India's Ancient Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Essays in Philosophy and Yoga

13 Essays in Philosophy and Yoga VOLUME 13 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO © Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 1998 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Essays in Philosophy and Yoga Shorter Works 1910 – 1950 Publisher's Note Essays in Philosophy and Yoga consists of short works in prose written by Sri Aurobindo between 1909 and 1950 and published during his lifetime. All but a few of them are concerned with aspects of spiritual philosophy, yoga, and related subjects. Short writings on the Veda, the Upanishads, Indian culture, politi- cal theory, education, and poetics have been placed in other volumes. The title of the volume has been provided by the editors. It is adapted from the title of a proposed collection, ªEssays in Yogaº, found in two of Sri Aurobindo's notebooks. Since 1971 most of the contents of the volume have appeared under the editorial title The Supramental Manifestation and Other Writings. The contents are arranged in ®ve chronological parts. Part One consists of essays published in the Karmayogin in 1909 and 1910, Part Two of a long essay written around 1912 and pub- lished in 1921, Part Three of essays and other pieces published in the monthly review Arya between 1914 and 1921, Part Four of an essay published in the Standard Bearer in 1920, and Part Five of a series of essays published in the Bulletin of Physical Education in 1949 and 1950. Many of the essays in Part Three were revised slightly by the author and published in small books between 1920 and 1941. -

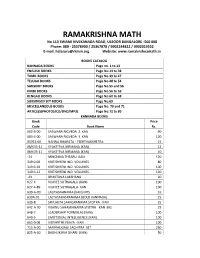

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 4

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) BLANK DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 4 Compiled by VASANT MOON Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 4 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : October 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. In pursuance of the recommendations of the Centenary Celebrations Committee of Dr. -

Essence of Sanatsujatiya of Maha Bharata

ESSENCE OF SANATSUJATIYA OF MAHA BHARATA Translated, interpreted and edited by V.D.N.Rao 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu, Matsya, Varaha, Kurma, Vamana, Narada, Padma; Shiva, Linga, Skanda, Markandeya, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma, Brahma Vaivarta, Agni, Bhavishya, Nilamata; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa- Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama:a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri;b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata;c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti- Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima- Essence of Ashtaadasha Upanishads: Brihadarankya, Katha, Taittiriya/ Taittiriya Aranyaka , Isha, Svetashvatara, Maha Narayana and Maitreyi, Chhadogya and Kena, Atreya and Kausheetaki, Mundaka, Maandukya, Prashna, Jaabaala and Kaivalya. Also ‗Upanishad Saaraamsa‘ - Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti -Essence of Brahma Sutras- Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Essence of Knowledge of Numbers for students-Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and AusteritiesEssence of Manu Smriti- Quintessence of Manu Smriti- Essence of Paramartha Saara; Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskra; Essence of Pratyaksha Chandra; Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi; Essence -

Vedic Period Language and Literature

Study of Vedic Period Language and Literature Prem Nagar Overview Introduction to the Vedas Vedic Language Characteristics of the Vedic Language Vedic Literature Contents of the Vedic Literature Retention of the Vedic Literature Vedic Period: Language and Literature 2 Introduction to the Veda (वेद) Vedas are believed to be the earliest literary composition of the world! Text and Contents: • They are scriptural poetic narratives of undetermined age containing prayers, philosophical dialogue, myth, ritual chants and invocation. • They helped develop ritualistic procedures, social organization and an ethical code of conduct. • The language and grammar appear local in origin. Transmission: • Composition in chhandas (छ�:, meters) helped transmission over time. Lasting Impact • Prayers and rituals are used for atonement and to alleviate grief. • Philosophy and prescribed belief systems provided a foundation for culture in India. Vedic Period: Language and Literature 3 What is Veda (वेद) • Word Veda (वेद) signifies knowledge, traditionally considered eternal. • The Vedas were handed down orally and are called śruti (श्रुित) literature: Rig-Veda (ऋ�ेद ) (RV) - Hymns of Praise (recitation) Sama-Veda (सामवेद) (SV) - Knowledge of the Melodies Yajur-Veda (यजुव�द) (YV) - Sacrificial rituals for liturgy Atharva-Veda (अथव�वेद) (AV) - Formulas • They fall into four classes of literary works: Samhitås (संिहता): rule-based verses (collection of hymns) Aranyakas (आर�क): developed beliefs (theological explanation) Brāhmaṇa (ब्रा�णम्): explanations of rituals (ceremonies, sacrifices) Upanishads (उपिनषद् ): philosophy that has Vedic essence • The Rig-Veda Samhitås are organized into: 1. Mandalas (म�ल, books) consisting of hymns called sūkta 2. Sūktas (सू�) consist of individual ṛcs (stanzas) 3. -

