Italian-American Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musical Landmarks in New York

MUSICAL LANDMARKS IN NEW YORK By CESAR SAERCHINGER HE great war has stopped, or at least interrupted, the annual exodus of American music students and pilgrims to the shrines T of the muse. What years of agitation on the part of America- first boosters—agitation to keep our students at home and to earn recognition for our great cities as real centers of musical culture—have not succeeded in doing, this world catastrophe has brought about at a stroke, giving an extreme illustration of the proverb concerning the ill wind. Thus New York, for in- stance, has become a great musical center—one might even say the musical center of the world—for a majority of the world's greatest artists and teachers. Even a goodly proportion of its most eminent composers are gathered within its confines. Amer- ica as a whole has correspondingly advanced in rank among musical nations. Never before has native art received such serious attention. Our opera houses produce works by Americans as a matter of course; our concert artists find it popular to in- clude American compositions on their programs; our publishing houses publish new works by Americans as well as by foreigners who before the war would not have thought of choosing an Amer- ican publisher. In a word, America has taken the lead in mu- sical activity. What, then, is lacking? That we are going to retain this supremacy now that peace has come is not likely. But may we not look forward at least to taking our place beside the other great nations of the world, instead of relapsing into the status of a colony paying tribute to the mother country? Can not New York and Boston and Chicago become capitals in the empire of art instead of mere outposts? I am afraid that many of our students and musicians, for four years compelled to "make the best of it" in New York, are already looking eastward, preparing to set sail for Europe, in search of knowledge, inspiration and— atmosphere. -

The Role of Literature in the Films of Luchino Visconti

From Page to Screen: the Role of Literature in the Films of Luchino Visconti Lucia Di Rosa A thesis submitted in confomity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph. D.) Graduate Department of ltalian Studies University of Toronto @ Copyright by Lucia Di Rosa 2001 National Library Biblioth ue nationale du Cana2 a AcquisitTons and Acquisitions ef Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 WeOingtOn Street 305, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Otiawa ON K1AW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence ailowing the exclusive ~~mnettantà la Natiofliil Library of Canarla to Bibliothèque nation& du Canada de reprcduce, loan, disûi'bute or seil reproduire, prêter, dishibuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicroform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format é1ectronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation, From Page to Screen: the Role of Literatuce in the Films af Luchino Vionti By Lucia Di Rosa Ph.D., 2001 Department of Mian Studies University of Toronto Abstract This dissertation focuses on the role that literature plays in the cinema of Luchino Visconti. The Milanese director baseci nine of his fourteen feature films on literary works. -

The Extraordinary Lives of Lorenzo Da Ponte & Nathaniel Wallich

C O N N E C T I N G P E O P L E , P L A C E S , A N D I D E A S : S T O R Y B Y S T O R Y J ULY 2 0 1 3 ABOUT WRR CONTRIBUTORS MISSION SPONSORSHIP MEDIA KIT CONTACT DONATE Search Join our mailing list and receive Email Print More WRR Monthly. Wild River Consulting ESSAY-The Extraordinary Lives of Lorenzo Da Ponte & Nathaniel & Wallich : Publishing Click below to make a tax- deductible contribution. Religious Identity in the Age of Enlightenment where Your literary b y J u d i t h M . T a y l o r , J u l e s J a n i c k success is our bottom line. PEOPLE "By the time the Interv iews wise woman has found a bridge, Columns the crazy woman has crossed the Blogs water." PLACES Princeton The United States The World Open Borders Lorenzo Da Ponte Nathaniel Wallich ANATOLIAN IDEAS DAYS & NIGHTS Being Jewish in a Christian world has always been fraught with difficulties. The oppression of the published by Art, Photography and Wild River Books Architecture Jews in Europe for most of the last two millennia was sanctioned by law and without redress. Valued less than cattle, herded into small enclosed districts, restricted from owning land or entering any Health, Culture and Food profession, and subject to random violence and expulsion at any time, the majority of Jews lived a History , Religion and Reserve Your harsh life.1 The Nazis used this ancient technique of de-humanization and humiliation before they hit Philosophy Wild River Ad on the idea of expunging the Jews altogether. -

