Da Ponte in New York, Mozart in New York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musical Landmarks in New York

MUSICAL LANDMARKS IN NEW YORK By CESAR SAERCHINGER HE great war has stopped, or at least interrupted, the annual exodus of American music students and pilgrims to the shrines T of the muse. What years of agitation on the part of America- first boosters—agitation to keep our students at home and to earn recognition for our great cities as real centers of musical culture—have not succeeded in doing, this world catastrophe has brought about at a stroke, giving an extreme illustration of the proverb concerning the ill wind. Thus New York, for in- stance, has become a great musical center—one might even say the musical center of the world—for a majority of the world's greatest artists and teachers. Even a goodly proportion of its most eminent composers are gathered within its confines. Amer- ica as a whole has correspondingly advanced in rank among musical nations. Never before has native art received such serious attention. Our opera houses produce works by Americans as a matter of course; our concert artists find it popular to in- clude American compositions on their programs; our publishing houses publish new works by Americans as well as by foreigners who before the war would not have thought of choosing an Amer- ican publisher. In a word, America has taken the lead in mu- sical activity. What, then, is lacking? That we are going to retain this supremacy now that peace has come is not likely. But may we not look forward at least to taking our place beside the other great nations of the world, instead of relapsing into the status of a colony paying tribute to the mother country? Can not New York and Boston and Chicago become capitals in the empire of art instead of mere outposts? I am afraid that many of our students and musicians, for four years compelled to "make the best of it" in New York, are already looking eastward, preparing to set sail for Europe, in search of knowledge, inspiration and— atmosphere. -

In Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: the Image

Burlesquing “Otherness” 101 Burlesquing “Otherness” in Nineteenth-Century American Theatre: The Image of the Indian in John Brougham’s Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs (1847) and Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage (1855). Zoe Detsi-Diamanti When John Brougham’s Indian burlesque, Met-a-mora; or, The Last of the Pollywogs, opened in Boston at Brougham’s Adelphi Theatre on November 29, 1847, it won the lasting reputation of an exceptional satiric force in the American theatre for its author, while, at the same time, signaled the end of the serious Indian dramas that were so popular during the 1820s and 1830s. Eight years later, in 1855, Brougham made a most spectacular comeback with another Indian burlesque, Po-Ca-Hon-Tas; or, The Gentle Savage, an “Original, Aboriginal, Erratic, Operatic, Semi-Civilized, and Demi-savage Extravaganza,” which was produced at Wallack’s Lyceum Theatre in New York City.1 Both plays have been invariably cited as successful parodies of Augustus Stone’s Metamora; or, The Last of the Wampanoags (1829) and the stilted acting style of Edwin Forrest, and the Pocahontas plays of the first half of the nineteenth century. They are sig- nificant because they opened up new possibilities for the development of satiric comedy in America2 and substantially contributed to the transformation of the stage picture of the Indian from the romantic pattern of Arcadian innocence to a view far more satirical, even ridiculous. 0026-3079/2007/4803-101$2.50/0 American Studies, 48:3 (Fall 2007): 101-123 101 102 Zoe Detsi-Diamanti -

Italian-American Theatre

Saggi Italian-American Theatre Emelise Aleandri Artistic Director of «Frizzi & Lazzi», New York An Italian-American actor hesitates before the entrance to a shop in Little Italy at the turn of the century. It is a day in the life of a skilful, practiced ticket-vendor of the Italian-American theatre. To disguise the distress he feels at performing the onerous task that awaits him inside the shop, he assumes the mask of confidence, tinged slightly with arrogance. Summoning up a glib tongue, the actor enters the shop and before the shopkeeper knows what has happened, the actor fires away at him this familiar reprise: «Buongiorno. Come sta? La famiglia sta bene? Lei è un mecenate, lei è un benefattore del- la colonia. Io non so cosa faccia il governo italiano, dorme? Ma quando lo faremo cavaliere? Vuole un biglietto per una recita che si darà il mese en- trante: “La cieca di Sorrento?” Spettacoloso drama [sic]»1. With an unsuspecting shop owner, this spiel would almost always be suc- cessful in selling a ticket, but this one has been through this game before and when he learns that the performance is scheduled for a Thursday evening, he is quick to respond: «Oh! Guarda un po’, proprio giovedì che aspetto visite. Vi pare, con tutto il cuore!»2. But the actor is even quicker and has purpose- fully misinformed the storekeeper: «Mi sono sbagliato, è di venerdì»3. The shopkeeper, stunned, mumbles: «Oh! Venerdì... vedrò»4. Tricked, and now the reluctant buyer of a ticket, the shop owner spits back «Come siete seccanti voi altri teatristi!»5. -

