Oh, Susanna: Exploring Artemisia’S Most Painted Heroine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/28/2021 10:23:11PM Via Free Access Notes to Chapter 1 671

Notes 1 Introduction. Fall and Redemption: The Divine Artist 1 Émile Verhaeren, “La place de James Ensor Michelangelo, 3: 1386–98; Summers, Michelangelo dans l’art contemporain,” in Verhaeren, James and the Language of Art, 238–39. Ensor, 98: “À toutes les périodes de l’histoire, 11 Sulzberger, “Les modèles italiens,” 257–64. ces influences de peuple à peuple et d’école à 12 Siena, Church of the Carmines, oil on panel, école se sont produites. Jadis l’Italie dominait 348 × 225 cm; Sanminiatelli, Domenico profondément les Floris, les Vaenius et les de Vos. Beccafumi, 101–02, no. 43. Tous pourtant ont trouvé place chez nous, dans 13 E.g., Bhabha, Location of Culture; Burke, Cultural notre école septentrionale. Plus tard, Pierre- Hybridity; Burke, Hybrid Renaissance; Canclini, Paul Rubens s’en fut à son tour là-bas; il revint Hybrid Cultures; Spivak, An Aesthetic Education. italianisé, mais ce fut pour renouveler tout l’art See also the overview of Mabardi, “Encounters of flamand.” a Heterogeneous Kind,” 1–20. 2 For an overview of scholarship on the painting, 14 Kim, The Traveling Artist, 48, 133–35; Payne, see the entry by Carl Van de Velde in Fabri and “Mescolare,” 273–94. Van Hout, From Quinten Metsys, 99–104, no. 3. 15 In fact, Vasari also uses the term pejoratively to The church received cathedral status in 1559, as refer to German art (opera tedesca) and to “bar- discussed in Chapter Nine. barous” art that appears to be a bad assemblage 3 Silver, The Paintings of Quinten Massys, 204–05, of components; see Payne, “Mescolare,” 290–91. -

What Does Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration Look Like? a Gripping New Show at Moma PS1 Presents Startling Answers

On View (https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/on-view) What Does Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration Look Like? A Gripping New Show at MoMA PS1 Presents Startling Answers Many of the works in the show were made by inmates in US prisons. Taylor Dafoe (https://news.artnet.com/about/taylor-dafoe-731), October 27, 2020 Installation view of Jesse Krimes, Apokaluptein 16389067 (2010–2013) in the exhibition "Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration." Courtesy of MoMA PS1. Photo: Matthew Septimus. Though many of the artists in “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration (https://bookshop.org/books/marking-time-art-in-the-age-of-mass-incarceration/9780674919228?aid=1934),” a new show open now at MoMA PS1, have been convicted of crimes, only in a few cases do we learn the details. “I don’t talk about guilt and innocence, nor do I talk about why people are in prison, unless that’s important for them in terms of how they understand their art-making,” says Nicole R. Fleetwood, who organized the exhibition of works made from within, or about, the US prison system. For her, the show is about carcerality as a systemic, not an individual, problem. “As an abolitionist, if you start playing into the logic of good/bad, innocent/guilty, you start to think about prisons as if they’re about individual decision-making, which is often how we talk about it in a broader normative public,” she says. “Prisons don’t exist because of individual decision-making. They exist as a punitive, harsh way of governing around structural inequality and systemic abuse.” Larry Cook, The Visiting Room #4 (2019). -