The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita

THE SACRED BOOKS OFTHEEAST Volume 8 SACRED BOOKS OF THE EAST EDITOR: F. Max Muller These volumes of the Sacred Books of the East Series include translations of all the most important works of the seven non Christian religions. These have exercised a profound innuence on the civilizations of the continent of Asia. The Vedic Brahmanic System claims 21 volumes, Buddhism 10, and Jainism 2;8 volumes comprise Sacred Books of the Parsees; 2 volumes represent Islam; and 6 the two main indigenous systems of China. thus placing the historical and comparative study of religions on a solid foundation. VOLUMES 1,15. TilE UPANISADS: in 2 Vols. F. Max Muller 2,14. THE SACRED LAWS OF THE AR VAS: in 2 vols. Georg Buhler 3,16,27,28,39,40. THE SACRED BOOKS OF CHINA: In 6 Vols. James Legge 4,23,31. The ZEND-AVESTA: in 3 Vols. James Darmesleler & L.H. Mills 5, 18,24,37,47. PHALVI TEXTS: in 5 Vall. E. W. West 6,9. THE QUR' AN: in 2 Vols. E. H. Palmer 7. The INSTITUTES OF VISNU: J.Jolly R. THE BHAGA VADGITAwith lhe Sanalsujllliya and the Anugilii: K.T. Telang 10. THE DHAMMAPADA: F. Max Muller SUTTA-NIPATA: V. Fausbiill 1 I. BUDDHIST SUTTAS: T.W. Rhys Davids 12,26,41,43,44. VINAYA TEXTS: in 3 Vols. T.W. Rhys Davids & II. Oldenberg 19. THE FO·SHO-HING·TSANG·KING: Samuel Beal 21. THE SADDHARMA-PUM>ARlKA or TilE LOTUS OF THE TRUE LAWS: /I. Kern 22,45. lAINA SUTRAS: in 2 Vols. -

Essays in Life and Eternity

EESSSSAAYYSS IINN LLIIFFEE AANNDD EETTEERRNNIITTYY by Swami Krishnananda The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India (Internet Edition: For free distribution only) Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org CONTENTS Preface 4 Introduction 5 Part I – Metaphysical Foundations 11 I - The Absolute And The Relative 11 II - The Universal And The Particular 13 III - The Cosmological Descent 15 IV - The Gods And The Celestial Heaven 17 V - The Human Individual 19 VI - The Evolution Of Consciousness 21 VII - The Epistemological Predicament 23 VIII - The World Of Science 25 IX - Psychology And Psychoanalysis 28 X - Aesthetics And The Field Of Beauty 31 Part II - The Social Scene 33 XI - The Phenomenon Of Society 33 XII - Axiology: The Aims Of Existence 35 XIII - The Nomative Features Of Ethics And Morality 37 XIV - Civic And Social Duty 40 XV - The Economy Of Life 43 XVI - Political Science And Administration 45 XVII - The Process Of History 48 XVIII - Education And Culture 51 Part III - The Development Of Religious Consciousness 54 XIX - The Inklings And Stages Of A Higher Presence 54 XX - The Exploration Of Reality 57 XXI - The Epics And Puranas 60 XXII - The Role Of Mythology In Religion 63 XXIII - The Ecstasy Of God-Love 65 XXIV - The Agama Sastra 67 XXV - Tantra Sadhana 69 XXVI - The Yoga-Vasishtha 72 Essays inin LifeLife andand EternityEternity by by Swami Swami Krishnananda Krishnananda 21 XXVII - Philosophical Proofs For The Existence Of God 75 XXVIII - Empirical Systems Of Philosophy 77 XXIX - The Mimamsa Doctrine Of Works 80 XXX -

