Irish Corned Beef: a Culinary History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

At the Tee Par 3 Lighter Fare Salads & Soups

At The Tee Nachos 14.99 full, 10.99 half Cheese Sticks 5.99 seasoned beef or chicken, cheddar cheese, breaded cheese wedges, marinara sauce diced tomatoes, black olives, green chiles, onions Hot Wings 15.99 (12), 12.99 (9), 9.99 (6) add: sour cream 1.00 · salsa 1.50 · guacamole spicy drumettes, celery, carrots, 2.00 bleu cheese or ranch dressing Quesadilla 10.99 Bruschetta 7.99 fajita seasoned chicken or beef taco meat, Roma tomatoes, basil, balsamic reduction, flour tortilla, diced tomatoes, black olives, on crostini crisps green chiles, onions, cheddar cheese, jack cheese Zucchini & Cheese Sticks 9.99 beer battered, ranch, marinara sauce add: sour cream 1.00 · guacamole 2.00 Potato Chips 2.99 Potato Skins 5.99 freshly cut potato chips, ranch dressing six potato skins, bacon, cheddar cheese, mozzarella, green onions Beer Battered Onion Rings 6.99 ranch dressing Par 3 Lighter Fare Salads & Soups Taco Salad 11.99 Asian Chicken Salad* 11.99 seasoned ground beef, romaine lettuce, sliced chicken breast, almonds, diced tomatoes, onions, black olives, mandarin orange slices, crispy noodles, cheddar cheese, sour cream, salsa mixed greens, toasted sesame dressing add: guacamole 2.00 Chef Salad 11.99 Cajun Cobb Salad* 11.99 turkey, ham, hardboiled egg, cheddar cheese, sliced Cajun chicken breast, diced tomatoes, swiss, diced tomatoes, cucumbers, bacon bits, black olives, carrots, mixed greens, thousand island dressing hardboiled egg, cucumbers, bleu cheese, mixed greens House Salad 3.99 diced tomatoes, cheddar cheese, croutons Cajun Chicken Caesar Salad* 11.99 sliced Cajun chicken breast, diced tomatoes, Soup of the Day croutons, Caesar dressing 2.99 (cup), 4.99 (bowl) *Can be cooked to order. -

Wedding-Food-Drink-Menus-2018.Pdf

1 The Wedding Promise At As You Like It we guarantee... 1. Whatever your wedding dream - tastefully traditional or daringly different - we deliver. 2. Your day will be all wrapped up in a big bundle of fun. 3. You’re in safe hands - we are the experts. 4. Incredible deals for every budget. “There is no sincerer love than the love of food.” George Bernard Shaw 2 Fabulous Food 3 Course Wedding Breakfast Prices start from £40.95 per person mains (plus a vegetarian choice!) and two desserts for all your guests. We get as much of our produce from local suppliers as we can! We are also able to cater for any kind of dietary requests - please just ask. (Some of our dishes may contain traces of nuts or may have come into contact with nuts) 3 Canapés Our canapés are perfectly presented to add an allure of splendor from the start. Tiny but tasty, these treat sized tempatations are sure to be an impressive addition to the start of your day. 3 canapés per person = £5 Extra canapé = £1 supplement per person Served cold Asian style crab tartlets Smoked chicken and wholegrain mustard tarts with fresh herbs Beef crostini with onion jam & horseradish Whipped goats cheese & red onion tart (v) Chicken & wild mushroom tart with fresh herbs BBQ pulled pork crostini with braised red cabbage (gf) Fresh strawberries dipped with white & dark chocolate dipping sauces (v) Served hot Cheese fritters with tomato chutney (v) Mini fishcakes with dill crème fraiche Crispy Thai rice ball, coriander & lime mayonnaise (v) Spiced tomato & mozzarella arancini ball with pesto -

