Download PDF 375.04 KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States District Court District of Massachusetts

Case 1:07-cr-10240-RGS Document 292 Filed 04/15/10 Page 1 of 18 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS CRIMINAL NO. 07-10240-RGS UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. SCOTT TOWNE MEMORANDUM AND ORDER ON DEFENDANT’S MOTION TO SUPPRESS EVIDENCE AND MOTION TO DISMISS April 15, 2010 STEARNS, D.J. In these two motions, defendant Scott Towne seeks to suppress evidence seized from his home at 42 Belmont Street in East Bridgewater, Massachusetts. The search was conducted pursuant to a warrant issued by a Magistrate of the Brockton District Court. Towne contests the affiant’s showing of probable cause, and contends that, in any event, the searching officers exceeded their authority under the warrant. Towne also seeks a dismissal of the underlying indictment on grounds of outrageous government misconduct. On January 15, 2010, the court heard evidence on the motion to suppress. Counsel also presented argument on the motion to dismiss. BACKGROUND Towne and fourteen members of the Taunton chapter of the Outlaws Motorcycle Club (Outlaws) were indicted for conspiring to distribute cocaine and marihuana. The Case 1:07-cr-10240-RGS Document 292 Filed 04/15/10 Page 2 of 18 indictment was the culmination of a two-year joint federal and state investigation.1 In tandem with the indictment, search warrants were obtained by members of the investigating task force. Among the searches authorized was that of Towne’s East Bridgewater residence. The affiant who applied for and obtained the warrant was Sgt. Thomas Higginbotham of the Massachusetts State Police (MSP). THE MOTION TO SUPPRESS Findings of Fact The following facts are taken from the testimony presented at the January 15, 2010 hearing, and more particularly, the affidavit submitted in support of the search warrant. -

SOF Role in Combating Transnational Organized Crime to Interagency Counterterrorism Operations

“…the threat to our nations’ security demands that we… Special Operations Command North (SOCNORTH) is a determine the potential SOF roles for countering and subordinate unified command of U.S. Special Operations diminishing these violent destabilizing networks.” Command (USSOCOM) under the operational control of U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM). SOCNORTH Rear Admiral Kerry Metz enhances command and control of special operations forces throughout the USNORTHCOM area of responsi- bility. SOCNORTH also improves DOD capability support Crime Organized Transnational in Combating Role SOF to interagency counterterrorism operations. Canadian Special Operations Forces Command (CAN- SOF Role SOFCOM) was stood up in February 2006 to provide the necessary focus and oversight for all Canadian Special Operations Forces. This initiative has ensured that the Government of Canada has the best possible integrated, in Combating led, and trained Special Operations Forces at its disposal. Transnational Joint Special Operations University (JSOU) is located at MacDill AFB, Florida, on the Pinewood Campus. JSOU was activated in September 2000 as USSOCOM’s joint educa- Organized Crime tional element. USSOCOM, a global combatant command, synchronizes the planning of Special Operations and provides Special Operations Forces to support persistent, networked, and distributed Global Combatant Command operations in order to protect and advance our Nation’s interests. MENDEL AND MCCABE Edited by William Mendel and Dr. Peter McCabe jsou.socom.mil Joint Special Operations University Press SOF Role in Combating Transnational Organized Crime Essays By Brigadier General (retired) Hector Pagan Professor Celina Realuyo Dr. Emily Spencer Colonel Bernd Horn Mr. Mark Hanna Dr. Christian Leuprecht Brigadier General Mike Rouleau Colonel Bill Mandrick, Ph.D. -

