The Evolving Relationship Between Food and Tourism: a Case Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategic Policies

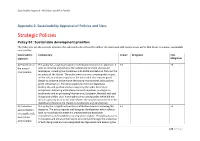

Sustainability Appraisal - Mid Devon Local Plan Review Appendix 2: Sustainability Appraisal of Policies and Sites Strategic Policies Policy S1: Sustainable development priorities The Policy sets out the strategic priorities that will need to be achieved to deliver the vision and address key issues within Mid Devon to support sustainable communities. Sustainability Commentary Impact Mitigation Post objective Mitigation A) Protection of This policy has a significant positive contribution towards this objective. It +3 +3 the natural aims to conserve and enhance the natural environment and valued environment landscapes, including the Blackdown Hills AONB and National Parks on the periphery of the district. The policy aims to prevent unacceptable impact on the soil, air and water quality in the area and it also requires good design to conserve and enhance the natural environment and supports green infrastructure. The policy aspires to minimise impacts on biodiversity and geodiversity by recognising the wider benefits of ecosystems, delivering natural environment objectives, a net gain in biodiversity and by protecting International, European, National and local designated wildlife sites. It strengthens the existing policy which did not include a priority to conserve and enhance the natural environment or the objective to minimise the impact on biodiversity and geodiversity. B) Protection This policy has a significant positive contribution towards achieving this +3 +3 and promotion objective. The policy requires well designed development which -

Financial Literacy: an Essential Tool for Informed Consumer Choice?

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES FINANCIAL LITERACY: AN ESSENTIAL TOOL FOR INFORMED CONSUMER CHOICE? Annamaria Lusardi Working Paper 14084 http://www.nber.org/papers/w14084 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 June 2008 I would like to thank Keith Ernst, Howell Jackson, Kevin Rhein, Peter Tufano, and participants to the conference "Understanding Consumer Credit: A National Symposium on Expanding Access, Informing Choices, and Protecting Consumers," Harvard Business School, November 2007, and the conference "Consumer Information and the Mortgage Market," Federal Trade Commission, Washington, D.C., May 2008 for suggestions and comments. This paper builds on several projects I have written in collaboration with Olivia Mitchell, whom I would like to thank for her encouragement, support, and many suggestions. Audrey Brown provided excellent research assistance. Any errors are my responsibility. This paper was written while visiting Harvard Business School and I would like to thank them, and in particular Peter Tufano, for their hospitality. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Annamaria Lusardi. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Financial Literacy: An Essential Tool for Informed Consumer Choice? Annamaria Lusardi NBER Working Paper No. -

Sediment Yields in the Exe Basin: a Longer-Term Perspective

Sediment Dynamics and the Hydromorphology of Fluvial Systems (Proceedings of a symposium held in 12 Dundee, UK, July 2006). IAHS Publ. 306, 2006. Sediment yields in the Exe Basin: a longer-term perspective ANNA HARLOW, BRUCE WEBB & DES WALLING School of Geography, Archaeology and Earth Resources, Department of Geography, Amory Building, Rennes Drive, Exeter EX4 4RJ, UK [email protected] Abstract In the UK, fine sediment is viewed increasingly as a diffuse pollu- tant due to its role as a vector for the transport of potential contaminants, and in causing siltation, which may have adverse effects on river and estuarine habitats. There is a need, therefore, for river managers to have reliable information on sediment budgets in order to plan measures that will achieve “good” status under the EU Water Framework Directive. As part of a wider sediment-budget investigation in the EU-funded Cycleau Project, detailed records of fine sediment yield over the 10-year period from 1994–2003 have been analysed for the Exe Basin (1500 km2), a principal river system of southwest England. The longer-term average yields in the three major tributaries of the Exe Basin are discussed and results of monitoring of sediment loads at a site near the tidal limit over a one-year period confirm the importance of the River Exe in contributing sediment to the Estuary. Key words diffuse pollution; Exe Basin and estuary; longer-term behaviour; suspended sediment yields INTRODUCTION River systems provide a key pathway along which fine sediment (silt and clay particles of <63 µm in diameter) is transferred from the terrestrial to the estuarine environment. -

