UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Librib 501200.Pdf

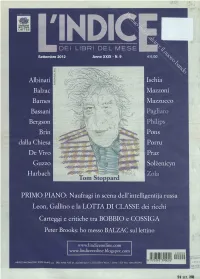

FONDAZIONE BOTTARI LATTES Settembre 2012 Anno XXIX - N. 9 Albinati Ischia Balzac Mazzoni Barnes Mazzucco Bassani Bergson Brin Pons dalla Chiesa Porru De Vivo Praz Guzzo Solzenicyn Harbach PRIMO PIANO: Naufragi in scena del?intelligenti)a russa Leon, Gallino e la LOTTA DI CLASSE dei ricchi Carteggi e critiche tra BOBBIO e COSSIGA Peter Brooks: ho messo BALZAC sul lettino www.lindiceonline.com www.lindiceonline.blogspot.com MENSILE D'INFORMAZIONE - POSTE ITALIANE s.p.a. - SPED. IN ABB. POST. D.L. 353/2003 (conv.in L. 27/02/2004 n° 46) art. I, comma ], DCB Torino - ISSN 0393-3903 Editoria La verità è destabilizzante Per Achille Erba di Lorenzo Fazio Quando è mancato Achille Erba, uno dei fon- ferimento costante al Vaticano II e all'episcopa- a domanda è: "Ma ci quere- spezzarne il meccanismo di pro- datori de "L'Indice", alcune persone a lui vicine to di Michele Pellegrino) sono ampiamente illu- Lleranno?". Domanda sba- duzione e trovare (provare) al- hanno deciso di chiedere ospitalità a quello che lui strate nel sito www.lindiceonline.com. gliata per un editore che si pre- tre verità. Come editore di libri, ha continuato a considerare Usuo giornale - anche È opportuna una premessa. Riteniamo si sarà figge il solo scopo di raccontare opera su tempi lunghi e incrocia quando ha abbandonato l'insegnamento universi- tutti d'accordo che le analisi e le discussioni vol- la verità. Sembra semplice, ep- passato e presente avendo una tario per i barrios di Santiago del Cile e, successi- te ad illustrare e approfondire nei suoi diversi pure tutta la complessità del la- prospettiva anche storica e più vamente, per una vita concentrata sulla ricerca - aspetti la ricerca storica di Achille e ad indivi- voro di un editore di saggistica libera rispetto a quella dei me- allo scopo di convocare un'incontro che ha lo sco- duare gli orientamenti generali che ad essa si col- di attualità sta dentro questa pa- dia, che sono quotidianamente po di ricordarlo, ma anche di avviare una riflessio- legano e che eventualmente la ispirano non pos- rola. -

Curriculum Vitae E Studiorum

GIULIA TELLINI CURRICULUM VITAE E STUDIORUM FORMAZIONE . Dottorato di ricerca in Storia dello Spettacolo, conseguito in data 16 maggio 2008 presso 1 l’Università degli Studi di Firenze, con tesi dal titolo Una carriera fra cinema e teatro: Gino Cervi nello spettacolo italiano fra primo e secondo dopoguerra, relatore prof. Siro Ferrone. Laurea in Lettere, conseguita in data 17 giugno 2004 presso l'Università degli Studi di Firenze, con tesi in Storia del Teatro e dello Spettacolo dal titolo Attrici per Medea. Interpretazioni del mito tra Otto e Novecento, relatore prof. Siro Ferrone, voto di laurea 110 Lode/110 (centodieci e lode su centodieci). ATTIVITÀ DI RICERCA E INSEGNAMENTI . Dal marzo 2017 è assegnista di ricerca in Letteratura Italiana, Dipartimento di Lettere e Filosofia dell'Università degli Studi di Firenze. Dal 2015 insegna Letteratura teatrale italiana presso l’Università Federico II di Napoli nell’ambito del Master di II livello in Drammaturgia e Cinematografia (12 ore all’anno). Dal 2014 insegna al Florence Program dell’Università di Toronto Mississauga presso l’Accademia Fiorentina di Lingua e Cultura Italiana (72 ore all’anno, fra metà settembre e metà novembre). Dal 2009 tiene il corso di Storia del Teatro italiano presso il Centro di Cultura per Stranieri dell’Università di Firenze (32 ore all’anno). Dall’estate 2008 insegna presso la Scuola Italiana del Middlebury College Language Schools (USA, Vermont e California): 30 ore ogni corso, fra fine giugno e inizio agosto. Nel 2004, 2011, 2012 e 2013, ha tenuto corsi di lingua italiana presso il Centro di Cultura per Stranieri dell’Università di Firenze. -

