Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOF Role in Combating Transnational Organized Crime to Interagency Counterterrorism Operations

“…the threat to our nations’ security demands that we… Special Operations Command North (SOCNORTH) is a determine the potential SOF roles for countering and subordinate unified command of U.S. Special Operations diminishing these violent destabilizing networks.” Command (USSOCOM) under the operational control of U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM). SOCNORTH Rear Admiral Kerry Metz enhances command and control of special operations forces throughout the USNORTHCOM area of responsi- bility. SOCNORTH also improves DOD capability support Crime Organized Transnational in Combating Role SOF to interagency counterterrorism operations. Canadian Special Operations Forces Command (CAN- SOF Role SOFCOM) was stood up in February 2006 to provide the necessary focus and oversight for all Canadian Special Operations Forces. This initiative has ensured that the Government of Canada has the best possible integrated, in Combating led, and trained Special Operations Forces at its disposal. Transnational Joint Special Operations University (JSOU) is located at MacDill AFB, Florida, on the Pinewood Campus. JSOU was activated in September 2000 as USSOCOM’s joint educa- Organized Crime tional element. USSOCOM, a global combatant command, synchronizes the planning of Special Operations and provides Special Operations Forces to support persistent, networked, and distributed Global Combatant Command operations in order to protect and advance our Nation’s interests. MENDEL AND MCCABE Edited by William Mendel and Dr. Peter McCabe jsou.socom.mil Joint Special Operations University Press SOF Role in Combating Transnational Organized Crime Essays By Brigadier General (retired) Hector Pagan Professor Celina Realuyo Dr. Emily Spencer Colonel Bernd Horn Mr. Mark Hanna Dr. Christian Leuprecht Brigadier General Mike Rouleau Colonel Bill Mandrick, Ph.D. -

Workshop Programme

UK Arts and Humanities Research Council Research Network, Dons, Yardies and Posses: Representations of Jamaican Organised Crime Workshop 2: Spatial Imaginaries of Jamaican Organised Crime Venue: B9.22, University of Amsterdam, Roeterseiland Campus. Workshop Programme Day 1: Monday 11th June 8.45-9.00 Registration 9.00-9.15 Welcome 9.15-10.45 Organised Crime in Fiction and (Auto)Biography 10.45-11.15 Refreshment break 11.15-12.45 Organised Crime in the Media and Popular Culture 12.45-1.45 Lunch 1.45-2.45 Interactive session: The Spatial Imaginaries of Organised Crime in Post-2000 Jamaican Films 2.45-3.15 Refreshment break 3.15-5.30 Film screening / Q&A 6.30 Evening meal (La Vallade) Day 2: Tuesday 12th June 9.15-9.30 Registration 9.30-11.00 Mapping City Spaces 11.00-11.30 Refreshment break 11.30-12.30 Interactive session: Telling True Crime Tales. The Case of the Thom(p)son Twins? 12.30-1.30 Lunch 1.30-2.45 Crime and Visual Culture 1 2.45-3.15 Refreshment break 3.15-4.15 VisualiZing violence: An interactive session on representing crime and protection in Jamaican visual culture 4.15-5.15 Concluding discussion reflecting on the progress of the project, and future directions for the research 7.00 Evening meal (Sranang Makmur) Panels and interactive sessions Day 1: Monday 11th June 9.15. Organised crime in fiction and (auto)biography Kim Robinson-Walcott (University of the West Indies, Mona), ‘Legitimate Resistance: Drug Dons and Dancehall DJs as Jamaican Outlaws at the Frontier’ Lucy Evans (University of Leicester), ‘The Yardies Becomes Rudies Becomes Shottas’: Reworking Yardie Fiction in Marlon James’ A Brief History of Seven Killings’ Michael Bucknor (University of the West Indies, Mona), ‘Criminal Intimacies: Psycho-Sexual Spatialities of Jamaican Transnational Crime in Garfield Ellis’s Till I’m Laid to Rest (and Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings)’ Chair: Rivke Jaffe 11.15. -