Corned Beef: an Enigmatic Irish Dish

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Conference papers School of Culinary Arts and Food Technology 2011-01-01 Corned Beef: An Enigmatic Irish Dish Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire Technological University Dublin, [email protected] PFollowadraig this Og and Gallagher additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/tfschcafcon Gallagher's Boxty House, [email protected] Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Corned beef and cabbage, which is consumed in America in large quantities each Saint Patrick’s Day (17th March), is considered by most Americans to be the ultimate Irish dish. However, corned beef and cabbage is seldom eaten in modern day Ireland. It is widely reported that Irish immigrants replaced their beloved bacon and cabbage with corned beef and cabbage when they arrived in America, drawing on the corned beef supplied by their neighbouring Jewish butchers, but not all commentators believe this simplistic explanation . This paper will trace the origins and history of corned beef in Irish cuisine and chart how this dish came to represent Irish cuisine in America. The name corned beef originates in seventeenth century England, derived from corns – or small crystals – of salt used to salt or cure the meat. The paper will discuss the anomaly that although corned beef was not widely eaten in Ireland, it was widely exported, becoming one of Ireland’s leading food exports, mostly from the city of Cork. Irish corned beef provisioned the British navy fleets for over two centuries and was also shipped to the colonies. There is evidence of a strong trade in Irish corned beef as a staple for African slaves in the French West Indies and in other French colonies. -

BREAKFAST Served 24 Hours Traditional Club Breakfasts*

BREAKFAST Served 24 hours Traditional Club Breakfasts* Served with hash browns and your choice of toast, English muffin, piping hot blueberry or lemon-cranberry muffin, or toasted bagel with cream cheese. Substitute Egg Beaters or egg whites for $2.25. COUNTRY STYLE HAM AND EGGS .....................................$16.95 16 oz. flame-broiled bone-in ham steak, served with three farm fresh eggs TURKEY SAUSAGE AND EGGS ...........................................$13.95 Served with hash browns and choice of toast or muffin BACON or SAUSAGE or CANADIAN BACON AND EGGS ..$13.50 Three farm fresh eggs served with your choice of four slices of bacon, three sausage links or three slices of Canadian bacon NEW YORK STEAK AND EGGS ..........................................$19.95 SOUTHERN FRIED STEAK AND EGGS .................................$16.95 Our delicious breaded country fried steak covered in country sausage gravy, served with 3 farm fresh eggs cooked any style Peppermill Breakfast Favorites* WESTERN FRUIT PLATE .......................................................$15.95 Accompanied by fresh banana-nut bread and Peppermill’s creamy marshmallow sauce EGGS BENEDICT ...............................................................$14.95 3 poached eggs on grilled Canadian bacon and toasted English muffin, topped with Hollandaise sauce, served with hash browns GRANOLA AND YOGURT PARFAIT ......................................$10.25 Layers of low fat yogurt, seasonal fruit and granola CHORIZO AND EGGS .......................................................$13.95 Delicious spicy Mexican sausage scrambled into three farm fresh eggs, served with refried beans and warm flour tortillas BISCUITS AND GRAVY .........................................................$8.95 Freshly baked biscuits smothered in country sausage gravy JOE’S SAN FRANCISCO SPECIAL .......................................$13.95 Traditional classic of scrambled eggs with spinach, onion, ground beef and sausage, seasoned and served on crispy hash browns and topped with a golden cheese sauce. -

2013 Winners

Blas na hEireann – 2013 Winners Supreme Champion sponsored by Bord Bia An Olivia Chocolate Best Artisan sponsored by The Taste Council Skeaghanore West Cork Duck Best Export Opportunity sponsored by Enterprise Ireland Heavenly Tasty Organics Best New Product sponsored by Invest NI Gold - Glorious Sushi – Lecho Sauce Silver – Couverture Desserts – Couverture Shot Dessert Selection Bronze – Waldron Meats – Glazed Cook in the Bag Bacon Joint UCC Best Packaging Award Bewleys for their Espresso Bean Packaging Packaging Development Bursary – Sponsored by Love Irish Food O’Sullivan’s Bakery AIB Business Diversification Award Hartnetts Oils Rogha na Gaeltachta Bluirini Blasta Seafood Innovation Iasc - Seafood Butter Best in County Limerick – Sponsored by Limerick County Enterprise Board Best Emerging Producer in County Limerick – Green Apron Best in Farmers Market, Limerick – Ballyhoura Best in Tipperary - Sponsored by Tipp North County & Tipp South Riding Enterprise Boards Best Emerging Producer, Tipperary – O’Donnells – Presented by Eleanor Forrest Best in Farmer’s Market, Tipperary – Lough Derg Chocolates – Presented by Eleanor Forrest Best in County Waterford - Sponsored by Waterford County Enterprise Board Best Emerging Producer in County Waterford – Glorious Sushi Best in Farmer’s Market, Waterford – Biddy Gonzales Best In Cork – Sponsored by Cork County & City Enterprise Boards Best Emerging Producer in Cork – Wicked Desserts Best in Farmer’s Market, Cork – On the Pig’s Back Best In Kerry – Sponsored by Kerry County Enterprise Board Best -