19Th Century Playbills, 1803-1902 FLP.THC.PLAYBILLS Finding Aid Prepared by Megan Good and Forrest Wright

19th Century playbills, 1803-1902 FLP.THC.PLAYBILLS Finding aid prepared by Megan Good and Forrest Wright This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit November 08, 2011 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Free Library of Philadelphia: Rare Book Department 2010.06.22 Philadelphia, PA, 19103 19th Century playbills, 1803-1902 FLP.THC.PLAYBILLS Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 5 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 5 Arrangement note...........................................................................................................................................6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................6 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory..................................................................................................................................... -

The Extraordinary Lives of Lorenzo Da Ponte & Nathaniel Wallich

C O N N E C T I N G P E O P L E , P L A C E S , A N D I D E A S : S T O R Y B Y S T O R Y J ULY 2 0 1 3 ABOUT WRR CONTRIBUTORS MISSION SPONSORSHIP MEDIA KIT CONTACT DONATE Search Join our mailing list and receive Email Print More WRR Monthly. Wild River Consulting ESSAY-The Extraordinary Lives of Lorenzo Da Ponte & Nathaniel & Wallich : Publishing Click below to make a tax- deductible contribution. Religious Identity in the Age of Enlightenment where Your literary b y J u d i t h M . T a y l o r , J u l e s J a n i c k success is our bottom line. PEOPLE "By the time the Interv iews wise woman has found a bridge, Columns the crazy woman has crossed the Blogs water." PLACES Princeton The United States The World Open Borders Lorenzo Da Ponte Nathaniel Wallich ANATOLIAN IDEAS DAYS & NIGHTS Being Jewish in a Christian world has always been fraught with difficulties. The oppression of the published by Art, Photography and Wild River Books Architecture Jews in Europe for most of the last two millennia was sanctioned by law and without redress. Valued less than cattle, herded into small enclosed districts, restricted from owning land or entering any Health, Culture and Food profession, and subject to random violence and expulsion at any time, the majority of Jews lived a History , Religion and Reserve Your harsh life.1 The Nazis used this ancient technique of de-humanization and humiliation before they hit Philosophy Wild River Ad on the idea of expunging the Jews altogether. -

Overture to Don Giovanni, K. 527—Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Overture to Don Giovanni, K. 527—Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Mozart’s incomparable musical gifts enabled him to compose at the highest level of artistic brilliance in almost every musical genre. We are privileged to experience his legacy in symphonies, chamber music, wind serenades, choral music, keyboard music—the list goes on and on. But, unquestionably, his greatest contributions to musical art are his operas. No one— not even Wagner, Verdi, Puccini, or Richard Strauss exceeded the perfection of Mozart’s mature operas. The reason, of course, is clear: his unparalleled musical gift is served and informed by a nuanced insight into human psychology that is simply stunning. His characters represented real men and women on the stage, who moved dramatically, and who had distinctive personalities. Of no opera is this truer than his foray into serious opera in the Italian style, Don Giovanni. Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, at its première in Vienna in 1786, was a decided success, but nothing like the acclaim that it garnered later, in December of that same year, in Prague. The city literally went wild for it, bringing the composer to the Bohemian capital to conduct performances in January of 1787. A commission for another hit ensued, and Mozart once again collaborated with librettist, Lorenzo Da Ponte—this time basing the opera on the legendary seducer, Don Juan. Italian opera buffa is comic opera, and Mozart was a master of it, but the new opera—given the theme—is a serious one, with hilarious, comic interludes. Shakespeare often made adroit use of the dramatic contrast in that ploy, and so does Mozart, with equal success. -

Antonio Salieri's Revenge

Antonio Salieri’s Revenge newyorker.com/magazine/2019/06/03/antonio-salieris-revenge By Alex Ross 1/13 Many composers are megalomaniacs or misanthropes. Salieri was neither. Illustration by Agostino Iacurci On a chilly, wet day in late November, I visited the Central Cemetery, in Vienna, where 2/13 several of the most familiar figures in musical history lie buried. In a musicians’ grove at the heart of the complex, Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms rest in close proximity, with a monument to Mozart standing nearby. According to statistics compiled by the Web site Bachtrack, works by those four gentlemen appear in roughly a third of concerts presented around the world in a typical year. Beethoven, whose two-hundred-and-fiftieth birthday arrives next year, will supply a fifth of Carnegie Hall’s 2019-20 season. When I entered the cemetery, I turned left, disregarding Beethoven and company. Along the perimeter wall, I passed an array of lesser-known but not uninteresting figures: Simon Sechter, who gave a counterpoint lesson to Schubert; Theodor Puschmann, an alienist best remembered for having accused Wagner of being an erotomaniac; Carl Czerny, the composer of piano exercises that have tortured generations of students; and Eusebius Mandyczewski, a magnificently named colleague of Brahms. Amid these miscellaneous worthies, resting beneath a noble but unpretentious obelisk, is the composer Antonio Salieri, Kapellmeister to the emperor of Austria. I had brought a rose, thinking that the grave might be a neglected and cheerless place. Salieri is one of history’s all-time losers—a bystander run over by a Mack truck of malicious gossip. -

