Specimens of Cornish Provincial Dialect (1889)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes on the Parish of Mylor, Cornwall

C.i i ^v /- NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR /v\. (crt MVI.OK CII r RCII. -SO UIH I'OKCil AND CROSS O !• ST. MlLoKIS. [NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR CORNWALL. BY HUGH P. OLIVEY M.R.C.S. Uaunton BARNICOTT &- PEARCE, ATHEN^UM PRESS 1907 BARNICOTT AND PEARCE PRINTERS Preface. T is usual to write something as a preface, and this generally appears to be to make some excuse for having written at all. In a pre- face to Tom Toole and his Friends — a very interesting book published a few years ago, by Mrs. Henry Sandford, in which the poets Coleridge and Wordsworth, together with the Wedgwoods and many other eminent men of that day figure,—the author says, on one occasion, when surrounded by old letters, note books, etc., an old and faithful servant remon- " " strated with her thus : And what for ? she " demanded very emphatically. There's many a hundred dozen books already as nobody ever reads." Her hook certainly justified her efforts, and needed no excuse. But what shall I say of this } What for do 1 launch this little book, which only refers to the parish ot Mylor ^ vi Preface. The great majority of us are convinced that the county of our birth is the best part of Eng- land, and if we are folk country-born, that our parish is the most favoured spot in it. With something of this idea prompting me, I have en- deavoured to look up all available information and documents, and elaborate such by personal recollections and by reference to authorities. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Chris Dunkerley\My Documents\Excel

CORNISH ASSOCIATION OF NSW - MEMBERS LENDING & RESEARCH LIBRARY - Jan 2008 Search using Edit, Find in this page (Firefox) For more information or to borrow contact Eddie or Eileen Lyon on: (02) 9349 1491 or Email: [email protected] Id No BOOK NAME AUTHOR DESCRIPTION 1 Yesterday's Town: St Ives Noall Cyril Book - illustrated history 2 King Arthur Country in Cornwall Duxbury & Williams Book - information 3 Story of St Ives, The Noall Cyril Book 4 St Ives in the 1800's Laity R.P. Book 5 Cornish Surnames, A Handbook of G. Pawley White Book 6 Cornish Pioneers of Ballarat Dell & Menhennet Book 7 Kernewek for Kids Franklin Sharon Book - Copper Triangle Puzzles, Stories 8 Australian Celtic Journal Vol.One Darlington J Journal 9 Microform Collection Index (OUT OF CIRCULATION) Aust. Soc of Genealogy Journal 10 Where Now Cousin Jack? Hopkins Ruth Book 11 Cornwall - A Genealogical Bibliography Raymond Stuart Journal LOST 12 Penwith - The Illustrated Past Noall Cyril Book 13 St Ives, The Book of Noall Cyril Book - pictorial history LOST IN FIRE 14 Cornish Names Dexter T.F.G. Book 15 Scilly and the Scillonians Read A.H. & Son Book - pictorial history 16 Shipwrecks at Land's End Larn & Mills Book 17 Minerals, Rocks and Gemstones in Cornwall Rogers Cedric Book - collector’s guide 18 King Arthur, Tintagel Castle & Celtic Monuments Tintagel Parish Council Book 19 Shipwrecks on the Isles of Scilly Gibson F.E. Book 20 Which Francis Symonds Symonds John Symonds history - Cornwall and Australia 21 St Ives, The Beauty of Badger H.G. Illustration Booklet 22 Little Land of Cornwall, The Rowse A.L. -

