THE ELIZABETHAN IDEA of EMPIRE by David Armitage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Justice in an Open World – the Role Of

E c o n o m i c & Social Affairs The International Forum for Social Development Social Justice in an Open World The Role of the United Nations Sales No. E.06.IV.2 ISBN 92-1-130249-5 05-62917—January 2006—2,000 United Nations ST/ESA/305 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS Division for Social Policy and Development The International Forum for Social Development Social Justice in an Open World The Role of the United Nations asdf United Nations New York, 2006 DESA The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environ- mental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint course of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises inter- ested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks devel- oped in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. Note The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of the mate- rial do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitations of its frontiers. -

The Cultural and Ideological Significance of Representations of Boudica During the Reigns of Elizabeth I and James I

EXETER UNIVERSITY AND UNIVERSITÉ D’ORLÉANS The Cultural and Ideological Significance Of Representations of Boudica During the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I. Submitted by Samantha FRENEE-HUTCHINS to the universities of Exeter and Orléans as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, June 2009. This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ..................................... (signature) 2 Abstract in English: This study follows the trail of Boudica from her rediscovery in Classical texts by the humanist scholars of the fifteenth century to her didactic and nationalist representations by Italian, English, Welsh and Scottish historians such as Polydore Virgil, Hector Boece, Humphrey Llwyd, Raphael Holinshed, John Stow, William Camden, John Speed and Edmund Bolton. In the literary domain her story was appropriated under Elizabeth I and James I by poets and playwrights who included James Aske, Edmund Spenser, Ben Jonson, William Shakespeare, A. Gent and John Fletcher. As a political, religious and military figure in the middle of the first century AD this Celtic and regional queen of Norfolk is placed at the beginning of British history. In a gesture of revenge and despair she had united a great number of British tribes and opposed the Roman Empire in a tragic effort to obtain liberty for her family and her people. -

Detachment Instead of Confrontation: Post-European Russia in Search of Self-Sufficiency

Detachment Instead of Confrontation: Post-European Russia in Search of Self-Sufficiency Alexei Miller, Fyodor Lukyanov The report was written by Alexei Miller, Professor at European University in St. Petersburg and Central European University in Budapest; Fyodor lukyAnov, Editor-in-Chief of the Russia in Global Affairs magazine and a Research Professor at the National Research University-Higher School of Economics. Alexei Miller, Fyodor Lukyanov Along with all the complexes of a superior nation, Russia has the great inferiority complex of a small country. Joseph Brodsky Less Than One, 1976 “Our eagle, the heritage of Byzantium, is a two-headed one. Of course, eagles with one head are strong and powerful as well, but if you cut off the head of our eagle which is turned to the East, you will not turn him into a one-headed eagle, you will only make him bleed.” Russian Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin, from the speech in the State Duma in support of the construction of the Amur Railway, 1908 This project originated in 2015 when intellectual interaction between Russia and the West was rapidly degrading to mutual accusations and verbal fights over “who is to blame” and “how much more Russia should suffer before it is ready to repent.” We sought to provide a forum for analysts and political practitioners from Russia, Europe, the United States, and China to con- duct a constructive dialogue and ultimately move from producing endless recriminations and claims to discussing the future of Russia’s role in international affairs. Naturally, this also meant discussing the future of the world as a whole. -

Writing Another Continent's History: the British and Pre-Colonial Africa

eSharp Historical Perspectives Writing Another Continent’s History: The British and Pre-colonial Africa, 1880-1939 Christopher Prior (Durham University) Tales of Britons striding purposefully through the jungles and across the arid deserts of Africa captivated the metropolitan reading public throughout the nineteenth century. This interest only increased with time, and by the last quarter of the century a corpus of heroes both real and fictional, be they missionaries, explorers, traders, or early officials, was formalized (for example, see Johnson, 1982). While, for instance, the travel narratives of Burton, Speke, and other famous Victorians remained perennially popular, a greater number of works that emerged following the ‘Scramble for Africa’ began to put such endeavours into wider historical context. In contrast to the sustained attention that recent studies have paid to Victorian fiction and travel literature (for example, Brantlinger, 1988; Franey, 2003), such histories have remained relatively neglected. Therefore, this paper seeks to examine the way that British historians, writing between the Scramble and the eve of the Second World War, represented Africa. It is often asserted that the British enthused about much of Africa’s past. It is claimed that there was an admiration for a simplified, pre-modern existence, in keeping with a Rousseauean conception of the ‘noble savage.’ Some, particularly postcolonialists such as Homi Bhabha, have argued that this all added a sense of disquiet to imperialist proceedings. Bhabha claims that a colonizing power advocates a ‘colonial mimicry’, that is, it wants those it ruled over to become a ‘reformed, recognizable Other, as a subject of difference that is almost the same, but not quite’. -

