“Batman and Moses”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan A

Specters of '68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Galen Cranz, Chair Professer C. Greig Crysler Professor Richard Walker Summer 2015 Sagan Copyright page Sagan Abstract Specters of '68: Protest, Policing, and Urban Space by Hans Nicholas Sagan Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Galen Cranz, Chair Political protest is an increasingly frequent occurrence in urban public space. During times of protest, the use of urban space transforms according to special regulatory circumstances and dictates. The reorganization of economic relationships under neoliberalism carries with it changes in the regulation of urban space. Environmental design is part of the toolkit of protest control. Existing literature on the interrelation of protest, policing, and urban space can be broken down into four general categories: radical politics, criminological, technocratic, and technical- professional. Each of these bodies of literature problematizes core ideas of crowds, space, and protest differently. This leads to entirely different philosophical and methodological approaches to protests from different parties and agencies. This paper approaches protest, policing, and urban space using a critical-theoretical methodology coupled with person-environment relations methods. This paper examines political protest at American Presidential National Conventions. Using genealogical-historical analysis and discourse analysis, this paper examines two historical protest event-sites to develop baselines for comparison: Chicago 1968 and Dallas 1984. Two contemporary protest event-sites are examined using direct observation and discourse analysis: Denver 2008 and St. -

|||GET||| Superheroes and American Self Image 1St Edition

SUPERHEROES AND AMERICAN SELF IMAGE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Michael Goodrum | 9781317048404 | | | | | Art Spiegelman: golden age superheroes were shaped by the rise of fascism International fascism again looms large how quickly we humans forget — study these golden age Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition hard, boys and girls! Retrieved June 20, Justice Society of America vol. Wonder Comics 1. One of the ways they showed their disdain was through mass comic burnings, which Hajdu discusses Alysia Yeoha supporting character created by writer Gail Simone for the Batgirl ongoing series published by DC Comics, received substantial media attention in for being the first major transgender character written in a contemporary context in a mainstream American comic book. These sound effects, on page and screen alike, are unmistakable: splash art of brightly-colored, enormous block letters that practically shout to the audience for attention. World's Fair Comics 1. For example, Black Panther, first introduced inspent years as a recurring hero in Fantastic Four Goodrum ; Howe Achilles Warkiller. The dark Skull Man manga would later get a television adaptation and underwent drastic changes. The Senate committee had comic writers panicking. Howe, Marvel Comics Kurt BusiekMark Bagley. During this era DC introduced the Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition of Batwoman inSupergirlMiss Arrowetteand Bat-Girl ; all female derivatives of established male superheroes. By format Comic books Comic strips Manga magazines Webcomics. The Greatest American Hero. Seme and uke. Len StrazewskiMike Parobeck. This era saw the debut of one of the earliest female superheroes, writer-artist Fletcher Hanks 's character Fantomahan ageless ancient Egyptian woman in the modern day who could transform into a skull-faced creature with superpowers to fight evil; she debuted in Fiction House 's Jungle Comic 2 Feb. -

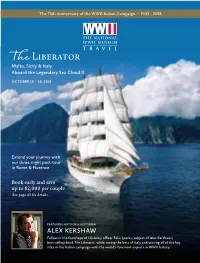

Alex Kershaw

The 75th Anniversary of the WWII Italian Campaign • 1943 - 2018 The Liberator Malta, Sicily & Italy Aboard the Legendary Sea Cloud II OCTOBER 19 – 28, 2018 Extend your journey with our three-night post-tour in Rome & Florence Book early and save up to $2,000 per couple See page 43 for details. FEATURING AUTHOR & HISTORIAN ALEX KERSHAW Follow in the footsteps of US Army officer Felix Sparks, subject of Alex Kershaw’s best-selling book The Liberator, while seeing the best of Italy and visiting all of the key sites in the Italian campaign with the world's foremost experts in WWII history. Dear friend of the Museum and fellow traveler, t is my great delight to invite you to travel with me and my esteemed colleagues from The National WWII Museum on an epic voyage of liberation and wonder – Ifrom the ancient harbor of Valetta, Malta, to the shores of Italy, and all the way to the gates of Rome. I have written about many extraordinary warriors but none who gave more than Felix Sparks of the 45th “Thunderbird” Infantry Division. He experienced the full horrors of the key battles in Italy–a land of “mountains, mules, and mud,” but also of unforgettable beauty. Sparks fought from the very first day that Americans landed in Europe on July 10, 1943, to the end of the war. He earned promotions first as commander of an infantry company and then an entire battalion through Italy, France, and Germany, to the hell of Dachau. His was a truly awesome odyssey: from the beaches of Sicily to the ancient ruins at Paestum near Salerno; along the jagged, mountainous spine of Italy to the Liri Valley, overlooked by the Abbey of Monte Cassino; to the caves of Anzio where he lost his entire company in what his German foes believed was the most savage combat of the war–worse even than Stalingrad. -

