How Buildings Will Save the World: Using Building Energy Regulation and Energy Use Disclosure Requirements to Target Greenhouse Gas Emissions Rob Taboada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Circle Song Catalogue

Black Circle Song Catalogue Ten Vitalogy Yield Riot Act Pearl Jam L. Bolt Singles / G. Hits Other Bands Hunger Strike Once Last Exit Brain of J. Can't Keep Gone Mind Your Manners Breath Rockin’In The Free World Even Spin the Black Faithful Save You Come Back Sirens I Got ID Love Reign Oér Me Flow Circle Given to Fly Love Boat Captain Inside Job Sleeping By Myself Can't Deny Me Baba O'Riley Alive Not For You Wishlist Ghost Future Days State of Love and Breed Why Go Tremor Christ Do THe Evolution I Am Mine Infallible Trust Heart-Shaped Box Black Nothingman Low Light Thumbing My Way Them Bones Jeremy Whipping In Hiding ½ Full Would? Oceans Corduroy All Those Yesterdays All or None Black Hole SUn Porch Satan's Bed Comfortably Numb Deep Better Man Little Wing Garden Immortality I Believe in Miracles Release You've got to Hide Your Love away Go Sometimes Light Years Sad The Fixer Comes Then Goes Sleepless Nights Low Light Ceiling Animal Hail, Hail Thin Air Leaving Here Just Breathe Superblood Setting Forth Of The Light Daughter Smile Insignificance Yellow Ledbetter Amongst the Wolfmoon Rise Pages Glorified G Off He Goes Hard to Imagine Waves Dance of The Hard Sun DIsarray Dissident Red Mosquito Wash Unthought Clairvoyants Society Penguins and Butterflies W.M.A Present Tense Known Quick Escape Guaranteed Autumn Theory Blood The End Divide Rearviewmirror Never Thought I Would Rats Drive Home in the Rain Small Town Leash Indifference Crazy Mary Vs. No Code Binaural Lost Dogs Backspacer Gigaton Vedder Black Circle. -

Appetizers Kid's Menu

SOUPS & SALADS APPETIZERS BARNONE WINGS .................................................................. BAKED POTATO SOUP ............................................ 12.95 10.95 BARNONE’S SECRET RECIPE WINGS CLASSIC RECIPE, TOPPED WITH SERVED REGULAR, BARNONE, CHEDDAR AND BACON SUPER-HOT OR GARLIC/PARMESAN CIOPPINO......................................................................... 10.95 TODD’S SECRET RECIPE CHEESESTEAK EGGROLLS ...............................................11.95 WITH MISO VINAIGRETTE CHILI ...................................................................................... 9.95 CHEF MIKE’S FAVORITE BARNONE FRIED TACOS.....................................................9.95 SLOW-ROASTED PORK WITH PICKLED SOUP OF THE DAY ....................................................... 9.95 RED ONIONS AND BARNONE SALSA ASK YOUR SERVER SUNDAY GRAVY ....................................................................... 12.95 SILVIA’S WEDGE ........................................................... 9.95 MEATBALLS AND SAUSAGE, SERVED WITH A FRESH ICEBERG WEDGE WITH OUR CHEESY POLENTA CRISPS HOUSE GORGONZOLA DRESSING, BACON, TOMATO AND PICKLED RED ONIONS BARNONE SPECIAL GARLIC BREAD ..........................................................................4.95 JENNIFER’S SALAD .................................................. 15.95 BABY SPINACH, ROMAINE HEARTS, AVOCADO, VEGGIE DIP ...................................................................................4.95 ROASTED RED PEPPERS, GARLIC MUSHROOMS, AN OLD PARTY -

PDF (1.03 Mib)

The Tulane Hullabaloo I September 6, 1996 I N a | c N 。 セ ・ 5 and vocal tracks remi- disappointments of the niscent of the magic album. In a way it is still that created the original refreshing to see a musi- 1 greats, "Once," cian sacrifice pleasing . "Alive," "Even Flow" melodies to get a point and "Black." across, but "Habit" and "In My Tree" is fol- "Lukin" aren't nearly at lowed by the most the same level as, say, heavily Neil Young- "Deep" or "Blood." influenced song yet, Take "Blood" in partic- "Smile." While there ular-it is a scathing song were hints of Young which fully captures the throughout Vitalogy, torn, beaten and abused Pearl Jam makes no state of its author. It is not bones about it in this one of the most pleasing one. Vedder breaks out songs to listen to, but his harp while to artistically it is very suc- accompany Ament's cessful. "Habit" on the heavily charged guitar other hand, does not come riffs. What this song off so well. Perhaps it is brings up is the ques- because he is writing the music from anoth- reasons, none of which are the music i middle of this album, which brings up an tion as to whether or not Pearl Jam went too er person's point of view that it comes out Gossard wrote this one on his own, tht interesting point about this band. far in imitating the styles of others, and crit- watered down, or maybe it just happened to song to which Vedder hasn't at least wr Pearl Jam is above all else, an album ics will have a field day with this one. -