Overture to Don Giovanni, K. 527—Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Overture to Don Giovanni, K. 527—Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Mozart’s incomparable musical gifts enabled him to compose at the highest level of artistic brilliance in almost every musical genre. We are privileged to experience his legacy in symphonies, chamber music, wind serenades, choral music, keyboard music—the list goes on and on. But, unquestionably, his greatest contributions to musical art are his operas. No one— not even Wagner, Verdi, Puccini, or Richard Strauss exceeded the perfection of Mozart’s mature operas. The reason, of course, is clear: his unparalleled musical gift is served and informed by a nuanced insight into human psychology that is simply stunning. His characters represented real men and women on the stage, who moved dramatically, and who had distinctive personalities. Of no opera is this truer than his foray into serious opera in the Italian style, Don Giovanni. Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, at its première in Vienna in 1786, was a decided success, but nothing like the acclaim that it garnered later, in December of that same year, in Prague. The city literally went wild for it, bringing the composer to the Bohemian capital to conduct performances in January of 1787. A commission for another hit ensued, and Mozart once again collaborated with librettist, Lorenzo Da Ponte—this time basing the opera on the legendary seducer, Don Juan. Italian opera buffa is comic opera, and Mozart was a master of it, but the new opera—given the theme—is a serious one, with hilarious, comic interludes. Shakespeare often made adroit use of the dramatic contrast in that ploy, and so does Mozart, with equal success. -

CONTEMPORARY PROXIMITY FICTION. GUEST EDITED by NADIA ALONSO VOLUME IV, No 01 · SPRING 2018

CONTEMPORARY PROXIMITY FICTION. GUEST EDITED BY NADIA ALONSO VOLUME IV, No 01 · SPRING 2018 PUBLISHED WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF EDITORS ABIS – AlmaDL, Università di Bologna Veronica Innocenti, Héctor J. Pérez and Guglielmo Pescatore. E-MAIL ADDRESS ASSOCIATE EDITOR [email protected] Elliott Logan HOMEPAGE GUEST EDITORS series.unibo.it Nadia Alonso ISSN SECRETARIES 2421-454X Luca Barra, Paolo Noto. DOI EDITORIAL BOARD https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2421-454X/v4-n1-2018 Marta Boni, Université de Montréal (Canada), Concepción Cascajosa, Universidad Carlos III (Spain), Fernando Canet Centellas, Universitat Politècnica de València (Spain), Alexander Dhoest, Universiteit Antwerpen (Belgium), Julie Gueguen, Paris 3 (France), Lothar Mikos, Hochschule für Film und Fernsehen “Konrad Wolf” in Potsdam- Babelsberg (Germany), Jason Mittell, Middlebury College (USA), Roberta Pearson, University of Nottingham (UK), Xavier Pérez Torio, Universitat Pompeu Fabra (Spain), Veneza Ronsini, Universidade SERIES has two main purposes: first, to respond to the surge Federal de Santa María (Brasil), Massimo Scaglioni, Università Cattolica di Milano (Italy), Murray Smith, University of Kent (UK). of scholarly interest in TV series in the past few years, and compensate for the lack of international journals special- SCIENTIFIC COMMITEE izing in TV seriality; and second, to focus on TV seriality Gunhild Agger, Aalborg Universitet (Denmark), Sarah Cardwell, through the involvement of scholars and readers from both University of Kent (UK), Sonja de Leeuw, Universiteit Utrecht (Netherlands), Sergio Dias Branco, Universidade de Coimbra the English-speaking world and the Mediterranean and Latin (Portugal), Elizabeth Evans, University of Nottingham (UK), Aldo American regions. This is the reason why the journal’s official Grasso, Università Cattolica di Milano (Italy), Sarah Hatchuel, languages are Italian, Spanish and English. -