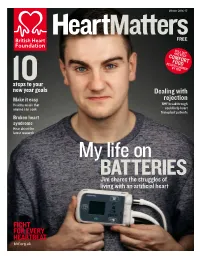

My Life on BATTERIES Jim Shares the Struggles of Living with an Artificial Heart

Winter 2016-17 FREE PULL OUT AND KEEP COMFORT RECIPESFOOD CHOSEN BY YOU 10steps to your new year goals Dealing with Make it easy rejection Healthy meals that BHF breakthrough anyone can cook could help heart transplant patients Broken heart syndrome Hear about the latest research My life on BATTERIES Jim shares the struggles of living with an artificial heart FIGHT FOR EVERY HEARTBEAT bhf.org.uk It’s a new year, a time for new beginnings. We’re here to help with that. Check out our advice for setting goals and sticking to them on page 40. Sometimes, new beginnings happen in difficult circumstances. Having a heart condition can change life as you know it, but it is possible to discover a different, yet still fulfilling, way of life. On page 37, Claire Marie Berouche explains how she managed to adapt after being diagnosed with heart failure, and we get tips from experts on how to do this. Our cover star Jim Lynskey is hoping 2017 will be the year he gets a new heart. Read his moving story on page 10. Professor Federica Marelli-Berg is an expert on the immune system who recently became a British Heart Foundation Professor – one of our most senior researchers. What does immunology have to do with the heart, you might wonder. Well, research like this could help people, like Jim, who need heart transplants, reducing the risk of their new heart being rejected. The BHF spends more than £100m a year on research. As well as the immune system, we’re funding research into diseases of the kidneys, eyes, lungs, brain and more. -

The Evolving Relationship Between Food and Tourism: a Case Study Of

1 THE EVOLVING RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FOOD AND TOURISM: A CASE STUDY OF DEVON THROUGH THE TWENTIETH CENTURY Submitted by: Paul Edward Cleave, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Management Studies. November 2011 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without prior acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature............................................. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank everyone who contributed so generously and patiently of their time and expertise in the completion of this thesis, and especially to my supervisor, Professor Gareth Shaw for his guidance and inspiration. Their unfailing support and encouragement in my endeavours is greatly appreciated. Paul Cleave 3 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to examine the evolving relationship between food and tourism through the twentieth century. Devon, a county in the South West of England, and a popular tourist destination is used as the geographical focus of the case study. Previous studies have tended to focus on particular locations at a fixed point in time, not over the timescale of a century. The research presents a social and economic history of food in the context of tourism. It incorporates many food related interests reflecting the topical and evolving, embracing leisure, pleasure and social history, Burnett (2004). -

A Poetics of Uncertainty: a Chorographic Survey of the Life of John Trevisa and the Site of Glasney College, Cornwall, Mediated Through Locative Arts Practice

VAL DIGGLE: A POETICS OF UNCERTAINTY A poetics of uncertainty: a chorographic survey of the life of John Trevisa and the site of Glasney College, Cornwall, mediated through locative arts practice By Valerie Ann Diggle Page 1 VAL DIGGLE: A POETICS OF UNCERTAINTY VAL DIGGLE: A POETICS OF UNCERTAINTY A poetics of uncertainty: a chorographic survey of the life of John Trevisa and the site of Glasney College, Cornwall, mediated through locative arts practice By Valerie Ann Diggle Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of the Arts London Falmouth University October 2017 Page 2 Page 3 VAL DIGGLE: A POETICS OF UNCERTAINTY VAL DIGGLE: A POETICS OF UNCERTAINTY A poetics of uncertainty: a chorographic survey of the life of John Trevisa and the site of Glasney College, Penryn, Cornwall, mediated through locative arts practice Connections between the medieval Cornishman and translator John Trevisa (1342-1402) and Glasney College in Cornwall are explored in this thesis to create a deep map about the figure and the site, articulated in a series of micro-narratives or anecdotae. The research combines book-based strategies and performative encounters with people and places, to build a rich, chorographic survey described in images, sound files, objects and texts. A key research problem – how to express the forensic fingerprint of that which is invisible in the historic record – is described as a poetics of uncertainty, a speculative response to information that teeters on the brink of what can be reliably known. This poetics combines multi-modal writing to communicate events in the life of the research, auto-ethnographically, from the point of view of an artist working in the academy. -