Workshop Programme

UK Arts and Humanities Research Council Research Network, Dons, Yardies and Posses: Representations of Jamaican Organised Crime Workshop 2: Spatial Imaginaries of Jamaican Organised Crime Venue: B9.22, University of Amsterdam, Roeterseiland Campus. Workshop Programme Day 1: Monday 11th June 8.45-9.00 Registration 9.00-9.15 Welcome 9.15-10.45 Organised Crime in Fiction and (Auto)Biography 10.45-11.15 Refreshment break 11.15-12.45 Organised Crime in the Media and Popular Culture 12.45-1.45 Lunch 1.45-2.45 Interactive session: The Spatial Imaginaries of Organised Crime in Post-2000 Jamaican Films 2.45-3.15 Refreshment break 3.15-5.30 Film screening / Q&A 6.30 Evening meal (La Vallade) Day 2: Tuesday 12th June 9.15-9.30 Registration 9.30-11.00 Mapping City Spaces 11.00-11.30 Refreshment break 11.30-12.30 Interactive session: Telling True Crime Tales. The Case of the Thom(p)son Twins? 12.30-1.30 Lunch 1.30-2.45 Crime and Visual Culture 1 2.45-3.15 Refreshment break 3.15-4.15 VisualiZing violence: An interactive session on representing crime and protection in Jamaican visual culture 4.15-5.15 Concluding discussion reflecting on the progress of the project, and future directions for the research 7.00 Evening meal (Sranang Makmur) Panels and interactive sessions Day 1: Monday 11th June 9.15. Organised crime in fiction and (auto)biography Kim Robinson-Walcott (University of the West Indies, Mona), ‘Legitimate Resistance: Drug Dons and Dancehall DJs as Jamaican Outlaws at the Frontier’ Lucy Evans (University of Leicester), ‘The Yardies Becomes Rudies Becomes Shottas’: Reworking Yardie Fiction in Marlon James’ A Brief History of Seven Killings’ Michael Bucknor (University of the West Indies, Mona), ‘Criminal Intimacies: Psycho-Sexual Spatialities of Jamaican Transnational Crime in Garfield Ellis’s Till I’m Laid to Rest (and Marlon James’s A Brief History of Seven Killings)’ Chair: Rivke Jaffe 11.15. -

A Community Response

A Community Response Crime and Violence Prevention Center California Attorney General’s Office Bill Lockyer, Attorney General GANGS A COMMUNITY RESPONSE California Attorney General’s Office Crime and Violence Prevention Center June 2003 Introduction Gangs have spread from major urban areas in California to the suburbs, and even to our rural communities. Today, the gang life style draws young people from all walks of life, socio-economic backgrounds and races and ethnic groups. Gangs are a problem not only for law enforcement but also for the community. Drive-by shootings, carjackings, home invasions and the loss of innocent life have become too frequent throughout California, destroying lives and ripping apart the fabric of communities. As a parent, educator, member of law enforcement, youth or con- cerned community member, you can help prevent further gang violence by learning what a gang is, what the signs of gang involvement and gang activity are and what you can do to stem future gang violence. Gangs: A Community Response discusses the history of Califor- nia-based gangs, and will help you identify types of gangs and signs of gang involvement. This booklet includes information on what you and your community can do to prevent and decrease gang activity. It is designed to answer key questions about why kids join gangs and the types of gang activities in which they may be involved. It suggests actions that concerned individuals, parents, educators, law enforcement, community members and local government officials can take and provides additional resource information. Our hope is that this booklet will give parents, educators, law enforcement and other community members a better understand- ing of the gang culture and provide solutions to help prevent young people from joining gangs and help them to embark on a brighter future. -

A Massacre in Jamaica

A REPORTER AT LARGE A MASSACRE IN JAMAICA After the United States demanded the extradition of a drug lord, a bloodletting ensued. BY MATTATHIAS SCHWARTZ ost cemeteries replace the illusion were preparing for war with the Jamai- told a friend who was worried about an of life’s permanence with another can state. invasion, “Tivoli is the baddest place in illusion:M the permanence of a name On Sunday, May 23rd, the Jamaican the whole wide world.” carved in stone. Not so May Pen Ceme- police asked every radio and TV station in tery, in Kingston, Jamaica, where bodies the capital to broadcast a warning that n Monday, May 24th, Hinds woke are buried on top of bodies, weeds grow said, in part, “The security forces are ap- to the sound of sporadic gunfire. over the old markers, and time humbles pealing to the law-abiding citizens of FreemanO was gone. Hinds anxiously di- even a rich man’s grave. The most for- Tivoli Gardens and Denham Town who alled his cell phone and reached him at saken burial places lie at the end of a dirt wish to leave those communities to do so.” the house of a friend named Hugh Scully, path that follows a fetid gully across two The police sent buses to the edge of the who lived nearby. Freeman was calm, and bridges and through an open meadow, neighborhood to evacuate residents to Hinds, who had not been outside for far enough south to hear the white noise temporary accommodations. But only a three days, assumed that it was safe to go coming off the harbor and the highway. -

