Pearl Jam's Ten and the Road to Authenticity Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R4C: a Benchmark for Evaluating RC Systems to Get the Right Answer for the Right Reason

R4C: A Benchmark for Evaluating RC Systems to Get the Right Answer for the Right Reason Naoya Inoue1;2 Pontus Stenetorp2;3 Kentaro Inui1;2 1Tohoku University 2RIKEN 3University College London fnaoya-i, [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Question What was the former band of the member of Mother Recent studies have revealed that reading com- Love Bone who died just before the release of “Apple”? prehension (RC) systems learn to exploit an- Articles notation artifacts and other biases in current Title: Return to Olympus [1] Return to Olympus is the datasets. This prevents the community from only album by the alternative rock band Malfunkshun. reliably measuring the progress of RC systems. [2] It was released after the band had broken up and 4 after lead singer Andrew Wood (later of Mother Love To address this issue, we introduce R C, a Input Bone) had died... [3] Stone Gossard had compiled… new task for evaluating RC systems’ internal Title: Mother Love Bone [4] Mother Love Bone was 4 reasoning. R C requires giving not only an- an American rock band that… [5] The band was active swers but also derivations: explanations that from… [6] Frontman Andrew Wood’s personality and justify predicted answers. We present a reli- compositions helped to catapult the group to... [7] Wood died only days before the scheduled release able, crowdsourced framework for scalably an- of the band’s debut album, “Apple”, thus ending the… notating RC datasets with derivations. We cre- ate and publicly release the R4C dataset, the Explanation Answer first, quality-assured dataset consisting of 4.6k Supporting facts (SFs): Malfunkshun questions, each of which is annotated with 3 [1], [2], [4], [6], [7] reference derivations (i.e. -

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green

AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long Adele Rolling in the Deep Al Green Let's Stay Together Alabama Dixieland Delight Alan Jackson It's Five O'Clock Somewhere Alex Claire Too Close Alice in Chains No Excuses America Lonely People Sister Golden Hair American Authors The Best Day of My Life Avicii Hey Brother Bad Company Feel Like Making Love Can't Get Enough of Your Love Bastille Pompeii Ben Harper Steal My Kisses Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Lean on Me Billy Joel You May Be Right Don't Ask Me Why Just the Way You Are Only the Good Die Young Still Rock and Roll to Me Captain Jack Blake Shelton Boys 'Round Here God Gave Me You Bob Dylan Tangled Up in Blue The Man in Me To Make You Feel My Love You Belong to Me Knocking on Heaven's Door Don't Think Twice Bob Marley and the Wailers One Love Three Little Birds Bob Seger Old Time Rock & Roll Night Moves Turn the Page Bobby Darin Beyond the Sea Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Living on a Prayer You Give Love a Bad Name Brad Paisley She's Everything Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruno Mars Locked Out of Heaven Marry You Treasure Bryan Adams Summer of '69 Cat Stevens Wild World If You Want to Sing Out CCR Bad Moon Rising Down on the Corner Have You Ever Seen the Rain Looking Out My Backdoor Midnight Special Cee Lo Green Forget You Charlie Pride Kiss an Angel Good Morning Cheap Trick I Want You to Want Me Christina Perri A Thousand Years Counting Crows Mr. -

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

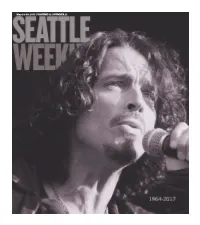

VOLUME 42 | NUMBER 21 Hen Chris Cornell Entered He Shrugged

May 24-30, 2017 | VOLUME 42 | NUMBER 21 hen Chris Cornell entered He shrugged. He spoke in short bursts of at a room, the air seemed to syllables. Soundgarden was split at the time, hum with his presence. All and he showed no interest in getting the eyes darted to him, then band back together. He showed little interest danced over his mop of in many of my questions. Until I noted he curls and lanky frame. He appeared to carry had a pattern of daring creative expression himself carelessly, but there was calculation outside of Soundgarden: Audioslave’s softer in his approach—the high, loose black side; bluesy solo eorts; the guitar-eschew- boots, tight jeans, and impeccable facial hair ing Scream with beatmaker Timbaland. his standard uniform. He was a rock star. At this, Cornell’s eyes sharpened. He He knew it. He knew you knew it. And that sprung forward and became fully engaged. didn’t make him any less likable. When he He got up and brought me an unsolicited left the stage—and, in my case, his Four bottled water, then paced a bit, talking all Seasons suite following a 2009 interview— the while. About needing to stay unpre- that hum leisurely faded, like dazzling dictable. About always trying new things. sunspots in the eyes. He told me that he wrote many songs “in at presence helped Cornell reach the character,” outside of himself. He said, “I’m pinnacle of popular music as front man for not trying to nd my musical identity, be- Soundgarden. -