History of Cornish Dance and Its Origins

History of Cornish Dance Folk dance is more than just a collection of steps movement and music; it is a form of human expression and its essence lies within its community role and social context rather than purely commercial or artistic interests. Sharp was riding the crest of European romantic nationalism when he collected, and mediated, folk dances as an expression of Englishness in the first quarter of the twentieth century. At much the same time there was a parallel, but Celtic, revivalist movement in Cornwall. As well as identifying with the revival of the Cornish language and links with the other Celtic communities this movement was also pro-active in recording and promoting folk customs, including dance. The story of folk dance in Cornwall, from medieval roots, through narratives of the nineteenth Century folklorists, the activity of the Celtic revivalists and on to the present day, is a fascinating one that reflects the distinct cultural profile of Cornwall. A tantalising glimpse of medieval dance in Cornwall is provided a twelfth Century Cornish / Latin vocabulary which was written to aid the learning of Latin. It is a short vocabulary of common words people were expected to be familiar with and includes the translation of the Cornish lappior as saltator and lappiores as saltatrix; male and female dancer respectively. Lapyeor continued to be used as a dialect term for dancer in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and by the early twentieth century was associated with step dancing. It is poignant to learn that the small boys employed as surface workers in the tin industry were called lapyeors because one of their first tasks was to aid separation of the ore as it was washed by “dancing” on it ankle deep in the cold water. -

Tam Kernewek

Tam Kernewek “ A bit of Cornish” Volume 32 Issue 3 Fall 2014 Cornish American Heritage Society Cornish American Heritage 48 Presidents’ Messages I can't believe the excitement of the 17th Gathering is over! It has been a whirlwind and a great success. The Cornish Society of Greater Milwaukee pulled it off well, if I do say so myself. Thanks to all the great presenters and Cornish Cous- ins who really made it a family reunion. It was a pleasure meeting many names I had only read before. I am so happy that Kathryn Herman has agreed to take over as president. After two years of working with her on the plan- ning committee, I know she is a woman of great organization and imagination. Her knowledge of Cornwall and connec- tions there will give the CAHS a direction I couldn't give. I will be happy to continue serving as an officer (historian), so I can work on projects for the Society. As I hand over the role of president to Kathryn, I will be finishing up some things started at the Gathering. (And Kathryn deserves to catch her breath!) Our business meeting was cut short. Ultimately that may be an advantage, since some questions might be better addressed via e-mails with the participants, rather than a hurried discussion we would have had there. If any of the CAHS members not present at the Gathering would like to be included in the discussion, please write me. Again, thanks to all for the great Gathering! It is now a matter of continuing the energy we had in Milwaukee. -

Jack Clemo 1916-55: the Rise and Fall of the 'Clay Phoenix'

1 Jack Clemo 1916-55: The Rise and Fall of the ‘Clay Phoenix’ Submitted by Luke Thompson to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English In September 2015 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. 2 Abstract Jack Clemo was a poet, novelist, autobiographer, short story writer and Christian witness, whose life spanned much of the twentieth century (1916- 1994). He composed some of the most extraordinary landscape poetry of the twentieth century, much of it set in his native China Clay mining region around St Austell in Cornwall, where he lived for the majority of his life. Clemo’s upbringing was one of privation and poverty and he was famously deaf and blind for much of his adult life. In spite of Clemo’s popularity as a poet, there has been very little written about him, and his confessional self-interpretation in his autobiographical works has remained unchallenged. This thesis looks at Clemo’s life and writing until the mid-1950s, holding the vast, newly available and (to date) unstudied archive of manuscripts up against the published material and exploring the contrary narratives of progressive disease and literary development and success. -

London Cornish Newsletter

Cowethas Kernewek Loundres www.londoncornish.co.uk For the LCA, this summer has had several identify this game from this rather vague Dates for your highlights, beginning with the Countryside description? My keywords have drawn a Parade which took place in Cornwall as part blank on google! diary of the celebrations to mark the Duke of As already mentioned, the main reason for Cornwall’s 70th birthday. The Association Family History Day our visit to Cornwall was to attend the 13th October 2018 was represented by our Chairman, Carol Gorsedd Awards Ceremony. Nominations Goodwin and members ‘Cilla Oates and for two of the Awards – the Pewas Map 10am to 4pm Don and Catherine Foster. Following this, Trevethan (Paul Smales Award) and the Pre-Christmas Lunch there were two pub lunches, a visit to the London Cornish Association Shield - are Richmond Rowing Club to meet up with coordinated by a Committee which includes 8th December 2018 members of the London Cornish Pilot Gig the President and some Vice-Presidents of 12 noon Association and, for some, attendance at the LCA. The Committee make recommen- the Rosyer Lecture at City Lit. dations but the final decision on the awards New Year’s Lunch At the end of August, several of us attended is made by the Gorsedd. 12th January 2019 12 noon the Gorsedd Awards Ceremony in New- We are now calling for nominations (with quay where our Chairman and Treasurer supporting motivation) for the 2019 awards: both received Awards from the Grand Bard. Further details of This was a proud moment for both the The Pewas Map Trevethan Award is pre- these events can be awardees and their friends and family. -

