Surveillance, Security, & Democracy in a Post-COVID World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hong Kong SAR

China Data Supplement November 2006 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC 30 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership 37 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries 47 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations 50 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR 54 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR 61 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan 65 Political, Social and Economic Data LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 November 2006 The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU Jen-Kai Abbreviations and Explanatory Notes CCP CC Chinese Communist Party Central Committee CCa Central Committee, alternate member CCm Central Committee, member CCSm Central Committee Secretariat, member PBa Politburo, alternate member PBm Politburo, member Cdr. Commander Chp. Chairperson CPPCC Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference CYL Communist Youth League Dep. P.C. Deputy Political Commissar Dir. Director exec. executive f female Gen.Man. General Manager Gen.Sec. General Secretary Hon.Chp. Honorary Chairperson H.V.-Chp. Honorary Vice-Chairperson MPC Municipal People’s Congress NPC National People’s Congress PCC Political Consultative Conference PLA People’s Liberation Army Pol.Com. -

Asia, International Drug Trafficking, and Us-China Counternarcotics

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION CENTER FOR NORTHEAST ASIAN POLICY STUDIES ASIA, INTERNATIONAL DRUG TRAFFICKING, AND U.S.-CHINA COUNTERNARCOTICS COOPERATION Zhang Yong-an Associate Professor and Associate Dean, College of Liberal Arts; and Executive Director, David F. Musto Center for Drug Policy Studies Shanghai University February 2012 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington D.C. 20036-2188 Tel: (202)797-6000 Fax: (202)797-2485 http://www.brookings.edu 1. Introduction The end of the Cold War may have heralded an end to certain tensions, but among other unforeseen effects it also precipitated a significant increase in the flow of illegal drugs across traditional national boundaries. International travel has become easier in an increasingly borderless world, and―although international drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) have never respected national boundaries―newly globalized markets for drug production and exportation, along with changing patterns of consumption in some societies, have had an enormous impact on drug trafficking. In short, the global market for illicit drugs, and the capacity of providers to deliver to this market, is expanding inexorably around the world. What was once called “the American disease”1 has become a global one. 2 The international community first took an interest in the Asian drug trade at the beginning of the 20th century. The Shanghai Opium Commission in 1909 was the first attempt at regulating drug trade in the region, as countries including the United States, Great Britain, China, Japan, and Russia convened to discuss the growing trafficking of opium. Since then, numerous measures have been adopted by individual countries and collectively to curb the illegal drug trade. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

3/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 30 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 41 Bibliography of Articles on the PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and on Taiwan UWE KOTZEL / LIU JEN-KAI / CHRISTINE REINKING / GÜNTER SCHUCHER 43 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 3/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 -

CASCC Via Bogino 9 101 23 Tufm 10144 Turin Personal Data

Home A~klress CASCC Corso Regina Margherita 209 Via Bogino 9 (clo Gallone) 10123 Tufm 10144 Turin ltaly ltaly E-M.TUJ~O.~P~.~H'@L'CLF(%: CCI Phane: 3494645470 Personal data Date and piace of birth: 24 August 1975, Naples Citizenship: Italian October 2W9 -Febtuary 2010 Guest Lecturer in Contemporary Chinese Studies Bayerische Juliu*Maxidians-Universitat WQrzburg, Germany July 2008 - current Researcher Centre of Advanced Studies on Contemporary China (CASCC) Turin, ltaly October 2007 -~uly2008 Guest Lecturer in Contemporary Chinese Studies (with a W1 rank of J~mbqwfesswin) Bayerische Julius-Maximlians-Universitat WOrzburg, Germany January - October 2007 Researcher Swedish Research Coundl - Vetenskapsridet Stockholm Septenber 2004 -September 2006 Postdoctoral research fellow Centre for East and South-East Asian Studies Lund University, Sweden November 2005 Visiting fellow Institute for Criminal Law, CASS, Eleijing k~ard~2003 - ~ugust20w Research assistant to Professor Paala Paderni, Italian Embassy in Beijing. March - July 2004 Research assistant to Professor Paola Paderni, Univers~tadegli Studi "L'Orientalev, Naples 98 January 2003 - hgust 2004. Research assistant within a prqect on the implementation of marriage law in China, funded by the Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR), Rome May 2002 Visiting PhD candidate French Centre for Research on Contemporary China Hong Kong January 2002 - March 2003 Research assistant for Prof. Paola Paderni. Tutoring of undergraduate students Universita degli Studi *L'OrientaleM,Naples May 2001 Vsiting PhD candidate Law School, Renmin Daxue, Beijing Teaching Criminal Justice in Contemporary China (B.A.) Human Rights in Contemporary China (B.A.) Power in transformation. The Chinese Communist Party (B.A.) Power, Punishment and the Law in China (M.A.) Bayerische Julius-Maximilians Universitat, Wurzburg Academic year 2008-09 How to find the law. -