Recognition of States in International Law

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 53 JUNE, 1944 NUMBER 3 RECOGNITION OF STATES IN INTERNATIONAL LAW By H. LAUTERPACHT I I. INTRODUCTORY Principles of the Recognition of States. To recognize a community as a State is to declare that it fulfills the conditions of statehood as required by international law. If these conditions are present, existing States are under the duty to grant recognition. In the absence of an international organ competent to ascertain and authoritatively to declare the presence of requirements of full international personality, States already estab- lished fulfill that function in their capacity as organs of international law. In thus acting they administer the law of nations. This rule of law signifies that in granting or withholding recognition States do not claim and are not entitled to serve exclusively the interests of their national policy and convenience regardless of the principles of international law in the matter. Although recognition is thus declaratory of an existing fact, such declaration, made in the impartial fulfillment of a legal duty, is constitutive, as between the recognizing State and the new community, of international rights and duties associated with full statehood. Prior to recognition such rights and obligations exist only to the extent to which they have been expressly conceded or legitimately asserted by reference to compelling rules of humanity and justice, either by the existing mem- bers of international society or by the community claiming recognition., These principles are believed to have been accepted by the preponder- ant practice of States. They are also considered to represent rules of con- duct most consistent with the fundamental requirements of international law conceived as a system of law. -

A Report to the Assistant Attorney General, Criminal Division, U.S

Robert Jan Verbelen and the United States Government A Report to the Assistant Attorney General, Criminal Division, U.S. Department of Justice NEAL M. SHER, Director Office of Special Investigations ARON A. GOLBERG, Attorney Office of Special Investigations ELIZABETH B. WHITE, Historian Office of Special Investigations June 16, 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pacre I . Introduction A . Background of Verbelen Investigation ...... 1 B . Scope of Investigation ............. 2 C . Conduct of Investigation ............ 4 I1. Early Life Through World War I1 .......... 7 I11 . War Crimes Trial in Belgium ............ 11 IV . The 430th Counter Intelligence Corps Detachment in Austria ..................... 12 A . Mission. Organization. and Personnel ...... 12 B . Use of Former Nazis and Nazi Collaborators ... 15 V . Verbelen's Versions of His Work for the CIC .... 20 A . Explanation to the 66th CIC Group ....... 20 B . Testimony at War Crimes Trial ......... 21 C . Flemish Interview ............... 23 D . Statement to Austrian Journalist ........ 24 E . Version Told to OSI .............. 26 VI . Verbelen's Employment with the 430th CIC Detachment ..................... 28 A . Work for Harris ................ 28 B . Project Newton ................. 35 C . Change of Alias from Mayer to Schwab ...... 44 D . The CIC Ignores Verbelen's Change of Identity .................... 52 E . Verbelen's Work for the 430th CIC from 1950 to1955 .................... 54 1 . Work for Ekstrom .............. 54 2 . Work for Paulson .............. 55 3 . The 430th CIC Refuses to Conduct Checks on Verbelen and His Informants ....... 56 4 . Work for Giles ............... 60 Verbelen's Employment with the 66th CIC Group ... 62 A . Work for Wood ................. 62 B . Verbelen Reveals His True Identity ....... 63 C . A Western European Intelligence Agency Recruits Verbelen .............. -

Historic Settlements in Denbighshire

CPAT Report No 1257 Historic settlements in Denbighshire THE CLWYD-POWYS ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST CPAT Report No 1257 Historic settlements in Denbighshire R J Silvester, C H R Martin and S E Watson March 2014 Report for Cadw The Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust 41 Broad Street, Welshpool, Powys, SY21 7RR tel (01938) 553670, fax (01938) 552179 www.cpat.org.uk © CPAT 2014 CPAT Report no. 1257 Historic Settlements in Denbighshire, 2014 An introduction............................................................................................................................ 2 A brief overview of Denbighshire’s historic settlements ............................................................ 6 Bettws Gwerfil Goch................................................................................................................... 8 Bodfari....................................................................................................................................... 11 Bryneglwys................................................................................................................................ 14 Carrog (Llansantffraid Glyn Dyfrdwy) .................................................................................... 16 Clocaenog.................................................................................................................................. 19 Corwen ...................................................................................................................................... 22 Cwm ......................................................................................................................................... -

Governing Public Hospitals.Indd

Cover_WHO_nr25_Mise en page 1 17/11/11 15:54 Page1 25 REFORM STRATEGIES AND THE MOVEMENT TOWARDS INSTITUTIONAL AUTONOMY INSTITUTIONAL TOWARDS THE MOVEMENT AND STRATEGIES REFORM GOVERNING PUBLIC HOSPITALS GOVERNING Governing 25 The governance of public hospitals in Europe is changing. Individual hospitals have been given varying degrees of semi-autonomy within the public sector and empowered to make key strategic, financial, and clinical decisions. This study explores the major developments and their implications for national and Public Hospitals European health policy. Observatory The study focuses on hospital-level decision-making and draws together both Studies Series theoretical and practical evidence. It includes an in-depth assessment of eight Reform strategies and the movement different country models of semi-autonomy. towards institutional autonomy The evidence that emerges throws light on the shifting relationships between public-sector decision-making and hospital- level organizational behaviour and will be of real and practical value to those working with this increasingly Edited by important and complex mix of approaches. Richard B. Saltman Antonio Durán The editors Hans F.W. Dubois Richard B. Saltman is Associate Head of Research Policy at the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, and Professor of Health Policy and Management at the Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University in Atlanta. Hans F.W. Dubois Hans F.W. Antonio Durán, Saltman, B. Richard by Edited Antonio Durán has been a senior consultant to the WHO Regional Office for Europe and is Chief Executive Officer of Técnicas de Salud in Seville. Hans F.W. Dubois was Assistant Professor at Kozminski University in Warsaw at the time of writing, and is now Research Officer at Eurofound in Dublin. -