Antonio Salieri's Revenge

Antonio Salieri’s Revenge newyorker.com/magazine/2019/06/03/antonio-salieris-revenge By Alex Ross 1/13 Many composers are megalomaniacs or misanthropes. Salieri was neither. Illustration by Agostino Iacurci On a chilly, wet day in late November, I visited the Central Cemetery, in Vienna, where 2/13 several of the most familiar figures in musical history lie buried. In a musicians’ grove at the heart of the complex, Beethoven, Schubert, and Brahms rest in close proximity, with a monument to Mozart standing nearby. According to statistics compiled by the Web site Bachtrack, works by those four gentlemen appear in roughly a third of concerts presented around the world in a typical year. Beethoven, whose two-hundred-and-fiftieth birthday arrives next year, will supply a fifth of Carnegie Hall’s 2019-20 season. When I entered the cemetery, I turned left, disregarding Beethoven and company. Along the perimeter wall, I passed an array of lesser-known but not uninteresting figures: Simon Sechter, who gave a counterpoint lesson to Schubert; Theodor Puschmann, an alienist best remembered for having accused Wagner of being an erotomaniac; Carl Czerny, the composer of piano exercises that have tortured generations of students; and Eusebius Mandyczewski, a magnificently named colleague of Brahms. Amid these miscellaneous worthies, resting beneath a noble but unpretentious obelisk, is the composer Antonio Salieri, Kapellmeister to the emperor of Austria. I had brought a rose, thinking that the grave might be a neglected and cheerless place. Salieri is one of history’s all-time losers—a bystander run over by a Mack truck of malicious gossip. -

Il Teatro Significa Vivere Sul Serio Quello Che Gli Altri Nella Vita Recitano Male.”1

1 Introduction “Il teatro significa vivere sul serio quello che gli altri nella vita recitano male.”1 Many years ago a young boy sat with his friend, the son of a lawyer, in the Corte Minorile of Naples, watching as petty criminals about his age were being judged for their offenses. One ragged pick-pocket who had been found guilty demanded to be led away after being sentenced; instead he was left there and his loud pleas were completely disregarded. Unwilling to tolerate this final offense of being treated as though he were invisible, the juvenile delinquent, in an extreme act of rebellion, began smashing the chains around his hands against his own head until his face was a mask of blood. Horrified, the judge finally ordered everybody out of the court. That young boy sitting in court watching the gruesome scene was Eduardo De Filippo and the sense of helplessness and social injustice witnessed left an indelible mark on the impressionable mind of the future playwright. Almost sixty years later, at the Accademia dei Lincei, as he accepted the Premio Internazionale Feltrinelli, one of Italy’s highest literary accolades, De Filippo recalled how it was that this early image of the individual pitted against society was always at the basis of his work: Alla base del mio teatro c’è sempre il conflitto fra individuo e società […] tutto ha inizio, sempre, da uno stimolo emotivo: reazione a un’ingiustizia, sdegno per l’ipocrisia mia e altrui, solidarietà e simpatia umana per una persona o un gruppo di persone, ribellione contro leggi superate e anacronistiche con il mondo di oggi, sgomento di fronte a fatti che, come le guerre, sconvolgono la vita dei popoli.2 The purpose of this thesis is twofold: to provide for the first time a translation of Eduardo’s last play, Gli esami non finiscono mai (Exams Never End), and to trace the development of his dramatic style and philosophy in order to appreciate their culmination 1 Enzo Biagi, “Eduardo, tragico anche se ride,” Corriere della Sera , 6 March 1977. -

Nemla Italian Studies

Nemla Italian Studies Journal of Italian Studies Italian Section Northeast Modern Language Association Editor: Simona Wright The College of New Jersey Volume xxxi, 20072008 i Nemla Italian Studies (ISSN 10876715) Is a refereed journal published by the Italian section of the Northeast Modern Language Association under the sponsorship of NeMLA and The College of New Jersey Department of Modern Languages 2000 Pennington Road Ewing, NJ 086280718 It contains a section of articles submitted by NeMLA members and Italian scholars and a section of book reviews. Participation is open to those who qualify under the general NeMLA regulations and comply with the guidelines established by the editors of NeMLA Italian Studies Essays appearing in this journal are listed in the PMLA and Italica. Each issue of the journal is listed in PMLA Directory of Periodicals, Ulrich International Periodicals Directory, Interdok Directory of Public Proceedings, I.S.I. Index to Social Sciences and Humanities Proceedings. Subscription is obtained by placing a standing order with the editor at the above The College of New Jersey address: each new or back issue is billed $5 at mailing. ********************* ii Editorial Board for This Volume Founder: Joseph Germano, Buffalo State University Editor: Simona Wright, The College of New Jersey Associate Editor: Umberto Mariani, Rutgers University Assistant to the Editor as Referees: Umberto Mariani, Rugers University Federica Anichini, The College of New Jersey Daniela Antonucci, Princeton University Eugenio Bolongaro, McGill University Marco Cerocchi, Lasalle University Francesco Ciabattoni, Dalhousie University Giuseppina Mecchia, University of Pittsburgh Maryann Tebben, Simons Rock University MLA Style Consultants: Framcesco Ciabattoni, Dalhousie University Chiara Frenquellucci, Harvard University iii Volume xxxi 20072008 CONTENTS Acrobati senza rete: lavoro e identità maschile nel cinema di G. -

