Syria Targeting of Individuals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United States and Russian Governments Involvement in the Syrian Crisis and the United Nations’ Kofi Annan Peace Process

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 5 No 27 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy December 2014 The United States and Russian Governments Involvement in the Syrian Crisis and the United Nations’ Kofi Annan Peace Process Ken Ifesinachi Ph.D Professor of Political Science, University of Nigeria [email protected] Raymond Adibe Department of Political Science, University of Nigeria [email protected] Doi:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n27p1154 Abstract The inability of the Syrian government to internally manage the popular uprising in the country have increased international pressure on Syria as well as deepen international efforts to resolve the crisis that has developed into a full scale civil war. It was the need to end the violent conflict in Syria that informed the appointment of Kofi Annan as the U.N-Arab League Special Envoy to Syria on February 23, 2012. This study investigates the U.S and Russian governments’ involvement in the Syrian crisis and the UN Kofi Annan peace process. The two persons’ Zero-sum model of the game theory is used as our framework of analysis. Our findings showed that the divergence on financial and military support by the U.S and Russian governments to the rival parties in the Syrian conflict contradicted the mandate of the U.N Security Council that sanctioned the Annan plan and compromised the ceasefire agreement contained in the plan which resulted in the escalation of violent conflict in Syria during the period the peace deal was supposed to be in effect. The implication of the study is that the success of any U.N brokered peace deal is highly dependent on the ability of its key members to have a consensus, hence, there is need to galvanize a comprehensive international consensus on how to tackle the Syrian crisis that would accommodate all crucial international actors. -

Syria: "Torture Was My Punishment": Abductions, Torture and Summary

‘TORTURE WAS MY PUNISHMENT’ ABDUCTIONS, TORTURE AND SUMMARY KILLINGS UNDER ARMED GROUP RULE IN ALEPPO AND IDLEB, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Cover photo: Armed group fighters prepare to launch a rocket in the Saif al-Dawla district of the Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons northern Syrian city of Aleppo, on 21 April 2013. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/4227/2016 July 2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 METHODOLOGY 7 1. BACKGROUND 9 1.1 Armed group rule in Aleppo and Idleb 9 1.2 Violations by other actors 13 2. ABDUCTIONS 15 2.1 Journalists and media activists 15 2.2 Lawyers, political activists and others 18 2.3 Children 21 2.4 Minorities 22 3. -

Télécharger Le COI Focus

COMMISSARIAT GÉNÉRAL AUX RÉFUGIÉS ET AUX APATRIDES COI Focus LIBAN La situation sécuritaire 7 août 2018 (Mise à jour) Cedoca Langue du document original : néerlandais DISCLAIMER: Ce document COI a été rédigé par le Centre de documentation et de This COI-product has been written by Cedoca, the Documentation and recherches (Cedoca) du CGRA en vue de fournir des informations pour le Research Department of the CGRS, and it provides information for the traitement des demandes d’asile individuelles. Il ne traduit aucune politique processing of individual asylum applications. The document does not contain ni n’exprime aucune opinion et ne prétend pas apporter de réponse définitive policy guidelines or opinions and does not pass judgment on the merits of quant à la valeur d’une demande d’asile. Il a été rédigé conformément aux the asylum application. It follows the Common EU Guidelines for processing lignes directrices de l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information country of origin information (April 2008). sur le pays d’origine (avril 2008) et il a été rédigé conformément aux The author has based the text on a wide range of public information selected dispositions légales en vigueur. with care and with a permanent concern for crosschecking sources. Even Ce document a été élaboré sur la base d’un large éventail d’informations though the document tries to Even though the document tries to cover all the publiques soigneusement sélectionnées dans un souci permanent de relevant aspects of the subject, the text is not necessarily exhaustive. If recoupement des sources. L’auteur s’est efforcé de traiter la totalité des certain events, people or organisations are not mentioned, this does not aspects pertinents du sujet mais les analyses proposées ne visent pas mean that they did not exist. -