The Symbolism of Blood in Two Masterpieces of the Early Italian Baroque Art

The Symbolism of blood in two masterpieces of the early Italian Baroque art Angelo Lo Conte Throughout history, blood has been associated with countless meanings, encompassing life and death, power and pride, love and hate, fear and sacrifice. In the early Baroque, thanks to the realistic mi of Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi, blood was transformed into a new medium, whose powerful symbolism demolished the conformed traditions of Mannerism, leading art into a new expressive era. Bearer of macabre premonitions, blood is the exclamation mark in two of the most outstanding masterpieces of the early Italian Seicento: Caravaggio's Beheading a/the Baptist (1608)' (fig. 1) and Artemisia Gentileschi's Judith beheading Halo/ernes (1611-12)2 (fig. 2), in which two emblematic events of the Christian tradition are interpreted as a representation of personal memories and fears, generating a powerful spiral of emotions which constantly swirls between fiction and reality. Through this paper I propose that both Caravaggio and Aliemisia adopted blood as a symbolic representation of their own life-stories, understanding it as a vehicle to express intense emotions of fear and revenge. Seen under this perspective, the red fluid results as a powerful and dramatic weapon used to shock the viewer and, at the same time, express an intimate and anguished condition of pain. This so-called Caravaggio, The Beheading of the Baptist, 1608, Co-Cathedral of Saint John, Oratory of Saint John, Valletta, Malta. 2 Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith beheading Halafernes, 1612-13, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples. llO Angelo La Conte 'terrible naturalism'3 symbolically demarks the transition from late Mannerism to early Baroque, introducing art to a new era in which emotions and illusion prevail on rigid and controlled representation. -

The Collecting, Dealing and Patronage Practices of Gaspare Roomer

ART AND BUSINESS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NAPLES: THE COLLECTING, DEALING AND PATRONAGE PRACTICES OF GASPARE ROOMER by Chantelle Lepine-Cercone A thesis submitted to the Department of Art History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (November, 2014) Copyright ©Chantelle Lepine-Cercone, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the cultural influence of the seventeenth-century Flemish merchant Gaspare Roomer, who lived in Naples from 1616 until 1674. Specifically, it explores his art dealing, collecting and patronage activities, which exerted a notable influence on Neapolitan society. Using bank documents, letters, artist biographies and guidebooks, Roomer’s practices as an art dealer are studied and his importance as a major figure in the artistic exchange between Northern and Sourthern Europe is elucidated. His collection is primarily reconstructed using inventories, wills and artist biographies. Through this examination, Roomer emerges as one of Naples’ most prominent collectors of landscapes, still lifes and battle scenes, in addition to being a sophisticated collector of history paintings. The merchant’s relationship to the Spanish viceregal government of Naples is also discussed, as are his contributions to charity. Giving paintings to notable individuals and large donations to religious institutions were another way in which Roomer exacted influence. This study of Roomer’s cultural importance is comprehensive, exploring both Northern and Southern European sources. Through extensive use of primary source material, the full extent of Roomer’s art dealing, collecting and patronage practices are thoroughly examined. ii Acknowledgements I am deeply thankful to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Sebastian Schütze. -

BM Tour to View

08/06/2020 Gods and Heroes The influence of the Classical World on Art in the C17th and C18th The Tour of the British Museum Room 2a the Waddesdon Bequest from Baron Ferdinand Rothschild 1898 Hercules and Achelous c 1650-1675 Austrian 1 2 Limoges enamel tazza with Judith and Holofernes in the bowl, Joseph and Potiphar’s wife on the foot and the Triumph of Neptune and Amphitrite/Venus on the stem (see next slide) attributed to Joseph Limousin c 1600-1630 Omphale by Artus Quellinus the Elder 1640-1668 Flanders 3 4 see previous slide Limoges enamel salt-cellar of piédouche type with Diana in the bowl and a Muse (with triangle), Mercury, Diana (with moon), Mars, Juno (with peacock) and Venus (with flaming heart) attributed to Joseph Limousin c 1600- 1630 (also see next slide) 5 6 1 08/06/2020 Nautilus shell cup mounted with silver with Neptune on horseback on top 1600-1650 probably made in the Netherlands 7 8 Neptune supporting a Nautilus cup dated 1741 Dresden Opal glass beaker representing the Triumph of Neptune c 1680 Bohemia 9 10 Room 2 Marble figure of a girl possibly a nymph of Artemis restored by Angellini as knucklebone player from the Garden of Sallust Rome C1st-2nd AD discovered 1764 and acquired by Charles Townley on his first Grand Tour in 1768. Townley’s collection came to the museum on his death in 1805 11 12 2 08/06/2020 Charles Townley with his collection which he opened to discerning friends and the public, in a painting by Johann Zoffany of 1782. -

ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI ARTEMISIA ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI E Il Suo Tempo

ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI ARTEMISIA GENTILESCHI e il suo tempo Attraverso un arco temporale che va dal 1593 al 1653, questo volume svela gli aspetti più autentici di Artemisia Gentileschi, pittrice di raro talento e straordinaria personalità artistica. Trenta opere autografe – tra cui magnifici capolavori come l’Autoritratto come suonatrice di liuto del Wadsworth Atheneum di Hartford, la Giuditta decapita Oloferne del Museo di Capodimonte e l’Ester e As- suero del Metropolitan Museum di New York – offrono un’indagine sulla sua carriera e sulla sua progressiva ascesa che la vide affermarsi a Firenze (dal 1613 al 1620), Roma (dal 1620 al 1626), Venezia (dalla fine del 1626 al 1630) e, infine, a Napoli, dove visse fino alla morte. Per capire il ruolo di Artemisia Gentileschi nel panorama del Seicento, le sue opere sono messe a confronto con quelle di altri grandi protagonisti della sua epoca, come Cristofano Allori, Simon Vouet, Giovanni Baglione, Antiveduto Gramatica e Jusepe de Ribera. e il suo tempo Skira € 38,00 Artemisia Gentileschi e il suo tempo Roma, Palazzo Braschi 30 novembre 2016 - 7 maggio 2017 In copertina Artemisia Gentileschi, Giuditta che decapita Oloferne, 1620-1621 circa Firenze, Gallerie degli Uffizi, inv. 1597 Virginia Raggi Direzione Musei, Presidente e Capo Ufficio Stampa Albino Ruberti (cat. 28) Sindaca Ville e Parchi storici Amministratore Adele Della Sala Amministratore Delegato Claudio Parisi Presicce, Iole Siena Luca Bergamo Ufficio Stampa Roberta Biglino Art Director Direttore Marcello Francone Assessore alla Crescita -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic. -