Roberts Rules Reluctant Rock Star Sam Roberts Caps the Year Off at the Turret JOE TURCOTTE A&E EDITOR

The Cord Weekly The tie that binds since 1926 HEAVY-WEIGHT HAWKS DRAFTED Key football players land tryouts with CFL franchises ... PAGE 6 Volume 47 Issue 1 Wednesday May 31, 2006 www.cordweekly.com Roberts rules Reluctant rock star Sam Roberts caps the year off at the Turret JOE TURCOTTE A&E EDITOR Sam Roberts’ strained voice speaks for itself, cementing the fact that staging the “Mother of All Tours” is no easy task. In be- tween setting-up in order to rock WLUSU’s Year-End Party, Roberts sat down and spoke with the Cord about the rigors of touring and the rock ‘n roll lifestyle. “I’m in preservation mode right now, but you’ve got to do what you’ve got to do,” a tired and raspy-voiced Roberts said. “It’s just about trying to keep going, man. There’s no recovery time, we get one or two days off. Tour- ing is deadly, man; touring is hard as hell. Touring is the hardest Paul Alviz thing.” SPARE SOME CHANGE? - With the UPASS expiring on May 1, Laurier students now have to scrounge together $2.25 to get around on GRT. But while the schedule may be grueling, the Canadian singer- song writer has no regrets, as he realizes that touring is essential. “Anytime you put out a new re- cord there’s only a few ways to promote it. There are interviews and the press, but you’re not really No UPASS for summer in control of that. Then you have the marketing strategies that your labels devise, and then you have Due to a number of logistical concerns, GRT and WLUSU were unable to come to terms for a summer shows, which to me [are] the best way to get your point across and extension to the popular new bus pass; both sides remain optimistic as negotations continue the only way where you’re ever fully in control.” While he remains in control MIKE BROWN students who have been sad to because there are students here make it work operationally.” over performing, Roberts ac- NEWS EDITOR see the UPASS unavailable for – there are quite a number of The major obstacle to the knowledges that he loosened-up the summer term. -

Backspacer (2009) Antologia Di Recensioni

1 PEARL JAM – BACKSPACER (2009) ANTOLOGIA DI RECENSIONI Riccardo Bertoncelli http://delrock.it 17/09/2009 Questo disco è una carezza per chi crede (e come potrebbe essere altrimenti?) che i Pearl Jam siano la più bella band della loro generazione, i soli reduci grunge ad aver raggiunto vivi e forti la matura età. Un album di bella energia, intenso inquieto, che smentisce con i fatti certe dichiarazioni soft rilasciate da Vedder nelle settimane scorse, quando aveva detto basta alla musica politica e tessuto l'elogio di una tranquilla vita in famiglia. "A volte le canzoni sono come bambini, sono puri ma poi crescono e diventano difficili da controllare, ostinati e insolenti." Può essere andata così. I PJ sono entrati in studio con l'idea di un morbido disco da quarantenni e poi si son lasciati trascinare da quello che han trovato, dai germogli di idea lanciati da Vedder e dal produttore, il primo mentore Brendan O'Brien. Eddie V sembra confermare. " Backspacer non è nato come un progetto scientifico, piuttosto come un fiore che sboccia." Di solito diffido di O'Brien, produttore con un marchio forte che tende a prevalere e a omologare. Qui però è tutta un'altra storia, perchè la banda Vedder ha un segno altrettanto forte e quel che viene non è mai banale o prevedibile; i Pearl Jam sono puro mercurio, sfuggono alle facili sottolineature, alle delimitazioni, ai luoghi comuni, con una energia nervosa che scuote, avvince e sa proiettarsi nel passato rock anche prima, molto prima, del grunge, fino ai giorni di certa acidula new wave. -