45 the RESURRECTION of SYRIAN KURDISH POLITICS by Ro

THE RESURRECTION OF SYRIAN KURDISH POLITICS By Rodi Hevian* This article examines the current political landscape of the Kurdish region in Syria, the role the Kurds have played in the ongoing Syrian civil war, and intra-Kurdish relations. For many years, the Kurds in Syria were Iraqi Kurdistan to Afrin in the northwest on subjected to discrimination at the hands of the the Turkish border. This article examines the Ba’th regime and were stripped of their basic current political landscape of the Kurdish rights.1 During the 1960s and 1970s, some region in Syria, the role the Kurds have played Syrian Kurds were deprived of citizenship, in the ongoing conflict, and intra-Kurdish leaving them with no legal status in the relations. country.2 Although Syria was a key player in the modern Kurdish struggle against Turkey and Iraq, its policies toward the Kurds there THE KURDS IN SYRIA were in many cases worse than those in the neighboring countries. On the one hand, the It is estimated that there are some 3 million Asad regime provided safe haven for the Kurds in Syria, constituting 13 percent of Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and the Syria’s 23 million inhabitants. They mostly Kurdish movements in Iraq fighting Saddam’s occupy the northern part of the country, a regime. On the other hand, it cracked down on region that borders with Iraqi Kurdistan to the its own Kurds in the northern part of the east and Turkey to the north and west. There country. Kurdish parties, Kurdish language, are also some major districts in Aleppo and Kurdish culture and Kurdish names were Damascus that are populated by the Kurds. -

Iraq: Opposition to the Government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI)

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Opposition to the government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) Version 2.0 June 2021 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules • The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/99q9f2k0 Author Bailony, Reem Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Reem Bailony 2015 © Copyright by Reem Bailony 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 by Reem Bailony Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor James L. Gelvin, Chair This dissertation explores the transnational dimensions of the Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927. By including the activities of Syrian migrants in Egypt, Europe and the Americas, this study moves away from state-centric histories of the anti-French rebellion. Though they lived far away from the battlefields of Syria and Lebanon, migrants championed, contested, debated, and imagined the rebellion from all corners of the mahjar (or diaspora). Skeptics and supporters organized petition campaigns, solicited financial aid for rebels and civilians alike, and partook in various meetings and conferences abroad. Syrians abroad also clandestinely coordinated with rebel leaders for the transfer of weapons and funds, as well as offered strategic advice based on the political climates in Paris and Geneva. Moreover, key émigré figures played a significant role in defining the revolt, determining its goals, and formulating its program. By situating the revolt in the broader internationalism of the 1920s, this study brings to life the hitherto neglected role migrants played in bridging the local and global, the national and international. -

Volume XIII, Issue 21 October 30, 2015

VOLUME XIII, ISSUE 21 u OCTOBER 30, 2015 IN THIS ISSUE: BRIEFS ............................................................................................................................1 THE SWARM: TERRORIST INCIDENTS IN FRANCE By Timothy Holman .........................................................................................................3 CAUGHT BETWEEN RUSSIA, THE UNITED STATES AND TURKEY, Cars continue to burn SYRIAN KURDS FACE DILEMMA after a suicide attack By Wladimir van Wilgenburg .........................................................................................5 by the Islamic State in Beirut. THE EVOLUTION OF SUNNI JIHADISM IN LEBANON SINCE 2011 By Patrick Hoover .............................................................................................................8 Terrorism Monitor is a publication of The Jamestown Foundation. BANGLADESH ATTACKS SHOW INCREASING ISLAMIC STATE The Terrorism Monitor is INFLUENCE designed to be read by policy- makers and other specialists James Brandon yet be accessible to the general public. The opinions expressed within are solely those of the In the last six weeks, Bangladesh has been hit by a near-unprecedented series of Islamist authors and do not necessarily militant attacks targeting foreigners and local Shi’a Muslims. On September 28, an reflect those of The Jamestown Italian NGO worker, who was residing in the country, was shot and killed by attackers Foundation. on a moped as he was jogging near the diplomatic area of capital city Dhaka (Daily Star [Dhaka], September -

Iraq 2019 Human Rights Report

IRAQ 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Iraq is a constitutional parliamentary republic. The 2018 parliamentary elections, while imperfect, generally met international standards of free and fair elections and led to the peaceful transition of power from Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi to Adil Abd al-Mahdi. On December 1, in response to protesters’ demands for significant changes to the political system, Abd al-Mahdi submitted his resignation, which the Iraqi Council of Representatives (COR) accepted. As of December 17, Abd al-Mahdi continued to serve in a caretaker capacity while the COR worked to identify a replacement in accordance with the Iraqi constitution. Numerous domestic security forces operated throughout the country. The regular armed forces and domestic law enforcement bodies generally maintained order within the country, although some armed groups operated outside of government control. Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) consist of administratively organized forces within the Ministries of Interior and Defense, and the Counterterrorism Service. The Ministry of Interior is responsible for domestic law enforcement and maintenance of order; it oversees the Federal Police, Provincial Police, Facilities Protection Service, Civil Defense, and Department of Border Enforcement. Energy police, under the Ministry of Oil, are responsible for providing infrastructure protection. Conventional military forces under the Ministry of Defense are responsible for the defense of the country but also carry out counterterrorism and internal security operations in conjunction with the Ministry of Interior. The Counterterrorism Service reports directly to the prime minister and oversees the Counterterrorism Command, an organization that includes three brigades of special operations forces. The National Security Service (NSS) intelligence agency reports directly to the prime minister. -

