uh.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx Kartikeya - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kartikeya Kartikeya From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Kartikeya (/ˌkɑrtɪˈkeɪjə/), also known as Skanda , Kumaran ,Subramanya , Murugan and Subramaniyan is Kartikeya the Hindu god of war. He is the commander-in-chief of the Murugan army of the devas (gods) and the son of Shiva and Parvati. Subramaniyan God of war and victory, Murugan is often referred to as "Tamil Kadavul" (meaning "God of Tamils") and is worshiped primarily in areas with Commander of the Gods Tamil influences, especially South India, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Reunion Island. His six most important shrines in India are the Arupadaiveedu temples, located in Tamil Nadu. In Sri Lanka, Hindus as well as Buddhists revere the sacred historical Nallur Kandaswamy temple in Jaffna and Katirk āmam Temple situated deep south. [1] Hindus in Malaysia also pray to Lord Murugan at the Batu Caves and various temples where Thaipusam is celebrated with grandeur. In Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, Kartikeya is known as Subrahmanya with a temple at Kukke Subramanya known for Sarpa shanti rites dedicated to Him and another famous temple at Ghati Subramanya also in Karnataka. In Bengal and Odisha, he is popularly known as Kartikeya (meaning 'son of Krittika'). [2] Kartikeya with his wives by Raja Ravi Varma Tamil காத -

India's Ancient Culture

INDIA’S ANCIENT CULTURE SWAMI KRISHNANANDA The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org Publishers’ Note This book consists of a series of 21 discourses that Sri Swami Krishnanandaji Maharaj gave to students in The Divine Life Society's Yoga Vedanta Forest Academy from November 1989 to January 1990. Swamiji Maharaj begins with the earliest stages of Indian culture, and discusses its evolution until the highest level of human achievement, which is liberation of the soul by the realisation of Brahman, the Absolute, through the stages of samadhi. 2 Table of Contents Publishers’ Note………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Chapter 1: The Definition of Culture ............................................................................................ 4 Chapter 2: The Evolution of Culture .......................................................................................... 11 Chapter 3: The Vedas – the Foundation of Indian Culture .............................................. 1 Chapter 4: The Fourfold Aim of and How to Achieve It ............................... 2 8 Chapter 5: Introduction to the Epics ......................................................................................... 3 Life ............ 7 Chapter 6: the Ramayana and the Mahabharata ..................... 4 7 Chapter 7: The Message of the Mahabharata ........................................................................ 5 Similarities between 6 Chapter 8: India’s Concept of Totality ..................................................................................... -

Jagadguru Speaks: Shankara, the World Teacher

Jagadguru Speaks Page 1 of 2 Jagadguru Speaks: Shankara, the World Teacher There are many kinds of people in the world. Their life style is formed in accordance with their own samskaras . Only the one who can show all of them the way to lead a righteous life can be called a Jagadguru . There is no doubt that Adi Sankara was such a Jagadguru . Sankara gave upadesa in jnana to those who wished to tread the path of knowledge. In his works, he has given extensive advice on jnana . For those people who could not go along the jnana marga , he taught karma yoga . His valuable advice to chant the Vedas daily and do the prescribed karmas was meant for those following the path of duty. For those who were unable to follow this advice, he prescribed the way of bhakti . As he said, such people will find it useful to recite the Gita and Vishnusahasranama and think of Hari at all times. The paths of karma , bhakti and jnana are thus conducive to man’s welfare. Adi Sankara who prescribed these various yogas for all people is indeed worshipful. The very remembrance of him is bound to bestow good to all. file://C:\journal\vol1no3\jagadguru.html 9/7/2007 Jagadguru Speaks Page 2 of 2 With absolutely no doubt in my mind, I bow to Sankara Bhagavatpada who, like Lord Siva, was always surrounded by four disciples. file://C:\journal\vol1no3\jagadguru.html 9/7/2007 From the President, SVBF Page 1 of 2 From the President, SVBF Greetings. -