Gods Or Aliens? Vimana and Other Wonders

Gods or Aliens? Vimana and other wonders Parama Karuna Devi Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2017 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved ISBN-13: 978-1720885047 ISBN-10: 1720885044 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Table of contents Introduction 1 History or fiction 11 Religion and mythology 15 Satanism and occultism 25 The perspective on Hinduism 33 The perspective of Hinduism 43 Dasyus and Daityas in Rig Veda 50 God in Hinduism 58 Individual Devas 71 Non-divine superhuman beings 83 Daityas, Danavas, Yakshas 92 Khasas 101 Khazaria 110 Askhenazi 117 Zarathustra 122 Gnosticism 137 Religion and science fiction 151 Sitchin on the Annunaki 161 Different perspectives 173 Speculations and fragments of truth 183 Ufology as a cultural trend 197 Aliens and technology in ancient cultures 213 Technology in Vedic India 223 Weapons in Vedic India 238 Vimanas 248 Vaimanika shastra 259 Conclusion 278 The author and the Research Center 282 Introduction First of all we need to clarify that we have no objections against the idea that some ancient civilizations, and particularly Vedic India, had some form of advanced technology, or contacts with non-human species or species from other worlds. In fact there are numerous genuine texts from the Indian tradition that contain data on this subject: the problem is that such texts are often incorrectly or inaccurately quoted by some authors to support theories that are opposite to the teachings explicitly presented in those same original texts. -

Riddles in Hinduism

Bharat Ratna Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar "Father Of Indian Constitution" India’s first Law Minister Architect of the Constitution of India ii http://www.ambedkar.org Born April 14, 1891, Mhow, India Died Dec. 6, 1956, New Delhi Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, was the first Minister of Law soon after the Independence of India in 1947 and was the Chairman of the drafting committee for the Constitution of India As such he was chiefly responsible for drafting of The Constitution of India. Ambedkar was born on the 14 th April, 1891. After graduating from Elphinstone College, Bombay in 1912, he joined Columbia University, USA where he was awarded Ph.D. Later he joined the London School of Economics & obtained a degree of D.Sc. ( Economics) and was called to the Bar from Gray's Inn. He returned to India in 1923 and started the 'Bahishkrit Hitkarini Sabha' for the education and economic improvement of the lower classes from where he came. One of the greatest contributions of Dr. Ambedkar was in respect of Fundamental Rights & Directive Principles of State Policy enshrined in the Constitution of India. The Fundamental Rights provide for freedom, equality, and abolition of Untouchability & remedies to ensure the enforcement of rights. The Directive Principles enshrine the broad guiding principles for securing fair distribution of wealth & better living conditions. On the 14 th October, 1956, Babasaheb Ambedkar a scholar in Hinduism embraced Buddhism. He continued the crusade for social revolution until the end of his life on the 6th December 1956. He was honoured with the highest national honour, 'Bharat Ratna' in April 1990 . -

Sri Adi Shankaracharya

Sri Adi Shankaracharya The permanent charm of the name of Sri Shankara Bhagavatpada, the founder of the Sringeri Mutt, lies undoubtedly in the Advaita philosophy he propounded. It is based on the Upanishads and augmented by his incomparable commentaries. He wrote for every one and for all time. The principles, which he formulated, systematized, preached and wrote about, know no limitations of time and place. It cannot be denied that such relics of personal history as still survive of the great Acharya have their own value. It kindles our imagination to visualise him in flesh and blood. It establishes a certain personal rapport instead of a vague conception as an unknown figure of the past. Shankara Vijayas To those who are fortunate to study his valuable works, devotion and gratitude swell up spontaneously in their hearts. His flowing language, his lucid style, his stern logic, his balanced expression, his fearless exposition, his unshakable faith in the Vedas, and other manifold qualities of his works convey an idea of his greatness that no story can adequately convey. To those who are denied the immeasurable happiness of tasting the sweetness of his works, the stories of his earthly life do convey a glimpse of his many-sided personality. Of the chief incidents in his life, there is not much variation among the several accounts entitled 'Shankara Vijayas'. Sri Shankara was born of Shivaguru and Aryamba at Kaladi in Kerala. He lost his father in the third year. He received Gayatri initiation in his fifth year. He made rapid strides in the acquisition of knowledge. -