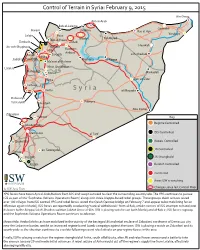

Control of Terrain in Syria: February 9, 2015

Control of Terrain in Syria: February 9, 2015 Ain-Diwar Ayn al-Arab Bab al-Salama Qamishli Harem Jarablus Ras al-Ayn Yarubiya Salqin Azaz Tal Abyad Bab al-Hawa Manbij Darkush al-Bab Jisr ash-Shughour Aleppo Hasakah Idlib Kuweiris Airbase Kasab Saraqib ash-Shadadi Ariha Jabal al-Zawiyah Maskana ar-Raqqa Ma’arat al-Nu’man Latakia Khan Sheikhoun Mahardeh Morek Markadeh Hama Deir ez-Zour Tartous Homs S y r i a al-Mayadin Dabussiya Palmyra Tal Kalakh Jussiyeh Abu Kamal Zabadani Yabrud Key Regime Controlled Jdaidet-Yabus ISIS Controlled Damascus al-Tanf Quneitra Rebels Controlled as-Suwayda JN Controlled Deraa Nassib JN Stronghold Jizzah Kurdish Controlled Contested Areas ISW is watching Changes since last Control Map by ISW Syria Team YPG forces have taken Ayn al-Arab/Kobani from ISIS and swept outward to clear the surrounding countryside. The YPG continues to pursue ISIS as part of the “Euphrates Volcano Operations Room,” along with three Aleppo-based rebel groups. These groups claim to have seized over 100 villages from ISIS control. YPG and rebel forces seized the Qarah Qawzaq bridge on February 7 and appear to be mobilizing for an oensive against Manbij. ISIS forces are reportedly conducting “tactical withdrawals” from al-Bab, amidst rumors of ISIS attempts to hand over its bases to the Aleppo Sala Jihadist coalition Jabhat Ansar al-Din. ISW is placing watches on both Manbij and al-Bab as ISIS forces regroup and the Euphrates Volcano Operations Room continues to advance. Meanwhile, Hezbollah forces have mobilized in the vicinity of the besieged JN and rebel enclave of Zabadani, northwest of Damascus city near the Lebanese border, amidst an increased regime barrel bomb campaign against the town. -

Human Rights Council Fact-Finding in S

Marauhn: Sailing Close to the Wind: Human Rights Council Fact-Finding in S SAILING CLOSE TO THE WIND: HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL FACT-FINDING IN SITUATIONS OF ARMED CONFLICT-THE CASE OF SYRIA THILO MARAUHN* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. FROM GRAFFITI IN DARA'A TO CIVIL WAR IN SYRIA ............ 402 II. SECURITY COUNCIL INACTION AND HUMAN RIGHTS ...... ..... 408 COUNCIL ACTIVISM ........................................... 408 A. Governments' Responses to the Situation in Syria ............. 409 B. Inaction of the U.N. Security Council .............. 415 C. Actions Taken by the U.N. General Assembly and the U.N. Human Rights Council ................. ....... 421 III. THE RISK OF BEING ALL-INCLUSIVE: BLURRING THE LINES.........426 A. Does the Situation in Syria Amount to a Non-International Armed Conflict? ...................... ..... 426 B. The Application ofHuman Rights Law in a Non-International Armed Conflict........................434 C. Fact-finding in Human Rights Law vs Fact-Finding with Respect to the Law ofArmed Conflict....... ............ 444 D. Does Blurringthe Lines Weaken Compliance with the Applicable Law? ................................448 IV. THE BENEFITS OF SAILING CLOSE TO THE WIND .................. 452 V. IMPROVING COMPLIANCE WITH THE LAW OF ARMED CONFLICT .............................................. 455 CONCLUSION ....................................... ....... 458 * M.Phil. (Wales), Dr. jur.utr. (Heidelberg), Professor of Public Law, International and European Law, Faculty of Law, Justus Liebig University, Giessen, Germany. The author is grateful to Charles H. B. Garraway, Colonel (ret.), United Kingdom; Nicolas Lang, Ambassador-at-Large for the Application of International Humanitarian Law, Switzerland; and Dr. Ignaz Stegmiller, Justus Liebig University, Germany for comments on earlier drafts. 401 Published by CWSL Scholarly Commons, 2013 1 California Western International Law Journal, Vol. -

