A HRC 28 69-ES.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of Idps As a Result 0.Pdf

A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of IDPs as a Result About Syrians for Truth and Justice-STJ Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) is an independent, nongovernmental organization whose members include Syrian human rights defenders, advocates and academics of different backgrounds and nationalities. The initiative strives for SYRIA, where all Syrian citizens (males and females) have dignity, equality, justice and equal human rights . 1 A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of IDPs as a Result A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of IDPs as a Result A flash report highlighting the bombardment on the western and eastern countryside of Daraa from 15 to 20 June 2018 2 A Violent Military Escalation on Daraa, and Waves of IDPs as a Result Preface With blatant disregard of all the warnings of the international community and UN, pro- government forces launched a major military escalation against Daraa Governorate, as from 15 to 20 June 2018. According to STJ researchers, many eyewitnesses and activists from Daraa, Syrian forces began to mount a major offensive against the armed opposition factions held areas by bringing reinforcements from various regions of the country a short time ago. The scale of these reinforcements became wider since June 18, 2018, as the Syrian regime started to send massive military convoys and reinforcements towards Daraa . Al-Harra and Agrabaa towns, as well as Kafr Shams city located in the western countryside of Daraa1, have been subjected to artillery and rocket shelling which resulted in a number of civilian causalities dead or wounded. Daraa’s eastern countryside2 was also shelled, as The Lajat Nahitah and Buser al Harir towns witnessed an aerial bombardment by military aircraft of the Syrian regular forces on June 19, 2018, causing a number of civilian casualties . -

ASOR Syrian Heritage Initiative (SHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria1 NEA-PSHSS-14-001

ASOR Syrian Heritage Initiative (SHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria1 NEA-PSHSS-14-001 Weekly Report 2 — August 18, 2014 Michael D. Danti Heritage Timeline August 16 APSA website released a video and a short report on alleged looting at Deir Turmanin (5th Century AD) in Idlib Governate. SHI Incident Report SHI14-018. • DGAM posted a report on alleged vandalism/looting and combat damage sustained to the Roman/Byzantine Beit Hariri (var. Zain al-Abdeen Palace) of the 2nd Century AD in Inkhil, Daraa Governate. SHI Incident Report SHI14-017. • Heritage for Peace released its weekly report Damage to Syria’s Heritage 17 August 2014. August 15 DGAM posts short report Burning of the Historic Noria Gaabariyya in Hama. Cf. SHI Incident Report SHI14-006 dated Aug. 9. DGAM report provides new photos of the fire damage. SHI Report Update SHI14-006. August 14 Chasing Aphrodite website posted an article entitled Twenty Percent: ISIS “Khums” Tax on Archaeological Loot Fuels the Conflicts in Syria and Iraq featuring an interview between CA’s Jason Felch and Dr. Amr al-Azm of Shawnee State University. • Damage to a 6th century mosaic from al-Firkiya in the Maarat al-Numaan Museum. Source: Smithsonian Newsdesk report. SHI Incident Report SHI14-016. • Aleppo Archaeology website posted a video showing damage in the area south of the Aleppo Citadel — much of the damage was caused by the July 29 tunnel bombing of the Serail by the Islamic Front. https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?v=739634902761700&set=vb.4596681774 25042&type=2&theater SHI Incident Report Update SHI14-004. -

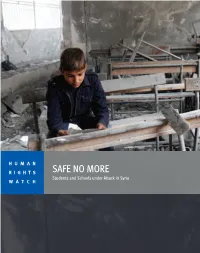

Safe No More: Students and Schools Under Attack in Syria

HUMAN RIGHTS SAFE NO MORE Students and Schools under Attack in Syria WATCH Safe No More Students and Schools under Attack in Syria Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0183 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2013 ISBN: 978-1-62313-0183 Safe No More Students and Schools under Attack in Syria Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................. -

Commentary on the EASO Country of Origin Information Reports on Syria (December 2019 – May 2020) July 2020

Commentary on the EASO Country of Origin Information Reports on Syria (December 2019 – May 2020) July 2020 1 © ARC Foundation/Dutch Council for Refugees, June 2020 ARC Foundation and the Dutch Council for Refugees publications are covered by the Create Commons License allowing for limited use of ARC Foundation publications provided the work is properly credited to ARC Foundation and the Dutch Council for Refugees and it is for non- commercial use. ARC Foundation and the Dutch Council for Refugees do not hold the copyright to the content of third party material included in this report. ARC Foundation is extremely grateful to Paul Hamlyn Foundation for its support of ARC’s involvement in this project. Feedback and comments Please help us to improve and to measure the impact of our publications. We’d be most grateful for any comments and feedback as to how the reports have been used in refugee status determination processes, or beyond: https://asylumresearchcentre.org/feedback/. Thank you. Please direct any questions to [email protected]. 2 Contents Introductory remarks ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Key observations ................................................................................................................................................ 5 General methodological observations and recommendations ......................................................................... 9 Comments on any forthcoming -