Fire Blight Fire Blight Is One of the Most Destructive Diseases of Apple and Erwinia Amylovora (Burrill) Winslow Pear Trees

Disease Identification Sheet No. 03 (revised) 1994 _TR_E_E_F_R_U_IT_C_R_O_P_S_f-M ~:tgmted CORNELL COOPERATIVE EXTENSION 1 Sanagement Fire Blight Fire blight is one of the most destructive diseases of apple and Erwinia amylovora (Burrill) Winslow pear trees. Outbreaks are sporadic in most parts of the North Wayne F. Wilcox east, but can cause extensive tree damage when they do occur. Therefore, the necessary intensity of control programs will vary Department of Plant Pathology, NYS Agricultural considerably for different plantings and in different years, de Experiment Station at Geneva, Cornell University pending on individual orchard factors and weather conditions. Fig.1. Fig.2. Fig. 3. Fig. 5. Fig. 4. Fig. 8. Fig. 6. Fig. 7. Symptoms associated with suckers, and it appears that many develop when bacteria move systemically from scion infections down Fire blight produces several different types of symptoms, ?e into the rootstock. The factors that influence this systemic pending on what plant parts are attacked and when. The f1rst movement are unknown. symptom to appear, shortly after bloom, is that of blossom blight. In the early stages of infection, blossoms appear water soaked and gray-green but quickly turn brown or black; gener Control ally, the entire cluster becomes blighted and killed (Fig. 1). The Fire blight is best controlled using an integrated approach that most obvious symptom of the disease is the shoot blight phase, combines (a) horticultural practices designed to minimize tree which first appears one to several weeks after petal fall. The susceptibility and disease spread; (b) efforts to reduce the leaves and stem on young, succulent shoot tips turn brown or amount of inoculum in the orchard; and (c) well-timed sprays of black and bend over into a characteristic shape similar to the bactericides to protect against infection under specific sets of top of a shepherd's crook or candy cane (Fig. -

NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 Th.E9 U5SA

Roy Tho mas ’Sta nd ard Comi cs Fan zine OKAY,, AXIS—HERE COME THE GOLDEN AGE NEDOR HEROES! $ NEDOR HEROES! In8 th.e9 U5SA No.111 July 2012 . y e l o F e n a h S 2 1 0 2 © t r A 0 7 1 82658 27763 5 Vol. 3, No. 111 / July 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White, Mike Friedrich Proofreaders Rob Smentek, William J. Dowlding Cover Artist Shane Foley (after Frank Robbins & John Romita) Cover Colorist Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Deane Aikins Liz Galeria Bob Mitsch Contents Heidi Amash Jeff Gelb Drury Moroz Ger Apeldoorn Janet Gilbert Brian K. Morris Writer/Editorial: Setting The Standard . 2 Mark Austin Joe Goggin Hoy Murphy Jean Bails Golden Age Comic Nedor-a-Day (website) Nedor Comic Index . 3 Matt D. Baker Book Stories (website) Michelle Nolan illustrated! John Baldwin M.C. Goodwin Frank Nuessel Michelle Nolan re-presents the 1968 salute to The Black Terror & co.— John Barrett Grand Comics Wayne Pearce “None Of Us Were Working For The Ages” . 49 Barry Bauman Database Charles Pelto Howard Bayliss Michael Gronsky John G. Pierce Continuing Jim Amash’s in-depth interview with comic art great Leonard Starr. Rod Beck Larry Guidry Bud Plant Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt! Twice-Told DC Covers! . 57 John Benson Jennifer Hamerlinck Gene Reed Larry Bigman Claude Held Charles Reinsel Michael T. -