The William Cole Archive on Stained Glass Roundels for the Corpus Vitrearum

THE WILLIAM COLE ARCHIVE ON STAINED GLASS ROUNDELS FOR THE CORPUS VITREARUM Contents of the Archive NB All material is arranged alphabetically. Listed Material 1. List of Place Files: British, Overseas - arranged alphabetically according to place. Tours - arranged chronologically. 2. List of Articles by William Cole, draft and published material. 3. List of Correspondence with Museums and Organisations. 4. List of Articles about Stained Glass Roundels by other Authors. 5. List of Photographs from various Museums and Collections. 6. List of Slides. 7. Correspondence: A-G, H-P, Q-Z (listed) General, with individuals (unlisted) Unlisted Material 8. Notebooks, cassettes and manuscripts made by William Cole. 9. Corpus Vitrearum conferences. 10. A range of guidebooks and pamphlets. 11. Box of iconography reference cards. 12. William Cole‟s card index of Netherlandish and North European Roundels, by place. 1 1a. Place files Place Location Catalogue Contents of file reference Addington St Mary the Virgin, 7–73 Draft article [WC] Buckinghamshire Correspondence Alfrick St Mary Magdalene, 74–90 Correspondence Hereford & Worcester Banwell St Andrew, Avon 113–119 Correspondence Begbroke St Michael, Oxfordshire 120–137 Correspondence Berwick-upon- Holy Trinity, 138–165 Correspondence Tweed Northumberland Birtles St Catherine, Cheshire 166–211 Draft article [WC] Bishopsbourne St Mary, Kent 212–239 Correspondence Blundeston St Mary, Suffolk 236–239 Correspondence Bradford-on- Holy Trinity, Wiltshire 251–275 Correspondence Avon Photocopied images Bramley -

Environment Agency – Community Flood Plan Contents

Parishes and communities working together Community Crediton Address Council Offices, 8A North Street, Crediton, EX17 2BT or group Floodline Quickdial 0345 988 1188 Which Environment Agency Mid Devon Rivers - Flood Alerts for the Rivers Number flood warnings are you Creedy, Creedy Yeo, Little Dart, Lapford Yeo and registered to receive? their tributaries Local flood warning trigger Environment Agency Flood Alert for Mid Devon Rivers OR Met Office Severe Weather Warning for i.e. when water reaches bottom of the bridge Rain Date 17th December 2018 Environment Agency – Community Flood Plan Contents 1. Actions to be taken before a flood A - Locations at risk of flooding: flood warnings B - Locations at risk of flooding: locations at risk of flooding / sources of flooding C - Locations at risk of flooding: map showing direction of flooding 2. Actions to be taken during a flood A - Local flood actions B - Local volunteers / flood wardens C - Important telephone numbers D - Available resources E - Arrangements between authorities F - Vulnerable residents, properties and locations 3. After a flood A - Reputable contractors Environment Agency – Community Flood Plan 1A – Locations at risk of flooding: Flood warnings Area no. Location of risk Trigger level Actions Area 1 Fordton Met Office weather warnings or • Alert your CRT to the rainfall forecast especially if heavy rain has started. Environment Agency flood warnings. • CRT to check adequate equipment in store. • CRT to advice community to be prepared to protect properties. Flood Alert issued for River Yeo • Start local observations. Signs to watch for include: ➢ Heavy rain and/or severe weather reports ➢ Rainfall not draining away, leading to surface water flooding ➢ Rising river levels, with dark churning water ➢ A build-up of debris in rivers, which could give way and cause a water surge • Consider starting the activation procedure and incident log (Annex E of Emergency Plan) Area 2 A377 (From Met Office weather warnings or • Alert your CRT to the rainfall forecast especially if heavy rain has started. -

Tourist Accommodation Diffusion in the Balearics, 1936-2010

Island Studies Journal , Vol. 9, No. 2, 2014, pp. 239-258 Tourism capitalism and island urbanization: tourist accommodation diffusion in the Balearics, 1936-2010. Antoni Pons Universitat de les Illes Balears, Spain [email protected] Onofre Rullán Salamanca Universitat de les Illes Balears, Spain [email protected] & Ivan Murray Universitat de les Illes Balears, Spain [email protected] ABSTRACT: The Balearic Islands are one of the main tourism regions in Europe, and tourism has been the structural capitalist activity of urban growth there since the 1950s. Mapping tourist accommodation in the Balearics might help spatially explain the important socio-spatial transformation of a small archipelago in the Western Mediterranean. This paper analyses the diffusion of tourist accommodations as the main vehicle for urbanization since the 1950s. The tourism production of space has gone in parallel to economic cycles with particular urban expressions related to the different regimes of accumulation. Over time, as access to sea, air, and road transport, availability of investment capital, and institutional support has changed, so too have the directions of urban tourism development in the islands. Keywords : Balearic Islands, diffusion, economic cycles, Spain, tourism, tourist accommodation maps, urbanization © 2014 - Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. Introduction Urbanization occurs differently on different kinds of islands. Islands specializing in tourism services may feature distinctive urbanization patterns due to the dynamics of this particular industry, which involves a coincidence between spaces of production and consumption. The spatial factors affecting islands play a variety of roles here, both increasing the amount of coastline (which has proven so attractive to mass tourism) and conditioning the means of transport and access to tourism sites. -