The Key to Theosophy by H. P. Blavatsky

Theosophical University Press Online Edition THE KEY TO THEOSOPHY BY H. P. BLAVATSKY Being a Clear Exposition, in the Form of Question and Answer, of the ETHICS, SCIENCE, AND PHILOSOPHY for the Study of which The Theosophical Society has been Founded. Originally published 1889. Theosophical University Press electronic version ISBN 1- 55700-046-8 (print version also available). Due to current limitations in the ASCII character set, and for ease of searching, no diacritical marks appear in this electronic version of the text. Dedicated by "H. P. B." To all her Pupils that They may Learn and Teach in their turn. CONTENTS PREFACE SECTION 1: THEOSOPHY AND THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY (28K) ● The Meaning of the Name ● The Policy of the Theosophical Society ● The Wisdom-Religion Esoteric in all Ages ● Theosophy is not Buddhism SECTION 2: EXOTERIC AND ESOTERIC THEOSOPHY (44K) ● What the Modern Theosophical Society is not ● Theosophists and Members of the "T. S." ● The Difference between Theosophy and Occultism ● The Difference between Theosophy and Spiritualism ● Why is Theosophy accepted? SECTION 3: THE WORKING SYSTEM OF THE T. S. (22K) ● The Objects of the Society ● The Common Origin of Man ● Our other Objects ● On the Sacredness of the Pledge SECTION 4: THE RELATIONS OF THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY TO THEOSOPHY (15K) ● On Self-Improvement ● The Abstract and the Concrete SECTION 5: THE FUNDAMENTAL TEACHINGS OF THEOSOPHY (39K) ● On God and Prayer ● Is it Necessary to Pray? ● Prayer Kills Self-Reliance ● On the Source of the Human Soul ● The Buddhist -

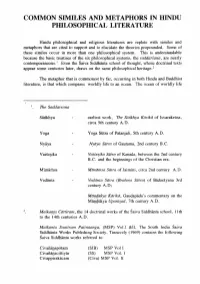

Common Similes and Metaphors in Hindu Pidlosopidcal Literature

COMMON SIMILES AND METAPHORS IN HINDU PIDLOSOPIDCAL LITERATURE Hindu philosophical and religious literatures are replete with similes and metaphors that are cited to support and to elucidate the theories propounded. Some of these similes occur in more than one philosophical system. This is understandable because the basic treatises of the six philosophical systems, the saddarsana, are nearly contemporaneous. I Even the Saiva Siddhanta school of thought, whose doctrinal texts appear some centuries later, draws on the same philosophical heritage. 2 The metaphor that is commonest by far, occurring in both Hindu and Buddhist literature, is that which compares worldly life to an ocean. The ocean of worldly life The Saddarsana Sarikhya earliest work, The Sankhya Karika of Isvarakrsna, circa 5th century A. D. Yoga Yoga Siitra of Patanjali, 5th century A.D. Nyaya Nyaya Surra of Gautama, 2nd century B.C. Vaisesika Yaisesika Surra of Kanada, between the 2nd century B.C. and the beginnings of the Christian era. Mimarnsa Mtmamsa Surra of Jaimini, circa 2nd century A.D. Vedanta Vedanm Surra (Brahm a Siirra) of Badarayana 3rd century A.D; MtitujuJ..ya Karika, Gaudapada's commentary on the Mal}9ukya Upanisad, 7th century A.D. Maikanta Cattiram, the 14 doctrinal works of the Saiva Siddhanta school, 1 Ith to the 14th centuries A.D. Maikanta Saatiram Patinaangu, (MSP) VoU &Il, The South India Saiva Siddhanta Works Publishing Society. Tinnevely (1969) contains the following Saiva Siddhanta works referred to: Civananapotam (S18) MSP Vol I Civafianacitti yar (SS) MSP Vol. I Civappirakacam (Civa) MSP Vol. n COMMON SIMILES AND METAPHORS 29 has to be 'crossed', the root -tr; 'to cross' being often used in this context." And one has to get to the other 'shore', para, which in the context means mokra 'liberation'.