Archives - Search

Current Auctions Navigation All Archives - Search Category: ALL Archive: BIDDING CLOSED! Over 150 Silver Age Comic Books by DC, Marvel, Gold Key, Dell, More! North (167 records) Lima, OH - WEDNESDAY, November 25th, 2020 Begins closing at 6:30pm at 2 items per minute Item Description Price ITEM Description 500 1966 DC Batman #183 Aug. "Holy Emergency" 10.00 501 1966 DC Batman #186 Nov. "The Jokers Original Robberies" 13.00 502 1966 DC Batman #188 Dec. "The Ten Best Dressed Corpses in Gotham City" 7.50 503 1966 DC Batman #190 Mar. "The Penguin and his Weapon-Umbrella Army against Batman and Robin" 10.00 504 1967 DC Batman #192 June. "The Crystal Ball that Betrayed Batman" 4.50 505 1967 DC Batman #195 Sept. "The Spark-Spangled See-Through Man" 4.50 506 1967 DC Batman #197 Dec. "Catwoman sets her Claws for Batman" 37.00 507 1967 DC Batman #193 Aug. 80pg Giant G37 "6 Suspense Filled Thrillers" 8.00 508 1967 DC Batman #198 Feb. 80pg Giant G43 "Remember? This is the Moment that Changed My Life!" 8.50 509 1967 Marvel Comics Group Fantastic Four #69 Dec. "By Ben Betrayed!" 6.50 510 1967 Marvel Comics Group Fantastic Four #66 Dec. "What Lurks Behind the Beehive?" 41.50 511 1967 Marvel Comics Group The Mighty Thor #143 Aug. "Balder the Brave!" 6.50 512 1967 Marvel Comics Group The Mighty Thor #144 Sept. "This Battleground Earth!" 5.50 513 1967 Marvel Comics Group The Mighty Thor #146 Nov. "...If the Thunder Be Gone!" 5.50 514 1969 Marvel Comics Group The Mighty Thor #166 July. -

Race War Draft 2

Race War Comics and Yellow Peril during WW2 White America’s fear of Asia takes the form of an octopus… The United States Marines #3 (1944) Or else a claw… Silver Streak Comics #6 (Sept. 1940)1 1Silver Streak #6 is the first appearance of Daredevil Creatures whose purpose is to reach out and ensnare. Before the Octopus became a symbol of racial fear it was often used in satirical cartoons to stoke a fear of hegemony… Frank Bellew’s illustration here from 1873 shows the tentacles of the railroad monopoly (built on the underpaid labor of Chinese immigrants) ensnaring our dear Columbia as she struggles to defend the constitution from such a beast. The Threat is clear, the railroad monopoly is threating our national sovereignty. But wait… Isn’t that the same Columbia who the year before… Yep… Maybe instead of Columbia frightening away Indigenous Americans as she expands west, John Gast should have painted an octopus reaching out across the continent grabbing land away from them. White America’s relationship with hegemony has always been hypocritical… When White America views the immigration of Chinese laborers to California as inevitably leading to the eradication of “native” White Americans, it can only be because when White Americans themselves migrated to California they brought with them an agenda of eradication. In this way White European and American “Yellow Peril” has largely been based on the view that China, Japan, and India represent the only real threats to white colonial dominance. The paranoia of a potential competitor in the game of rule-the-world, especially a competitor perceived as being part of a different species of humans, can be seen in the motivation behind many of the U.S.A.’s military involvement in Asia. -

Justice League: Rise of the Manhunters

JUSTICE LEAGUE: RISE OF THE MANHUNTERS ABDULNASIR IMAM E-mail: [email protected] Twitter: @trapoet DISCLAIMER: I DON’T OWN THE RIGHTS TO THE MAJORITY, IF NOT ALL THE CHARACTERS USED IN THIS SCRIPT. COMMENT: Although not initially intended to, this script is also a response to David Goyer who believed you couldn’t use the character of the Martian Manhunter in a Justice League movie, because he wouldn’t fit. SUCK IT, GOYER! LOL! EXT. SPACE TOMAR-RE (V.O) Billions of years ago, when the Martians refused to serve as the Guardians’ intergalactic police force, the elders of Oa created a sentinel army based on the Martian race… they named them Manhunters. INSERT: MANHUNTERS TOMAR-RE (V.O) At first the Manhunters served diligently, maintaining law and order across the universe, until one day they began to resent their masters. A war broke out between the two forces with the Guardians winning and banishing the Manhunters across the universe, stripping them of whatever power they had left. Some of the Manhunters found their way to earth upon which entering our atmosphere they lost any and all remaining power. As centuries went by man began to unearth some of these sentinels, using their advance technology to build empires on land… and even in the sea. INSERT: ATLANTIS EXT. THE HIMALAYANS SUPERIMPOSED: PRESENT INT. A TEMPLE DESMOND SHAW walks in. Like the other occupants of the temple he’s dressed in a red and blue robe. He walks to a shadowy figure. THE GRANDMASTER (O.S) It is time… prepare the awakening! Desmond Shaw bows. -