Chin1821.Pdf

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1x0nd955 No online items Finding Aid for the China Democracy Movement and Tiananmen Incident Archives, 1989-1993 Processed by UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections UCLA Library Special Collections staff Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2009 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. 1821 1 Descriptive Summary Title: China Democracy Movement and Tiananmen Incident Archives Date (inclusive): 1989-1993 Collection number: 1821 Creator: Center for Chinese Studies and the Center for Pacific Rim Studies, UCLA Extent: 22 boxes (11 linear ft.)1 oversize box. Abstract: The present finding aid represents the fruits of a multiyear collaborative effort, undertaken at the initiative of then UCLA Chancellor Charles Young, to collect, collate, classify, and annotate available materials relating to the China Democracy Movement and tiananmen crisis of 1989. These materials---including, inter alia, thousands of documents, transcribed radio broadcasts, local newspaper and journal articles, wall posters, electronic communications, and assorted ephemeral sources, some in Chinese and some in English---provide a wealth of information for scholars, present and future, who wish to gain a better understanding of the complex, swirling forces that surrounded the extraordinary "Beijing Spring" of 1989 and its tragic denouement. The scholarly community is indebted to those who have collected and arranged this archive of materials about the China Democracy Movement and Tiananmen Incident Archives. -

The CCP Central Committee's Leading Small Groups Alice Miller

Miller, China Leadership Monitor, No. 26 The CCP Central Committee’s Leading Small Groups Alice Miller For several decades, the Chinese leadership has used informal bodies called “leading small groups” to advise the Party Politburo on policy and to coordinate implementation of policy decisions made by the Politburo and supervised by the Secretariat. Because these groups deal with sensitive leadership processes, PRC media refer to them very rarely, and almost never publicize lists of their members on a current basis. Even the limited accessible view of these groups and their evolution, however, offers insight into the structure of power and working relationships of the top Party leadership under Hu Jintao. A listing of the Central Committee “leading groups” (lingdao xiaozu 领导小组), or just “small groups” (xiaozu 小组), that are directly subordinate to the Party Secretariat and report to the Politburo and its Standing Committee and their members is appended to this article. First created in 1958, these groups are never incorporated into publicly available charts or explanations of Party institutions on a current basis. PRC media occasionally refer to them in the course of reporting on leadership policy processes, and they sometimes mention a leader’s membership in one of them. The only instance in the entire post-Mao era in which PRC media listed the current members of any of these groups was on 2003, when the PRC-controlled Hong Kong newspaper Wen Wei Po publicized a membership list of the Central Committee Taiwan Work Leading Small Group. (Wen Wei Po, 26 December 2003) This has meant that even basic insight into these groups’ current roles and their membership requires painstaking compilation of the occasional references to them in PRC media. -

