Noun Phrase Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Wedding Day at Buchan Braes Hotel

Your Wedding Day at Buchan Braes Hotel On behalf of all the staff we would like to congratulate you on your upcoming wedding. Set in the former RAF camp, in the village of Boddam, the building has been totally transformed throughout into a contemporary stylish hotel featuring décor and furnishings. The Ballroom has direct access to the landscaped garden which overlooks Stirling Hill, making Buchan Braes Hotel the ideal venue for a romantic wedding. Our Wedding Team is at your disposal to offer advice on every aspect of your day. A wedding is unique and a special occasion for everyone involved. We take pride in individually tailoring all your wedding arrangements to fulfill your dreams. From the ceremony to the wedding reception, our professional staff take great pride and satisfaction in helping you make your wedding day very special. Buchan Braes has 44 Executive Bedrooms and 3 Suites. Each hotel room has been decorated with luxury and comfort in mind and includes all the modern facilities and luxury expected of a 4 star hotel. Your guests can be accommodated at specially reduced rates, should they wish to stay overnight. Our Wedding Team will be delighted to discuss the preferential rates applicable to your wedding in more detail. In order to appreciate what Buchan Braes Hotel has to offer, we would like to invite you to visit the hotel and experience firsthand the four star facilities. We would be delighted to make an appointment at a time suitable to yourself to show you around and discuss your requirements in more detail. -

Irish Corned Beef: a Culinary History

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Articles School of Culinary Arts and Food Technology 2011-04-01 Irish Corned Beef: A Culinary History Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire Technological University Dublin, [email protected] Pádraic Óg Gallagher Gallagher's Boxty House, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/tfschafart Recommended Citation Mac Con Iomaire, M. and P. Gallagher (2011) Irish Corned Beef: A Culinary History. Journal of Culinary Science and Technology. Vol 9, No. 1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Culinary Arts and Food Technology at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Irish Corned Beef: A Culinary History ABSTRACT This article proposes that a better knowledge of culinary history enriches all culinary stakeholders. The article will discuss the origins and history of corned beef in Irish cuisine and culture. It outlines how cattle have been central to the ancient Irish way of life for centuries, but were cherished more for their milk than their meat. In the early modern period, with the decline in the power of the Gaelic lords, cattle became and economic commodity that was exported to England. The Cattle Acts of 1663 and 1667 affected the export trade of live cattle and led to a growing trade in salted Irish beef, centred principally on the city of Cork. -

Notes on the Parish of Mylor, Cornwall

C.i i ^v /- NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR /v\. (crt MVI.OK CII r RCII. -SO UIH I'OKCil AND CROSS O !• ST. MlLoKIS. [NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR CORNWALL. BY HUGH P. OLIVEY M.R.C.S. Uaunton BARNICOTT &- PEARCE, ATHEN^UM PRESS 1907 BARNICOTT AND PEARCE PRINTERS Preface. T is usual to write something as a preface, and this generally appears to be to make some excuse for having written at all. In a pre- face to Tom Toole and his Friends — a very interesting book published a few years ago, by Mrs. Henry Sandford, in which the poets Coleridge and Wordsworth, together with the Wedgwoods and many other eminent men of that day figure,—the author says, on one occasion, when surrounded by old letters, note books, etc., an old and faithful servant remon- " " strated with her thus : And what for ? she " demanded very emphatically. There's many a hundred dozen books already as nobody ever reads." Her hook certainly justified her efforts, and needed no excuse. But what shall I say of this } What for do 1 launch this little book, which only refers to the parish ot Mylor ^ vi Preface. The great majority of us are convinced that the county of our birth is the best part of Eng- land, and if we are folk country-born, that our parish is the most favoured spot in it. With something of this idea prompting me, I have en- deavoured to look up all available information and documents, and elaborate such by personal recollections and by reference to authorities. -