Meet NY's Wobbliest Banks

CNYB 03-02-09 A 1 2/27/2009 9:17 PM Page 1 INSIDE Still TOP STORIES making news Restaurants grow —Valerie Block as better locations on 60 Minutes’ success open up, rents fall ® Page 11 PAGE 2 Nonprofits queue for share of fed’s VOL. XXV, NO. 9 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM MARCH 2-8, 2009 PRICE: $3.00 stimulus funds PAGE 2 When your star Meet NY’s wobbliest banks name leaves: Dud investments take toll on Park Ave. Bank, Quadrangle after UM, NOT GOOD $20M Rattner PAGE 3 even parts of Milstein family’s Emigrant Bank I Nonperforming assets $30M I Total equity plus SPECIAL REPORT porary American works, all to help loan-loan reserves BY AARON ELSTEIN distinguish the bank from the com- $19M $15M petitors who line the street.Thanks in $7M for those who like to withdraw cash part to its marketing effort, Park Av- $1M or deposit checks in the presence of enue Bank’s assets quintupled after CITIZENS EMIGRANT SAVINGS BANK fine art,Park Avenue Bank is the place new management took over in 2004 COMMUNITY BANK LONG ISLAND PARK AVENUE BANK to go. A midtown branch serves as a and reached $500 million last year. THESE THREE LOCAL BANKS have soured assets overwhelming their mini-gallery, displaying everything Unfortunately, little else has gone equity and reserves, according to one recent banking benchmark. from Old Master portraits to contem- See NYC’S WORST BANKS on Page 9 Source: SNL Financial NYC TOURISM In Albany, RELAX! EVERYTHING IS ON SALE Silver’s Slogans to rebrand New York in the recession PAGE 13 good G Big Apple image problem: Some visitors are steering clear because of the economy as gold PAGE 13 G Lists of the city’s largest hotels and biggest events Speaker rises above PAGES 15, 16 weaker leaders, sets legislative agenda BUSINESS LIVES COOKED: As finance PULLING THE PLUG jobs evaporate, business is falling BY ERIK ENGQUIST Pet owners at Tommy Krisko’s forgo All-American Diner. -

Appetizers Kid's Menu

SOUPS & SALADS APPETIZERS CHEESESTEAK EGGROLLS .............................................. 11.95 WITH MISO VINAIGRETTE BAKED POTATO SOUP ..............................................9.95 CLASSIC RECIPE, TOPPED WITH SUNDAY GRAVY .......................................................................12.95 CHEDDAR AND BACON MEATBALLS AND SAUSAGE, SERVED WITH CHEESY POLENTA CRISPS BIG MIKE’S BEEF STEW ...........................................9.95 CHEF MIKE’S EMPANADAS* CHILI ......................................................................................9.95 THREE TO AN ORDER, SERVED WITH CHEF MIKE’S FAVORITE CHIPOTLE AIOLI AND GUASACACA SAUCE (AVOCADO, CILANTRO, SERRANO, PARSLEY) OAXACAN-STYLE CHICKEN SOUP .......................9.95 SPICY RED BROTH TOPPED WITH CHICKEN TINGA .............................................................................6.95 AVOCADO AND CHEESE SHORT RIB ........................................................................................7.95 SOUP OF THE DAY ....................................................... 9.95 SHREDDED PORK ..........................................................................6.95 ASK YOUR SERVER POTATO AND CHEESE .................................................................6.95 PASTA SALAD..................................................................9.95 RAINBOW ROTINI, TOMATO, ROASTED RED MEAT COMBO ..................................................................................7.95 PEPPER, PEPPERONI, CHEDDAR AND VINAIGRETTE THE WORKS (ONE OF EACH) ...................................................9.95 -