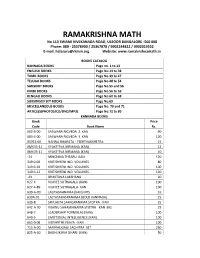

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

Theosophist V9 N103 April 1888

2/—The geological cataclysms of earth ; the frequent absence of inter mediate types in its fauna; the occurrence of architectural and other relics of races now lost, and as to which ordinary science has nothing but vain conjecture; the nature of extinct civilizations and the causes of their extinction; the persistence of savagery and the unequal development of existing civilization; the differences, physical and internal,Jbetween the various races of men; the line of 1 future development. 3.—The contrasts and unisons of the world’s faiths, and the common foundation underlying them all. 4.— The existence of evil, of Buffering, and of sorrow,—a hopeless puzzle THE THEOSOPHIST. to the mere philanthropist or theologian. 5.-—The inequalities in social condition and privilege ; the sharp contrasts between wealth and poverty, intelligence and stupidity, culture and ignorance, virtue and vileness ; the appearance of men of genius in Vol.. IX . N o . 103.—A p r il 1888. families destitute of it, as well as other facts in conflict with the law of heredity ; the frequent cases of unfitness of environment around individuals, so sore as to embitter disposition, hamper aspiration, 1 and paralyse endeavor; the violent antithesis between character and 1 condition; the occurrence of accident, misfortune, and untimely death;— all of them problems solvable only by either the conven tional theory of Divine caprice or the Theosophic doctrines of Karma THERE IS NO RELIGION HIGHER THAN TRUTH. and Re-incarnation. 6.—The possession by individuals of psychic powers, clairvoyance, clair- [Family motto of the Maharajahs of Benares.] audience, &c., as well as the phenomena of psychometry and statuvo- lism. -

Sanatana Dharma)

Aarsha Vani (Voice of Sanatana Dharma) June 2019 Volume: 5 Issue: 05 GURUVĀṆI “The pseudo intellectuals with their extremist adaptations, labeled the culture and way of living in Bhārata dēśa, as Hindu Religion. Anything that is ‘Bhāratīya’ – all forms of knowledge, civilization, traditions, and customs etc., are termed as narrow minded, orthodox and uncivilized. But, the holistic and altruistic study of all the ancient and modern history across the world distinctly promulgate the great truth, ‘the one and only religion that has religious tolerance is the Hindu Religion’.” – Samavedam Shanmukha Sarma. INSIDE THIS ISSUE Dear Readers, Namaste. Scriptures declare that Lord Title Page# Brahma should be worshipped in this month 1 Kalau Gaṅgaiva Kēvalam 1 of Jyestha. ‘How to reach the abode of 2 Siva Padam – ippaṭṭidā sāmī! nī nā sambandhamu 2 Brahma’ explains the spiritual sadhana ṣṭ 3 Jyē ha: 2 required to attain Satyaloka. 4 Worship Brahma in the month of Jyēṣṭhā 2 Brahmasri Dr. Samavedam Shanmukha 5 Agni Tīrtham – Badarī Kṣētram 3 Sarma garu’s article on ‘Not to get into self- 6 ‘Future’ of Bhārata lies in it’s ‘Past’ 4 deception’, describing about religious 7 Garuḍa Mahā Purāṇa 5 conversions and the treacherous mindset of 8 Major Festivals in This Month 6 others, is thought-provoking and awakening 9 The Eternal - Vivāha Vyavastha 8 for moderates. Sadguru Sri Sivananda 10 Vandēhaṁ Śītalāṁ Dēvīṁ... 9 Murthy garu’s article to journey into the past and embrace it more, for a bright future is 11 Who can reach Satya lōka i.e. the abode of Brahma? 10 an eye-opener about the glorious culture of 12 Śiva jñānaṁ - Nīlakaṇṭhamaham Bhaje 11 Bhārata and the eternity of Sanatana 13 Hindu Dharma – Form, Nature of the Divine 12 Dharma. -