Uitgelokte Aanval Op Haar Burgers.S Wij Roepen Alle Democratische

STOP TURKIJE'S OORLOG TEGEN DE KOERDEN De luchtaanvallen van Turkije hebben Afrin geraakt, een Koerdische stad in Noord-Syrie, waarbij verschillende burgers zijn gedood en verwondNiet alleen de Koerden, maar ook christenen, Arabieren en alle andere entiteiten in Afrin liggen onder zware aanvallen van TurkijeDe agressie van Turkije tegen de bewoners van Afrin is een overduidelijke misdaad tegen de mensheid; het is niet anders dan de misdaden gepleegd door ISIS. Het initiëren van een militaire aanval op een land die jou niet heeft aangevallen is een oorlogsmisdaad. Turkse jets hebben 100 plekken in Afrin als doelwit genomen, inclusief vele civiele gebieden. Ten minste 6 burgers zijn gedood en I YPG (Volksbeschermingseenheden) en 2 YPJ (Vrouwelijke Volksbeschermingseenheden) -strijders zijn gemarteld tijdens de Turkse aanvallen van afgelopen zaterdag. Ook zijn als gevolg van de aanval een aantal burgers gewond geraakt.Het binnenvallende Turkse leger voerde zaterdagmiddag omstreeks 16:00 uur luchtaanvallen uit op Afrin met de goedkeuring van Rusland. De aanvallen die door 72 straaljagers werden uitgevoerd raakten het centrum van Afrin, de districten Cindirêsê, Reco, Shera, Shêrawa en Mabeta. Ook werd het vluchtelingenkamp Rubar geraakt. Het kamp wordt bewoond door meer dan 20.000 vluchtelingen uit Syrië. Het bezettende Turkse leger en zijn terroristen probeerden eerst middels aanvallen via de grond Afrin binnen te dringen, maar zij faalden. Daarom probeerden ze de bewoners van Afrin bang te maken en ze te verdringen naar vrije gebieden van het Syrische leger / gebieden die door Turkije worden beheerd. Het inmiddels zeven jaar durende interne conflict in Syrië is veranderd in een internationale oorlog. -

Health Cluster Bulletin

HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN April 2020 Fig.: Disinfection of an IDP camp as a preventive measure to ongoing COVID-19 Turkey Cross Border Pandemic Crisis (Source: UOSSM newsletter April 2020) Emergency type: complex emergency Reporting period: 01.04.2020 to30.04.2020 12 MILLION* 2.8 MILLION 3.7 MILLION 13**ATTACKS PEOPLE IN NEED OF HEALTH PIN IN SYRIAN REFUGGES AGAINST HEALTH CARE HEALTH ASSISTANCE NWS HNO 2020 IN TURKEY (**JAN - APR 2020) (A* figures are for the Whole of Syria HNO 2020 (All figures are for the Whole of Syria) HIGHLIGHTS • During April, 135,000 people who were displaced 129 HEALTH CLUSTER MEMBERS since December went back to areas in Idleb and 38 IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS REPORTING 1 western Aleppo governorates from which they MEDICINES DELIVERED TREATMENT COURSES FOR COMMON were displaced. This includes some 114,000 people 281,310 DISEASES who returned to their areas of origin and some FUNCTIONAL HEALTH FACILITIES HERAMS 21,000 IDPs who returned to their areas of origin, FUNCTIONING FIXED PRIMARY HEALTH forcing partners to re-establish health services in 141 CARE FACILITIES some cases with limited human resources. 59 FUNCTIONING HOSPITALS • World Health Day (7 April 2020) was the day to 72 MOBILE CLINICS celebrate the work of nurses and midwives and HEALTH SERVICES2 remind world leaders of the critical role they play 750,416 CONSULTATIONS in keeping the world healthy. Nurses and other DELIVERIES ASSISTED BY A SKILLED health workers are at the forefront of COVID-19 10,127 ATTENDANT response - providing high quality, respectful 8,530 REFERRALS treatment and care. Quite simply, without nurses, 822,930 MEDICAL PROCEDURES there would be no response.