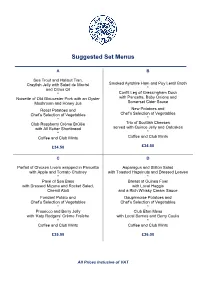

Scottish Menus

Suggested Set Menus A B Sea Trout and Halibut Tian, Crayfish Jelly with Salad de Maché Smoked Ayrshire Ham and Puy Lentil Broth and Citrus Oil * * Confit Leg of Gressingham Duck Noisette of Old Gloucester Pork with an Oyster with Pancetta, Baby Onions and Somerset Cider Sauce Mushroom and Honey Jus Roast Potatoes and New Potatoes and Chef’s Selection of Vegetables Chef’s Selection of Vegetables * * Club Raspberry Crème Brûlée Trio of Scottish Cheeses with All Butter Shortbread served with Quince Jelly and Oatcakes * * Coffee and Club Mints Coffee and Club Mints £34.50 £34.50 C D Parfait of Chicken Livers wrapped in Pancetta Asparagus and Stilton Salad with Apple and Tomato Chutney with Toasted Hazelnuts and Dressed Leaves * * Pavé of Sea Bass Breast of Guinea Fowl with Dressed Mizuna and Rocket Salad, with Local Haggis Chervil Aïoli and a Rich Whisky Cream Sauce Fondant Potato and Dauphinoise Potatoes and Chef’s Selection of Vegetables Chef’s Selection of Vegetables * * Prosecco and Berry Jelly Club Eton Mess with ‘Katy Rodgers’ Crème Fraîche with Local Berries and Berry Coulis * * Coffee and Club Mints Coffee and Club Mints £35.00 £36.00 All Prices Inclusive of VAT Suggested Set Menus E F Confit of Duck, Guinea Fowl and Apricot Rosettes of Loch Fyne Salmon, Terrine, Pea Shoot and Frissée Salad Lilliput Capers, Lemon and Olive Dressing * * Escalope of Seared Veal, Portobello Mushroom Tournedos of Border Beef Fillet, and Sherry Cream with Garden Herbs Fricasée of Woodland Mushrooms and Arran Mustard Château Potatoes and Chef’s Selection -

Dinner Menus

Accommodation, Conferences and Events DINNER MENUS If you are looking for a unique guest experience, our team of professional caterers will strive to deliver the exceptional service you expect from the University of St Andrews. Our staff take pride in delivery of each individual event, be it a continental breakfast for twelve people, a wedding breakfast for fifty to a gala dinner for three hundred. With a passion for flair, the catering and events team will work with you to create the menu you desire to complement any theme or goals, or you can choose from our range of specifically designed options to suit your event. Whatever your choice, the calibre of food and service provided will be delivered with a personal investment from each of our team members to ensure that your event is special and memorable. DINNER MENU Dinner selector STARTER Sweet potato and coconut soup Curry oil drizzle (v) £5.00 Marinated vine-ripened tomato and baby mozzarella salad Basil infused oil (v) £6.00 Pickled pear salad Walnut soil and blue cheese (v) £5.75 Classic chicken liver pâté Fruit chutney and smoked Scottish oatcake £5.95 Gin-cured salmon Soda bread, lime and tonic aioli £6.50 Haggis, neeps and tatties Malt whisky sauce £5.50 Pan seared scallop Pea purée and pancetta oil £6.75 All prices are inclusive of VAT Food allergens and intolerances: If you have a food allergen or intolerance, prior to placing your order, please highlight this with us and we can guide you through our menu. University of St Andrews t: +44 (0) 1334 463000 e: [email protected] w: ace.st-andrews.ac.uk The University of St Andrews is a charity registered in Scotland, No: SC013532. -

A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1998 A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770 Mollie C. Malone College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Malone, Mollie C., "A Dinner at the Governor's Palace, 10 September 1770" (1998). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626149. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-0rxz-9w15 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A DINNER AT THE GOVERNOR'S PALACE, 10 SEPTEMBER 1770 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mollie C. Malone 1998 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 'JYIQMajl C ^STIclU ilx^ Mollie Malone Approved, December 1998 P* Ofifr* * Barbara (farson Grey/Gundakerirevn Patricia Gibbs Colonial Williamsburg Foundation TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv ABSTRACT V INTRODUCTION 2 HISTORIOGRAPHY 5 A DINNER AT THE GOVERNOR’S PALACE, 10 SEPTEMBER 1770 17 CONCLUSION 45 APPENDIX 47 BIBLIOGRAPHY 73 i i i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to thank Professor Barbara Carson, under whose guidance this paper was completed, for her "no-nonsense" style and supportive advising throughout the project. -

Hot & Cold Fork Buffets

HOT & COLD FORK BUFFETS Option 1- Cold fork buffet- £14.00 + vat - 2 cold platters, 3 salads and 1 sweet Option 2 - £15.50 + VAT - 1 Main Course (+ 1 Vegetarian Option), 1 Sweet Option 3 - £22.00 + VAT - 2 Main Course (+ 1 Vegetarian Option), 2 Salads, 2 Sweets Add a cold platter and 2 salads to your menu for £5.25 + VAT per person. Makes a perfect starter. COLD PLATTERS Cold meat cuts (Ayrshire ham, Cajun spiced chicken fillet and pastrami Platter of smoked Scottish seafood) Scottish cheese platter with chutney and Arran oaties (Supplement £4 pp & vat) Duo of Scottish salmon platter (poached and teriyaki glazed) Moroccan spice roasted Mediterranean vegetables platter MAINS Collops of chicken with Stornoway black pudding, Arran mustard mash potatoes and seasonal greens Baked seafood pie topped with parmesan mash, served with steamed buttered greens Tuscan style lamb casserole with tomato, borlotti beans and rosemary with pan fried polenta Roast courgette and aubergine lasagne with roasted Cajun spiced sweet potato wedges Jamaican jerk spice rubbed pork loin with spiced cous cous and honey and lime roasted carrots. Chicken, peppers and chorizo casserole in smoked paprika cream with roasted Mediterranean vegetables and braised rice Balsamic glazed salmon fillets with steamed greens and baby potatoes with rosemary, olive oil and sea salt Haggis, neeps and tatties, served with a whisky sauce Braised mini beef olives with sausage stuffing in sage and onions gravy with creamed potatoes All prices exclusive of VAT. Menus may be subject to change -