A Massacre in Jamaica

A REPORTER AT LARGE A MASSACRE IN JAMAICA After the United States demanded the extradition of a drug lord, a bloodletting ensued. BY MATTATHIAS SCHWARTZ ost cemeteries replace the illusion were preparing for war with the Jamai- told a friend who was worried about an of life’s permanence with another can state. invasion, “Tivoli is the baddest place in illusion:M the permanence of a name On Sunday, May 23rd, the Jamaican the whole wide world.” carved in stone. Not so May Pen Ceme- police asked every radio and TV station in tery, in Kingston, Jamaica, where bodies the capital to broadcast a warning that n Monday, May 24th, Hinds woke are buried on top of bodies, weeds grow said, in part, “The security forces are ap- to the sound of sporadic gunfire. over the old markers, and time humbles pealing to the law-abiding citizens of FreemanO was gone. Hinds anxiously di- even a rich man’s grave. The most for- Tivoli Gardens and Denham Town who alled his cell phone and reached him at saken burial places lie at the end of a dirt wish to leave those communities to do so.” the house of a friend named Hugh Scully, path that follows a fetid gully across two The police sent buses to the edge of the who lived nearby. Freeman was calm, and bridges and through an open meadow, neighborhood to evacuate residents to Hinds, who had not been outside for far enough south to hear the white noise temporary accommodations. But only a three days, assumed that it was safe to go coming off the harbor and the highway. -

The Transnationalization of Garrisons in the Case of Jamaica Michelle Angela Munroe M Munroe [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-13-2013 The aD rk Side of Globalization: The Transnationalization of Garrisons in the Case of Jamaica Michelle Angela Munroe [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI13120610 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Munroe, Michelle Angela, "The aD rk Side of Globalization: The rT ansnationalization of Garrisons in the Case of Jamaica" (2013). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 996. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/996 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida THE DARK SIDE OF GLOBALIZATION: THE TRANSNATIONALIZATION OF GARRISONS IN THE CASE OF JAMAICA A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Michelle Angela Munroe 2013 To: Dean Kenneth G. Furton College of Arts and Science This dissertation, written by Michelle Angela Munroe, and entitled The Dark Side of Globalization: The Transnationalization of Garrisons in the Case of Jamaica, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Ronald W. Cox _______________________________________ Felix Martin _______________________________________ Nicol C. -

Praying Against Worldwide Criminal Organizations.Pdf

o Marielitos · Detroit Peru ------------------------------------------------- · Filipino crime gangs Afghanistan -------------------------------------- o Rathkeale Rovers o VIS Worldwide § The Corporation o Black Mafia Family · Peruvian drug cartels (Abu SayyafandNew People's Army) · Golden Crescent o Kinahan gang o SIC · Mexican Mafia o Young Boys, Inc. o Zevallos organisation § Salonga Group o Afridi Network o The Heaphys, Cork o Karamanski gang § Surenos or SUR 13 o Chambers Brothers Venezuela ---------------------------------------- § Kuratong Baleleng o Afghan drug cartels(Taliban) Spain ------------------------------------------------- o TIM Criminal o Puerto Rican mafia · Philadelphia · TheCuntrera-Caruana Mafia clan § Changco gang § Noorzai Organization · Spain(ETA) o Naglite § Agosto organization o Black Mafia · Pasquale, Paolo and Gaspare § Putik gang § Khan organization o Galician mafia o Rashkov clan § La ONU o Junior Black Mafia Cuntrera · Cambodian crime gangs § Karzai organization(alleged) o Romaniclans · Serbian mafia Organizations Teng Bunmaorganization § Martinez Familia Sangeros · Oakland, California · Norte del Valle Cartel o § Bagcho organization § El Clan De La Paca o Arkan clan § Solano organization Central Asia ------------------------------------- o 69 Mob · TheCartel of the Suns · Malaysian crime gangs o Los Miami o Zemun Clan § Negri organization Honduras ----------------------------------------- o Mamak Gang · Uzbek mafia(Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan) Poland ----------------------------------------------- -