Anathema of Venice: Lorenzo Da Ponte, Mozart's

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 33, Number 46, November 17, 2006 EIRFeature ANATHEMA OF VENICE Lorenzo Da Ponte: Mozart’s ‘American’ Librettist by Susan W. Bowen and made a revolution in opera, who was kicked out of Venice by the Inquisition because of his ideas, who, emigrating to The Librettist of Venice; The Remarkable America where he introduced the works of Dante Alighieri Life of Lorenzo Da Ponte; Mozart’s Poet, and Italian opera, and found himself among the circles of the Casanova’s Friend, and Italian Opera’s American System thinkers in Philadelphia and New York, Impresario in America was “not political”? It became obvious that the glaring omis- by Rodney Bolt Edinburgh, U.K.: Bloomsbury, 2006 sion in Rodney Bolt’s book is the “American hypothesis.” 428 pages, hardbound, $29.95 Any truly authentic biography of this Classi- cal scholar, arch-enemy of sophistry, and inde- As the 250th anniversary of the birth of Wolfgang Amadeus fatigable promoter of Mozart approached, I was happy to see the appearance of this creativity in science and new biography of Lorenzo Da Ponte, librettist for Mozart’s art, must needs bring to three famous operas against the European oligarchy, Mar- light that truth which riage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Cosi fan tutte. The story Venice, even today, of the life of Lorenzo Da Ponte has been entertaining students would wish to suppress: of Italian for two centuries, from his humble roots in the that Lorenzo Da Ponte, Jewish ghetto, beginning in 1749, through his days as a semi- (1749-1838), like Mo- nary student and vice rector and priest, Venetian lover and zart, (1756-91), was a gambler, poet at the Vienna Court of Emperor Joseph II, product of, and also a through his crowning achievement as Mozart’s collaborator champion of the Ameri- in revolutionizing opera; to bookseller, printer, merchant, de- can Revolution and the voted husband, and librettist in London in the 1790s, with Renaissance idea of man stops along the way in Padua, Trieste, Brussels, Holland, Flor- that it represented. -

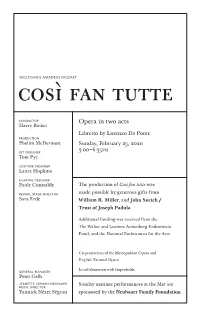

02-23-2020 Cosi Fan Tutte Mat.Indd

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART così fan tutte conductor Opera in two acts Harry Bicket Libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte production Phelim McDermott Sunday, February 23, 2020 PM set designer 3:00–6:35 Tom Pye costume designer Laura Hopkins lighting designer Paule Constable The production of Così fan tutte was revival stage director made possible by generous gifts from Sara Erde William R. Miller, and John Sucich / Trust of Joseph Padula Additional funding was received from the The Walter and Leonore Annenberg Endowment Fund, and the National Endowment for the Arts Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera and English National Opera In collaboration with Improbable general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer Sunday matinee performances at the Met are music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 202nd Metropolitan Opera performance of WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART’S così fan tutte conductor Harry Bicket in order of vocal appearance ferrando skills ensemble Ben Bliss* Leo the Human Gumby Jonathan Nosan guglielmo Ray Valenz Luca Pisaroni Josh Walker Betty Bloomerz don alfonso Anna Venizelos Gerald Finley Zoe Ziegfeld Cristina Pitter fiordiligi Sarah Folkins Nicole Car Sage Sovereign Arthur Lazalde dorabella Radu Spinghel Serena Malfi despina continuo Heidi Stober harpsichord Jonathan C. Kelly cello David Heiss Sunday, February 23, 2020, 3:00–6:35PM RICHARD TERMINE / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Mozart’s Così Musical Preparation Joel Revzen, Liora Maurer, fan tutte and Jonathan -