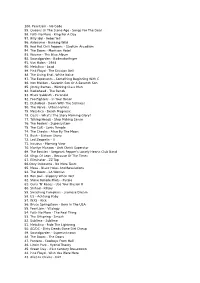

100. Pearl Jam - No Code 99

100. Pearl Jam - No Code 99. Queens Of The Stone Age - Songs For The Deaf 98. Faith No More - King For A Day 97. Billy Idol - Rebel Yell 96. Airbourne - Running Wild 95. Red Hot Chili Peppers - Stadium Arcadium 94. The Doors - Morrison Hotel 93. Weezer - The Blue Album 92. Soundgarden - Badmotorfinger 91. Van Halen - 1984 90. Metallica - Load 89. Pink Floyd - The Division Bell 88. The Living End - White Noise 87. The Exponents - Something Beginning With C 86. Iron Maiden - Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son 85. Jimmy Barnes - Working Class Man 84. Radiohead - The Bends 83. Black Sabbath - Paranoid 82. Foo Fighters - In Your Honor 81. Disturbed - Down With The Sickness 80. The Verve - Urban Hymns 79. Metallica - Death Magnetic 78. Oasis - What's The Story Morning Glory? 77. Talking Heads - Stop Making Sense 76. The Feelers - Supersystem 75. The Cult - Sonic Temple 74. The Checks - Alice By The Moon 73. Bush - Sixteen Stone 72. Led Zeppelin - II 71. Incubus - Morning View 70. Marilyn Manson - Anti Christ Superstar 69. The Beatles - Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band 68. Kings Of Leon - Because Of The Times 67. Eliminator - ZZ Top 66.Ozzy Osbourne - No More Tears 65. Muse - Black Holes And Revelations 64. The Doors - LA Woman 63. Bon Jovi - Slippery When Wet 62. Stone Temple Pilots - Purple 61. Guns 'N' Roses - Use Your Illusion II 60. Shihad - Killjoy 59. Smashing Pumpkins - Siamese Dream 58. U2 - Achtung Baby 57. INXS - Kick 56. Bruce Springsteen - Born In The USA 55. Pearl Jam - Vitalogy 54. Faith No More - The Real Thing 53. -

A Year in the Life of Bottle the Curmudgeon What You Are About to Read Is the Book of the Blog of the Facebook Project I Started When My Dad Died in 2019

A Year in the Life of Bottle the Curmudgeon What you are about to read is the book of the blog of the Facebook project I started when my dad died in 2019. It also happens to be many more things: a diary, a commentary on contemporaneous events, a series of stories, lectures, and diatribes on politics, religion, art, business, philosophy, and pop culture, all in the mostly daily publishing of 365 essays, ostensibly about an album, but really just what spewed from my brain while listening to an album. I finished the last essay on June 19, 2020 and began putting it into book from. The hyperlinked but typo rich version of these essays is available at: https://albumsforeternity.blogspot.com/ Thank you for reading, I hope you find it enjoyable, possibly even entertaining. bottleofbeef.com exists, why not give it a visit? Have an album you want me to review? Want to give feedback or converse about something? Send your own wordy words to [email protected] , and I will most likely reply. Unless you’re being a jerk. © Bottle of Beef 2020, all rights reserved. Welcome to my record collection. This is a book about my love of listening to albums. It started off as a nightly perusal of my dad's record collection (which sadly became mine) on my personal Facebook page. Over the ensuing months it became quite an enjoyable process of simply ranting about what I think is a real art form, the album. It exists in three forms: nightly posts on Facebook, a chronologically maintained blog that is still ongoing (though less frequent), and now this book. -

Vinyles Cassettes Minidiscs Cd

Ten Club Albums Singles VINYLES - Last Soldier (live) USA 2001 - Ten, Yellow Digipack 1 CD, UK - Love Boat Captain (3 titres) 1 CD, digipack Albums - Don't Believe In Christmas (live) USA 2002 - Ten 1 CD, Europe - Love Boat Captain (3 titres + 1 vidéo) 1 CD, digipack - Ten USA 1991 - Reach Down (live) USA 2003 - Ten 1 CD, Chine - Man of The Hour 1 CD, digipack - Ten Corée 1991 - Someday at Christmas USA 2004 - Ten ("The Vinyle Classics) 1 CD - Ten “Basketball picture-disc“ UK 1991 - Little Sister USA 2005 - Ten Legacy Edition 2 CD, Europe Promo - Vs USA 1993 - Love Rein o’er Me USA 2006 - Ten Deluxe Edition 2 CD, Europe - Why Go (Cultivate the tour) 1 CD - Vs Corée 1993 - Santa God USA 2007 - Ten remix (Super Deluxe Ed.) 1 CD, USA - Jeremy 1 CD - Vitalogy USA 1994 - Ten redux (Super Deluxe Ed.) 1 CD, USA - Spin The Black Circle 1 CD - No Code USA 1996 - Vs 1 CD - Immortality 1 CD - Yield USA 1998 - Vs 1 CD, USA - Of He Goes 1 CD - Live in Two Legs USA 1998 - Vs 1 CD, USA eco-pack - Given To Fly 1 CD - Binaural USA 2000 - Vs ("The Vinyle Classics) 1 CD CASSETTES - Given To Fly 1 CD - Riot Act USA 2002 - Vitalogy 1 CD, USA - Elderly Woman (live) 1 CD - Lost Dogs USA 2003 Promo - Vitalogy 1 CD, Europe - Live at Benaroya Hall USA 2004, numéroté - No Code 1 CD, USA - Do The Evolution 1 CD - Mother Love Bone - Shine promo USA 1989 - Rearviewmirror (Greatest Hits 91-03) USA 2004 - No Code 1 CD, Europe - Wishlist 1 CD - Alive USA 1991 - Pearl Jam USA 2006 - Yield 1 CD, USA - Even Flow (live) 1 CD - Into The Wild (+ 7”) USA 2008 - Yield 1 CD, -