Los Angeles City Attorney Gang Division

Bate: 1 °/?/0^ Submitted rn fob HdC ^^Committae Gouneii File No: .^S Oh ~Q 1~\) Iterh Nq.l.-?— Depute:---------- !. Li LOS ANGELES CITY ATTORNEY GANG DIVISION •' > RESPONSE TO AD HOC COMMITTEE ON GANG VIOLENCE AND YOUTH DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL FILE NO. 08-0150-S1 COUNCIL FILE NO. 06-0727 AD HOC COMMITTEE ON GANG VIOLENCE AND YOUTH DEVELOPMENT, SPECIAL MEETING THURSDAY, OCTOBER 9, 2008 ROOM 1010 - CITY HALL -11:00 AM 200 NORTH SPRING STREET, LOS ANGELES, CA 90012 MEMBERS: COUNCILMEMBER TONY CARDENAS, CHAIR COUNCILMEMBER HERB J. WESSON, JR. COUNCILMEMBER JANICE HAHN COUNCILMEMBER JOS£ HUIZAR COUNCILMEMBER ED P. REYES (Adam R. Lid - Legislative Assistant - (213) 978-1076 or e-mail [email protected]) Note: For information regarding the Committee and its operations, please contact the Committee Legislative Assistant at the phone number and/or email address listed above. The Legislative Assistant may answer questions and provide materials and notice of matters scheduled before the City Council. Assistive listening devices are available at the meeting. Upon 24-hour advance notice, other accommodations, such as sign language interpretation and translation services, will be provided. Contact the Legislative Assistant listed above for the needed services. TDD is available at (213) 978-1055. FILE NO. SUBJECT (D 08-0150-S1 CONTINUED FROM 6-26-08 Motion (Alarcon - Cardenas) relative to receiving public input in regard to potential gang injunctions; requesting the City Attorney to review the process for receiving public input from Neighborhood Councils for gang injunctions; and related matters. Community Impact Statement: None Submitted DISPOSITION________________________________________________________ (2) 06-0727 CONTINUED FROM 11-3-06 Motion (Cardenas - Hahn - Reyes) relative to the City Attorney and the Los Angeles Police Department to report on gang injunctions. -

Mara Salvatrucha: the Most Dangerous Gang in America

Mara Salvatrucha: The Deadliest Street Gang in America Albert DeAmicis July 31, 2017 Independent Study LaRoche College Mara Salvatrucha: The Deadliest Street Gang in America Abstract The following paper will address the most violent gang in America: Mara Salvatrucha or MS-13. The paper will trace the gang’s inception and its development exponentially into this country. MS-13’s violence has increased ten-fold due to certain policies and laws during the Obama administration, as in areas such as Long Island, New York. Also Suffolk County which encompasses Brentwood and Central Islip and other areas in New York. Violence in these communities have really raised the awareness by the Trump administration who has declared war on MS-13. The Department of Justice under the Trump administration has lent their full support to Immigration Custom Enforcement (ICE) to deport these MS-13 gang members back to their home countries such as El Salvador who has been making contingency plans to accept this large influx of deportations of MS-13 from the United States. It has been determined by Garcia of Insight.com that MS-13 has entered into an alliance with the security threat group, the Mexican Mafia or La Eme, a notorious prison gang inside the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. The Mexican Drug Trafficking Organization [Knights Templar] peddles their drugs throughout a large MS-13 national network across the country. This MS-13 street gang is also attempting to move away from a loosely run clique or clikas into a more structured organization. They are currently attempting to organize the hierarchy by combining both west and east coast MS-13 gangs. -

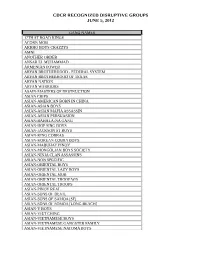

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

HISTORY of STREET GANGS in the UNITED STATES By: James C

Bureau of Justice Assistance U.S. Department of Justice NATIO N AL GA ng CE N TER BULLETI N No. 4 May 2010 HISTORY OF STREET GANGS IN THE UNITED STATES By: James C. Howell and John P. Moore Introduction The first active gangs in Western civilization were reported characteristics of gangs in their respective regions. by Pike (1873, pp. 276–277), a widely respected chronicler Therefore, an understanding of regional influences of British crime. He documented the existence of gangs of should help illuminate key features of gangs that operate highway robbers in England during the 17th century, and in these particular areas of the United States. he speculates that similar gangs might well have existed in our mother country much earlier, perhaps as early as Gang emergence in the Northeast and Midwest was the 14th or even the 12th century. But it does not appear fueled by immigration and poverty, first by two waves that these gangs had the features of modern-day, serious of poor, largely white families from Europe. Seeking a street gangs.1 More structured gangs did not appear better life, the early immigrant groups mainly settled in until the early 1600s, when London was “terrorized by a urban areas and formed communities to join each other series of organized gangs calling themselves the Mims, in the economic struggle. Unfortunately, they had few Hectors, Bugles, Dead Boys … who found amusement in marketable skills. Difficulties in finding work and a place breaking windows, [and] demolishing taverns, [and they] to live and adjusting to urban life were equally common also fought pitched battles among themselves dressed among the European immigrants. -