Organized Crime and Electoral Outcomes. Evidence from Sicily at the Turn of the XXI Century

Organized Crime and Electoral Outcomes. Evidence from Sicily at the Turn of the XXI Century Paolo Buonanno,∗ Giovanni Prarolo (corresponding author),y Paolo Vaninz November 4, 2015 Abstract This paper investigates the relationship between Sicilian mafia and politics by fo- cusing on municipality-level results of national political elections. It exploits the fact that in the early 1990s the Italian party system collapsed, new parties emerged and mafia families had to look for new political allies. It presents evidence, based on disaggregated data from the Italian region of Sicily, that between 1994 and 2013 Silvio Berlusconi’s party, Forza Italia, obtained higher vote shares at national elec- tions in municipalities plagued by mafia. The result is robust to the use of different measures of mafia presence, both contemporary and historical, to the inclusion of different sets of controls and to spatial analysis. Instrumenting mafia’s presence by determinants of its early diffusion in the late XIX century suggests that the correla- tion reflects a causal link. Keywords: Elections, Mafia-type Organizations JEL codes: D72, H11 ∗Department of Economics, University of Bergamo, Via dei Caniana 2, 24127 Bergamo, Italy. Phone: +39- 0352052681. Email: [email protected]. yDepartment of Economics, University of Bologna, Piazza Scaravilli 2, 40126 Bologna, Italy. Phone: +39- 0512098873. E-mail: [email protected] zDepartment of Economics, University of Bologna, Piazza Scaravilli 2, 40126 Bologna, Italy. Phone: +39- 0512098120. E-mail: [email protected] 1 1. Introduction The relationship between mafia and politics is a crucial but empirically under-investigated issue. In this paper we explore the connection between mafia presence and party vote shares at national political elections, employing municipality level data from the mafia-plagued Italian region of Sicily. -

Lessico Famigliare De Natalia Ginzburg E La Storia De

Dossiê Anuário de Literatura, ISSNe: 2175-7917, vol. 15, n. 2, 2010 Anuário de Literatura Volume 15 Número 02 OS RESTOS DA HISTÓRIA NOS ROMANCES: LESSICO FAMIGLIARE DE NATALIA GINZBURG E LA STORIA DE ELSA MORANTE Davi Pessoa Carneiro Doutorando em Literatura – UFSC/CAPES 260 Dossiê Anuário de Literatura, ISSNe: 2175-7917, vol. 15, n. 2, 2010 DOI: 10.5007/2175-7917.2010v15n2p260 REMNANTS OF HISTORY IN THE NOVELS: LESSICO FAMIGLIARE BY NATALIA GINZBURG AND LA STORIA BY ELSA MORANTE RESUMO: O objetivo deste artigo é confrontar os romances Lessico famigliare (1963) da escritora Natalia Ginzburg (1916-1991) e La Storia (1974) de Elsa Morante (1912-1985) com o intuito de pensar os excessos de poder da Segunda Guerra Mundial, de seus regimes totalitários e de seus reflexos presentes no universo familiar, afetivo e privado da sociedade italiana no entre e no pós-guerra. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Romance italiano; Segunda Guerra Mundial; Natalia Ginzburg; Elsa Morante. ABSTRACT: The objective of this article is to confront the novels Lessico famigliare (1963), by Natalia Ginzburg (1916-1991) and La Storia (1974), by Elsa Morante (1912-1985). The purpose is thinking about the excesses of power in World War II, its totalitarian regimes and their consequences to the familiar, affective and private universe of Italian society in the interwar and postwar periods. KEYWORDS: Italian novel; World War II; Natalia Ginzburg; Elsa Morante. 261 Dossiê Anuário de Literatura, ISSNe: 2175-7917, vol. 15, n. 2, 2010 Natalia Ginzburg, no artigo “I personaggi di Elsa” [As personagens de questões fundamentais para compreendermos os excessos de poder da Elsa], de 21 de julho de 1974, publicado no caderno Corriere Letterario, do Segunda Guerra Mundial, de seus regimes totalitários e de seus reflexos jornal Corriere della Sera, inicia o texto com as seguintes palavras: presentes no universo familiar, afetivo e privado. -

MARIO SOLDATI Tra Cinema E Letteratura (1906-1999)