Youth Violence and Organized Crime in Jamaica

YOUTH VIOLENCE AND ORGANIZED CRIME IN JAMAICA: CAUSES AND COUNTER-MEASURES An Examination of the Linkages and Disconnections Final Technical Report AUTHORED BY HORACE LEVY October 2012 YOUTH VIOLENCE AND ORGANIZED CRIME IN JAMAICA: CAUSES AND COUNTER-MEASURES An Examination of the Linkages and Disconnections Final Technical Report AUTHORED BY HORACE LEVY October 2012 Name of Research Institution: The University of the West Indies (UWI) – Institute of Criminal Justice and Security (ICJS) International Development Research Centre (IDRC) Grant Number: 106290-001 Country: Jamaica Research Team: – Elizabeth Ward (Principal Investigator) – Horace Levy (Consultant – PLA Specialist) – Damian Hutchinson (Research Assistant) – Tarik Weekes (Research Assistant) Community Facilitators: – Andrew Geohagen (co-lead) – Milton Tomlinson (co-lead) – Vernon Hunter – Venisha Lewis – Natalie McDonald – Ricardo Spence – Kirk Thomas – Michael Walker Administrative Staff: – Deanna Ashley (Project Manager) – Julian Moore (Research Assistant) – Andrienne Williams Gayle (Administrative Assistant) Author of Report: Horace Levy Date of Presentation to IDRC: October 2012 This publication was carried out with the support of a grant from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Canada. The opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of IDRC. CONTENTS Acknowledgements 5 Synthesis 6 Background and Research Problem 8 Objectives 10 Methodology and Activities (Project Design & Implementation) 12 Project Outputs and Dissemination 22 Project Outcomes 24 A. Research Findings 24 1. Crews and Gangs Distinguished 24 2. Case of Defence Crew becoming Criminal Gang 29 3. Violence of Individuals 30 4. Influence of the Shower Posse 31 5. The Tivoli Gardens Incursion and Central Authority 32 6. Leadership 34 7. Gang Members and Legal Alternatives 34 8. Women 34 9. -

Coke, Christoper Michael Plea

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE AUGUST 31, 2011 ELLEN DAVIS, CARLY SULLIVAN, JERIKA RICHARDSON PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 JAMAICAN DRUG LORD CHRISTOPHER MICHAEL COKE PLEADS GUILTY IN MANHATTAN FEDERAL COURT PREET BHARARA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, announced that CHRISTOPHER MICHAEL COKE, the leader of the Jamaica-based international criminal organization, "Shower Posse," also known as the "Presidential Click," pled guilty today to one count of racketeering conspiracy and one count of conspiracy to commit assault with a dangerous weapon in aid of racketeering. COKE was arrested by Jamaican authorities on June 22, 2010, near Kingston, Jamaica, and arrived in the Southern District of New York on June 24, 2010. COKE pled guilty before U.S. District Judge ROBERT P. PATTERSON. Manhattan U.S. Attorney PREET BHARARA stated: "For nearly two decades, Christopher Coke led a ruthless criminal enterprise that used fear, force and intimidation to support its drug and arms trafficking 'businesses.' He moved drugs and guns between Jamaica and the United States with impunity. Today's plea is a welcome conclusion to this ugly chapter of criminal history." According to the Superseding Information filed today in Manhattan federal court: Since the early 1990s, COKE led the Presidential Click, with members in Jamaica, the United States, and other countries, and controlled the Tivoli Gardens area, a neighborhood in inner- city Kingston, Jamaica. Tivoli Gardens was guarded by a group of gunmen who acted at COKE's direction. They were armed with illegally trafficked firearms from the United States, that COKE imported into Jamaica. -