Governance in Daraa, Southern Syria: the Roles of Military and Civilian Intermediaries

Governance in Daraa, Southern Syria: The Roles of Military and Civilian Intermediaries Abdullah Al-Jabassini Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 4 November 2019 2019/15 © European University Institute 2019 Content and individual chapters © Abdullah Al-Jabassini, 2019 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2019/15 4 November 2019 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Governance in Daraa, Southern Syria: The Roles of Military and Civilian Intermediaries Abdullah Al-Jabassini* * Abdullah Al-Jabassini is a PhD candidate in International Relations at the University of Kent. His doctoral research investigates the relationship between tribalism, rebel governance and civil resistance to rebel organisations with a focus on Daraa governorate, southern Syria. He is also a researcher for the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria project at the Middle East Directions Programme of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. -

“We've Never Seen Such Horror”

Syria HUMAN “We’ve Never Seen Such Horror” RIGHTS Crimes against Humanity by Syrian Security Forces WATCH “We’ve Never Seen Such Horror” Crimes against Humanity by Syrian Security Forces Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-778-7 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org June 2011 1-56432-778-7 “We’ve Never Seen Such Horror” Crimes against Humanity by Syrian Security Forces Summary .................................................................................................................................... 1 Note on Methodology .................................................................................................................. 7 I. Timeline of Protest and Repression in Syria ............................................................................ 8 II. Crimes against Humanity and Other Violations in Daraa ...................................................... -

Security Council Distr.: General 3 August 2012

United Nations S/2012/378 Security Council Distr.: General 3 August 2012 Original: English Identical letters dated 29 May 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16-25 April and 7, 11, 14-16, 18, 21 and 24 May 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 24 May 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 12-45243 (E) 140812 150812 *1245243* S/2012/378 Annex to the identical letters dated 29 May 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Thursday, 24 May 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. At 2215 hours on 23 May 2012, an armed terrorist group planted two explosive devices in the firing range of a military barracks in Jadidah Yabus; the devices were defused by military engineers. 2. At 0430 hours an armed terrorist group opened fire on border guard post No. 212 in the district of Qalamun, wounding three personnel. 3. At 0730 hours an armed terrorist group shot and killed Lieutenant Wafiq Dib and his son, Haydar Dib, as they were leaving their house in the Fadhl district of Jadidah 'Atruz. -

“I Lost My Dignity”: Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in the Syrian Arab Republic

A/HRC/37/CRP.3 Distr.: Restricted 8 March 2018 English and Arabic only Human Rights Council Thirty-seventh session 26 February – 23 March 2018 Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention. “I lost my dignity”: Sexual and gender-based violence in the Syrian Arab Republic Conference room paper of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic Summary Sexual and gender-based violence against women, girls, men, and boys has been a persistent issue in Syria since the uprising in 2011. Parties to the conflict resort to sexual violence as a tool to instil fear, humiliate and punish or, in the case of terrorist groups, as part of their enforced social order. While the immense suffering induced by these practices impacts Syrians from all backgrounds, women and girls have been disproportionally affected, victimised on multiple grounds, irrespective of perpetrator or geographical area. Government forces and associated militias have perpetrated rape and sexual abuse of women and girls and occasionally men during ground operations, house raids to arrest protestors and perceived opposition supporters, and at checkpoints. In detention, women and girls were subjected to invasive and humiliating searches and raped, sometimes gang- raped, while male detainees were most commonly raped with objects and sometimes subjected to genital mutilation. Rape of women and girls was documented in 20 Government political and military intelligence branches, and rape of men and boys was documented in 15 branches. Sexual violence against females and males is used to force confessions, to extract information, as punishment, as well as to terrorise opposition communities. -