Biblioteca Civica“Nicolò e Paola Francone” Sezione Storia Locale Via Vittorio Emanuele II, 1 – 10023 CHIERI tel. 011.9428406/400 – email: [email protected] MARIO SOLDATI tra cinema e letteratura (1906-1999) BIBLIOGRAFIA Nato a Torino nel 1906, Mario Soldati esordisce con la commedia Pilato (1924), ma si impone id=31004694 all’attenzione della critica con il libro di racconti Salmace (1929) e soprattutto con il diario del suo soggiorno negli Stati Uniti come insegnante alla Columbia University nel biennio 1929-31, America primo amore (1935).Tra i films da lui diretti, sempre con sobrietà e essenzialità espressiva si ricordano Piccolo mondo antico (1941) e Eugenia Grandet (1946). Ha partecipato alla sceneggiatura del kolossal hollywoodiano Guerra e Pace (1956). Muore a Tellaro il 19 giugno 1999 . È stato sicuramente un SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curSA 3.0, - protagonista, seppur discusso e controverso, della cultura italiana della prima e della seconda metà del Novecento, considerato un “personaggio” per il coraggio di conciliare la cultura cosiddetta propria,CC BY Opera - alta all’arte popolare e quindi allo spettacolo: ritenuto, da sempre, in ambito letterario un "buon narratore", non è stato solo uno scrittore di primissimo ordine, ma anche l’autore di alcuni capolavori del cinema italiano: è sempre stato annoverato tra i "registi intellettuali" o meglio tra gli Immagine di GorupdebesanezImmagine "intellettuali registi". Romanzi e racconti A cena col Commendatore , Milano, Mondadori, 1961. M.B.7229. Addio diletta Amelia , Milano, A. Mondadori, 1979. M.B.4011. Ah! il Mundial! Storia dell’inaspettabile , con una nota di Massimo Raffaeli, Palermo, Sellerio, 2008. -

Euroscepticism in Political Parties of Greece

VYTAUTAS MAGNUS UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND DIPLOMACY DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE Eimantas Kočanas EUROSCEPTICISM IN POLITICAL PARTIES OF GREECE Master’s Thesis Contemporary European politics study program, state code 621L20005 Political sciences study direction Supervisor: Prof. Doc. Mindaugas Jurkynas Defended: PMDF Dean - Prof. Doc. Šarūnas Liekis Kaunas 2016 European Union is like a painting displayed in a museum. Some admire it, others critique it, and few despise it. In all regards, the fact that the painting is being criticized only shows that there is no true way to please everybody – be it in art or politics. - Author of this paper. 1 Summary Eimantas Kocanas ‘Euroscepticism in political parties of Greece’, Master’s Thesis. Paper supervisor Prof. Doc. Mindaugas Jurkynas, Kaunas Vytautas Magnus University, Department of Diplomacy and Political Sciences. Faculty of Political Sciences. Euroscepticism (anti-EUism) had become a subject of analysis in contemporary European studies due to its effect on governments, parties and nations. With Greece being one of the nations in the center of attention on effects of Euroscepticism, it’s imperative to constantly analyze and research the eurosceptic elements residing within the political elements of this nation. Analyzing eurosceptic elements within Greek political parties, the goal is to: detect, analyze and evaluate the expressions of Euroscepticism in political parties of Greece. To achieve this: 1). Conceptualization of Euroscepticism is described; 2). Methods of its detection and measurement are described; 3). Methods of Euroscepticism analysis are applied to political parties of Greece in order to conclude what type and expressions of eurosceptic behavior are present. To achieve the goal presented in this paper, political literature, on the subject of Euroscepticism: 1). -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses TERRONI AND POLENTONI: WHERE DOES THE TRUTH LIE? AN ANTHROPOLOGY OF SOCIAL NETWORKS AND ETHNICITY IN PALERMO (SICILY), ITALY. PARDALIS, STERGIOS How to cite: PARDALIS, STERGIOS (2009) TERRONI AND POLENTONI: WHERE DOES THE TRUTH LIE? AN ANTHROPOLOGY OF SOCIAL NETWORKS AND ETHNICITY IN PALERMO (SICILY), ITALY. , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/289/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 TERRONI AND POLENTONI: WHERE DOES THE TRUTH LIE? AN ANTHROPOLOGY OF SOCIAL NETWORKS AND ETHNICITY IN PALERMO (SICILY), ITALY. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN DECEMBER 2009 TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND HEALTH OF DURHAM UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY Stergios Pardalis Stergios Pardalis: ‘Terroni and Polentoni: Where Does the Truth Lie? An Anthropology of Social Networks and Ethnicity in Palermo (Sicily), Italy. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Between the Local and the National: the Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2014 Between the Local and the National: The Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty Fabio Capano Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Capano, Fabio, "Between the Local and the National: The Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty" (2014). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5312. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5312 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between the Local and the National: the Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianità," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty Fabio Capano Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Modern Europe Joshua Arthurs, Ph.D., Co-Chair Robert Blobaum, Ph.D., Co-Chair Katherine Aaslestad, Ph.D. -