We're A' Jock Tamson's Bairns

Some hae meat and canna eat, BIG DISHES SIDES Selkirk and some wad eat that want it, Frying Scotsman burger £12.95 Poke o' ChipS £3.45 Buffalo Farm beef burger, haggis fritter, onion rings. whisky cream sauce & but we hae meat and we can eat, chunky chips Grace and sae the Lord be thankit. Onion Girders & Irn Bru Mayo £2.95 But 'n' Ben Burger £12.45 Buffalo Farm beef burger, Isle of Mull cheddar, lettuce & tomato & chunky chips Roasted Roots £2.95 Moving Munros (v)(vg) £12.95 Hoose Salad £3.45 Wee Plates Mooless vegan burger, vegan haggis fritter, tomato chutney, pickles, vegan cheese, vegan bun & chunky chips Mashed Tatties £2.95 Soup of the day (v) £4.45 Oor Famous Steak Pie £13.95 Served piping hot with fresh baked sourdough bread & butter Steak braised long and slow, encased in hand rolled golden pastry served with Champit Tatties £2.95 roasted roots & chunky chips or mash Cullen skink £8.95 Baked Beans £2.95 Traditional North East smoked haddock & tattie soup, served in its own bread Clan Mac £11.95 bowl Macaroni & three cheese sauce with Isle of Mull, Arron smoked cheddar & Fresh Baked Sourdough Bread & Butter £2.95 Parmesan served with garlic sourdough bread Haggis Tower £4.95 £13.95 FREEDOM FRIES £6.95 Haggis, neeps and tatties with a whisky sauce Piper's Fish Supper Haggis crumbs, whisky sauce, fried crispy onions & crispy bacon bits Battered Peterhead haddock with chunky chips, chippy sauce & pickled onion Trio of Scottishness £5.95 £4.95 Haggis, Stornoway black pudding & white pudding, breaded baws, served with Sausage & Mash -

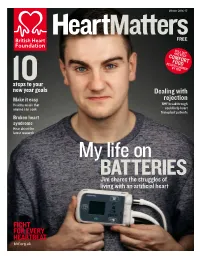

My Life on BATTERIES Jim Shares the Struggles of Living with an Artificial Heart

Winter 2016-17 FREE PULL OUT AND KEEP COMFORT RECIPESFOOD CHOSEN BY YOU 10steps to your new year goals Dealing with Make it easy rejection Healthy meals that BHF breakthrough anyone can cook could help heart transplant patients Broken heart syndrome Hear about the latest research My life on BATTERIES Jim shares the struggles of living with an artificial heart FIGHT FOR EVERY HEARTBEAT bhf.org.uk It’s a new year, a time for new beginnings. We’re here to help with that. Check out our advice for setting goals and sticking to them on page 40. Sometimes, new beginnings happen in difficult circumstances. Having a heart condition can change life as you know it, but it is possible to discover a different, yet still fulfilling, way of life. On page 37, Claire Marie Berouche explains how she managed to adapt after being diagnosed with heart failure, and we get tips from experts on how to do this. Our cover star Jim Lynskey is hoping 2017 will be the year he gets a new heart. Read his moving story on page 10. Professor Federica Marelli-Berg is an expert on the immune system who recently became a British Heart Foundation Professor – one of our most senior researchers. What does immunology have to do with the heart, you might wonder. Well, research like this could help people, like Jim, who need heart transplants, reducing the risk of their new heart being rejected. The BHF spends more than £100m a year on research. As well as the immune system, we’re funding research into diseases of the kidneys, eyes, lungs, brain and more. -