LUNCH MENU STARTERS and LIGHT BITES GOURMET SANDWICHES SUPER SALADS Roast of the Day

LUNCH MENU STARTERS AND LIGHT BITES GOURMET SANDWICHES SUPER SALADS Roast of the Day ...............................................€13.50 Today’s roast served with potatoes, seasonal vegetables and sauce (Please ask your server) Allergens 7, 9 and 12 Soup of the day ................................................€5.95 Our gourmet sandwiches are freshly Classic Caesar Salad.......................................€10.50 Daily made soup served with homemade brown made to order with a salad garnish Crisp baby gem leaves tossed with our house Caesar bread dressing, ciabatta croutons, crispy bacon and aged Vegetable Fajitas .............................................€13.50 Allergens 6 wheat, 7 and 12 Irish Gammon .....................................................€6.50 Parmesan shavings Seasonal vegetables lightly spiced, served on a Slow cooked, with mustard mayo on homemade Add Irish chargrilled chicken.....................€13.50 sizzler with flour tortillas, sour cream, guacamole and soda bread Spring Rolls ........................................................ 6.50 Allergens 3 anchovies, 6 wheat, 7, 11, 12 and 13 fine salad € Allergens 6 wheat, 7, 11, 12 and 13 Allergens 6 wheat, 7 and 13 Vegetable spring rolls, pickled cucumber, soy and chilli dipping sauces West Cork Seafood .........................................€14.95 “Tom Durcan’s Spiced Beef” ..................... 6.50 Allergens 6 wheat, 8, 12 and 13 € Freshly poached Irish salmon, crabmeat and mango, Tomato and Lemon Risotto ........................€13.00 An award winning spiced beef with homemade North Atlantic prawn with Marie Rose sauce, mixed Sun-blushed tomatoes, zesty lemon, baby rocket and apple chutney on sourdough baby leaves, lemon and aioli dressing Chicken Wings ................................................. 7.50 a drizzle of fresh basil pesto € Allergens 6 wheat, 7, 11 and 13 Allergens 1 and 2 prawn, crab, 3 salmon and 11, 12 and 13 Allergens 5 pine nuts, 7, 9 and 12 Crispy Irish chicken wings, Cashel Blue cheese (Co. -

IRISH FOOD and Recipes

IRISH FOOD and recipes 1-Classify these Irish products in your food pyramid. Write the number corresponding to the category. Then, write the names in English. 6 5 4 3 2 1 … … … … ……………………. ……………… ………………….. ………………………… … … … … ………………. ……………….. …………………. ……………………… … … … … … ……………………….. ………………… ……………… ……………. ………………. cabbage – potatoes – turnips – onions – parsley – mussels - salmon lamb/mutton (sheep) - pork (pig) - beef (cow) – cheese – butter - cream 2-Match the picture of the traditional Irish dish with the corresponding definition. … … … … … … 1- Irish stew 2- Bacon and cabbage 3- Spiced beef (Irish: “stobhach”) (Irish: “bágún agus cabáiste”) (Irish: mairteoil spíosraithe) It is a traditional Irish dish which The dish consists of sliced back It is traditionally served at consists of meat and root bacon boiled with cabbage and Christmas or the New Year. It is a vegetables. Common ingredients potatoes. It is often served with form of salt beef, cured with spices include lamb, or mutton, as well as white sauce, which consists of and saltpetre, and is usually boiled, potatoes, onions, parsley, and, flour, butter and milk, sometimes broiled or semi-steamed in water, sometimes carrots. with a flavouring of some sort and then optionally roasted for a (often parsley). period after. 4- Boxty 5- Seafood chowder 6- Colcannon (Irish: bacstaí) (Irish “Seabhdar”) (Irish: “cál ceannann”) It is a traditional Irish potato It is a particular method of It is a traditional Irish dish of pancake. The most popular version preparing a seafood soup, often mashed potatoes with kale or of the dish consists of finely grated, served with milk or cream. It cabbage. It can contain other raw potato and mashed potato with consists of onions, potatoes, ingredients such as scallions (spring flour, baking soda, buttermilk and haddock, salmon, mussels, cream, onions), leeks, onions. -