Broadway Theatre

Broadway theatre This article is about the type of theatre called “Broad- The Broadway Theater District is a popular tourist at- way”. For the street for which it is named, see Broadway traction in New York City. According to The Broadway (Manhattan). League, Broadway shows sold a record US$1.36 billion For the individual theatre of this name, see Broadway worth of tickets in 2014, an increase of 14% over the pre- Theatre (53rd Street). vious year. Attendance in 2014 stood at 13.13 million, a 13% increase over 2013.[2] Coordinates: 40°45′21″N 73°59′11″W / 40.75583°N The great majority of Broadway shows are musicals. His- 73.98639°W torian Martin Shefter argues, "'Broadway musicals,' cul- minating in the productions of Richard Rodgers and Os- car Hammerstein, became enormously influential forms of American popular culture” and helped make New York City the cultural capital of the nation.[3] 1 History 1.1 Early theatre in New York Interior of the Park Theatre, built in 1798 New York did not have a significant theatre presence un- til about 1750, when actor-managers Walter Murray and Thomas Kean established a resident theatre company at the Theatre on Nassau Street, which held about 280 peo- ple. They presented Shakespeare plays and ballad op- eras such as The Beggar’s Opera.[4] In 1752, William The Lion King at the New Amsterdam Theatre in 2003, in the Hallam sent a company of twelve actors from Britain background is Madame Tussauds New York to the colonies with his brother Lewis as their manager. -

A C AHAH C (Key of a Major, German Designation) a Ballynure Ballad C a Ballynure Ballad C (A) Bal-Lih-N'yôôr BAL-Ludd a Capp

A C AHAH C (key of A major, German designation) A ballynure ballad C A Ballynure Ballad C (A) bal-lih-n’YÔÔR BAL-ludd A cappella C {ah kahp-PELL-luh} ah kahp-PAYL-lah A casa a casa amici C A casa, a casa, amici C ah KAH-zah, ah KAH-zah, ah-MEE-chee C (excerpt from the opera Cavalleria rusticana [kah-vahl-lay-REE-ah roo-stee-KAH-nah] — Rustic Chivalry; music by Pietro Mascagni [peeAY-tro mah-SKAH-n’yee]; libretto by Guido Menasci [gooEE-doh may-NAH-shee] and Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti [jo-VAHN-nee tar-JO- nee-toht-TSAYT-tee] after Giovanni Verga [jo-VAHN-nee VAYR-gah]) A casinha pequeninaC ah kah-ZEE-n’yuh peh-keh-NEE-nuh C (A Tiny House) C (song by Francisco Ernani Braga [frah6-SEESS-kôô ehr-NAH-nee BRAH-guh]) A chantar mer C A chantar m’er C ah shah6-tar mehr C (12th-century composition by Beatriz de Dia [bay-ah-treess duh dee-ah]) A chloris C A Chloris C ah klaw-reess C (To Chloris) C (poem by Théophile de Viau [tay- aw-feel duh veeo] set to music by Reynaldo Hahn [ray-NAHL-doh HAHN]) A deux danseuses C ah dö dah6-söz C (poem by Voltaire [vawl-tehr] set to music by Jacques Chailley [zhack shahee-yee]) A dur C A Dur C AHAH DOOR C (key of A major, German designation) A finisca e per sempre C ah fee-NEE-skah ay payr SAYM-pray C (excerpt from the opera Orfeo ed Euridice [ohr-FAY-o ayd ayoo-ree-DEE-chay]; music by Christoph Willibald von Gluck [KRIH-stawf VILL-lee-bahlt fawn GLÔÔK] and libretto by Ranieri de’ Calzabigi [rah- neeAY-ree day kahl-tsah-BEE-jee]) A globo veteri C AH GLO-bo vay-TAY-ree C (When from primeval mass) C (excerpt from -

Rooting out Historical Mythologies; William Dunlap's a Trip to Niagara and Its Sophisticated Nineteenth Century Audience

Global Posts building CUNY Communities since 2009 http://tags.commons.gc.cuny.edu Rooting Out Historical Mythologies; William Dunlap’s A Trip to Niagara and its Sophisticated Nineteenth Century Audience. William Dunlap’s final play, A Trip to Niagara (1828), might be the most misunderstood play in the history of the American stage. Despite being an unqualified success with its cosmopolitan New York audiences in 1828-9, it has been regularly, and almost always inaccurately, maligned by twentieth and twenty-first century historians who have described the play as a “well-done hackwork;” full of “puerile scenes and irrelevant characters;” and valuable only for the “certain amount of low comedy” that “could be extracted from it.” [1] At best Dunlap’s play has been described as “a workmanlike job;” at worst, “one of his poorest” efforts, a play that “could hardly be said to have challenged the preeminence of contemporary British playwrights, let alone Shakespeare.”[2] As I will argue in this essay, the glaring disconnect between the play’s warm public reception and its subsequent criticism by historians often appears to be rooted in a kind of historical mythology that haunts the field of theatre history. Unperceived biases and assumptions often color interpretations of historical evidence, and these flawed perceptions are frequently transmitted from one generation of historians to the next, forming a kind of mythology around a subject that has the power to color future interpretations of new evidence. Just such a historical mythology appears to be at the heart of most criticisms of A Trip to Niagara.