La Fugazi Live Series Sylvain David

Document generated on 10/01/2021 9:37 p.m. Sens public « Archive-it-yourself » La Fugazi Live Series Sylvain David (Re)constituer l’archive Article abstract 2016 Fugazi, one of the most respected bands of the American independent music scene, recently posted almost all of its live performances online, releasing over URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1044387ar 800 recordings made between 1987 and 2003. Such a project is atypical both by DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1044387ar its size, rock groups being usually content to produce one or two live albums during the scope of their career, and by its perspective, Dischord Records, an See table of contents independent label, thus undertaking curatorial activities usually supported by official cultural institutions such as museums, libraries and universities. This approach will be considered here both in terms of documentation, the infinite variations of the concerts contrasting with the arrested versions of the studio Publisher(s) albums, and of the musical canon, Fugazi obviously wishing, by the Département des littératures de langue française constitution of this digital archive, to contribute to a parallel rock history. ISSN 2104-3272 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article David, S. (2016). « Archive-it-yourself » : la Fugazi Live Series. Sens public. https://doi.org/10.7202/1044387ar Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) Sens-Public, 2016 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. -

“Alive” Pearl Jam Ten (1991) Stone Gossard, Jeff Ament, Eddie Vedder, Mike Mccready, Dave Krusen

JAN/FEB 2010 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM BEHIND THE CLASSICS Lance Mercer “Alive” Pearl Jam Ten (1991) Stone Gossard, Jeff Ament, Eddie Vedder, Mike McCready, Dave Krusen ON A SUMMER DAY IN SAN DIEGO IN 1991, EDDIE I’m still alive.” “All he knows is ‘I’m still alive’—those three words, that’s Vedder paddled his surfboard out toward the horizon of the Pacifi c totally out of burden,” he said. “I’m the lover that’s still alive.” Thus Ocean and let his mind wander. Through a mutual friend, he had the instrumental that guitarist Stone Gossard had dubbed “Dollar just received a three-track instrumental demo from a band looking Short” was renamed “Alive.” for a lead singer and lyricist. As he rode the California waves, he Vedder’s tale only grew darker over the next two songs. In began imagining lyrics for the three songs—and a tragic melodrama “Once,” the son’s confusion and anger leads him to become a serial that would bind them together as a coherent story. killer. He is captured, and in “Footsteps” he laments his fate while The tale Vedder invented begins like this: A young man’s mother awaiting execution. Once the lyrics were completed, Vedder dubbed informs him that the man he believes to be his father is in fact his himself singing over the instrumentals and hastily mailed them to stepfather, and that his real father is dead. This much, at least, is Seattle. “The music just felt really open to me,” Vedder recalled in drawn from Vedder’s own autobiography. -

Emo Teens and the Rising Suicide Rate in SA

Emo teens and the rising suicide rate in SA An alarming number of South African teens not only harm themselves, they are actively contemplating suicide. One group that's especially at risk is the subgroup known as Emos. "I could have stopped it… she was my best friend. I never thought it was this bad. You know… we all have problems. I thought it was just another bad day." These are the words of a young grade-10 learner who recently lost her best friend due to suicide. Suicide is the cause for almost one in 10 teenage deaths in South Africa and there is growing evidence that social media sites are in part to blame for this ever increasing figure. One group of teen 'outsiders', known as Emos, and who primarily use the Internet to connect with like-minded others, seems to be particularly at risk of suicide and suicidal behaviour such as self -harming. According to a 2012 Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) study that analysed the content of “Emo” teenage groups on Facebook they found there is indeed a connection between teen use of social media and the 'glamourisation' of suicidal behavior. Who are these emo kids? The Emo phenomenon (emo is an abbreviation for emotional) began in the U.S. in the 1980s and spread across the world, from the US to Europe, Russia, the Middle East and South Africa. It is a largely teenage trend and the members are characterised by depression and self harming - self-harm includes attempted suicide and what's known as self harming or non-suicidal self- injury (NSSI), along with the glamourisation of suicide. -

Riot Act Free

FREE RIOT ACT PDF Zoe Sharp | 316 pages | 29 Jan 2013 | Murderati Ink (ZACE Ltd) | 9781909344013 | English | Kendal, United Kingdom 'Read the riot act' - meaning and origin. Featured on Intense Socialization. This duo plays a completely different Riot Act list of songs that covers four decades of rock and Riot Act, ranging from Sublime and Bob Marley, to Paul Simon and Peter Gabriel. The current line-up consists of four veteran musicians. View Profile. Check out our original music. You can easily purchase our music through our online store. Riot Act the musical mayhem coming soon to a venue near you! Riot Riot Act will be heating up the stage at RiverFire Book a room and take a road trip with us. The Rebooted line-up consists of four veteran musicians: […]. The current Riot Act consists of four veteran musicians: Johnny […]. Site Designed and maintained by accomtec. Follow us:. Upcoming Shows. Music Video Distant Early Warning. Whatch now. Welcome to RiotAct. Read more. Riot Act The current line-up consists of four veteran musicians. Chris Michaud bass guitar. Riot Act Guitar Vocals. Bass Guitar, Vocals with Riot Act! Lead Guitar Rhythm Guitar Vocals. Drums Percussion. Drums, Vocals with Riot Act! All Artists Music. Original Music Check out our original music. Intense Socialization Request Now Clear. Latest News Experience the musical mayhem coming soon to a venue near you! Riot Act (album) - Wikipedia Following a full-scale tour in support of their previous album, BinauralPearl Jam took a year-long Riot Act. The band reconvened in the beginning of and commenced work on a new album. -