Pennsylvania .Crime

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. • · Pennsylvania • .Crime. ·Commis'sion • .~ ."• 1989REPORT • • COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA • • • PENNSYLVANIA CRIME COMMISSION • 1989REPORT • 138666 • U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated In this document a~e those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the Nalionallnslitute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been • granted by ~ennsy1vania Crime Commission to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further repr~duction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission • of the copynght owner. • Printed in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania 1100 E. Hector Street Conshohocken, PA 19428 • (215) 834-1164 • PENNSYLVANIA CRIME • COMMISSION Michael}. Reilly, Esq. - Chairman Charles H. Rogovin, Esq. - Vice-Chairman • Trevor Edwards, Esq. - Commissioner James H. Manning, Jr., Esq. - Commissioner Arthur L. Coccodrilli - Commissioner* EXECUTIVE STAFF Frederick T. Martens - Executive Director G. Alan Bailey - Deputy Executive Director/Chief Counsel • Willie C. Byrd - Director of Investigations Gerald D. Rockey - SAC, Intelligence STAFF PERSONNEL Sharon L. Beerman Gino L. Lazzari Nancy B. Checket Geraldine Lyons - Student Intern • Daniel A. Chizever Doris R. Mallin Ross E. Cogan Joseph A. Martinez Thomas J. Connor Margaret A. Millhouse Terri Cram bo Russell J. Millhouse Christopher J. DeCree Edward J. Mokos Michael B. DiPietro MarkA. Morina • Joseph P. Dougherty Gertrude F. Payne William F. Foran Wasyl Polischuk J. R. Freeman Willie M. Powell Edgar Gaskin Edward M. Recke Perrise Hatcher Lois Ryals Barbara A. -

00007-2010.Pdf

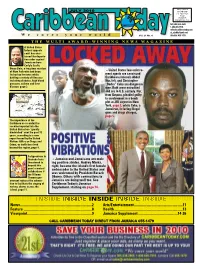

PRESORTED July 2010 STANDARD ® U.S. POSTAGE PAID MIAMI, FL PERMIT NO. 7315 Tel: (305) 238-2868 1-800-605-7516 [email protected] [email protected] We cover your world Vol. 21 No. 8 Jamaica: 655-1479 THE MULTI AWARD-WINNING NEWS MAGAZINE A United States federal appeals court has over - turned the deporta - tion order against Jamaican-born Carlyle Leslie Owen Dale, a long time resident of New York who had been ~ United States law enforce - locked up for years while ment agents are convinced battling a variety of illnesses – Caribbean nationals Abdel including diabetes, high blood Nur, left, and Christopher pressure, asthma and liver “Dudus” Coke are dangerous disease, page 3. men. Both were extradited and are in U.S. custody. Nur, from Guyana, pleaded guilty to involvement in a bomb plot at JFK airport in New York, page 2, while Coke, a Jamaican, is facing illegal guns and drugs charges, page 5. The importance of the Caribbean as a conduit for cocaine imported into the United States has “greatly diminished” over the past 15 years, according to a new report issued by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, as traffickers look beyond the region, page 8. Calypsonians in Grenada have ~ Jamaica and Jamaicans are mak - threatened to ing positive strides. Audrey Marks, boycott this right, became the island’s first female year’s carnival ambassador to the United States and celebrations if the Tillman was welcomed by President Barack Thomas gov - Obama. Others with connections to ernment reduces the subven - Jamaica are doing well too. -