How the Chinese Communist Party Manages Its Coercive Leaders* Yuhua Wang†

625 Empowering the Police: How the Chinese Communist Party Manages Its Coercive Leaders* Yuhua Wang† Abstract How does the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) secure the loyalty of its coer- cive leaders, and its public security chiefs in particular, in the face of numer- ous domestic protests every year? This article presents the first quantitative analysis of contemporary China’s coercive leaders using an original data set of provincial public security chiefs and public security funding during the reform era. I demonstrate that the CCP, owing to its concern for regime sta- bility, has empowered the public security chiefs by incorporating them into the leadership team. Empowered public security chiefs then have stronger bargaining power over budgetary issues. I rely on fieldwork, qualitative interviews and an analysis of Party documents to complement my statistical analysis. The findings of this analysis shed light on the understanding of regime durability, contentious politics and the bureaucracy in China. Keywords: public security chiefs; leadership team; coercion; public security funding; Chinese Communist Party; pork barrel In Egypt in 2011, the military generals decided to side with the protestors even though Mr Mubarak had ordered them to open fire. That same year in Libya, it was reported that soldiers from the Libyan army had refused orders to open fire on anti-regime demonstrators, while pilots flew their aircraft abroad. However, coercive leaders in China, including military officials and police chiefs, have remained loyal to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the face of domestic revolts. How does the CCP secure the loyalty of its coercive leaders? The answer has important implications for explaining the resilience of the Chinese authoritarian state.1 Despite the importance of coercion in sustaining regime stability, very few studies, and even fewer quantitative studies, have been conducted on coercive * The author wants to thank Carl Minzner for helpful comments. -

Economic and Financial Crimes

People’s Republic of China: Economic and Financial Crimes September 2002 LL File No. 2002-13494 LRA-D-PUB-000157 The Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Directorate (202) 707-5080 (phone) • (866) 550-0442 (fax) • [email protected] • http://www.law.gov This report is provided for reference purposes only. It does not constitute legal advice and does not represent the official opinion of the United States Government. The information provided reflects research undertaken as of the date of writing. It has not been updated. 2002-13494 LAW LIBRARY OF CONGRESS PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL CRIMES The People’s Republic of China extensively revised its Criminal Law in 1997 to include a wide variety of crimes involving illegal economic and financial activities. In terms of scope, organization, and overall clarity, the Law might be said to represent an advance in rule by law, even if not rule of law. However, the Chinese Communist Party still dominates the criminal justice system in the PRC; in particular, through the power of its Central Discipline Inspection Commission to investigate and determine whether Party members should be subject to criminal punishment for alleged offenses. This seems to result in differential application of the Law–between Party members and non-Party members, between Party members with powerful connections and those without, and between Party members whose behavior is singled out to serve as a warning to others and those who may be left untouched because they possess highly sensitive information about or are intimately connected with the top leadership. -

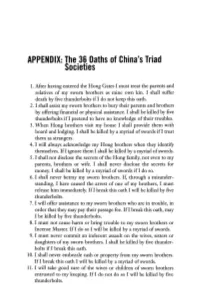

APPENDIX: the 36 Oaths of China's Triad Societies

APPENDIX: The 36 Oaths of China's Triad Societies 1. Mter having entered the Hong Gates I must treat the parents and relatives of my sworn brothers as mine own kin. I shall suffer death by five thunderbolts if I do not keep this oath. 2. I shall assist my sworn brothers to bury their parents and brothers by offering financial or physical assistance. I shall be killed by five thunderbolts if I pretend to have no knowledge of their troubles. 3. When Hong brothers visit my house I shall provide them with board and lodging. I shall be killed by a myriad of swords if I treat them as strangers. 4. I will always acknowledge my Hong brothers when they identify themselves. If I ignore them I shall be killed by a myriad of swords. 5. I shall not disclose the secrets of the Hong family, not even to my parents, brothers or wife. I shall never disclose the secrets for money. I shall be killed by a myriad of swords if I do so. 6. I shall never betray my sworn brothers. If, through a misunder standing, I have caused the arrest of one of my brothers, I must release him immediately. If I break this oath I will be killed by five thunderbolts. 7. I will offer assistance to my sworn brothers who are in trouble, in order that they may pay their passage fee. If I break this oath, may I be killed by five thunderbolts. 8. I must not cause harm or bring trouble to my sworn brothers or Incense Master. -