Police Response to Gangs: a Multi-Site Study

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Police Response to Gangs: A Multi-Site Study Author(s): Charles M. Katz; Vincent J. Webb Document No.: 205003 Date Received: April 2004 Award Number: 98-IJ-CX-0078 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Police Response to Gangs: A Multi-Site Study 1 Prepared for the National Institute of Justice by Charles M. Katz Vincent J. Webb Department of Criminal Justice and Criminology December 2003 Phoenix, Arizona 1 This research report was funded by the National Institute of Justice, Grant No. 1998-IJ-CX-0078. The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the National Institute of Justice. Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................ i Research Goals and Objectives ........................................................................................ i Research Design and Methodology.................................................................................. i Research Results and Conclusions..................................................................................ii -

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 August 24, 2020 MR. JOHN GREENEWALD JR. SUITE

U.S. Department of Justice Federal Bureau of Investigation Washington, D.C. 20535 August 24, 2020 MR. JOHN GREENEWALD JR. SUITE 1203 27305 WEST LIVE OAK ROAD CASTAIC, CA 91384-4520 FOIPA Request No.: 1374338-000 Subject: List of FBI Pre-Processed Files/Database Dear Mr. Greenewald: This is in response to your Freedom of Information/Privacy Acts (FOIPA) request. The FBI has completed its search for records responsive to your request. Please see the paragraphs below for relevant information specific to your request as well as the enclosed FBI FOIPA Addendum for standard responses applicable to all requests. Material consisting of 192 pages has been reviewed pursuant to Title 5, U.S. Code § 552/552a, and this material is being released to you in its entirety with no excisions of information. Please refer to the enclosed FBI FOIPA Addendum for additional standard responses applicable to your request. “Part 1” of the Addendum includes standard responses that apply to all requests. “Part 2” includes additional standard responses that apply to all requests for records about yourself or any third party individuals. “Part 3” includes general information about FBI records that you may find useful. Also enclosed is our Explanation of Exemptions. For questions regarding our determinations, visit the www.fbi.gov/foia website under “Contact Us.” The FOIPA Request number listed above has been assigned to your request. Please use this number in all correspondence concerning your request. If you are not satisfied with the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s determination in response to this request, you may administratively appeal by writing to the Director, Office of Information Policy (OIP), United States Department of Justice, 441 G Street, NW, 6th Floor, Washington, D.C. -

Glendale Police Department

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ClPY O!.F qL'J;9{'jJ.!JL[/E • Police 'Department 'Davit! J. tJ1iompson CfUt! of Police J.1s preparea 6y tfit. (jang Investigation Unit -. '. • 148396 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been g~Qted bY l' . Giend a e C1ty Po11ce Department • to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyright owner. • TABLEOFCON1ENTS • DEFINITION OF A GANG 1 OVERVIEW 1 JUVENILE PROBLEMS/GANGS 3 Summary 3 Ages 6 Location of Gangs 7 Weapons Used 7 What Ethnic Groups 7 Asian Gangs 8 Chinese Gangs 8 Filipino Gangs 10 Korean Gangs 1 1 Indochinese Gangs 12 Black Gangs 12 Hispanic Gangs 13 Prison Gang Influence 14 What do Gangs do 1 8 Graffiti 19 • Tattoo',;; 19 Monikers 20 Weapons 21 Officer's Safety 21 Vehicles 21 Attitudes 21 Gang Slang 22 Hand Signals 22 PROFILE 22 Appearance 22 Headgear 22 Watchcap 22 Sweatband 23 Hat 23 Shirts 23 PencHetons 23 Undershirt 23 T-Shirt 23 • Pants 23 ------- ------------------------ Khaki pants 23 Blue Jeans 23 .• ' Shoes 23 COMMON FILIPINO GANG DRESS 24 COMMON ARMENIAN GANG DRESS 25 COrvtMON BLACK GANG DRESS 26 COMMON mSPANIC GANG DRESS 27 ASIAN GANGS 28 Expansion of the Asian Community 28 Characteristics of Asian Gangs 28 Methods of Operations 29 Recruitment 30 Gang vs Gang 3 1 OVERVIEW OF ASIAN COMMUNITIES 3 1 Narrative of Asian Communities 3 1 Potential for Violence 32 • VIETNAMESE COMMUNITY 33 Background 33 Population 33 Jobs 34 Politics 34 Crimes 34 Hangouts 35 Mobility 35 Gang Identification 35 VIETNAMESE YOUTH GANGS 39 Tattoo 40 Vietnamese Background 40 Crimes 40 M.O.