Blood Pudding, Beetroot, Boxty and Blaa Dublin Raises Irish Cuisine to New Heights, Emphasizing Local Specialties and Ingredients

PROOF User: 140617 Time: 16:54 - 01-22-2014 Region: SundayAdvance Edition: 1 8 TR THE NEW YORK TIMES, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 2014 CHOICE TABLES DUBLIN Blood Pudding, Beetroot, Boxty and Blaa Dublin raises Irish cuisine to new heights, emphasizing local specialties and ingredients. By DAVID FARLEY Stoneybatter, the main street that runs through the working-class neighborhood of the same name in north Dublin, is lined with traditional pubs. L. Mulligan Grocer, as its name suggests, is housed in a former pub and food shop. And it fits right in: A long bar, lined with taps, dominates the right side of the room. But venture toward the back, walk up three steps, and you’ll find something less predictable: a packed dining room of 19 tables, diners feasting on dishes like pan-fried hake in a carrot purée, as servers scurry past. The gastro pub, a movement that began across the Irish Sea in London, took a sur- prisingly long time to take hold here. Opened in 2010, L. Mulligan Grocer was among the first wave of gastro pubs in a city that is now dotted with them. It also happens to be serving some of the most ex- citing food in Dublin. But it’s not just gastro pubs that are stir- ring up the Irish capital’s dining scene. Cuisine in post-Celtic Tiger Dublin has adopted an inward gaze, with new restau- rants, both pubs and upscale bistros, em- phasizing locally sourced ingredients and offering creative takes that celebrate Irish cuisine in a variety of ways. -

Catering-Menu.Pdf

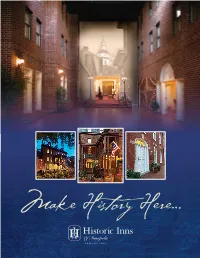

Make History Here… Thank you for considering us at The Historic Inns of Annapolis to host your Letter from upcoming event. Special occasions are worth celebrating and we think our Our Catering beautiful Historic venue is a great place Department to make history! We are delighted you are thinking of the MENU SELECTION Historic Inns of Annapolis to host your Please advise our Catering Department of your menu selections at your earliest convenience, but no later than three weeks prior special event. Celebrated occasions require to your scheduled function. The foregoing menu offerings are by focused attention to detail, impeccable no means a limit of our total capabilities. Our Catering Specialist welcomes the opportunity to submit additional menu proposals to timing, and food preparations that surpass suit your individual needs. everyone’s expectations. Flawless events are GUARANTEES what we do best… Overtime! A guarantee is required for all meal functions. Your Catering Executive must be notifi ed by 12:00 noon, three business days It begins with your Catering Specialist, prior to your event, of the exact number of guests you wish to guarantee. The Historic Inns will prepare for fi ve percent (5%) who organizes your menu selection with over your guarantee. In no case will the Historic Inns allow for a drop in guarantee numbers within this period to function. The bill our Executive Chef. They will take the necessary will be prepared for the guarantee number, or the actual number steps in the preparation and execution of your served, whichever is greater. In the event that the guarantee is not received by the above deadline, the original estimated attendance, event, coordinating the staff in perfect harmony, as indicated on the Banquet Event Order, would be billed. -

Cork City Attractions (Pdf)