Anathema of Venice: Lorenzo Da Ponte, Mozart's

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 33, Number 46, November 17, 2006 EIRFeature ANATHEMA OF VENICE Lorenzo Da Ponte: Mozart’s ‘American’ Librettist by Susan W. Bowen and made a revolution in opera, who was kicked out of Venice by the Inquisition because of his ideas, who, emigrating to The Librettist of Venice; The Remarkable America where he introduced the works of Dante Alighieri Life of Lorenzo Da Ponte; Mozart’s Poet, and Italian opera, and found himself among the circles of the Casanova’s Friend, and Italian Opera’s American System thinkers in Philadelphia and New York, Impresario in America was “not political”? It became obvious that the glaring omis- by Rodney Bolt Edinburgh, U.K.: Bloomsbury, 2006 sion in Rodney Bolt’s book is the “American hypothesis.” 428 pages, hardbound, $29.95 Any truly authentic biography of this Classi- cal scholar, arch-enemy of sophistry, and inde- As the 250th anniversary of the birth of Wolfgang Amadeus fatigable promoter of Mozart approached, I was happy to see the appearance of this creativity in science and new biography of Lorenzo Da Ponte, librettist for Mozart’s art, must needs bring to three famous operas against the European oligarchy, Mar- light that truth which riage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Cosi fan tutte. The story Venice, even today, of the life of Lorenzo Da Ponte has been entertaining students would wish to suppress: of Italian for two centuries, from his humble roots in the that Lorenzo Da Ponte, Jewish ghetto, beginning in 1749, through his days as a semi- (1749-1838), like Mo- nary student and vice rector and priest, Venetian lover and zart, (1756-91), was a gambler, poet at the Vienna Court of Emperor Joseph II, product of, and also a through his crowning achievement as Mozart’s collaborator champion of the Ameri- in revolutionizing opera; to bookseller, printer, merchant, de- can Revolution and the voted husband, and librettist in London in the 1790s, with Renaissance idea of man stops along the way in Padua, Trieste, Brussels, Holland, Flor- that it represented. -

Enrico Caruso and Eduardo Migliaccio

Differentia: Review of Italian Thought Number 6 Combined Issue 6-7 Spring/Autumn Article 15 1994 Performing High, Performing Low: Enrico Caruso and Eduardo Migliaccio Esther Romeyn Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia Recommended Citation Romeyn, Esther (1994) "Performing High, Performing Low: Enrico Caruso and Eduardo Migliaccio," Differentia: Review of Italian Thought: Vol. 6 , Article 15. Available at: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia/vol6/iss1/15 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Academic Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Differentia: Review of Italian Thought by an authorized editor of Academic Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Performing High, Performing Low: Enrico Caruso and Eduardo Migliaccio Esther Romeyn It is an evening during World War I. In a little theater on Mulberry Street, the heart of New York's Little Italy, the public awaits the appearance of the Italian American clown Eduardo Migliaccio, better known under his stage name "Farfariello," who will perform in a tribute to the Italian war effort. The evening, according to the journalist covering the festivities, "promises to be an enormous success, not only on the artistic level, but also as an affirmation of Italianness." 1 With a sense of pathos appropriate to the occasion, his account portrays the unfolding of events: It was an evening in honor of Farfariello, an evening benefitting the Italian patriotic cause. In a box in the front, Enrico Caruso was present as well. The stage was all adorned with Italian flags. -