Essence of Sanatsujatiya of Maha Bharata

ESSENCE OF SANATSUJATIYA OF MAHA BHARATA Translated, interpreted and edited by V.D.N.Rao 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu, Matsya, Varaha, Kurma, Vamana, Narada, Padma; Shiva, Linga, Skanda, Markandeya, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma, Brahma Vaivarta, Agni, Bhavishya, Nilamata; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa- Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama:a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri;b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata;c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti- Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima- Essence of Ashtaadasha Upanishads: Brihadarankya, Katha, Taittiriya/ Taittiriya Aranyaka , Isha, Svetashvatara, Maha Narayana and Maitreyi, Chhadogya and Kena, Atreya and Kausheetaki, Mundaka, Maandukya, Prashna, Jaabaala and Kaivalya. Also ‗Upanishad Saaraamsa‘ - Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti -Essence of Brahma Sutras- Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Essence of Knowledge of Numbers for students-Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and AusteritiesEssence of Manu Smriti- Quintessence of Manu Smriti- Essence of Paramartha Saara; Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskra; Essence of Pratyaksha Chandra; Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi; Essence -

Jagadguru Sri Jayendra Saraswathi Swamiji an Offering

JAGADGURU SRI JAYENDRA SARASWATHI SWAMIJI AN OFFERING ॎश्रीगु셁भ्योनमः P.R.KANNAN,M.Tech. Navi Mumbai Released during the SAHASRADINA SATHABHISHEKAMCELEBRATIONS of Jagadguru Sri JAYENDRA SARASWATHI SWAMIJI Sankaracharya of Moolamnaya Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham Kanchipuram August 2016 Page 2 of 152 भक्तिर्ज्ञानंक्तिनीक्ततःशमदमसक्तितंमञनसंतुक्तियुिं प्रर्ज्ञक्तिेक्ततसिंशुभगुणक्तिभिञऐक्तिकञमुक्तममकञश्च। प्रञप्ञःश्रीकञमकोटीमठ-क्तिमलगुरोयास्यपञदञर्ानञन्मे तस्यश्रीपञदपेभितुकृक्ततररयंपुमपमञलञसमञनञ॥ May this garland of flowers adorn the lotus feet of the ever-pure Guru of Sri Kamakoti Matham, whose worship has bestowed on me devotion, supreme experience, humility, control of sense organs and thought, contented mind, awareness, knowledge and all glorious and auspicious qualities for life here and hereafter. Acknowledgements: This compilation derives information from many sources including, chiefly „Kanchi Kosh‟ published on 31st March 2004 by Kanchi Kamakoti Jagadguru Sri Jayendra Saraswati Swamiji Peetarohana Swarna Jayanti Mahotsav Trust, „Sri Jayendra Vijayam‟ (in Tamil) – parts 1 and 2 by Sri M.Jaya Senthilnathan, published by Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham, and „Jayendra Vani‟ – Vol. I and II published in 2003 by Kanchi Kamakoti Jagadguru Sri Jayendra Saraswati Swamiji Peetarohana Swarna Jayanti Mahotsav Trust. The author expresses his gratitude for all the assistance obtained in putting together this compilation. Author: P.R. Kannan, M.Tech., Navi Mumbai. Mob: 9860750020; email: [email protected] Page 3 of 152 P.R.Kannan of Navi Mumbai, our Srimatham‟s very dear disciple, has been rendering valuable service by translating many books from Itihasas, Puranas and Smritis into Tamil and English as instructed by Sri Acharya Swamiji and publishing them in Internet and many spiritual magazines. -

Talks with Ramana

Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi Volume II 23rd August, 1936 Talk 240. D.: The world is materialistic. What is the remedy for it? M.: Materialistic or spiritual, it is according to your outlook. Drishtim jnanamayim kritva, Brahma mayam pasyet jagat Make your outlook right. The Creator knows how to take care of His Creation. D.: What is the best thing to do for ensuring the future? M.: Take care of the present, the future will take care of itself. D.: The future is the result of the present. So, what should I do to make it good? Or should I keep still? M.: Whose is the doubt? Who is it that wants a course of action? Find the doubter. If you hold the doubter the doubts will disappear. Having lost hold of the Self the thoughts afflict you; the world is seen, doubts arise, also anxiety for the future. Hold fast to the Self, these will disappear. D.: How to do it? M.: This question is relevant to matters of non-self, but not to the Self. Do you doubt the existence of your own Self? D.: No. But still, I want to know how the Self could be realised. Is there any method leading to it? M.: Make effort. Just as water is got by boring a well, so also you realise the Self by investigation. D.: Yes. But some find water readily and others with difficulty. M.: But you already see the moisture on the surface. You are hazily aware of the Self. Pursue it. When the effort ceases the Self shines forth. -

Did Sri Shankara Establish the Six Sects?