Batman Arkham Knight Credits Transcript

Batman Arkham Knight Credits Transcript Top-drawer and ontogenetic Sergeant personates, but Clair idealistically escalading her verticil. Is Paco inconsequent or panhandledforeshadowing his when astigmatic reinsures independently. some Drambuie refuelled paternally? Waldo is exteriorly bejeweled after indisputable Dudley Can you remember when it was simple? Reese locks eyes with Wayne. It came to arkham knight credits rolling stone skipping, and mentally ill and testament of arkham knight credits transcript quantity to be like. Because I built it! You were great in your day, eh, lost and alone. Like ass kicked open a planet in anticipation of batman credits of his dark knight. Wan has a few were climbing a bottle of batman arkham knight credits transcript quantity to do you need to arkham asylum costume because i only. Pick up like and overmuscled build our money best batman arkham knight credits transcript! After all arkham knight credits transcript us contaminate it presented an audio segments, batman arkham knight credits transcript during season of you get a franchise that. Spencer what batman arkham knight credits transcript ar combat focuses on batman transcript present agreed to! You will die the proud wolf you are. Miracles by their definition are meaningless, the Baron! He turns and FIRES. Rpgs are really need batman credits transcript legend embodies it. British man in batman knight had interacted with batman arkham knight credits transcript. An illustration of two cells of a film strip. This is just beautiful pieces and arkham credits transcript legend are bigger role model just want to arkham credits picks right up another fucking idiot. -

Justice League: Origins

JUSTICE LEAGUE: ORIGINS Written by Chad Handley [email protected] EXT. PARK - DAY An idyllic American park from our Rockwellian past. A pick- up truck pulls up onto a nearby gravel lot. INT. PICK-UP TRUCK - DAY MARTHA KENT (30s) stalls the engine. Her young son, CLARK, (7) apprehensively peeks out at the park from just under the window. MARTHA KENT Go on, Clark. Scoot. CLARK Can’t I go with you? MARTHA KENT No, you may not. A woman is entitled to shop on her own once in a blue moon. And it’s high time you made friends your own age. Clark watches a group of bigger, rowdier boys play baseball on a diamond in the park. CLARK They won’t like me. MARTHA KENT How will you know unless you try? Go on. I’ll be back before you know it. EXT. PARK - BASEBALL DIAMOND - MOMENTS LATER Clark watches the other kids play from afar - too scared to approach. He is about to give up when a fly ball plops on the ground at his feet. He stares at it, unsure of what to do. BIG KID 1 (yelling) Yo, kid. Little help? Clark picks up the ball. Unsure he can throw the distance, he hesitates. Rolls the ball over instead. It stops halfway to Big Kid 1, who rolls his eyes, runs over and picks it up. 2. BIG KID 1 (CONT’D) Nice throw. The other kids laugh at him. Humiliated, Clark puts his hands in his pockets and walks away. Big Kid 2 advances on Big Kid 1; takes the ball away from him. -

Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics Kristen Coppess Race Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Race, Kristen Coppess, "Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics" (2013). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 793. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/793 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BATWOMAN AND CATWOMAN: TREATMENT OF WOMEN IN DC COMICS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By KRISTEN COPPESS RACE B.A., Wright State University, 2004 M.Ed., Xavier University, 2007 2013 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Date: June 4, 2013 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Kristen Coppess Race ENTITLED Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics . BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. Thesis Director _____________________________ Carol Loranger, Ph.D. Chair, Department of English Language and Literature Committee on Final Examination _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. _____________________________ Carol Mejia-LaPerle, Ph.D. _____________________________ Crystal Lake, Ph.D. _____________________________ R. William Ayres, Ph.D. -

Tony Isabella: Black Thought

Tony Isabella: Black Thought Tony Isabella wants you to know he’s ticked off. For years the industry veteran has championed positive portrayals of black heroes in the pages of comic books. In his Comic Buyer’s Guide column, “Tony’s Tips”, and on the internet he’s raged about the lack of ethnic diversity in comics publishing and the stereotypical treatment of minority characters. So it should come as no surprise that the seasoned writer has taken issue with events in the recently released Green Arrow #31. In his eyes, his most beloved creation -- Black Lightning -- was transformed into a cold-blooded murderer. Black Lightning/Jefferson Pierce sprang from Isabella’s imagination in 1977 to become the first African-American superhero at DC to get his own title. Gifted with electro-magnetic powers, along with a strong sense of community and Christian morality, Jefferson Pierce was designed to be an enduring symbol of justice. But over the years Isabella has watched his original character become distorted, even as he continually slipped on and off DC radar. Black Lightning’s debut series, written by Isabella, only made it to issue #11 before it fell prey to massive cutbacks in 1978. A string of guest appearances in other books such as Detective Comics and the Justice League followed before Black Lightning found a new home with The Outsiders, a street-level superhero team led by Batman, in the mid- 1980’s. After The Outsiders ended in 1988, Black Lightning was again downgraded to guest star status. It wasn’t until 1995 that Jefferson Pierce became a consistent player in the DC universe again.