Data Supplement

2/2006 Data Supplement PR China Hong Kong SAR Macau SAR Taiwan Institut für Asienkunde Hamburg CHINA aktuell Journal of Current Chinese Affairs Data Supplement People’s Republic of China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: Institute of Asian Affairs Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax:(040)4107945 Contributors: Uwe Kotzel Dr. Liu Jen-Kai Christine Reinking Dr. Günter Schucher Dr. Margot Schüller Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 3 The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC LIU JEN-KAI 22 Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership LIU JEN-KAI 27 PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries LIU JEN-KAI 32 PRC Laws and Regulations LIU JEN-KAI 34 Hong Kong SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 36 Macau SAR Political Data LIU JEN-KAI 39 Taiwan Political LIU JEN-KAI 41 CHINA aktuell Data Supplement - 3 - 2/2006 Dep.Dir.: CHINESE COMMUNIST Li Jianhua 03/07 PARTY Li Zhiyong 05/07 The Main National Ouyang Song 05/08 Shen Yueyue (f) CCa 03/01 Leadership of the Sun Xiaoqun 00/08 Wang Dongming 02/10 CCP CC General Secretary Zhang Bolin (exec.) 98/03 PRC Hu Jintao 02/11 Zhao Hongzhu (exec.) 00/10 Zhao Zongnai 00/10 Liu Jen-Kai POLITBURO Sec.-Gen.: Li Zhiyong 01/03 Standing Committee Members Propaganda (Publicity) Department Hu Jintao 92/10 Dir.: Liu Yunshan PBm CCSm 02/10 Huang Ju 02/11 Dep.Dir.: Jia Qinglin 02/11 Gao Junliang 00/10 Li Changchun 02/11 Guo Yiqiang 04/05 (Changes are underlined) Luo -

And Chih-Yu Shih

Cambridge University Press 0521819792 - China’s Use of Military Force: Beyond the Great Wall and the Long March Andrew Scobell Index More information Index Academyof MilitarySciences 29, 35, Chai Chengwen 82, 87, 91, 229, 231, 175, 218–19 234 active defense 28, 31, 34–5, 92, 190 Chen Boda 100–1, 103, 106 Adelman, Jonathan (and Chih-Yu Shih) Chen Jian 201, 207–8, 218, 228–31, xi, 200, 207, 211, 229, 242 233–5, 242, 246 Allison, Graham 184, 261 Chen Shuibian 172–3, 189 Anti-Japanese Political and Military Chen Xianhua 146 University( see Kangda) Chen Xitong 148, 152, 165 Anti-Japanese War (see Japan) Chen Yi 53, 100 Chen Yun 83, 131, 145–6, 232 Ba Zhongtan 188 Chen Zaidao 102–6, 239 banners (Manchu) 43, 69, 217, 226–7 Cheng Hsiao-shih xiii, 220, 224 Beijing Massacre (see Tiananmen, Chi Haotian 53, 64, 79, 146, 150, 152, Tiananmen [Square] Massacre) 156–7, 163, 166, 228 Belgrade embassybombing (1999) 172, Chiang Kai-shek 43–4, 55, 60–2, 70, 174, 187, 191 224 Berger, Thomas 5, 200, 202, 207 “China threat” xi, 1, 19 Betts, Richard K. xii, 178, 196–7, 199, Chinese Communist Party(CCP) xii, 204, 249, 259, 263–4 6–7, 10, 26–7, 40, 46, 49, 52, 55, Bo Yibo 82, 145, 148, 231 58–9, 62, 64, 70, 75, 79, 95–7, boat people 122 100–1, 111–12, 120, 128–30, Buddhism (Buddha) 21, 95, 210 132–3, 144–50, 164, 166–7, 174, 178, 192, 194–5, 224 Central Cultural Revolution Group Politburo (Political Bureau) (CCRG) 96–100, 102–3, 105, full Politburo 53, 65, 79, 83, 87, 98, 107, 115 101, 123, 126, 128, 130–1, 175, Central MilitaryCommission (CMC) 29, 243, 246, 255, 258, 261 49, 52, 63–4, 66–7, 71, 73–4, 79, Politburo Standing Committee 88, 97–8, 100–2, 107, 110, 126, 65–6, 82, 84, 148–9, 151–2, 158, 130, 133, 140, 145–6, 149, 152, 173, 176–7, 183, 252 155–6, 163, 166, 173, 175–6, Chinese People’s Volunteers (CPV) 42, 181, 188, 250, 258, 261 80, 84, 234–5 293 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521819792 - China’s Use of Military Force: Beyond the Great Wall and the Long March Andrew Scobell Index More information Index Christensen, Thomas J.