Notes on the Parish of Mylor, Cornwall

C.i i ^v /- NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR /v\. (crt MVI.OK CII r RCII. -SO UIH I'OKCil AND CROSS O !• ST. MlLoKIS. [NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR CORNWALL. BY HUGH P. OLIVEY M.R.C.S. Uaunton BARNICOTT &- PEARCE, ATHEN^UM PRESS 1907 BARNICOTT AND PEARCE PRINTERS Preface. T is usual to write something as a preface, and this generally appears to be to make some excuse for having written at all. In a pre- face to Tom Toole and his Friends — a very interesting book published a few years ago, by Mrs. Henry Sandford, in which the poets Coleridge and Wordsworth, together with the Wedgwoods and many other eminent men of that day figure,—the author says, on one occasion, when surrounded by old letters, note books, etc., an old and faithful servant remon- " " strated with her thus : And what for ? she " demanded very emphatically. There's many a hundred dozen books already as nobody ever reads." Her hook certainly justified her efforts, and needed no excuse. But what shall I say of this } What for do 1 launch this little book, which only refers to the parish ot Mylor ^ vi Preface. The great majority of us are convinced that the county of our birth is the best part of Eng- land, and if we are folk country-born, that our parish is the most favoured spot in it. With something of this idea prompting me, I have en- deavoured to look up all available information and documents, and elaborate such by personal recollections and by reference to authorities. -

Where Did They Go

BRITISH ‘BABY BOOMER’ NOSTALGIA Compiled by David Challinor Saluting AA Men Cream on Milk The Children’s Newspaper Shaving in Barbers Time Guns Foot X-Ray Machines in Shoe Shops Pea Shooters Pushers-up Same Day Post Passing Bells Subscription Libraries Boxing Kangaroos Dunces Caps Home-made Fireworks Aluminium Nameplate Machines at Stations German Bands Breton Onion Sellers Romany Caravans Ceiling Clocks Paint Boxes Electric Shock Therapy Bona Fide Travellers Bird – Nesting Apache Dancing Audiphones Aunt Sallies John Bull Puncture Repair Outfits & Printing sets Office Boys White Sugar Mice Camp Coffee Crystal Radio Sets Gas Mantles Guineas Boys Shouting the News Life Preservers Liquorice Imps/ Sherbet Pipes and Dabs Lobby Lud Cigarette Cards Driving Cattle through Towns Tripe Shops Continuous Performance School Ink, Inkwells and Ink Monitors Paper Chases Skipping Seasonal Children’s Games (conkers, marbles) Muffin Men Gob-stoppers Rag and Bone Men (goldfishes for junk) Beetle Drives Card Indexes in Libraries Change Receptacles on Overhead Wire Pulleys Reins on Toddlers Silver Cigarette Cases ‘Fly-proof’ Metal Grilles on Meat-safes Sticky Fly Paper DDT Memory Men (Leslie Welch) Kewpie Dolls Cigarette Holders Bells to Call the Chambermaid in hotel rooms Children’s Gardens Music Halls Pierrots/Black and White Minstrels School Milk Empire Day Pork Butchers Polite Children Blackberrying Laxative Chocolate Tuck Shops Ticking Clocks Flying Boats Rubber Bathing Caps Train Spotting Buying Pickles by the Basin Motor Cycle Sidecars Milk Churns Errand -

Blavatsky Will Instruct Me in the Seven Sacred Trances

Thomas Stearns Eliot Blavatsky will instruct me in the seven sacred trances Blavatsky will instruct me in the Seven Sacred Trances v. 19.10, www.philaletheians.co.uk, 1 February 2019 Page 1 of 3 BLAVATSKY TRIBUTES SERIES T.S. ELIOT ON THE SEVEN SACRED TRANCES 1 A Cooking Egg En l’an trentiesme de mon aage 2 Que toutes mes hontes j’ay beues . Pipit sate upright in her chair Some distance from where I was sitting; Views of the Oxford Colleges Lay on the table, with the knitting. Daguerreotypes and silhouettes, Her grandfather and great great aunts, Supported on the mantelpiece An Invitation to the Dance. I shall not want Honour in Heaven For I shall meet Sir Philip Sidney And have talk with Coriolanus And other heroes of that kidney. I shall not want Capital in Heaven For I shall meet Sir Alfred Mond. We two shall lie together, lapt In a five per cent. Exchequer Bond. I shall not want Society in Heaven, Lucretia Borgia shall be my Bride; Her anecdotes will be more amusing Than Pipit’s experience could provide. 1 First appeared in T.S. Eliot’s second collection of Poems, 1919. For a short analysis of the poem click here. 2 i.e., “By the 30th year of my life, I have drunk up all my shame,” epigraph from François Villon, the best known French poet of the late Middle Ages. Blavatsky will instruct me in the Seven Sacred Trances v. 19.10, www.philaletheians.co.uk, 1 February 2019 Page 2 of 3 BLAVATSKY TRIBUTES SERIES T.S. -