Report Mapping Southern Syria's Armed Opposition

Report Mapping Southern Syria’s Armed Opposition Osama al-Koshak * Al Jazeera Centre for Studies 13 October 2015 Tel: +974-40158384 [email protected] http://studies.aljazeera.n [AlJazeera] Abstract Syrian opposition forces in Daraa province, located in the country’s south, have maintained their constant military advancement without any significant defeats, and now control sixty-five per cent of the province. Further, they are attempting to secure territorial contiguity with western Damascus. Daraa is different from other provinces due to several particularities, notably: singularity of support sources, a sensitive geopolitical location as well as geographic isolation from the other areas of the revolution, Jordan’s strict control of its borders and the absence of internal and ideological conflicts seen in northern Syria’s provinces. The Southern Front, consisting of a loose assembly of forty-nine factions, has taken lead of the military scene in the province. It is considered the most prominent force on the scene, with the global Islamist jihadist forces, e.g., al-Nusra Front and other local forces, such as the Islamic Muthanna Movement and Ahrar al-Sham, next in the military order. Daraa was not isolated from the emergence of the Islamic State (IS or Daesh), although its effects were limited. Through the Military Operations Center (MOC) of the supporting countries, regional and international forces managed to greatly influence the scene in Daraa through full sponsorship of the so-called “moderate forces” in the Southern Front. Its strategy focused on using the battlefield to win political gains and weaken the regime to reach a settlement. -

Weekly Conflict Summary | 7 – 13 October 2019

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 7 – 13 OCTOBER 2019 WHOLE OF SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST | Government of Syria (GoS) shelling and aerial activity onto the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated Idleb enclave continued this week. Also, conflict activity increased in the Tal Rifaat pocket. And a suicide attack occurred in Azaz City. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | Violence continued against GoS-aligned personnel in southern Syria, including one event that targeted a joint Syrian/Russian Military Patrol near Ankhel. In central areas of the country, ISIS activity continued despite a GoS operation against a suspected ISIS base near Sokhneh town. • NORTHEAST | The combined Turkish and Syrian opposition invasion of northern Syria continued this week. Attacks against Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) continued in the Euphrates Valley. Three improvised explosive device (IED) attacks occurred in Hasakeh and Qamishli cities. Two escapes from ISIS holding facilities also occurred during the week. Figure 1: Dominant Actors’ Area of Control and Influence in Syria as of 10 October 2019. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. Also, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 6 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY 7 – 13 OCTOBER 2019 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 Conflict between Government of Syria (GoS) and the Hayyat Tahrir ash Sham (HTS)-dominated northwest continued this week, with elevated levels of GoS shelling and aerial activity impacting southern areas of the enclave. Over half of this week’s 104 events focused on the southern sub-districts of Kafr Nobel, Heish, and Madiq Castle2 (Figure 2). Figure 2: GoS Aerial Activity (Blue) and Shelling (Red) in Northwest Syria Since August 2019. Data from ACLED and The Carter Center. -

Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic*

United Nations A/HRC/28/69 General Assembly Distr.: General 5 February 2015 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-seventh session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic* Summary The present report is submitted to the Human Rights Council pursuant to Council resolution S-17/1. The violence in the Syrian Arab Republic mutated from unrest in March 2011 into internal disturbances and the emergence of a non-international armed conflict in February 2012. The conduct of an ever-increasing number of actors is characterized by a complete lack of adherence to the norms of international law. Since the outset, civilians have borne the brunt of the suffering inflicted by the warring parties. Since its establishment, the Commission of Inquiry has persistently drawn attention to the atrocities committed across the country. In the present report, the Commission charts the major trends and patterns of human rights and humanitarian law violations perpetrated from March 2011 to January 2015, and draws from more than 3,556 interviews with victims and eyewitnesses in and outside of the country, collected since September 2011. Taking stock of international actions and inaction, the report is intended to re- emphasize the dire situation of the Syrian people in the absence of a political solution to the conflict. The Commission stresses the urgent need for concerted and sustained international action to find a political solution to the conflict, to stop grave violations of human rights and to break the intractable cycle of impunity. -

Syria Targeting of Individuals

European Asylum Support Office Syria Targeting of individuals Country of Origin Information Report March 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Syria Targeting of individuals Country of Origin Information Report March 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-134-5 doi: 10.2847/683510 © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2019 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © 2018 European Union (photographer: Peter Biro), EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid, 13 November 2018, url (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN REPORT ON SYRIA: TARGETING OF INDIVIDUALS — 3 Acknowledgements EASO would like to acknowledge Germany, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF), Country Analysis, as the co-drafter of this report, together with the EASO COI sector. The following departments and organisations have reviewed the report: Finland, Finnish Immigration Service, Legal Service and Country Information Unit ACCORD, the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of