NGA | 2017 Annual Report

N A TIO NAL G ALL E R Y O F A R T 2017 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Board of Trustees COMMITTEE Buffy Cafritz (as of September 30, 2017) Frederick W. Beinecke Calvin Cafritz Chairman Leo A. Daly III Earl A. Powell III Louisa Duemling Mitchell P. Rales Aaron Fleischman Sharon P. Rockefeller Juliet C. Folger David M. Rubenstein Marina Kellen French Andrew M. Saul Whitney Ganz Sarah M. Gewirz FINANCE COMMITTEE Lenore Greenberg Mitchell P. Rales Rose Ellen Greene Chairman Andrew S. Gundlach Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary of the Treasury Jane M. Hamilton Richard C. Hedreen Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Helen Lee Henderson Chairman President David M. Rubenstein Kasper Andrew M. Saul Mark J. Kington Kyle J. Krause David W. Laughlin AUDIT COMMITTEE Reid V. MacDonald Andrew M. Saul Chairman Jacqueline B. Mars Frederick W. Beinecke Robert B. Menschel Mitchell P. Rales Constance J. Milstein Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Pappajohn Sally Engelhard Pingree David M. Rubenstein Mitchell P. Rales David M. Rubenstein Tony Podesta William A. Prezant TRUSTEES EMERITI Diana C. Prince Julian Ganz, Jr. Robert M. Rosenthal Alexander M. Laughlin Hilary Geary Ross David O. Maxwell Roger W. Sant Victoria P. Sant B. Francis Saul II John Wilmerding Thomas A. Saunders III Fern M. Schad EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Leonard L. Silverstein Frederick W. Beinecke Albert H. Small President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Michelle Smith Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III United States Director Benjamin F. Stapleton III Franklin Kelly Luther M. -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 06, 2020: 01-11 Article Received: 26-04-2020 Accepted: 05-06-2020 Available Online: 13-06-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v9i6.1920 Caravaggio and Tenebrism—Beauty of light and shadow in baroque paintings Andy Xu1 ABSTRACT The following paper examines the reasons behind the use of tenebrism by Caravaggio under the special context of Counter-Reformation and its influence on later artists during the Baroque in Northern Europe. As Protestantism expanded throughout the entire Europe, the Catholic Church was seeking artistic methods to reattract believers. Being the precursor of Counter-Reformation art, Caravaggio incorporated tenebrism in his paintings. Art historians mostly correlate the use of tenebrism with religion, but there have also been scholars proposing how tenebrism reflects a unique naturalism that only belongs to Caravaggio. The paper will thus start with the introduction of tenebrism, discuss the two major uses of this artistic technique and will finally discuss Caravaggio’s legacy until today. Keywords: Caravaggio, Tenebrism, Counter-Reformation, Baroque, Painting, Religion. This is an open access article under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. 1. Introduction Most scholars agree that the Baroque range approximately from 1600 to 1750. There are mainly four aspects that led to the Baroque: scientific experimentation, free-market economies in Northern Europe, new philosophical and political ideas, and the division in the Catholic Church due to criticism of its corruption. Despite the fact that Galileo's discovery in astronomy, the Tulip bulb craze in Amsterdam, the diplomatic artworks by Peter Paul Rubens, the music by Johann Sebastian Bach, the Mercantilist economic theories of Colbert, the Absolutism in France are all fascinating, this paper will focus on the sophisticated and dramatic production of Catholic art during the Counter-Reformation ("Baroque Art and Architecture," n.d.). -

COVER NOVEMBER Prova.Qxd

52-54 Lucy Art March-Aprilcorr1_*FACE MANOPPELLO DEF.qxd 2/28/21 12:12 PM Page 52 OIfN B TooHksE, AErYt EaSn dO PFe oTpHle E BEHOLDERS n BY LUCY GORDAN (“The NIl eMwo nWdoor lNd”o)v bo y Giandomenico Tiepolo, from the Prado, Madrid. Below , bTyh eR eGmirlb irna na dt, fFroramm te he Royal Castle Museum, Warsaw affeo Barberini (1568-1644) became Pope Urban the help of Borromini, Bernini took over. The exterior, in - VIII on August 6, 1623. During his reign he ex - spired by the Colosseum and similar in appearance to the Mpanded papal territory by force of arms and advan - Palazzo Farnese, which had been constructed between 1541 tageous politicking and reformed church missions. But he and c. 1580, was completed in 1633. is certainly best remembered as a prominent patron of the When Urban VIII died, his successor Pamphili Pope In - arts on a grand scale. nocent X (r. 1644-1655) confiscated the Palazzo Barberini, Barberini funded many sculptures from Bernini: the but returned it in 1653. From then on it continued to remain first in c. 1617 the “Boy with a Dragon” and later, when the property of the Barberini family until 1949 when it was Pope, several portrait busts, but also numerous architectural bought by the Italian Government to become the art museum works including the building of the College of Propaganda it is today. But there was a problem: in 1934 the Barberinis Fide, the Fountain of the Triton in today’s Piazza Barberini, had rented a section of the building to the Army for its Offi - and the and the in St. -