Sacrificing Privacy for Convenience: the Need for Stricter FTC Regulations in an Age of Smartphone Surveillance

Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary Volume 34 Issue 2 Article 6 12-15-2014 Sacrificing Privacy for Convenience: The Need for Stricter FTC Regulations in an Age of Smartphone Surveillance Ashton McKinnon Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/naalj Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Consumer Protection Law Commons, Privacy Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Ashton McKinnon, Sacrificing Privacy for Convenience: The Need for Stricter FTC Regulations in an Age of Smartphone Surveillance, 34 J. Nat’l Ass’n Admin. L. Judiciary 484 (2014) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/naalj/vol34/iss2/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judiciary by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Sacrificing Privacy for Convenience: The Need for Stricter FTC Regulations in an Age of Smartphone Surveillance By Ashton McKinnon* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 486 II. THE SMARTPHONE .................................................................... 488 III. APPS ........................................................................................ -

Consuming Fin De Siécle London: Female Consumers in Dorothy Richardson’S Pilgrimage

Wenshan Review of Literature and Culture.Vol 4.1.December 2010.57-80. Consuming Fin de Siécle London: Female Consumers in Dorothy Richardson’s Pilgrimage Han-sheng Wang ABSTRACT As an emerging site of female consumption, the West End of London in the fin de siècle period registers especially women‟s greater mobility in public consuming spaces. Along the central streets of the West End, with its mushrooming of shops, department stores, theaters, cafés, female clubs, and cinemas around the turn of the century, women increasingly manifest their visibility as purchasers, pleasure-seekers, and window-shoppers on the public street and the hetero-social urban space. Established during the same time, situated in the same neighborhood, and courting the same consuming public, these institutions address middle-class women as target customers and, through inviting them to purchase goods and services, contribute to the disruption of the long-held Victorian separate spheres and to the increased female public visibility at the turn of the century. This paper would thus examine female consumption as manifesting fin de siècle women‟s complicated involvement in the city‟s consuming spaces and commodity culture, which is represented by Dorothy Richardson in her fictional narratives about female consumers emerging in fin de siècle London, a phenomenon historically experienced by women of the 1880s and 1890s who increasingly found London‟s West End a site of consumption and female pleasure. KEY WORDS: Dorothy Richardson, Female Consumption, Fin de Siècle London, -

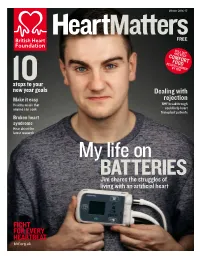

My Life on BATTERIES Jim Shares the Struggles of Living with an Artificial Heart

Winter 2016-17 FREE PULL OUT AND KEEP COMFORT RECIPESFOOD CHOSEN BY YOU 10steps to your new year goals Dealing with Make it easy rejection Healthy meals that BHF breakthrough anyone can cook could help heart transplant patients Broken heart syndrome Hear about the latest research My life on BATTERIES Jim shares the struggles of living with an artificial heart FIGHT FOR EVERY HEARTBEAT bhf.org.uk It’s a new year, a time for new beginnings. We’re here to help with that. Check out our advice for setting goals and sticking to them on page 40. Sometimes, new beginnings happen in difficult circumstances. Having a heart condition can change life as you know it, but it is possible to discover a different, yet still fulfilling, way of life. On page 37, Claire Marie Berouche explains how she managed to adapt after being diagnosed with heart failure, and we get tips from experts on how to do this. Our cover star Jim Lynskey is hoping 2017 will be the year he gets a new heart. Read his moving story on page 10. Professor Federica Marelli-Berg is an expert on the immune system who recently became a British Heart Foundation Professor – one of our most senior researchers. What does immunology have to do with the heart, you might wonder. Well, research like this could help people, like Jim, who need heart transplants, reducing the risk of their new heart being rejected. The BHF spends more than £100m a year on research. As well as the immune system, we’re funding research into diseases of the kidneys, eyes, lungs, brain and more.