02-23-2020 Cosi Fan Tutte Mat.Indd

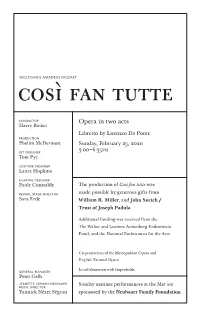

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART così fan tutte conductor Opera in two acts Harry Bicket Libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte production Phelim McDermott Sunday, February 23, 2020 PM set designer 3:00–6:35 Tom Pye costume designer Laura Hopkins lighting designer Paule Constable The production of Così fan tutte was revival stage director made possible by generous gifts from Sara Erde William R. Miller, and John Sucich / Trust of Joseph Padula Additional funding was received from the The Walter and Leonore Annenberg Endowment Fund, and the National Endowment for the Arts Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera and English National Opera In collaboration with Improbable general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer Sunday matinee performances at the Met are music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 202nd Metropolitan Opera performance of WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART’S così fan tutte conductor Harry Bicket in order of vocal appearance ferrando skills ensemble Ben Bliss* Leo the Human Gumby Jonathan Nosan guglielmo Ray Valenz Luca Pisaroni Josh Walker Betty Bloomerz don alfonso Anna Venizelos Gerald Finley Zoe Ziegfeld Cristina Pitter fiordiligi Sarah Folkins Nicole Car Sage Sovereign Arthur Lazalde dorabella Radu Spinghel Serena Malfi despina continuo Heidi Stober harpsichord Jonathan C. Kelly cello David Heiss Sunday, February 23, 2020, 3:00–6:35PM RICHARD TERMINE / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Mozart’s Così Musical Preparation Joel Revzen, Liora Maurer, fan tutte and Jonathan -

A C AHAH C (Key of a Major, German Designation) a Ballynure Ballad C a Ballynure Ballad C (A) Bal-Lih-N'yôôr BAL-Ludd a Capp

A C AHAH C (key of A major, German designation) A ballynure ballad C A Ballynure Ballad C (A) bal-lih-n’YÔÔR BAL-ludd A cappella C {ah kahp-PELL-luh} ah kahp-PAYL-lah A casa a casa amici C A casa, a casa, amici C ah KAH-zah, ah KAH-zah, ah-MEE-chee C (excerpt from the opera Cavalleria rusticana [kah-vahl-lay-REE-ah roo-stee-KAH-nah] — Rustic Chivalry; music by Pietro Mascagni [peeAY-tro mah-SKAH-n’yee]; libretto by Guido Menasci [gooEE-doh may-NAH-shee] and Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti [jo-VAHN-nee tar-JO- nee-toht-TSAYT-tee] after Giovanni Verga [jo-VAHN-nee VAYR-gah]) A casinha pequeninaC ah kah-ZEE-n’yuh peh-keh-NEE-nuh C (A Tiny House) C (song by Francisco Ernani Braga [frah6-SEESS-kôô ehr-NAH-nee BRAH-guh]) A chantar mer C A chantar m’er C ah shah6-tar mehr C (12th-century composition by Beatriz de Dia [bay-ah-treess duh dee-ah]) A chloris C A Chloris C ah klaw-reess C (To Chloris) C (poem by Théophile de Viau [tay- aw-feel duh veeo] set to music by Reynaldo Hahn [ray-NAHL-doh HAHN]) A deux danseuses C ah dö dah6-söz C (poem by Voltaire [vawl-tehr] set to music by Jacques Chailley [zhack shahee-yee]) A dur C A Dur C AHAH DOOR C (key of A major, German designation) A finisca e per sempre C ah fee-NEE-skah ay payr SAYM-pray C (excerpt from the opera Orfeo ed Euridice [ohr-FAY-o ayd ayoo-ree-DEE-chay]; music by Christoph Willibald von Gluck [KRIH-stawf VILL-lee-bahlt fawn GLÔÔK] and libretto by Ranieri de’ Calzabigi [rah- neeAY-ree day kahl-tsah-BEE-jee]) A globo veteri C AH GLO-bo vay-TAY-ree C (When from primeval mass) C (excerpt from