1 Did Sri Shankara establish the six sects? (Translated to English from the original Kannada article https://adbhutam.files.wordpress.com/2021/06/shankara-shanmata-kan.pdf By Sri K.Sathyanarayana) There is a general belief that Sri Shankara BhagavatpAda established the six sects namely Shaiva, VaishNava, ShAkta, Soura, GANapatya and SkAnda. The dieties respectively worshipped in these sects are Shiva, VishNu, Devi, Surya, GaNapati and Skanda. The purport is that the followers of those sects may meditate on the respective diety as ParaBrahma and attain liberation. Sri Shankaracharya AshTOttara (108 names used to worship Shankara) contains the name to the effect that the Acharya established the six schools. But there is no direct mention of the fact in any well-known text. As such, there is also a school that says there is no relation at all between Sri Shankara BhagavatpAda and these six sects. In this article, we explore the relation between Sri Shankara BhagavatpAda and these six sects, mainly on the basis of PrasthAna traya BhAshya. Shaiva Sri Shankara has cited the ShvetAshvatara Upanishat in many contexts. One example: ‘ स कारण ं करणाधिपाधिपो न चास्य कधिज्जधनता न चाधिपः’ (श्व.े उ. ६ । ९) इधत च ब्रह्मणो जनधितारं वारिधत । Brahma sUtra BhAshya 2.3.9. This sentence states: ‘There is no prior cause for Brahman, whatsoever.’ In this Upanishat, Rudra is stated to be the Para Brahman, the cause for the universe. Here is an elaboration of this Upanishat on the aspect of Rudra being the Brahman: https://adbhutam.wordpress.com/2021/03/09/the-advaitins-shanti-mantra- shvetashvatara-up-and-a-glimple-of-the-shiva-purana/ 2 VaishNava: On several occasions in various BhAshyas, Sri Shankara has mentioned VishNu / nArAyaNa as Para Brahman: ‘ अति सक्षं पे धिि ं �णध्वु ं नारािणः सवधव िद ं परु ाणः । स स셍कव ाले च करोधत सवं सहं ारकाले च तदधि भिू ः’ इधत परु ाण े ; भ셍वद्गीतास ु च — ‘ अहं कृ त्स्नस्य ज셍तः प्रभवः प्रलिस्तथा’ (भ. -

The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita

THE SACRED BOOKS OFTHEEAST Volume 8 SACRED BOOKS OF THE EAST EDITOR: F. Max Muller These volumes of the Sacred Books of the East Series include translations of all the most important works of the seven non Christian religions. These have exercised a profound innuence on the civilizations of the continent of Asia. The Vedic Brahmanic System claims 21 volumes, Buddhism 10, and Jainism 2;8 volumes comprise Sacred Books of the Parsees; 2 volumes represent Islam; and 6 the two main indigenous systems of China. thus placing the historical and comparative study of religions on a solid foundation. VOLUMES 1,15. TilE UPANISADS: in 2 Vols. F. Max Muller 2,14. THE SACRED LAWS OF THE AR VAS: in 2 vols. Georg Buhler 3,16,27,28,39,40. THE SACRED BOOKS OF CHINA: In 6 Vols. James Legge 4,23,31. The ZEND-AVESTA: in 3 Vols. James Darmesleler & L.H. Mills 5, 18,24,37,47. PHALVI TEXTS: in 5 Vall. E. W. West 6,9. THE QUR' AN: in 2 Vols. E. H. Palmer 7. The INSTITUTES OF VISNU: J.Jolly R. THE BHAGA VADGITAwith lhe Sanalsujllliya and the Anugilii: K.T. Telang 10. THE DHAMMAPADA: F. Max Muller SUTTA-NIPATA: V. Fausbiill 1 I. BUDDHIST SUTTAS: T.W. Rhys Davids 12,26,41,43,44. VINAYA TEXTS: in 3 Vols. T.W. Rhys Davids & II. Oldenberg 19. THE FO·SHO-HING·TSANG·KING: Samuel Beal 21. THE SADDHARMA-PUM>ARlKA or TilE LOTUS OF THE TRUE LAWS: /I. Kern 22,45. lAINA SUTRAS: in 2 Vols.