Iraq Synthesis Paper Understanding the Drivers of Conflict in Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Resurgence of Asa'ib Ahl Al-Haq

December 2012 Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ Photo Credit: Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq protest in Kadhimiya, Baghdad, September 2012. Photo posted on Twitter by Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2012 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2012 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 Washington, DC 20036. http://www.understandingwar.org Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Sam Wyer is a Research Analyst at the Institute for the Study of War, where he focuses on Iraqi security and political matters. Prior to joining ISW, he worked as a Research Intern at AEI’s Critical Threats Project where he researched Iraqi Shi’a militia groups and Iranian proxy strategy. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science from Middlebury College in Vermont and studied Arabic at Middlebury’s school in Alexandria, Egypt. ABOUT THE INSTITUTE The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) is a non-partisan, non-profit, public policy research organization. ISW advances an informed understanding of military affairs through reliable research, trusted analysis, and innovative education. ISW is committed to improving the nation’s ability to execute military operations and respond to emerging threats in order to achieve U.S. -

Blood and Ballots the Effect of Violence on Voting Behavior in Iraq

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Göteborgs universitets publikationer - e-publicering och e-arkiv DEPTARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE BLOOD AND BALLOTS THE EFFECT OF VIOLENCE ON VOTING BEHAVIOR IN IRAQ Amer Naji Master’s Thesis: 30 higher education credits Programme: Master’s Programme in Political Science Date: Spring 2016 Supervisor: Andreas Bågenholm Words: 14391 Abstract Iraq is a very diverse country, both ethnically and religiously, and its political system is characterized by severe polarization along ethno-sectarian loyalties. Since 2003, the country suffered from persistent indiscriminating terrorism and communal violence. Previous literature has rarely connected violence to election in Iraq. I argue that violence is responsible for the increases of within group cohesion and distrust towards people from other groups, resulting in politicization of the ethno-sectarian identities i.e. making ethno-sectarian parties more preferable than secular ones. This study is based on a unique dataset that includes civil terror casualties one year before election, the results of the four general elections of January 30th, and December 15th, 2005, March 7th, 2010 and April 30th, 2014 as well as demographic and socioeconomic indicators on the provincial level. Employing panel data analysis, the results show that Iraqi people are sensitive to violence and it has a very negative effect on vote share of secular parties. Also, terrorism has different degrees of effect on different groups. The Sunni Arabs are the most sensitive group. They change their electoral preference in response to the level of violence. 2 Acknowledgement I would first like to thank my advisor Dr. -

Ba'ath Propaganda During the Iran-Iraq War Jennie Matuschak [email protected]

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2019 Nationalism and Multi-Dimensional Identities: Ba'ath Propaganda During the Iran-Iraq War Jennie Matuschak [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Matuschak, Jennie, "Nationalism and Multi-Dimensional Identities: Ba'ath Propaganda During the Iran-Iraq War" (2019). Honors Theses. 486. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/486 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. iii Acknowledgments My first thanks is to my advisor, Mehmet Döşemeci. Without taking your class my freshman year, I probably would not have become a history major, which has changed my outlook on the world. Time will tell whether this is good or bad, but for now I am appreciative of your guidance. Also, thank you to my second advisor, Beeta Baghoolizadeh, who dealt with draft after draft and provided my thesis with the critiques it needed to stand strongly on its own. Thank you to my friends for your support and loyalty over the past four years, which have pushed me to become the best version of myself. Most importantly, I value the distractions when I needed a break from hanging out with Saddam. Special shout-out to Andrew Raisner for painstakingly reading and editing everything I’ve written, starting from my proposal all the way to the final piece. -

Reimagining US Strategy in the Middle East

REIMAGININGR I A I I G U.S.S STRATEGYT A E Y IIN THET E MMIDDLED L EEASTS Sustainable Partnerships, Strategic Investments Dalia Dassa Kaye, Linda Robinson, Jeffrey Martini, Nathan Vest, Ashley L. Rhoades C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RRA958-1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0662-0 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. 2021 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover composite design: Jessica Arana Image: wael alreweie / Getty Images Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface U.S. -

Towards a Policy Framework for Iraq's Petroleum Industry and An

Towards a Policy Framework for Iraq’s Petroleum Industry and an Integrated Federal Energy Strategy Submitted by Luay Jawad al-Khatteeb To the University of Exeter As a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Middle East Politics In January 2017 The thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature ......................................................... i Abstract: The “Policy Framework for Iraq’s Petroleum Industry” is a logical structure that establishes the rules to guide decisions and manage processes to achieve economically efficient outcomes within the energy sector. It divides policy applications between regulatory and regulated practices, and defines the governance of the public sector across the petroleum industry and relevant energy portfolios. In many “Rentier States” where countries depend on a single source of income such as oil revenues, overlapping powers of authority within the public sector between policy makers and operators has led to significant conflicts of interest that have resulted in the mismanagement of resources and revenues, corruption, failed strategies and the ultimate failure of the system. Some countries have succeeded in identifying areas for progressive reform, whilst others failed due to various reasons discussed in this thesis. Iraq fits into the category of a country that has failed to implement reform and has become a classic case of a rentier state. -