London Cornish Newsletter

Cowethas Kernewek Loundres www.londoncornish.co.uk The Piskeys crept in – but a tive. The only ‘complaint’ was about the size of the font. We apologise for happy outcome ensued that as we had not anticipated the original copy would be shrunk by Family History Day, Welcome to the Spring 2019 edition half, and therefore did not prepare AGM and Trelawny of the LCA newsletter. for it. That is easily corrected, and Lecture - 13th April, You will notice that our last newslet- this issue is going off with a larger 10am-4.30pm font size – so hopefully all will be ter – and now this Spring issue – Rugby Union Match well from now on. look different to those from the past. – Cornish Pirates Apart from an increase in the font About the time you receive this vs London Scottish size in future (sorry to those who newsletter, we will be celebrating St RFC - 13th April , struggled with the Winter copy!), this Piran’s Day with a cream tea at a 3pm will be our new format. London hotel, and just two weeks Two big changes were introduced later, following the success of our Mid-Summer Lunch with the winter newsletter – the intro- Annual Dining Event last year, we 6th July, 12 noon duction of coloured pictures in the will return to the same hotel where hard copy, and the reduction in page we look forward to another excellent July events tbc: size. While the coloured pictures meal and a very enjoyable after- were planned, the change in size noon. County Finals day at was not. -

Noun Phrase Analysis

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická fakulta Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky TRADITIONAL BRITISH COOKING – NOUN PHRASE ANALYSIS Bakalářská práce Autor: David Dorotík Vedoucí práce: Prof. PhDr. Jaroslav Macháček, CSc. Olomouc 2014 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně a uvedl úplný seznam citované a použité literatury. V Olomouci dne 5. 5. 2014 …..………………….. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Prof. PhDr. Jaroslav Macháček, CSc., for his kind support and valuable advice. Table of Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 6 2 The English Noun Phrase ......................................................................................... 7 2.1 Structure of a noun phrase ............................................................................... 7 2.2 Head of a noun phrase ....................................................................................... 8 2.2.1 Typical noun phrase head categories ............................................................ 8 2.2.2 Adjectives as heads of noun phrases ............................................................. 8 2.3 Determiners ........................................................................................................ 9 2.4 Premodification of a noun phrase .................................................................... 9 2.4.1 Types of English noun phrase premodifiers ................................................ -

LIFE in CORNWALL in a Village Called Herland Cross, Cornwall

Alma Ward Hampton Memoir Page 1 LIFE IN CORNWALL In a village called Herland Cross, Cornwall, England, lived John Hampton (born about 1814), who married Elizabeth Curtis (Born about 1818). John rented or leased land which was near Godolphin Cross where the owner of the Estate lived, which contained a house and shed and land enough to keep a few cows and chickens. Over the years they had three sons and three daughters, John, Grace, William, Annie, James and Elizabeth. William known as Billy, who eventually came to Maple Ridge in the year 1879, was born February 19, 1854, and it is his story that will be related. For centuries Cornwall has been famous for its copper, tin and lead, and ships came from afar to obtain them. In those times work was provided for women and children at the surface which they called "the Bal a Celtic name for "mine place". Ore was brought up and placed on tables and was then broken into small pieces with hammers. At an early age, Billy did this work, until he was old enough to go down into a mine to work. At this time it was tin that was mined. The men went down the mine shaft in a bucket to a great depth. Sometimes they were given a fast ride for a prank, which was rather scary. Here he learned how to hammer in the iron drill, which they called a needle, to make a hole for the gunpowder for blasting. In the early days they used a goose quill for the fuse.