Shower Posse Author: Joshua T

Organization Data Sheet – Shower Posse Author: Joshua T. Hoffman Review: Phil Williams A. When the organization was formed + brief history Under the leadership of Lester Lloyd Coke, the Shower Posse – named for its reputation of “raining” bullets on rival gangs – originated from the ghettos of Kingston, Jamaica in the late 1970s to early 1980s.1 At one point the FBI referred to the group as “the most violent and notorious criminal organization ever in America.”2 The posse was one of several posses utilized by Jamaica’s political system as tools to extort votes and provide intimidation.3 During the 1980s, the group expanded its activities to include the drug trade (ganga and crack cocaine), sending shipments of ganga to secret air strips throughout the Florida Keys.4 Still, the group was not feared in the United States until its involvement in the trafficking of cocaine. Using Jamaica as a transportation stop – moving the drugs from South America to the U.S. – the group’s operations stretched from Miami to New York (and included drug bases in more than 20 US cities, Canada, and the United Kingdom.5 B. Types of illegal activities engaged in, a. In general Drug trafficking, arms trafficking, and protection rackets b. Specific detail: types of illicit trafficking activities engaged in Drug trafficking: marijuana and cocaine C. Scope and Size a. Estimated size of network and membership Information not found. b. Countries / regions group is known to have operated in. (i.e. the group’s operating area) Many of the group’s members originated from Tivoli Gardens and other garrisons controlled by the JLP – such as the Southside.6 United States – several major cities (Miami, New York City, Seattle, etc.) Canada – greatest base of operation in Toronto (more than 20 years) UK – a splinter group known as the “President Click” operated in parts of Brixton7 D. -

The Extradition Treaty Between Jamaica and the United States: Its History and the Saga of Christopher “Dudus” Coke Kenneth L

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami Inter-American Law Review 10-1-2013 The Extradition Treaty Between Jamaica and the United States: Its History and the Saga of Christopher “Dudus” Coke Kenneth l. Lewis Jr. Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Kenneth l. Lewis Jr., The Extradition Treaty Between Jamaica and the United States: Its History and the Saga of Christopher “Dudus” Coke, 45 U. Miami Inter-Am. L. Rev. 63 (2013) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/vol45/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Inter- American Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\I\IAL\45-1\IAL102.txt unknown Seq: 1 12-FEB-14 16:46 63 The Extradition Treaty Between Jamaica and the United States: Its History and the Saga of Christopher “Dudus” Coke Kenneth L. Lewis, Jr.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ....................................... II. THE HISTORY AND PURPOSE OF THE TREATY .......... 67 R III. EXTRADITION SAGA OF CHRISTOPHER “DUDUS” COKE .70 R IV. THE JAMAICAN GOVERNMENT HAD LEGAL GROUNDS FOR REFUSING THE EXTRADITION REQUEST ........... 72 R A. Mr. Coke was a Person Defined in the Treaty and Therefore Subject to Extradition, Though Not a Citizen of the United States ...................... 72 R B. The Treaty and the Jamaican Extradition Act Provided The Jamaican Government with Defenses to the Extradition of Mr. -

Download PDF 375.04 KB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Risk Factors of Gang Membership: A Study of Community, School, Family, Peer and Individual Level Predictors Among Three South Florida Counties Karla Johanna Dhungana Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE RISK FACTORS OF GANG MEMBERSHIP: A STUDY OF COMMUNITY, SCHOOL, FAMILY, PEER AND INDIVIDUAL LEVEL PREDICTORS AMONG THREE SOUTH FLORIDA COUNTIES By KARLA JOHANNA DHUNGANA A Thesis submitted to the College of Criminology and Criminal Justice in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2009 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Karla Johanna Dhungana defended on April 24, 2009. __________________________________ Sarah Bacon Professor Directing Thesis __________________________________ William Bales Committee Member __________________________________ Brian Stults Committee Member Approved: _____________________________________ Sarah Bacon, Thesis Committee Chair, College of Criminology and Criminal Justice ______________________________________ Thomas Blomberg, Dean, College of Criminology and Criminal Justice The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I dedicate this to my twin brother and other half, Jeffrey Carlo Dhungana; after spending 22 years together two roads diverged. While his journey took him on adventures across the Americas, I found myself in Graduate School. Both eager to become Agents of Change, in following our separate paths we came to discover and realize within ourselves a similar tenacity, courage and perseverance. For the inspiration, love and support since day one and for remaining my hero, despite our physical distance, this one is for you brother! iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincerest gratitude is due to my major professor and committee chair, Dr.