Vichy on the Tigris

susan watkins Editorial VICHY ON THE TIGRIS His Majesty’s Government and I are in the same boat and must sink or swim together . if you wish me and your policy to succeed, it is folly to damn me permanently in the public eye by making me an obvious puppet. King Faisal I to the British High Commissioner, Mesopotamia, 17 August 1921.1 arely has a passage of powers been so furtive. The ceremony—held two days ahead of schedule, deep within Baghdad’s fortified Green Zone—lasted just ten min- utes, with thirty us and Iraqi officials present. Outside the Rcement stockade, the military realities remain the same: an Occupation force of 160,000 us-led troops, an additional army of commercial secu- rity guards, and jumpy local police units. Before departing, the Coalition Provisional Authority set in place a parallel government structure of Commissioners and Inspectors-General (still referring to themselves as ‘coalition officials’ a week after the supposed dissolution of that body) who, elections notwithstanding, will control Iraq’s chief ministries for the next five years.2 The largest us embassy in the world will dominate Baghdad, with regional ‘hubs’ planned in Mosul, Kirkuk, Hilla and Basra. Most of the $3.2 billion that has been contracted so far is going on the construction of foreign military bases.3 The un has resolved that the country’s oil revenues will continue to be deposited in the us-dominated Development Fund for Iraq, again for the next five years. The newly installed Allawi government will have no authority to reallocate contracts signed by the cpa, largely with foreign companies who will remain above the law of the land. -

Irrigation of World Agricultural Lands: Evolution Through the Millennia

water Review Irrigation of World Agricultural Lands: Evolution through the Millennia Andreas N. Angelakιs 1 , Daniele Zaccaria 2,*, Jens Krasilnikoff 3, Miquel Salgot 4, Mohamed Bazza 5, Paolo Roccaro 6, Blanca Jimenez 7, Arun Kumar 8 , Wang Yinghua 9, Alper Baba 10, Jessica Anne Harrison 11, Andrea Garduno-Jimenez 12 and Elias Fereres 13 1 HAO-Demeter, Agricultural Research Institution of Crete, 71300 Iraklion and Union of Hellenic Water Supply and Sewerage Operators, 41222 Larissa, Greece; [email protected] 2 Department of Land, Air, and Water Resources, University of California, California, CA 95064, USA 3 School of Culture and Society, Department of History and Classical Studies, Aarhus University, 8000 Aarhus, Denmark; [email protected] 4 Soil Science Unit, Facultat de Farmàcia, Universitat de Barcelona, 08007 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 5 Formerly at Land and Water Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations-FAO, 00153 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 6 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Catania, 2 I-95131 Catania, Italy; [email protected] 7 The Comisión Nacional del Agua in Mexico City, Del. Coyoacán, México 04340, Mexico; [email protected] 8 Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi 110016, India; [email protected] 9 Department of Water Conservancy History, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing 100048, China; [email protected] 10 Izmir Institute of Technology, Engineering Faculty, Department of Civil -

Steven Isaac “The Ba'th of Syria and Iraq”

Steven Isaac “The Ba‘th of Syria and Iraq” for The Encyclopedia of Protest and Revolution (forthcoming from Oxford University Press) Three main currents of socialist thought flowed through the Arab world during and after World War II: The Ba‘th party’s version, that of Nasser, and the options promulgated by the region’s various communist parties. None of these can really be considered apart from the others. The history of Arab communists is often a story of their rivalry and occasional cohabitation with other movements, so this article will focus first on the Ba‘th and then on Nasser while telling the story of all three. In addition, the Ba‘th were active in more places than just Syria and Iraq, although those countries saw their most signal successes (and concomitant disappointments). Michel Aflaq, a Sorbonne-educated, Syrian Christian, was one of the two primary founders of the Ba‘th (often transliterated as Baath or Ba‘ath) movement. His exposure to Marx came during his studies in France, and he associated for some time with the communists in Syria after his return there in 1932. He later declared his fascination with communism ended by 1936, but others cite him as still a confirmed party member until 1943. His co-founder, Salah al-Din al-Bitar, likewise went to France for his university education and returned to Syria to be a teacher. Frustrated by France’s inter-war policies, the nationalism of both men came to so influence their attitudes towards the West that even Western socialism became another form of imperialism. -

Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance

Order Code RL31339 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance Updated May 16, 2005 Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq: U.S. Regime Change Efforts and Post-Saddam Governance Summary Operation Iraqi Freedom accomplished a long-standing U.S. objective, the overthrow of Saddam Hussein, but replacing his regime with a stable, moderate, democratic political structure has been complicated by a persistent Sunni Arab-led insurgency. The Bush Administration asserts that establishing democracy in Iraq will catalyze the promotion of democracy throughout the Middle East. The desired outcome would also likely prevent Iraq from becoming a sanctuary for terrorists, a key recommendation of the 9/11 Commission report. The Bush Administration asserts that U.S. policy in Iraq is now showing substantial success, demonstrated by January 30, 2005 elections that chose a National Assembly, and progress in building Iraq’s various security forces. The Administration says it expects that the current transition roadmap — including votes on a permanent constitution by October 31, 2005 and for a permanent government by December 15, 2005 — are being implemented. Others believe the insurgency is widespread, as shown by its recent attacks, and that the Iraqi government could not stand on its own were U.S. and allied international forces to withdraw from Iraq. Some U.S. commanders and senior intelligence officials say that some Islamic militants have entered Iraq since Saddam Hussein fell, to fight what they see as a new “jihad” (Islamic war) against the United States. -

The Future of US-Iraq Relations

The Future of US-Iraq Relations Ellen Laipson The Future of US-Iraq Relations Ellen Laipson Copyright © 2010 The Henry L. Stimson Center ISBN: 978-0-9845211-0-4 Cover photos: USAID, US Army, US Department of Defense Book and cover design by Shawn Woodley An electronic version of this publication is available at: www.stimson.org/swa All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW, 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 Telephone: 202.223.5956 Fax: 202.238.9604 www.stimson.org Contents Preface .......................................................................................................................v Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................vi Introduction ............................................................................................................vii Iraq-US Relations in 2010: A Time of Transition ......................................................1 Security Relations Still Dominant .....................................................................2 The Civilian Surge ............................................................................................4 US Embassy Baghdad ................................................................................8 The Human Cost of the War: Refugees and Veterans ........................................9 Efforts to Help Returning -

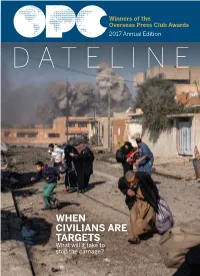

WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What Will It Take to Stop the Carnage?

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2017 Annual Edition DATELINE WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What will it take to stop the carnage? DATELINE 2017 1 President’s Letter / dEIdRE dEPkE here is a theme to our gathering tonight at the 78th entries, narrowing them to our 22 winners. Our judging process was annual Overseas Press Club Gala, and it’s not an easy one. ably led by Scott Kraft of the Los Our work as journalists across the globe is under Angeles Times. Sarah Lubman headed our din- unprecedented and frightening attack. Since the conflict in ner committee, setting new records TSyria began in 2011, 107 journalists there have been killed, according the for participation. She was support- Committee to Protect Journalists. That’s more members of the press corps ed by Bill Holstein, past president of the OPC and current head of to die than were lost during 20 years of war in Vietnam. In the past year, the OPC Foundation’s board, and our colleagues also have been fatally targeted in Iraq, Yemen and Ukraine. assisted by her Brunswick colleague Beatriz Garcia. Since 2013, the Islamic State has captured or killed 11 journalists. Almost This outstanding issue of Date- 300 reporters, editors and photographers are being illegally detained by line was edited by Michael Serrill, a past president of the OPC. Vera governments around the world, with at least 81 journalists imprisoned Naughton is the designer (she also in Turkey alone. And at home, we have been labeled the “enemy of the recently updated the OPC logo). -

Egyptian and Greek Water Cultures and Hydro-Technologies in Ancient Times

sustainability Review Egyptian and Greek Water Cultures and Hydro-Technologies in Ancient Times Abdelkader T. Ahmed 1,2,* , Fatma El Gohary 3, Vasileios A. Tzanakakis 4 and Andreas N. Angelakis 5,6 1 Civil Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Aswan University, Aswan 81542, Egypt 2 Civil Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Islamic University, Madinah 42351, Saudi Arabia 3 Water Pollution Research Department, National Research Centre, Cairo 12622, Egypt; [email protected] 4 Department of Agriculture, School of Agricultural Science, Hellenic Mediterranean University, Iraklion, 71410 Crete, Greece; [email protected] 5 HAO-Demeter, Agricultural Research Institution of Crete, 71300 Iraklion, Greece; [email protected] 6 Union of Water Supply and Sewerage Enterprises, 41222 Larissa, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 October 2020; Accepted: 19 November 2020; Published: 23 November 2020 Abstract: Egyptian and Greek ancient civilizations prevailed in eastern Mediterranean since prehistoric times. The Egyptian civilization is thought to have been begun in about 3150 BC until 31 BC. For the ancient Greek civilization, it started in the period of Minoan (ca. 3200 BC) up to the ending of the Hellenistic era. There are various parallels and dissimilarities between both civilizations. They co-existed during a certain timeframe (from ca. 2000 to ca. 146 BC); however, they were in two different geographic areas. Both civilizations were massive traders, subsequently, they deeply influenced the regional civilizations which have developed in that region. Various scientific and technological principles were established by both civilizations through their long histories. Water management was one of these major technologies. Accordingly, they have significantly influenced the ancient world’s hydro-technologies.