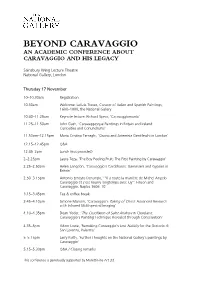

Programme for Beyond Caravaggio

BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury Wing Lecture Theatre National Gallery, London Thursday 17 November 10–10.30am Registration 10.30am Welcome: Letizia Treves, Curator of Italian and Spanish Paintings, 1600–1800, the National Gallery 10.40–11.25am Keynote lecture: Richard Spear, ‘Caravaggiomania’ 11.25–11.50am John Gash, ‘Caravaggesque Paintings in Britain and Ireland: Curiosities and Conundrums’ 11.50am–12.15pm Maria Cristina Terzaghi, ‘Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi in London’ 12.15–12.45pm Q&A 12.45–2pm Lunch (not provided) 2–2.25pm Laura Teza, ‘The Boy Peeling Fruit: The First Painting by Caravaggio’ 2.25–2.50pm Helen Langdon, ‘Caravaggio's Cardsharps: Gamesters and Gypsies in Britain’ 2.50–3.15pm Antonio Ernesto Denunzio, ‘“Il a toute la manière de Michel Angelo Caravaggio et s'est nourry longtemps avec luy”: Finson and Caravaggio, Naples 1606–10’ 3.15–3.45pm Tea & coffee break 3.45–4.10pm Simone Mancini, ‘Caravaggio's Taking of Christ: Advanced Research with Infrared Multispectral Imaging’ 4.10–4.35pm Dean Yoder, ‘The Crucifixion of Saint Andrew in Cleveland: Caravaggio’s Painting Technique Revealed through Conservation’ 4.35–5pm Adam Lowe, ‘Remaking Caravaggio’s Lost Nativity for the Oratorio di San Lorenzo, Palermo’ 5–5.15pm Larry Keith, ‘Further Thoughts on the National Gallery’s paintings by Caravaggio’ 5.15–5.30pm Q&A / Closing remarks This conference is generously supported by Moretti Fine Art Ltd. BEYOND CARAVAGGIO AN ACADEMIC CONFERENCE ABOUT CARAVAGGIO AND HIS LEGACY Sainsbury -

The Consummate Etcher and Other 17Th Century Printmakers SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY

THE CONSUMMATE EtcHER and other 17TH Century Printmakers SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY ART GALLERIES THE CONSUMMATE EtcHER and other 17th Century Printmakers A Celebration of Louise and Bernard Palitz and their association with The Syracuse University Art Galleries curated by Domenic J. Iacono CONTENTS SEptEMBER 16- NOVEMBER 14, 2013 Louise and Bernard Palitz Gallery Acknowledgements . 2 Lubin House, Syracuse University Introduction . 4 New York City, New York Landscape Prints . 6 Genre Prints . 15 Portraits . 25 Religious Prints . 32 AcKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Syracuse University Art Galleries is proud to Mr. Palitz was a serious collector of fine arts and present Rembrandt: The Consummate Etcher and after attending a Museum Studies class as a other 17th century Printmakers. This exhibition guest, offered to help realize the class lectures primarily utilizes the holdings of the Syracuse as an exhibition. We immediately began making University Art Collection and explores the impact plans to show the exhibition at both our campus of one of Europe’s most important artists on the and New York City galleries. printmakers of his day. This project, which grew out of a series of lectures for the Museum Studies The generosity of Louise and Bernard Palitz Graduate class Curatorship and Connoisseurship also made it possible to collaborate with other of Prints, demonstrates the value of a study institutions such as Cornell University and the collection as a teaching tool that can extend Herbert Johnson Museum of Art, the Dahesh outside the classroom. Museum of Art, and the Casa Buonarroti in Florence on our exhibition programming. Other In the mid-1980s, Louise and Bernard Palitz programs at Syracuse also benefitted from their made their first gift to the Syracuse University generosity including the Public Agenda Policy Art Collection and over the next 25 years they Breakfasts that bring important political figures to became ardent supporters of Syracuse University New York City for one-on-one interviews as part and our arts programs.