Pearl Jam's Ten and the Road to Authenticity Introduction

‘I know someday you'll have a beautiful life': Pearl Jam's Ten and the road to authenticity Introduction Pearl Jam’s debut album is a special and important record in the context of both the alternative music grunge phenomenon of the 1990s and the band’s own growth as important rock musicians and artists in the subsequent twenty years. Indeed for many, Pearl Jam’s debut album, together with Nirvana’s Nevermind, is synonymous with the word grunge itself. The album is a seminal work that marked the mainstream breakthrough of guitarist Stone Gossard and bassist Jeff Ament, the founding members of grunge pioneers Green River and so has an important place in the genealogy of Seattle rock. It remains a commercial and critical success, selling nearly ten million copies, and being certified platinum thirteen times. It regularly features in ‘best of’ lists in the music press and popular journalism1. However, the commercial success of Pearl Jam and other bands from the region such as Nirvana, Soundgarden and Alice in Chains, raised questions about the authenticity of grunge as a musical style since it had initially presented itself as an underground and unreservedly alternative movement that shunned mainstream acceptance. Furthermore, the album’s highly polished style and intricate production did not sit comfortably with critics who claimed it was not faithful to a simpler, pared back ‘grunge sound’. The success and all of its associated trappings pushed the band into a position where they recognised the album as an emblem of inauthenticity. It was this very inauthenticity that later Pearl Jam albums and the band’s actions rallied against in subsequent years. -

Global Product Classification (GPC) - Development & Implementation Guide

Global Product Classification (GPC) - Development & Implementation Guide Global Product Classification (GPC) Development & Implementation Guide Issue 3, Oct-2012 Issue 3, Oct-2012 All contents copyright © GS1 Page 1 of 41 Global Product Classification (GPC) - Development & Implementation Guide Document Summary Document Item Current Value Document Title Global Product Classification (GPC) - Development & Implementation Guide Date Last Modified Oct-2012 Document Issue Issue 3 Document Status Approved Document Description This document will provide a reference for GPC principals, rules, development, implementation, and publication. It also defines the process of how GPC is integrated and implemented within GDSN. Contributors (Current) Name Organization GPC SMG GS1 Doug Bailey USDA Jean-Christophe Gilbert GS1 France Bruce Hawkins GS1 Global Office Mike Mowad GS1 Global Office Art Smith GS1 Canada Log of Changes in Issue 3 Issue No. Date of Change Changed By Summary of Change 1 Mar-2011 Mike Mowad Initial Version 2 Jan-2012 Mike Mowad Corrected Figure 2-3 (GPC Brick Attributes) Made process updates to section 5.6.1.3, 3 Oct-2012 Mike Mowad section 5.6.2.4, Figure 5-2, and Figure 6-1. Disclaimer WHILST EVERY EFFORT HAS BEEN MADE TO ENSURE THAT THE GUIDELINES TO USE THE GS1 STANDARDS CONTAINED IN THE DOCUMENT ARE CORRECT, GS1 AND ANY OTHER PARTY INVOLVED IN THE CREATION OF THE DOCUMENT HEREBY STATE THAT THE DOCUMENT IS PROVIDED WITHOUT WARRANTY, EITHER EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, REGARDING ANY MATTER, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO THE OF ACCURACY, MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, AND HEREBY DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL LIABILITY, DIRECT OR INDIRECT, FOR ANY DAMAGES OR LOSS RELATING TO OR RESULTING FROM THE USE OF THE DOCUMENT.