Pearl Jam & Eddie Vedder

PEARL JAM & EDDIE VEDDER: NONE TOO FRAGILE : REVISED AND UPDATED PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin Clarke | 192 pages | 31 Dec 2020 | Plexus Publishing Ltd | 9780859655590 | English | London, United Kingdom Pearl Jam & Eddie Vedder: None Too Fragile : Revised and Updated PDF Book Ones ability to decipher the written word as it is manipulated throughout a particular song or poem gives much insight into ones thoughts or the thoughts into that of the author. As somebody wrote before, it reflects the years of making music.. Obviously, they were thinking about releasing the entire VFC show -- which would seem like they were considering donating the proceeds to VFC - this is conjecture, we don't know this for certain. Previous Story. We have ratings, but no written reviews for this, yet. The overall death rate is 1. Anonymous September 23, at PM. Young will be showing up on stage at the second Maui show tomorrow the 21st. Martyn marvelled at the breadth of creative talent the project has attracted, with submissions ranging from doodles, sketches, digital drawings, paintings, pastels, photos and even one musical composition. Email This BlogThis! Eddie on Letterman: Mystery Solved! First Edition,First Printing Over the 20 years of President Vladimir Putin's rule, the Kremlin has struggled to reconcile both realities. Over three decades after Friends First Recent Popular. More news as we have it! The overall death rate is 2. She is just as tempted by the Sirens as he. Brendan O'Brien Pearl Jam. ET on Friday, Jan. Over the past seven days, there have been a total of one new cases. -

„Lightning Bolt“ Nachfolger Von „Backspacer“ Pearl Jam Im Oktober Mit Neuem Studioalbum

Ob ihr neues Album "Lightning Bolt" ähnlich frisch klingt wie "Backspacer" vor vier Jahren? Pearl Jam stehen vor der Veröffentlichung ihres zehnten Albums. „Lightning Bolt“ Nachfolger von „Backspacer“ Pearl Jam im Oktober mit neuem Studioalbum 12. Juli 2013, Von: Redaktion, Foto(s): Steve Gullick Als die US-Grunge-Rocker Pearl Jam vor vier Jahren ihr Album „Backspacer“ auf den Markt brachten, glaubten einige, die Band hätte eine besonders intensive musikalische Frischzellenkur genossen: Griffiges Songwriting, modernes, leicht extravagantes Coverartwork und ein knackig-frischer Sound zeichneten das von Brendan ´O Brien produzierte Album aus. Der Produzent ist geblieben, die Songs sind neu: Im Oktober präsentieren Pearl Jam ihr neuestes Studiowerk. Es kommt vor, dass Pearl Jam vor allem mit der Seattle-Grunge-Ära der frühen Neunziger in Verbindung gebracht, als die Band um Sänger und Frontmann Eddie Vedder mit Bands wie Nirvana die Speerspitze des Genres bildete. Alben wie das 1991 erschiene „Ten“ oder der 1993er-Longplayer „Vs.“ zählen zu den besonders populären Platten der Band. Wer Pearl Jam in jüngerer Vergangenheit ein wenig aus den Augen verloren hat, der mag sich wundern, wie frisch, spielfreudig und gewissermaßen auch jung die Band auf dem im September 2009 veröffentlichten und vielbeachteten Album „Backspacer“ herüberkommt, das mit rund 32 Minuten Spielzeit recht kurz ausgefallen ist, dafür aber nach Ansicht vieler um so packender und kurzweiliger klingt. Für den 11.Oktober, also gut vier Jahre nach „Backspacer“ kündigen Pearl Jam die Veröffentlichung ihres neue Studioalbums „Lightning Bolt“, die mittlerweile zehnte Platte der Band, an. Versprochen werden im Vorfeld „klassische Gitarrensounds“ und „mitreißendes Songwriting“ (Medieninfo). Auch 12. -

The Sociology of Youth Subcultures

Peace Review 16:4, December (2004), 409-4J 4 The Sociology of Youth Subcultures Alan O'Connor The main theme in the sociology of youth subcultures is the reladon between social class and everyday experience. There are many ways of thinking about social class. In the work of the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu the main factors involved are parents' occupation and level of education. These have signilicant effects on the life chances of their children. Social class is not a social group: the idea is not that working class kids or middle class kids only hang out together. There may be some of this in any school or town. Social class is a structure. It is shown to exist by sociological research and many people may only be partly aware of these structures or may lack the vocabulary to talk about them. It is often the case that people blame themselves—their bad school grades or dead-end job—for what are, at least in part, the effects of a system of social class that has had significant effects on their lives. The main point of Bourdieu's research is to show that many kids never had a fair chance from the beginning. n spite of talk about "globalizadon" there are significant differences between Idifferent sociedes. Social class works differently in France, Mexico and the U.S. For example, the educadon system is different in each country. In studying issues of youth culture, it is important to take these differences into account. The system of social class in each country is always experienced in complex ways.