12 Shandon Tower & Bells, 8 Crawford Art Gallery 9 Elizabeth Fort 10 The English Market 11 Nano Nagle Place St Anne’s Church 13 The Butter Museum 14 St Fin Barre’s Cathedral 15 St Peter’s Cork 16 Triskel Christchurch TOP ATTRACTIONS IN CORK C TY Crawford Art Gallery is a National Cultural Institution, housed in one of the most Cork City’s 17th century star-shaped fort, built in the aftermath of the Battle Trading as a market since 1788, it pre-dates most other markets of it’s kind. Nano Nagle Place is an historic oasis in the centre of bustling Cork city. The The red and white stone tower of St Anne’s Church Shandon, with its golden Located in the historic Shandon area, Cork’s unique museum explores the St. Fin Barre’s Cathedral is situated in the centre of Cork City. Designed by St Peter’s Cork situated in the heart of the Medieval town is the city’s oldest Explore and enjoy Cork’s Premier Arts and Culture Venue with its unique historic buildings in Cork City. Originally built in 1724, the building was transformed of Kinsale (1601) Elizabeth Fort served to reinforce English dominance and Indeed Barcelona’s famous Boqueria market did not start until 80 years after lovingly restored 18th century walled convent and contemplative gardens are salmon perched on top, is one of the city’s most iconic landmarks. One of the history and development of: William Burges and consecrated in 1870, the Cathedral lies on a site where church with parts of the building dating back to 12th century. -

A Taste of Ireland in Food and Pictures

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Cookery Books Publications 1994 A Taste of Ireland in Food and Pictures Theodora FitzGibbon Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/irckbooks Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation FitzGibbon, Theodora, "A Taste of Ireland in Food and Pictures" (1994). Cookery Books. 137. https://arrow.tudublin.ie/irckbooks/137 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cookery Books by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License A TASTE OF IRELAND IRISH TRADITIONAL FOOD BY THEODORA FITZGIBBON Period photographs specially prepared by George Morrison WEIDENFELD AND NICOLSON . LONDON For EDWARD MORRISON with affection © Estate of Theodora FitzGibbon, 1968 Foreword © Maeve Binchy, 1994 First published in 1968 First published in paperback in 1994 by George Weidenfeld and Nicolson Ltd Orion Publishing Group 5 Upper 5t Martin's Lane London WC2H 9EA All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise, without prior permission in writing of the copyright holder. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Printed and bound in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd, Frame and London ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank the friends who have helped me in my research, particularly Mrs A1ice Beary for the loan of eighteenth-century family manuscripts, and my aunt, Mrs Roberta Hodgins, Clonlara, Co. -

Food Tourism in Cork's English Market

Irish Business Journal Volume 10 Number 1 Article 6 1-1-2017 Food Tourism in Cork’s English Market - an Authentic Visitor Experience Lisa O'Riordan Prof. Margaret Linehan Cork Institute of Technology Aisling Ward Follow this and additional works at: https://sword.cit.ie/irishbusinessjournal Part of the Entrepreneurial and Small Business Operations Commons, Food and Beverage Management Commons, Food Studies Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Recommended Citation O'Riordan, Lisa; Linehan, Prof. Margaret; and Ward, Aisling (2017) "Food Tourism in Cork’s English Market - an Authentic Visitor Experience," Irish Business Journal: Vol. 10 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://sword.cit.ie/irishbusinessjournal/vol10/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Cork at SWORD - South West Open Research Deposit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Irish Business Journal by an authorized editor of SWORD - South West Open Research Deposit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Food Tourism in Cork’s English Market - an Authentic Visitor Experience Dr Lisa O’Riordan, Prof Margaret Linehan and Dr Aisling Ward Abstract Authenticity is deemed to be a crucial element in many tourism experiences. Tourism, however, is often accused of succumbing to notions of perceived authenticity to ensure commercial success, leading to misrepresentations of cultures. Food tourism, conversely, is advocated as a means of encountering genuine culture, history and lifestyle. This paper investigates the role of food tourism as an authentic representation of culture in Cork’s English Market. In-depth interviews were conducted with market traders and analysed through the grounded theory method.