Introduction to Baking and Pastries Chef Tammy Rink with William R

Introduction to Baking and Pastries Chef Tammy Rink With William R. Thibodeaux PH.D. ii | Introduction to Baking and Pastries Introduction to Baking and Pastries | iii Introduction to Baking and Pastries Chef Tammy Rink With William R. Thibodeaux PH.D. iv | Introduction to Baking and Pastries Introduction to Baking and Pastries | v Contents Preface: ix Introduction to Baking and Pastries Topic 1: Baking and Pastry Equipment Topic 2: Dry Ingredients 13 Topic 3: Quick Breads 23 Topic 4: Yeast Doughs 27 Topic 5: Pastry Doughs 33 Topic 6: Custards 37 Topic 7: Cake & Buttercreams 41 Topic 8: Pie Doughs & Ice Cream 49 Topic 9: Mousses, Bavarians and Soufflés 53 Topic 10: Cookies 56 Notes: 57 Glossary: 59 Appendix: 79 Kitchen Weights & Measures 81 Measurement and conversion charts 83 Cake Terms – Icing, decorating, accessories 85 Professional Associations 89 vi | Introduction to Baking and Pastries Introduction to Baking and Pastries | vii Limit of Liability/disclaimer of warranty and Safety: The user is expressly advised to consider and use all safety precautions described in this book or that might be indicated by undertaking the activities described in this book. Common sense must also be used to avoid all potential hazards and, in particular, to take relevant safety precautions concerning likely or known hazards involving food preparation, or in the use of the procedures described in this book. In addition, while many rules and safety precautions have been noted throughout the book, users should always have adult supervision and assistance when working in a kitchen or lab. Any use of or reliance upon this book is at the user's own risk. -

Dam Event Room

Dam Event Room As you may or may not know, we are actually boat people. We have been running the passenger boat in De Pere since 2015 and the one in Appleton since 2018. We love bringing people to the water!! That is the reason we started the Bistro, to be able to do just that, all year around. Our years of planning events on the boats bring a bit of a different way to run events. We do whatever it takes to help you have the best event that you can possibly have and know that you will enjoy it just that much more because you held it by the river! Part of that enjoyment comes from us making sure that the process is as stress-free as possible. As if you were simply holding the gathering in your favorite aunt’s house, (or on her boat) - very comfortable and easy. That being said, have no fear, because your aunt is a wonderful chef! Our kitchen crew will create the culinary experience that you envision, or even better. We are blessed to have them on our team! Now, we bet you would like some information! Hopefully, we answer most of your questions below. Dam Room Accommodations: · Newly renovated gathering place in the historic Atlas Mill along the Fox River in Appleton, WI · Wonderful views of the rushing water just below the dam, bringing you the sights and sounds of the river like no other place in the area! · Local, custom built, reclaimed maple and steel dining tables · Padded, sturdy non-folding wood chairs · Depending on group size, access to hand crafted pottery · Capacity for 2021 is 55. -

At the Tee Par 3 Lighter Fare Salads & Soups

At The Tee Nachos 14.99 full, 10.99 half Cheese Sticks 5.99 seasoned beef or chicken, cheddar cheese, breaded cheese wedges, marinara sauce diced tomatoes, black olives, green chiles, onions Hot Wings 15.99 (12), 12.99 (9), 9.99 (6) add: sour cream 1.00 · salsa 1.50 · guacamole spicy drumettes, celery, carrots, 2.00 bleu cheese or ranch dressing Quesadilla 10.99 Bruschetta 7.99 fajita seasoned chicken or beef taco meat, Roma tomatoes, basil, balsamic reduction, flour tortilla, diced tomatoes, black olives, on crostini crisps green chiles, onions, cheddar cheese, jack cheese Zucchini & Cheese Sticks 9.99 beer battered, ranch, marinara sauce add: sour cream 1.00 · guacamole 2.00 Potato Chips 2.99 Potato Skins 5.99 freshly cut potato chips, ranch dressing six potato skins, bacon, cheddar cheese, mozzarella, green onions Beer Battered Onion Rings 6.99 ranch dressing Par 3 Lighter Fare Salads & Soups Taco Salad 11.99 Asian Chicken Salad* 11.99 seasoned ground beef, romaine lettuce, sliced chicken breast, almonds, diced tomatoes, onions, black olives, mandarin orange slices, crispy noodles, cheddar cheese, sour cream, salsa mixed greens, toasted sesame dressing add: guacamole 2.00 Chef Salad 11.99 Cajun Cobb Salad* 11.99 turkey, ham, hardboiled egg, cheddar cheese, sliced Cajun chicken breast, diced tomatoes, swiss, diced tomatoes, cucumbers, bacon bits, black olives, carrots, mixed greens, thousand island dressing hardboiled egg, cucumbers, bleu cheese, mixed greens House Salad 3.99 diced tomatoes, cheddar cheese, croutons Cajun Chicken Caesar Salad* 11.99 sliced Cajun chicken breast, diced tomatoes, Soup of the Day croutons, Caesar dressing 2.99 (cup), 4.99 (bowl) *Can be cooked to order.