History and Emotions Is Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena

NARRATING INTENSITY: HISTORY AND EMOTIONS IN ELSA MORANTE, GOLIARDA SAPIENZA AND ELENA FERRANTE by STEFANIA PORCELLI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 STEFANIA PORCELLI All Rights Reserved ii Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante by Stefania Porcell i This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Comparative Literature in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Chair of Examining Committee ________ ______________________________ Date [Giancarlo Lombardi] Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Monica Calabritto Hermann Haller Nancy Miller THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Narrating Intensity: History and Emotions in Elsa Morante, Goliarda Sapienza and Elena Ferrante By Stefania Porcelli Advisor: Giancarlo Lombardi L’amica geniale (My Brilliant Friend) by Elena Ferrante (published in Italy in four volumes between 2011 and 2014 and translated into English between 2012 and 2015) has galvanized critics and readers worldwide to the extent that it is has been adapted for television by RAI and HBO. It has been deemed “ferocious,” “a death-defying linguistic tightrope act,” and a combination of “dark and spiky emotions” in reviews appearing in popular newspapers. Taking the considerable critical investment in the affective dimension of Ferrante’s work as a point of departure, my dissertation examines the representation of emotions in My Brilliant Friend and in two Italian novels written between the 1960s and the 1970s – La Storia (1974, History: A Novel) by Elsa Morante (1912-1985) and L’arte della gioia (The Art of Joy, 1998/2008) by Goliarda Sapienza (1924-1996). -

E42 Mark Blyth & David Kertzer Mixdown

Brown University Watson Institute | E42_Mark Blyth & David Kertzer_mixdown [MUSIC PLAYING] MARK BLYTH: Hello, and welcome to a special edition of Trending Globally. My name is Mark Blyth. Today, I'm interviewing David Kertzer. David is the former provost here at Brown University. But perhaps more importantly, he knows more about Italy than practically anybody else we can find. Given that the elections have just happened in Italy and produced yet another kind of populist shock, we thought is was a good idea to bring him in and have a chat. Good afternoon, David. DAVID KERTZER: Thanks for having me, Mark. MARK BLYTH: OK, so let's try and put this in context for people. Italy's kicked off. Now, we could talk about what's happening right now today, but to try and get some context on this, I want to take us back a little bit. This is not the first time the Italian political system-- indeed the whole Italian state-- has kind of blown up. I want to go back to 1994. That's the last time things really disintegrated. Start there, and then walk forward, so then we can talk more meaningfully about the election. So I'm going to invite you to just take us back to 1994. Tell us about what was going on-- the post-war political compact, and then [BLOWS RASPBERRY] the whole thing fell apart. DAVID KERTZER: Well, right after World War II, of course, it was a new political system-- the end of the monarchy. There is a republic. The Christian Democratic Party, very closely allied with the Catholic Church, basically dominated Italian politics for decades. -

Community, Place, and Cultural Battles: Associational Life in Central Italy, 1945-1968

Community, Place, and Cultural Battles: Associational Life in Central Italy, 1945-1968 Laura J. Hornbake Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 2013 Laura J. Hornbake This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. ABSTRACT Community, Place, and Cultural Battles: Associational Life in Central Italy, 1945-1968 Laura J. Hornbake This dissertation is an exploration of associational life in central Italy, an examination of organizations that were central to the everyday experience of tens of thousands of Italians at a time when social, economic and geographical transformations were upending their everyday lives, 1945-1968. This dissertation examines facets of these transformations: the changing shape of cities, increasing mobility of people, technological changes that made possible new media and new cultural forms, from the perspective of local associations. The many lively groups, the cultural circles and case del popolo of central Italy were critical sites where members encountered new ideas, navigated social change, and experimented with alternative cultures. At the same time, these organizations themselves were being transformed from unitary centers that expressed the broad solidarity of the anti-fascist Resistance to loose federations of fragmentary single-interest groups. They were tangles of intertwined politics, culture, and community, important sites in culture