English Society 1660±1832

ENGLISH SOCIETY 1660±1832 Religion, ideology and politics during the ancien regime J. C. D. CLARK published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011±4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de AlarcoÂn 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain # Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published as English Society 1688±1832,1985. Second edition, published as English Society 1660±1832 ®rst published 2000. Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface Baskerville 11/12.5 pt. System 3b2[ce] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Clark, J. C. D. English society, 1660±1832 : religion, ideology, and politics during the ancien regime/J.C.D.Clark. p. cm. Rev. edn of: English society, 1688±1832. 1985. Includes index. isbn 0 521 66180 3 (hbk) ± isbn 0 521 66627 9 (pbk) 1. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 1660±1714. 2. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 18th century. 3. Great Britain ± Politics and government ± 1800±1837. 4. Great Britain ± Social conditions. i.Title. ii.Clark,J.C.D.Englishsociety,1688±1832. -

Palaeoecological, Archaeological and Historical Data and the Making of Devon Landscapes

bs_bs_banner Palaeoecological, archaeological and historical data and the making of Devon landscapes. I. The Blackdown Hills ANTONY G. BROWN, CHARLOTTE HAWKINS, LUCY RYDER, SEAN HAWKEN, FRANCES GRIFFITH AND JACKIE HATTON Brown, A. G., Hawkins, C., Ryder, L., Hawken, S., Griffith, F. & Hatton, J.: Palaeoecological, archaeological and historical data and the making of Devon landscapes. I. The Blackdown Hills. Boreas. 10.1111/bor.12074. ISSN 0300-9483. This paper presents the first systematic study of the vegetation history of a range of low hills in SW England, UK, lying between more researched fenlands and uplands. After the palaeoecological sites were located bespoke archaeological, historical and documentary studies of the surrounding landscape were undertaken specifically to inform palynological interpretation at each site. The region has a distinctive archaeology with late Mesolithic tool scatters, some evidence of early Neolithic agriculture, many Bronze Age funerary monuments and Romano- British iron-working. Historical studies have suggested that the present landscape pattern is largely early Medi- eval. However, the pollen evidence suggests a significantly different Holocene vegetation history in comparison with other areas in lowland England, with evidence of incomplete forest clearance in later-Prehistory (Bronze−Iron Age). Woodland persistence on steep, but poorly drained, slopes, was probably due to the unsuit- ability of these areas for mixed farming. Instead they may have been under woodland management (e.g. coppicing) associated with the iron-working industry. Data from two of the sites also suggest that later Iron Age and Romano-British impact may have been geographically restricted. The documented Medieval land manage- ment that maintained the patchwork of small fields, woods and heathlands had its origins in later Prehistory, but there is also evidence of landscape change in the 6th–9th centuries AD. -

Inventing a French Tyrant: Crisis, Propaganda, and the Origins of Fénelon’S Ideal King

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository INVENTING A FRENCH TYRANT: CRISIS, PROPAGANDA, AND THE ORIGINS OF FÉNELON’S IDEAL KING Kirsten L. Cooper A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Jay M. Smith Chad Bryant Lloyd S. Kramer © 2013 Kirsten L. Cooper ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kirsten L. Cooper: Inventing a French Tyrant: Crisis, Propaganda, and the Origins of Fénelon’s Ideal King (Under the direction of Jay M. Smith and Chad Bryant) In the final decades of the seventeenth century, many voices across Europe vehemently criticized Louis XIV, the most well-known coming from the pen of François Fénelon from within Versailles itself. There were, however, many other critics of varied backgrounds who participated in this common discourse of opposition. From the 1660s to the 1690s the authors of these pamphlets developed a stock of critiques of Louis XIV that eventually coalesced into a negative depiction of his entire style of government. His manner of ruling was rejected as monstrous and tyrannical. Fénelon's ideal king, a benevolent patriarch that he presents as an alternative to Louis XIV, was constructed in opposition to the image of Louis XIV developed and disseminated by these international authors. In this paper I show how all of these authors engaged in a process of borrowing, recopying, and repackaging to create a common critical discourse that had wide distribution, an extensive, transnational audience, and lasting impact for the development of changing ideals of sovereignty. -

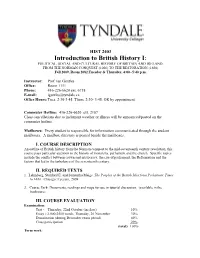

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading.